Diyarbakır

| Diyarbakır | |

|---|---|

| — City — | |

|

|

Diyarbakır

|

|

| Coordinates: | |

| Country | |

| Region | Southeastern Anatolia |

| Province | Diyarbakır |

| Elevation | 675 m (2,215 ft) |

| Population (2007) | |

| - Total | 592,557 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| - Summer (DST) | EEST ([[UTC+3,[1]]]) |

| Postal code | 21x xx |

| Area code(s) | (0090)+ 412 |

| Licence plate | 21 |

| Website | [1] |

Diyarbakır (Ottoman Turkish دیاربکر, Diyâr-ı Bekr; Kurdish ئامهد, Amed; anc. Amida, Aramaic: ܐܡܝܕ, Amid ) is the largest city in southeastern Turkey. Situated on the banks of the River Tigris, it is the administrative capital of the Diyarbakır Province with a population of almost 1.5 million[2]. With a population of about 600,000[2], it is the second largest city in Turkey's South-eastern Anatolia region, after Gaziantep. Within Turkey, Diyarbakır is famed for its culture, folklore, and watermelons. The population of Diyarbakır is made up predominantly of Kurdish people,[1] and the city is sometimes described as the "unofficial capital" of Turkish Kurdistan.[3]

Contents |

Etymology

The most accepted etymology is literal Arabic that translates as the landholdings of the Bekr tribe".[4][5].

History

Antiquity

Amid(a) was the capital of the Aramean kingdom Bet-Zamani from the 13th century B.C. onwards, and later part of the Neo Assyrian Empire . Amid is the name used in the Syriac sources, which also testifies to the fact that it once was the seat of the Church of the East Patriarch and thus an original Assyrian/Syriac stronghold that produced many famous Assyrian theologians and Patriarchs. Some of them found their final resting place in St. Mary Church. There are many relics in the Church, such as the bones of the apostle Thomas and St. Jacob of Sarug (d. 521).

The city was called Amida when the region was under the rule of the Roman (from 66 BC) and the succeeding Byzantine Empires.[6]

From 189 BC to 384 AD, the area to the east and south of present-day Diyarbakır, was ruled by a kingdom known as Corduene.[7]

._caffeeshop_in_diyarbakir.png)

In 359, Shapur II of Persia captured Amida after a siege of 73 days. The Roman soldiers and a large part of the population of the town were massacred by the Persians. The siege is vividly described by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus who was an eyewitness of the event and survived the massacre by escaping from the town.[8]

Armenian historians at one time hypothesized that Diyarbakır was the site of the ancient Armenian city of Tigranakert, (pronounced Dikranagerd in the Western Armenian dialect) and by the nineteenth century the Armenian inhabitants were referring to the city as Dikranagerd. Scholarly research has shown that while the ancient Armenian city was close by, it was not in the same place. The real location of Dikranagerd remains the subject of debate, but Armenians who trace their ancestry to Diyarbakır continue to refer to themselves as "Dikranagerdtsi" (native of Dikranagerd.) The "Dikranagerdtsi's" or Armenians of Diyarbakır were noted for having one of the most unusual dialects of Armenian, one difficult for a speaker of standard Armenian to understand.

The Middle Ages

In 639 the city was captured by the Arab armies of Islam and it remained in Arab hands until the Kurdish dynasty of Marwanid ruled the area during the 10th and 11th centuries. After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the city came under the rule of the Mardin branch of Oghuz Turks and then the Anatolian beylik of Artuklu (circa 1100–1250 in effective terms, although almost a century longer nominally). The whole area was then disputed between the Ilkhanate Turks and Ayyubid Kurdish dynasties for a century, after which it was taken over by the rising Turkmen states of Kara Koyunlu (the Black Sheep) first and Ak Koyunlu (the White Sheep). It was also ruled by Sultanate of Rûm between 1241-1259.

The Ottoman Empire

The city became part of the Ottoman Empire during Sultan Süleyman I's campaign of Irakeyn (the two Iraqs, e.g. Arabian and Persian) in 1534.. The Ottoman eyalet of Diyarbakır corresponded to Turkey's southeastern provinces today, a rectangular area between the Lake Urmia to Palu and from the southern shores of Lake Van to Cizre and the beginnings of the Syrian desert, although its borders saw some changes over time. The city was an important military base for controlling this region and at the same time a thriving city noted for its craftsmen, producing glass and metalwork. For example the doors of Mevlana's tomb in Konya were made in Diyarbakır, as were the gold and silver decorated doors of the tomb of Imam-i Azam in Baghdad.

In the nineteenth century, Diyarbakır prison gained infamy throughout the Ottoman Empire as a site where political prisoners from the enslaved Balkan ethnic groups were sent to serve harsh sentences for speaking or fighting for national freedom.[9]

The 20th century

The 20th century was turbulent for Diyarbakir. During World War I most of the city's Assyrian and Armenian population were murdered at the behest of Diyarbakir's governor Dr. Mehmed Reshid (1873-1919) and the Young Turk regime in what is now known as the Armenian Genocide and Assyrian Genocide.[10][11] Diyarbakir has been described as "an inferno of turture and murder", and the number of Armenians killed there exceeded the city's Armenian population because it was a centre of deportation for all parts of the province. [12] The massacre of Armenians in Diyarbakir was witnessed by Rafael De Nogales[13], who served as an officer in the Ottoman Army. At one time, Diyarbakır had a substantial Armenian and Assyrian population, who comprised almost a third of the city's population. However, almost all were killed during the Armenian Genocide. [14] Few Assyrians and Armenians remain today.

After the surrender of the Ottoman Empire, French troops attempted to occupy the city.

In the three decades following the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923, Diyarbakır became the object of Turkish-nationalist policies against Kurds, as a result of which Kurdish elites were destroyed and many Kurds deported to western Turkey.

The 41-year-old American-Turkish Pirinçlik Air Force Base near Diyarbakır, known as NATO's frontier post for monitoring the former Soviet Union and the Middle East, closed on 30 September 1997. This closure was the result of the general drawdown of US bases in Europe and the improvement in space surveillance technology. The base housed sensitive electronic intelligence-gathering systems that monitored the Middle East, the Caucasus and Russia.

Diyarbakır today

During the recent conflict, the population of the city grew dramatically as villagers from remote areas where fighting was serious left or were forced to leave for the relative security of the city. Rural to urban movement has often been the first step in a migratory pattern that has taken large numbers of Kurds from the east to the west. Diyarbakır grew from 30,000 in the 1930s to 65,000 by 1956, to 140,000 by 1970, to 400,000 by 1990,[15] and eventually swelled to about 1.5 million by 1997.[16] Today the intricate warren of alleyways and old-fashioned tenement blocks that makes up the old city within and around the walls contrasts dramatically with the sprawling suburbs of modern apartment blocks and cheaply-built gecekondu slums to the west.

After the cessation of hostilities between the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) and the Turkish army, a large degree of normality returned to the city, with the Turkish government declaring a end to the 15-year period of emergency rule on 30 November 2002. In August 2005, the Kurdish mayor Osman Baydemir presented the Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan with the following complaints:

- A grant of 500,000 euros from the German Development Fund KFW to redesign the city's waste disposal system was refused by the State Planning Authority (DPT) of the Turkish government in Ankara, and then a 22 million project to renew the system was also prevented.

- A grant of 350,000 euros for the rehabilitation of the Tigris valley, from the Turco-Spanish Economic and Financial Union, was declared unnecessary by the DPT in 2005.

- A dentistry project jointly agreed with and funded by South Korea and EAID (the Eurasian Institute of Dentistry) had to abandoned after the dentists were refused work permits.

- A five million euro project to build a tram system in the city was abandoned after the Turkish government refused to guarantee a 15-year loan from Deutsche Bank that the city had negotiated.

- In the urban renewal project for 2005 presented to the EU commission 10 million euros were granted to Diyarbakır. However the State Planning Authority (DPT)of the Turkish government reallocated 4 million of this to other cities (Gaziantep, Şanlıurfa and Erzurum), which failing to present projects lost this money.

- In another instance a 30 million euro loan from the EU was prevented by the DPT.[17]

According to a November 2006 survey by the Sur Municipality, one of Diyarbakır's metropolitan municipalities, 72% of the inhabitants of the municipality use Kurdish most often in their daily speech, followed by Turkish, and 69% are illiterate in their most widely used vernacular.[18]

Arts and culture

Some jewelry making and other craftwork continues today although the fame of the Diyarbakır's craftsmen has long passed. Folk dancing to the drum and zurna (pipe) are a part of weddings and celebrations in the area.

Cuisine

Diyarbakır is known for rich dishes of lamb (and lamb's liver, kidneys etc.); spices such as black pepper, sumac and coriander; rice, bulgur and butter.

Places of interest

- The city walls - Diyarbakır is surrounded by an almost intact, dramatic set of high walls of black basalt forming a 5.5 km (3.4 mi) circle around the old city. There are four gates into the old city and 82 watch-towers on the walls, which were built in antiquity, restored and extended by the Roman emperor Constantius in 349.

- Places of worship - Diyarbakır boasts numerous medieval mosques and madrassahs including:

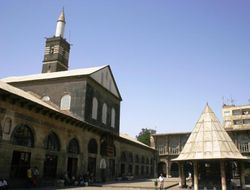

- Ulu Camii ("Great Mosque") built by the Seljuk Turkish Sultan Malik Shah in the 11th century. The mosque, one of the oldest in Turkey, is constructed in alternating bands of black basalt and white limestone. (The same patterning is used in the 16th century Deliler Han Madrassah, which is now a hotel.) The adjoining Mesudiye Medresesi was built at the same time as was another prayer-school in the city Zinciriye Medresesi.

- Hazreti Süleyman Camii - 1155-1169 - Süleyman son of Halid Bin Velid, who died capturing the city from the Arabs, is buried here along with his companions.

- Safa Camii - built in 1532 by the Ak Koyunlu Turkmen tribe.

- Nebii Camii - another Ak Koyunlu mosque, a single-domed stone construction from the 16th century. Nebi Camii means "the mosque of the prophet" and is so-named because of the number of inscriptions in honour of the prophet on its minaret.

- Dört Ayaklı Minare (the four-footed minaret) - built by Kasim Khan of the Akkoyunlu, it is said that one who passes seven times between the four columns will have his wishes granted.

- Fatihpaşa Camii - built in 1520 by Diyarbakır's first Ottoman governor, Bıyıklı Mehmet Paşa ("the moustachioed Mehmet pasha"). The city's earliest Ottoman building it is decorated with fine tilework.

- Hüsrevpaşa Camii - the mosque of the second Ottoman governor, 1512-1528, originally the building was intended to be a school (medrese)

- İskender Paşa Camii - and another mosque of an Ottoman governor, an attractive building in black and white stone, built in 1551.

- Beharampaşa Camii - an Ottoman mosque built in 1572 by the governor of Diyarbakır, Behram Pasha, noted for the well-constructed arches at the entrance.

- Melek Ahmet Camii another 16th century mosque, noted for its tiled prayer-niche, and the double stairway up the minaret.

-

- The Syriac Orthodox Church of Our Lady (Syriac: ܐ ܕܝܠܕܬ ܐܠܗܐ`Idto d-Yoldat Aloho, Turkish: Meryemana kilisesi), was first constructed as a pagan temple in the 1st century BCE. The current construction dates back to the 3rd century, has been restored many times, and is still in use as a place of worship today. There are a number of other churches in the city.

- Museums -

- The Archaeological Museum contains artefacts from the neolithic period, through the Early Bronze Age, Assyrian, Urartu, Roman, Byzantine, Artuklu, Seljuk Turk, Ak Koyunlu, and Ottoman Empire periods.

- Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı Museum - the home of the late poet is a classic example of a traditional Diyarbakır home.

- The birthplace of poet Ziya Gökalp has been preserved as a museum to his life and works.

Notable residents

- Ahmed Arif: Poet

- Aziz Yıldırım: President of Fenerbahçe S.K. sports club

- Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı: Poet

- Cihan Haspolatlı: Galatasaray SK footballer

- Gazi Yaşargil: medical scientist and neurosurgeon

- Hesenê Metê: writer

- Hikmet Çetin: Former Turkish foreign minister, former NATO Senior Civilian Representative in Afghanistan

- Leyla Zana: politician

- Lokman Polat: writer

- Mehmed Emin Bozarslan: writer

- Mehmet Polat: actor

- Naum Faiq: writer

- Osman Baydemir: politician

- Rojen Barnas: writer

- Songül Öden: actress

- Süleyman Nazif: Prominent Young Turk

- Ziya Gökalp: Prominent ideologue of Pan-Turkism and Turanism

- Mıgırdiç Margosyan: writer, some of his books: Gavur Mahallesi, Söyle Margos Nerelisen?, Biletimiz İstanbul'a Kesildi

- Coşkun Sabah: musician

- Emre Baris: Youngest local major of Amnesty International since 2006

- Sayf al-Din al-Amidi: (d. 631/1233 in Damascus), Islamic theologian and legal scholar of the Shafi'i school.

- Ali Haydar Bengi, killed in the Gaza flotilla raid

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Distribution of Kurdish People, GlobalSecurity.org

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.tarsus.bel.tr/tr/about/nufusBilgileri.jsp

- ↑ Gunter, Michael M. (April 2004). "Why Kurdish Statehood is Unlikely". Middle East Policy: 106. "As some have noted, Turkey's road to the EU lies through Diyarbakir (the unofficial capital of Turkish Kurdistan)".

- ↑ Fadhil H. Khudeda / College of Arts/ Dohuk University

- ↑ Turkey - Southeastern Anatolia P 621

- ↑ Theodor Mommsen History of Rome, The Establishment of the Military Monarchy

- ↑ The Seven Great Monarchies Of The Ancient Eastern World, Vol 7

- ↑ The Eye of Command, Kimberly Kagan, p23

- ↑ http://www.archives.government.bg/tda/?cat=183

- ↑ Peter Balakian, The Burning Tigris(New York: Harper Collins Publishing, 2003), 164.

- ↑ David Gaunt, Massacres, Resistance, Protectors (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2006), 295.

- ↑ Walker, Christopher J., "Armenia, The Survival of a Nation", 1980, p227.

- ↑ Taner Akcam, A Shameful Act (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2006), 165.

- ↑ Walker, Christopher J., "Armenia, The Survival of a Nation", 1980, p227.

- ↑ McDowall, David (2004). 3E. ed. A Modern History of the Kurds. IB Tauris. p. 403. ISBN 9781850434160. http://books.google.com/?id=dgDi9qFT41oC&pg=PA403&vq=30,000.

- ↑ Kirişci, Kemal (June 1998). "Turkey". In Janie Hampton. Internally Displaced People: A Global Survey. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd. pp. 198,199.

- ↑ Mavioglu, Ertugrul (2007-09-05). "Baydemir'in raporu: Sekiz büyük proje engellendi" (in Turkish). Radikal. http://www.radikal.com.tr/haber.php?haberno=232040. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ "Belediye Diyarbakırlıyı tanıdı: Kürtçe konuşuyor" (in Turkish). Radikal. Dogan News Agency. 2006-11-24. http://www.radikal.com.tr/haber.php?haberno=205469. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

See also

- Amid (Chaldean Diocese)

External links

- (Turkish) Governorship of Diyarbakır

- (Turkish) Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality

- (Turkish) Diyarbakırspor funs, news, informarmation

- (Turkish) local info

- (Turkish) Information on Diyarbakır

- (Turkish) Diyarbakır news

- (Turkish) Diyarbakır news

- (Turkish) Diyarbakır news

- Pictures of the City

- Diyarbakır Guide and Photo Album, more, more

- Diyarbakır Weather Forecast Information

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||