Benjamin Disraeli

| The Right Honourable The Earl of Beaconsfield KG PC FRS |

|

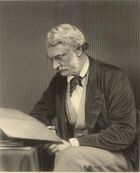

Disraeli in 1878 |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 20 February 1874 – 21 April 1880 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Succeeded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

| In office 27 February 1868 – 1 December 1868 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Succeeded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

|

Leader of the Opposition

|

|

| In office 1 December 1868 – 17 February 1874 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Succeeded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

|

|

|

| In office 6 July 1866 – 29 February 1868 |

|

| Preceded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Succeeded by | George Ward Hunt |

| In office 26 February 1858 – 11 June 1859 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Bt. |

| Succeeded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

| In office 27 February 1852 – 17 December 1852 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles Wood |

| Succeeded by | William Ewart Gladstone |

|

|

|

| Born | 21 December 1804 London, England |

| Died | 19 April 1881 (aged 76) London, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Anne Lewis |

| Religion | Church of England (for most of his life)

Judaism (until age 13) |

| Signature | |

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British Prime Minister, parliamentarian, Conservative statesman and literary figure. He served in government for three decades, twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Although his father had him baptised to Anglicanism at age 13, he was nonetheless the country's first and thus far only Prime Minister who was born Jewish.[1] He played an instrumental role in the creation of the modern Conservative Party after the Corn Laws schism of 1846.

Although a major figure in the protectionist wing of the Conservative Party after 1844, Disraeli's relations with the other leading figures in the party, particularly Lord Derby, the overall leader, were often strained. Not until the 1860s would Derby and Disraeli be on easy terms, and the latter's succession of the former assured. From 1852 onwards, Disraeli's career would also be marked by his often intense rivalry with William Ewart Gladstone, who eventually rose to become leader of the Liberal Party. In this feud, Disraeli was aided by his warm friendship with Queen Victoria, who came to detest Gladstone during the latter's first premiership in the 1870s. In 1876 Disraeli was raised to the peerage as the Earl of Beaconsfield, capping nearly four decades in the House of Commons.

Before and during his political career, Disraeli was well-known as a literary and social figure, although his novels are not generally regarded as a part of the Victorian literary canon. He mainly wrote romances, of which Sybil and Vivian Grey are perhaps the best-known today. He is exceptional among British Prime Ministers for having gained equal social and political renown. He was twice successful as the Glasgow University Conservative Association's candidate for Rector of the University, holding the post for two full terms between 1871 and 1877.

Contents |

Early life

Disraeli's biographers believe he was descended from Italian Sephardic Jews. He claimed Spanish ancestry, possibly referring to the ultimate origin of his family heritage in Spain prior to the expulsion of Jews in 1492, after which many Jews emigrated, in two waves: the bulk to the Ottoman Empire, but many more, first to northern Italy, then to the Netherlands, and finally England.[2]

He was the second child and eldest son of Isaac D'Israeli, a literary critic and historian, and Maria Basevi. Benjamin changed the spelling in the 1820s by dropping the apostrophe.[3] His siblings included Sarah (1802–1859), Naphtali (1807), Ralph (1809–1898), and James (1813–1868).[4] Benjamin at first attended a small school, the Reverend John Potticary's school at Blackheath.[5] His father had Benjamin baptised in 1817 following a dispute with their synagogue. The elder D'Israeli was content to remain outside organized religion. From 1817, Benjamin attended a school at Higham Hill, in Walthamstow, under Eliezer Cogan.[6] His younger brothers, in contrast, attended the superior Winchester College.[7]

His father groomed him for a career in law, and Disraeli was articled to a solicitor in 1821. In 1824, Disraeli toured Belgium and the Rhine Valley with his father and later wrote that it was while travelling on the Rhine that he decided to abandon the law: "I determined when descending those magical waters that I would not be a lawyer."[8] On his return to England he speculated on the stock exchange on various South American mining companies. The recognition of the new South American republics on the recommendation of George Canning had led to a considerable boom, encouraged by various promoters. In this connection, Disraeli became involved with the financier J. D. Powles, one such booster. In the course of 1825, Disraeli wrote three anonymous pamphlets for Powles, promoting the companies.[9]

That same year Disraeli's financial activities brought him into contact with the publisher John Murray who was also involved in the South American mines. Accordingly, they attempted to bring out a newspaper, The Representative, to promote both the cause of the mines and those politicians who supported the mines, specifically George Canning. The paper was a failure, in part because the mining "bubble" burst in late 1825, which ruined Powles and Disraeli. Also, according to Disraeli's biographer, Lord Blake, the paper was "atrociously edited", and would have failed regardless. Disraeli's debts incurred from this debacle would haunt him for the rest of his life.[10]

Before he entered parliament, Disraeli was involved with several women, most notably Henrietta, Lady Sykes (the wife of Sir Francis Sykes, 3rd Bt), who served as the model for Henrietta Temple. It was Henrietta who introduced Disraeli to Lord Lyndhurst, with whom she later became romantically involved. As Lord Blake observed: "The true relationship between the three cannot be determined with certainty ... there can be no doubt that the affair [figurative usage] damaged Disraeli and that it made its contribution, along with many other episodes, to the understandable aura of distrust which hung around his name for so many years."[11]

In 1839 he settled his private life by marrying Mary Anne Lewis, the rich widow of Wyndham Lewis, Disraeli's erstwhile colleague at Maidstone. Mary Lewis was 12 years his senior, and their union was seen as being based on financial interests, but they came to cherish one another.[12]

Literary career

Disraeli turned towards literature after his financial disaster, motivated in part by a desperate need for money, and brought out his first novel, Vivian Grey, in 1826. Disraeli's biographers agree that Vivian Grey was a thinly veiled re-telling of the affair of The Representative, and it proved very popular on its release, although it also caused much offence within the Tory literary world when Disraeli's authorship was discovered. The book, initially anonymous, was purportedly written by a "man of fashion" – someone who moved in high society. Disraeli, then just twenty-three, did not move in high society, and the numerous solecisms present in Vivian Grey made this painfully obvious. Reviewers were sharply critical on these grounds of both the author and the book. Furthermore, John Murray believed that Disraeli had caricatured him and abused his confidence–an accusation denied at the time, and by the official biography, although subsequent biographers (notably Blake) have sided with Murray.[13]

by Sir Francis Grant, 1852

After producing a Vindication of the English Constitution, and some political pamphlets, Disraeli followed up Vivian Grey with a series of novels, The Young Duke (1831), Contarini Fleming (1832), Alroy (1833), Venetia and Henrietta Temple (1837). During the same period he had also written The Revolutionary Epick and three burlesques, Ixion, The Infernal Marriage, and Popanilla. Of these only Henrietta Temple (based on his affair with Henrietta Sykes, wife of Sir Francis William Sykes, 3rd Bt) was a true success.[14]

During the 1840s Disraeli wrote three political novels collectively known as "the Trilogy"–Sybil, Coningsby, and Tancred.[15]

Disraeli's relationships with other male writers of his period were strained or non-existent. After the disaster of The Representative, John Gibson Lockhart became a bitter enemy and the two never reconciled.[16] Disraeli's preference for female company prevented the development of contact with those who were otherwise not alienated by his opinions, comportment or background. One contemporary who tried to bridge the gap, William Makepeace Thackeray, established a tentative cordial relationship in the late 1840s only to see everything collapse when Disraeli took offence at a burlesque of him which Thackeray penned for Punch. Disraeli took revenge in Endymion (published in 1880), when he caricatured Thackeray as "St. Barbe".[17]

Critic William Kuhn argued much of Disraeli's fiction can be read as "the memoirs he never wrote", revealing the inner life of a politician for whom the norms of Victorian public life appeared to represent a social straitjacket – particularly with regard to his allegedly "ambiguous sexuality."[18]

Parliament

Disraeli had been considering a political career as early as 1830, before he departed England for the Mediterranean. His first real efforts, however, did not come until 1832, during the great crisis over the Reform Bill, when he contributed to an anti-Whig pamphlet edited by John Wilson Croker and published by Murray entitled England and France: or a cure for Ministerial Gallomania. The choice of a Tory publication was regarded as odd by Disraeli's friends and relatives, who thought him more of a Radical. Indeed, Disraeli had objected to Murray about Croker inserting "high Tory" sentiment, writing that "it is quite impossible that anything adverse to the general measure of Reform can issue from my pen." Further, at the time Gallomania was published, Disraeli was in fact electioneering in High Wycombe in the Radical interest.[19] Disraeli's politics at the time were influenced both by his rebellious streak and by his desire to make his mark. In the early 1830s the Tories and the interests they represented appeared to be a lost cause. The other great party, the Whigs, was anathema to Disraeli: "Toryism is worn out & I cannot condescend to be a Whig."[20]

Though he initially stood for election, unsuccessfully, as a Radical, Disraeli was a Tory by the time he won a seat in the House of Commons in 1837 representing the constituency of Maidstone.[21]

Although a Conservative, Disraeli was sympathetic to some of the demands of the Chartists and argued for an alliance between the landed aristocracy and the working class against the increasing power of the merchants and new industrialists in the middle class, helping to found the Young England group in 1842 to promote the view that the landed interests should use their power to protect the poor from exploitation by middle-class businessmen. During the twenty years between the Corn Laws and the Second Reform Bill Disraeli would seek a Tory-Radical alliance, to little avail. Prior to the 1867 Reform Bill the working class did not possess the vote and therefore had little tangible political power. Although Disraeli forged a personal friendship with John Bright, a Lancashire manufacturer and leading Radical, Disraeli was unable to convince Bright to sacrifice principle for political gain. After one such attempt, Bright noted in his diary that Disraeli "seems unable to comprehend the morality of our political course."[22]

Protection

Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel passed over Disraeli when putting together his government in 1841 and Disraeli, hurt, gradually became a sharp critic of Peel's government, often deliberately adopting positions contrary to those of his nominal chief.[23] The best known of these cases was the Maynooth grant in 1845 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The end of 1845 and the first months of 1846 were dominated by a battle in parliament between the free traders and the protectionists over the repeal of the Corn Laws, with the latter rallying around Disraeli and Lord George Bentinck. An alliance of pro free-trade Conservatives (the "Peelites"), Radicals, and Whigs carried repeal, and the Conservative Party split: the Peelites moved towards the Whigs, while a "new" Conservative Party formed around the protectionists, led by Disraeli, Bentinck, and Lord Stanley (later Lord Derby).[24]

This split had profound implications for Disraeli's political career: almost every Conservative politician with official experience followed Peel, leaving the rump bereft of leadership. As one biographer wrote, "[Disraeli] found himself almost the only figure on his side capable of putting up the oratorical display essential for a parliamentary leader."[25] Looking on from the House of Lords, the Duke of Argyll wrote that Disraeli "was like a subaltern in a great battle where every superior officer was killed or wounded."[26] If the remainder of the Conservative Party could muster the electoral support necessary to form a government, then Disraeli was now guaranteed high office. However, he would take office with a group of men who possessed little or no official experience, who had rarely felt moved to speak in the House of Commons before, and who, as a group, remained hostile to Disraeli on a personal level, his assault on the Corn Laws notwithstanding.[27]

Bentinck and the leadership

In 1847 a small political crisis occurred which removed Bentinck from the leadership and highlighted Disraeli's differences with his own party. In the preceding general election, Lionel de Rothschild had been returned for the City of London. Ever since Catholic Emancipation, members of parliament were required to swear the oath "on the true faith of a Christian." Rothschild, an unconverted Jew, could not do so and therefore could not take his seat. Lord John Russell, the Whig leader who had succeeded Peel as Prime Minister and like Rothschild a member for the City of London, introduced a Jewish Disabilities Bill to amend the oath and permit Jews to enter Parliament.[28]

Disraeli spoke in favour of the measure, arguing that Christianity was "completed Judaism," and asking of the House of Commons "Where is your Christianity if you do not believe in their Judaism?"[29] While Disraeli did not argue that the Jews did the Christians a favour by killing Christ, as he had in Tancred and would in Lord George Bentinck,[30] his speech was badly received by his own party,[31] which along with the Anglican establishment was hostile to the bill.[32] Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford and a friend of Disraeli's, spoke strongly against the measure and implied that Russell was paying off the Jews for "helping" elect him.[33] Every member of the future protectionist cabinet then in parliament (except Disraeli) voted against the measure. One member who was not, Lord John Manners, stood against Rothschild when the latter re-submitted himself for election in 1849. Bentinck, then still Conservative leader in the Commons, joined Disraeli in speaking and voting for the bill, although his own speech was a standard one of toleration.[34]

In the aftermath of the debate Bentinck resigned the leadership and feuded with Stanley, leader in the Lords and overall leader, who had opposed the measure and directed the party whips—in the Commons—to oppose the measure as well. Bentinck was succeeded by Lord Granby; Disraeli's own speech, thought by many of his own party to be blasphemous, ruled him out for the time being.[35] Even as these intrigues played out, Disraeli was working with the Bentinck family to secure the necessary financing to purchase Hughenden Manor, in Buckinghamshire. This purchase allowed him to stand for the county, which was "essential" if one was to lead the Conservative Party at the time. He and Mary Anne alternated between Hughenden and several homes in London for the remainder of their marriage. These negotiations were complicated by the sudden death of Lord George on 21 September 1848, but Disraeli obtained a loan of £25,000 (equivalent to about £1.96 million as of 2011)[36] from Lord George's brothers Lord Henry Bentinck and Lord Titchfield.[37]

Within a month Granby resigned the leadership in the commons, feeling himself inadequate to the post, and the party functioned without an actual leader in the commons for the remainder of the parliamentary session. At the start of the next session, affairs were handled by a triumvirate of Granby, Disraeli, and John Charles Herries–indicative of the tension between Disraeli and the rest of the party, who needed his talents but mistrusted the man. This confused arrangement ended with Granby's resignation in 1851; Disraeli effectively ignored the two men regardless.[38]

Office

First Derby government

The first opportunity for the protectionist Tories under Disraeli and Stanley to take office came in 1851, when Lord John Russell's government was defeated in the House of Commons over the Ecclesiastical Titles Act 1851. Disraeli was to have been Home Secretary, with Stanley (becoming the Earl of Derby later that year) as Prime Minister. Other possible ministers included Sir Robert Inglis, Henry Goulburn, John Charles Herries, and Lord Ellenborough. The Peelites, however, refused to serve under Stanley or with Disraeli so long as the question of free trade remained unsettled, and attempts to form a purely protectionist government failed. Derby supposedly remarked at the time, "Pshaw! These are not names which I can put before the Queen!"[39]

Russell resumed office, but resigned again in early 1852 when a combination of the protectionists and Lord Palmerston defeated him on a Militia Bill.[40] This time Lord Derby (as he had become) took office, and to general surprise appointed Disraeli Chancellor of the Exchequer.[41] Disraeli had offered to stand aside as leader in the House of Commons in favour of Palmerston, but the latter declined.[42]

The primary responsibility of a mid-Victorian chancellor was to produce a Budget for the coming fiscal year. Disraeli proposed to reduce taxes on malt and tea (indirect taxation); additional revenue would come from an increase in the house tax. More controversially, Disraeli also proposed to alter the workings of the income tax (direct taxation) by "differentiating"–i.e., different rates would be levied on different types of income.[43] The establishment of the income tax on a permanent basis had been the subject of much inter-party discussion since the fall of Peel's ministry, but no consensus had been reached, and Disraeli was criticised for mixing up details over the different "schedules" of income. Disraeli's proposal to extend the tax to Ireland gained him further enemies, and he was also hampered by an unexpected increase in defence expenditure, which was forced on him by Derby and Sir John Pakington (Secretary of State for War and the Colonies) (leading to his celebrated remark to John Bright about the "damned defences").[44] This, combined with bad timing and perceived inexperience led to the failure of the Budget and consequently the fall of the government in December of that year.[45]

Gladstone's final speech on the failed Budget marked the beginning of over twenty years of mutual parliamentary hostility, as well as the end of Gladstone's formal association with the Conservative Party. No Conservative reconciliation remained possible so long as Disraeli remained leader in the House of Commons.[46]

Opposition

With the fall of the government, Disraeli and the Conservatives returned to the opposition benches. Derby's successor as Prime Minister was the Peelite Lord Aberdeen, whose ministry was composed of both Peelites and Whigs. Disraeli himself was succeeded as chancellor by Gladstone.[47]

Second Derby government

Lord Palmerston's government collapsed in 1858 amid public fallout over the Orsini affair and Derby took office at the head of a purely 'Conservative' administration. He again offered a place to Gladstone, who declined. Disraeli remained leader of the House of Commons and returned to the Exchequer. As in 1852 Derby's was a minority government, dependent on the division of its opponents for survival.[48] The principal measure of the 1858 session would be a bill to re-organise governance of India, the Indian Mutiny having exposed the inadequacy of dual control. The first attempt at legislation was drafted by the President of the Board of Control, Lord Ellenborough, who had previously served as Governor-General of India (1841–44). The bill, however, was riddled with complexities and had to be withdrawn. Soon after, Ellenborough was forced to resign over an entirely separate matter involving the current Governor-General, Lord Canning.[49]

Faced with a vacancy, Disraeli and Derby tried yet again to bring Gladstone into the government. Disraeli wrote a personal letter to Gladstone, asking him to place the good of the party above personal animosity: "Every man performs his office, and there is a Power, greater than ourselves, that disposes of all this..." In responding to Disraeli Gladstone denied that personal feelings played any role in his decision then and previously to accept office, while acknowledging that there were differences between him and Derby "broader than you may have supposed." Gladstone also hinted at the strength of his own faith, and the role it played in his public life, when he addressed Disraeli's most personal and private appeal:

I state these points fearlessly and without reserve, for you have yourself well reminded me that there is a Power beyond us that disposes of what we are and do, and I find the limits of choice in public life to be very narrow.—W. E. Gladstone to Disraeli, 1858[50]

With Gladstone's refusal Derby and Disraeli looked elsewhere and settled on Disraeli's old friend Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who became Secretary of State for the Colonies; Derby's son Lord Stanley, succeeded Ellenborough at the Board of Control. Stanley, with Disraeli's assistance, proposed and guided through the house the India Act, under which the subcontinent would be governed for sixty years. The East India Company and its Governor-General were replaced by a viceroy and the Indian Council, while at Westminster the Board of Control was abolished and its functions assumed by the newly created India Office, under the Secretary of State for India.[51]

The 1867 Reform Bill

Four-time Prime Minister

After engineering the defeat of a Liberal Reform Bill introduced by Gladstone in 1866,[52] Disraeli and Derby introduced their own measure in 1867.[53] This was primarily a political strategy designed to give the Conservative party control of the reform process and the subsequent long-term benefits in the Commons, similar to those derived by the Whigs after their 1832 Reform Act. It was thought that if the Conservatives were able to secure this piece of legislation, then the newly enfranchised electorate may return their gratitude to the Tories in the form of a Conservative vote at the next general election. As a result, this would give the Conservatives a greater chance of forming a majority government. After so many years in the 'stagnant backwaters' of British politics, this seemed most appealing. The Reform Act 1867 extended the franchise by 938,427 – an increase of 88% – by giving the vote to male householders and male lodgers paying at least 10 pounds for rooms and eliminating rotten boroughs with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, and granting constituencies to fifteen unrepresented towns, and extra representation in parliament to larger towns such as Liverpool and Manchester, which had previously been under-represented in Parliament.[54] This act was unpopular with the right wing of the Conservative Party, most notably Lord Cranborne (later the Marquess of Salisbury), who resigned from the government and spoke against the bill, accusing Disraeli of "a political betrayal which has no parallel in our Parliamentary annals."[55] Cranborne, however, was unable to lead a rebellion similar to that which Disraeli had led against Peel twenty years earlier.[56]

Prime minister

First government

Derby's health had been declining for some time and he finally resigned as Prime Minister in late February 1868; he would live for twenty months. Disraeli's efforts over the past two years had dispelled, for the time being, any doubts about him succeeding Derby as leader of the Conservative Party and therefore Prime Minister. As Disraeli remarked, "I have climbed to the top of the greasy pole."[57]

However, the Conservatives were still a minority in the House of Commons, and the passage of the Reform Bill required the calling of new election once the new voting register had been compiled. Disraeli's term as Prime Minister would therefore be fairly short, unless the Conservatives won the general election. He made only two major changes in the cabinet: he replaced Lord Chelmsford as Lord Chancellor with Lord Cairns, and brought in George Ward Hunt as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Disraeli and Chelmsford had never got along particularly well, and Cairns, in Disraeli's view, was a far stronger minister.[58]

Disraeli's first premiership was dominated by the heated debate over the established Church of Ireland. Although Ireland was overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, the Protestant Church remained the established church and was funded by direct taxation. An initial attempt by Disraeli to negotiate with Cardinal Manning the establishment of a Roman Catholic university in Dublin foundered in March when Gladstone moved resolutions to disestablish the Irish Church altogether. The proposal divided the Conservative Party while reuniting the Liberals under Gladstone's leadership. While Disraeli's government survived until the December general election, the initiative had passed to the Liberals, who were returned to power with a majority of 170.[59]

Second government

After six years in opposition, Disraeli and the Conservative Party won the election of 1874, giving the party its first absolute majority in the House of Commons since the 1840s. Under the stewardship of R. A. Cross, the Home Secretary, Disraeli's government introduced various reforms, including the Artisan's and Labourers' Dwellings Improvement Act 1875, the Public Health Act 1875, the Sale of Food and Drugs Act (1875), and the Education Act (1876). His government also introduced a new Factory Act meant to protect workers, the Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act 1875 to allow peaceful picketing, and the Employers and Workmen Act (1875) to enable workers to sue employers in the civil courts if they broke legal contracts. As a result of these social reforms the Liberal-Labour MP Alexander Macdonald told his constituents in 1879, "The Conservative party have done more for the working classes in five years than the Liberals have in fifty."[60]

Imperialism

Disraeli cultivated a public image of himself as an Imperialist with grand gestures such as conferring on Queen Victoria the title “Empress of India”.

Disraeli was, according to some interpretations, a supporter of the expansion and preservation of the British Empire in the Middle East and Central Asia. In spite of the objections of his own cabinet and without Parliament's consent, he obtained a short-term loan from Lionel de Rothschild in order to purchase 44% of the shares of the Suez Canal Company. Before this action, though, he had for the most part opted to continue the Whig policy of limited expansion, preferring to maintain the then-current borders as opposed to promoting expansion.[61]

Disraeli and Gladstone clashed over Britain's Balkan policy. Disraeli saw the situation as a matter of British imperial and strategic interests, keeping to Palmerston's policy of supporting the Ottoman Empire against Russian expansion. According to Blake, Disraeli believed in upholding Britain's greatness through a tough, "no nonsense" foreign policy that put Britain's interests above the "moral law" that advocated emancipation of small nations.[62] Gladstone, however, saw the issue in moral terms, for Bulgarian Christians had been massacred by the Turks and Gladstone therefore believed it was immoral to support the Ottoman Empire. Blake further argued that Disraeli's imperialism "decisively orientated the Conservative party for many years to come, and the tradition which he started was probably a bigger electoral asset in winning working-class support during the last quarter of the century than anything else".[62]

A leading proponent of the Great Game, Disraeli introduced the Royal Titles Act 1876, which created Queen Victoria Empress of India, putting her at the same level as the Russian Tsar. In his private correspondence with the Queen, he proposed "to clear Central Asia of Muscovites and drive them into the Caspian".[63] In order to contain Russia's influence, he launched an invasion of Afghanistan and signed the Cyprus Convention with Turkey, whereby this strategically placed island was handed over to Britain.

Disraeli scored another diplomatic success at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, in preventing Bulgaria from gaining full independence, limiting the growing influence of Russia in the Balkans and breaking up the League of the Three Emperors.[64] However, difficulties in South Africa (epitomised by the defeat of the British Army at the Battle of Isandlwana), as well as Afghanistan, weakened his government and led to his party's defeat in the 1880 election.[65]

Title and death

Disraeli was elevated to the House of Lords in 1876 when Queen Victoria made him Earl of Beaconsfield and Viscount Hughenden.[66]

In the general election of 1880 Disraeli's Conservatives were defeated by Gladstone's Liberals, in large part owing to the uneven course of the Second Anglo-Afghan War. The Irish Home Rule vote in England contributed to his party's defeat. Disraeli became ill soon after and died in April 1881.[67]

He is buried in a vault beneath St Michael's Church in the grounds of his home Hughenden Manor, accessed from the churchyard. Against the outside wall of the church is a memorial erected in his honour by Queen Victoria. His literary executor, and for all intents and purposes his heir, was his private secretary, Lord Rowton.[68] The Disraeli vault also contains the body of Sarah Brydges Willyams, the wife of James Brydges Willyams of St Mawgan in Cornwall. Her wish to be buried there was granted after she left an estate sworn at under £40,000, of which Disraeli received over £30,000.

Disraeli also has a memorial in Westminster Abbey.

Judaism

Although born of Jewish parents, Disraeli was baptised in the Christian faith at the age of thirteen, and remained an observant Anglican for the rest of his life.[69] At the same time, he was ethnically Jewish and believed the two positions to be compatible, as well as seeing no conflict of interest in using British power to support Jewish interests (such as supporting the tolerant Ottoman Empire above the anti-Semitic Tsarist Empire). Adam Kirsch, in his biography of Disraeli, states that his Jewishness was "both the greatest obstacle to his ambition and its greatest engine."[70] Much of the criticism of his policies was couched in anti-Semitic terms. He was depicted in some antisemitic political cartoons with a big nose and curly black hair, called "Shylock" and "abominable Jew," and portrayed in the act of ritually murdering the infant Britannia.[70] In response to an anti-Semitic comment in the British parliament, Disraeli memorably defended his Jewishness with the statement, "Yes, I am a Jew, and when the ancestors of the Right Honourable Gentleman were brutal savages in an unknown island, mine were priests in the Temple of Solomon."[71] A likely apocryphal story states that Disraeli reconverted to Judaism on his deathbed.[72]

Disraeli's governments

- First Disraeli ministry (February–December 1868)

- Second Disraeli ministry (February 1874–April 1880)

Works by Disraeli

Fiction

- Vivian Grey (1826; Vivian Grey at Project Gutenberg)

- Popanilla (1828; Popanilla at Project Gutenberg)

- The Young Duke (1831)

- Contarini Fleming (1832)

- Alroy (1833)

- The Infernal Marriage (1834)

- Ixion in Heaven (1834)

- The Revolutionary Epick (1834)

- The Rise of Iskander (1834; The Rise of Iskander at Project Gutenberg)

- Henrietta Temple (1837)

- Venetia (1837; Venetia at Project Gutenberg)

- The Tragedy of Count Alarcos (1839); The Tragedy of Count Alarcos at Project Gutenberg)

- Coningsby, or the New Generation (1844; Coningsby at Project Gutenberg)

- Sybil, or The Two Nations (1845; Sybil or, The Two Nations at Project Gutenberg)

- Tancred, or the New Crusade (1847; Tancred at Project Gutenberg)

- Lothair (1870; Lothair at Project Gutenberg)

- Endymion (1880; Endymion at Project Gutenberg)

- Falconet (book) (unfinished 1881)

Non-fiction

- An Inquiry into the Plans, Progress, and Policy of the American Mining Companies (1825)

- Lawyers and Legislators: or, Notes, on the American Mining Companies (1825)

- The present state of Mexico (1825)

- England and France, or a Cure for the Ministerial Gallomania (1832)

- What Is He? (1833)

- The Vindication of the English Constitution (1835)

- The Letters of Runnymede (1836)

- Lord George Bentinck (1852)

References

- ↑ "Benjamin Disraeli". Number10.gov.uk. http://www.number10.gov.uk/history-and-tour/prime-ministers-in-history/benjamin-disraeli. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 3. Norman Gash, reviewing Blake's work, argued that Benjamin's claim to Spanish ancestry could not be entirely dismissed. (Gash 1968)

- ↑ Opponents, however, continued to include the apostrophe in correspondence. Lord Lincoln, writing to Sir Robert Peel in 1846, referred to "D'Israeli." (Conancher 1958, p. 435). Peel did so as well, see Gash 1972, p. 387. Even in the 1870s, towards the end of Disraeli's career, this practice continued. See Wohl 1995, p. 381, ff. 22.

- ↑ Rhind 1993, p. I, 3

- ↑ Rhind 1993, p. I, 157

- ↑

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900. London: Smith, Elder & Co. - ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 22

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 24–26; Veliz 1975, pp. 637–663

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 116–119

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 158

- ↑ Graubard 1967, p. 139

- ↑ For Blake's account of Henrietta Sykes, see Blake 1966, pp. 94–119.

- ↑ Blake, pp. 190-191.

- ↑ Cline 1941

- ↑ Cline 1943. This view has been accepted by most historians. See Merritt 1968, who argues that St. Barbe was an attack on Thomas Carlyle.

- ↑ Dugdale, John (5 May 2007). "Review of 'The Politics of Pleasure: A Portrait of Benjamin Disraeli', by William Kuhn". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2007/may/05/featuresreviews.guardianreview26. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 84–86

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 87

- ↑ Blake, p. 85.

- ↑ Trevelyan 1913, p. 207. The specific occasion was the 1852 Budget. Disraeli seems to have held out the possibility of Bright, Richard Cobden, and Thomas Milner Gibson eventually joining the cabinet in exchange for the support of the Radicals.

- ↑ Peel's reasons for doing so are disputed. Some historians suggest Edward Stanley's well-known antipathy to Disraeli as the prime factor. Robert Blake dismisses these claims, arguing instead that Peel's need to balance the various factions of the Conservative Party, and the heavy preponderance of aristocrats within the cabinet, precluded Disraeli's inclusion. See Cline 1939, and Blake 1966, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ For the bitterness over the Corn Laws, see Blake 1966, pp. 228–234. For the effect of the split, see Blake 1966, pp. 241–243.

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 247

- ↑ Quoted in Blake 1966, pp. 247–248

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 260

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 258

- ↑ Hansard, 3rd Series, xcv, 1321-1330, 16 December 1847.

- ↑ Disraeli, Benjamin (1852). Lord George Bentinck: A Political Biography (2nd ed.). Colburn and Co.. pp. 488–489. doi:10.1007/b62130. ISBN 354063293X.

- ↑ On the other hand, both Russell and Gladstone thought it was brave for Disraeli to speak as he did. Morley, 715-716.

- ↑ Of the 26 Anglican bishops and archbishops who sat in the House of Lords, 23 voted on the measure altogether, and 17 were opposed.

- ↑ Hansard, 3rd Series, xcviii, 1374-1378, 25 May 1848.

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 259–260

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 261–262

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Measuring Worth: UK CPI.

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 251–254

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 266–269

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 301–305

- ↑ Palmerston got his "tit for tat" with "Johnny Russell", who under pressure from the Crown had dismissed Palmerston from the Foreign Office the previous December.

- ↑ The expectation had been that Disraeli would assume the Foreign or Home offices.

- ↑ Blake, p. 311.

- ↑ Ghosh 1984, pp. 269–273; Matthew 1986, p. 621.

- ↑ Bright's diary quotes the conversation in full. See Trevelyan 1913, pp. 205–206

- ↑ On the centrality of the income tax, see Matthew 1986, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Blake, pp. 346-347.

- ↑ Blake, p. 350.

- ↑ Hawkins 1984

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 379–382

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 382–384

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 385–386

- ↑ Blake, pp. 442-444.

- ↑ Blake, pp. 456-457.

- ↑ Conancher 1971, p. 177

- ↑ Quoted in Blake 1966, p. 473

- ↑ Blake, p. 461..

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 485–487

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 487–489

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 496–502

- ↑ Monypenny & Buckle 1929, p. 709

- ↑ For the Suez deal, see Blake 1966, pp. 581–587.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Blake 1966, p. 760

- ↑ Quoted from Disraeli's letter to the Queen in Mahajan, 53.

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 649–654

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 660–679

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 566

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 749

- ↑ Blake 1966, pp. 751–756

- ↑ Blake 1966, p. 11. See also Endelman 1985, p. 115.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Julius, Anthony (23 January 2009). "Judaism's Redefiner". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/25/books/review/Julius-t.html?ref=books. Retrieved 18 September 2009

- ↑ "The Lost Art of the Insult". Time. 6 July 2003. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,463071,00.html. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ↑ Ragussis, M. (2004). Disraeli's Jewishness, and: Benjamin Disraeli: The Fabricated Jew in Myth and Memory (review). Victorian Studies,46(2), pg. 333-335.

Bibliography

- Blake, Robert (1966). Disraeli. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Carter, Nick (June 1997). "Hudson, Malmesbury and Cavour: British Diplomacy and the Italian Question, February 1858 to June 1859". The Historical journal 40 (2): 389–413. doi:10.1017/S0018246X97007218.

- Cline, C.L. (February 1941). "Disraeli and John Gibson Lockhart". Modern Language Notes (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 56 (2): 134–137. doi:10.2307/2911518. http://jstor.org/stable/2911518.

- Cline, C.L. (December 1939). "Disraeli and Peel's 1841 Cabinet". The Journal of Modern History 11 (4): 509–512. doi:10.1086/236397.

- Cline, C.L. (October 1943). "Disraeli and Thackeray". The Review of English Studies 19 (76): 404–408. doi:10.1093/res/os-XIX.76.404.

- Conancher, J.B. (1971). The Emergence of British Parliamentary Democracy in the Nineteenth Century. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Conancher, J.B. (July 1958). "Peel and the Peelites, 1846–1850". The English Historical Review 73 (288): 431–452. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXIII.288.431.

- Endelman, Todd M. (May 1985). "Disraeli's Jewishness Reconsidered". Modern Judaism 5 (2): 109–123. doi:10.1093/mj/5.2.109.

- Gash, Norman (April 1968). "Review of Disraeli, by Robert Blake". The English Historical Review 83 (327): 360–364. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXIII.CCCXXVII.360.

- Gash, Norman (1972). Sir Robert Peel: The Life of Sir Robert Peel after 1830. Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0-87471-132-0.

- Ghosh, P.R. (April 1984). "Disraelian Conservatism: A Financial Approach". The English Historical Review 99 (391): 268–296. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIX.CCCXCI.268.

- Graubard, Stephen R.; Blake, Robert (October 1967). "Review of Disraeli, by Robert Blake". The American Historical Review (American Historical Association) 73 (1): 139. doi:10.2307/1849087. http://jstor.org/stable/1849087.

- Hawkins, Angus (Spring 1984). "British Parliamentary Party Alignment and the Indian Issue, 1857–1858". The Journal of British Studies 23 (2): 79–105. doi:10.1086/385819.

- Jerman, B.R.. The Young Disraeli. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kidd, Joseph (1889). "The Last Illness of Lord Beaconsfield". The Nineteenth Century: A Monthly Review 26.

- Kirsch, Adam. Benjamin Disraeli. New York: Schocken.

- Mahajan, Sneh (2002). British Foreign Policy, 1874-1914. Routledge. ISBN 0415260108.

- Matthew, H.C.G. (September 1979). "Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Politics of Mid-Victorian Budgets". The Historical journal 22 (3): 615–643. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00017015.

- Matthew, H.C.G. (1986). Gladstone, 1809-1874. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198229097.

- Merritt, James D. (June 1968). "The Novelist St. Barbe in Disraeli's Endymion: Revenge on Whom?". Nineteenth-Century Fiction 23 (1): 85–88. doi:10.1525/ncl.1968.23.1.99p0201m.

- Monypenny, William Flavelle; Buckle, George Earle (1929). The Life of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield. Volume II. 1860–1881. London: John Murray.

- Morley, John (1922). The life of William Ewart Gladstone, volume 2. London: Macmillan. http://books.google.com/?id=gD0GAQAAIAAJ.

- Parry, J.P. (September 2000). "Disraeli and England". The Historical journal 43 (3): 699–728. doi:10.1017/S0018246X99001326.

- Rhind, Neil (1993). Blackheath village and environs. London: Bookshop Blackheath. ISBN 0950513652.

- Seton-Watson, R.W. (1972). Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern Question. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Trevelyan, G.M. (1913). The Life of John Bright. London: Constable.

- Veliz, Claudio (November 1975). "Egana, Lambert, and the Chilean Mining Associations of 1825". The Hispanic American Historical Review (Duke University Press) 55 (4): 637–663. doi:10.2307/2511948. http://jstor.org/stable/2511948.

- Winter, James (January 1966). "The Cave of Adullam and Parliamentary Reform". The English Historical Review 81 (318): 38–55. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXI.CCCXVIII.38.

- Wohl, Anthony S. (July 1995). ""Dizzi-Ben-Dizzi": Disraeli as Alien". The Journal of British Studies 34 (3): 375–411. doi:10.1086/386083.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Benjamin Disraeli

- Works by Benjamin Disraeli at Project Gutenberg

- Benjamin Disraeli Quotes

- Disraeli as the inventor of modern conservatism at The Weekly Standard

- More about Benjamin Disraeli on the Downing Street website.

- BBC Radio 4 series The Prime Ministers

- Hughenden Manor information at the National Trust

- Bodleian Library Disraeli bicentenary exhibition, 2004

- What Disraeli Can Teach Us by Geoffrey Wheatcroft from The New York Review of Books

- Another version of the same text at PowellsBooks.blog

- Archival material relating to Benjamin Disraeli listed at the UK National Register of Archives

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Charles Wood, Bt |

Chancellor of the Exchequer 1852 |

Succeeded by William Ewart Gladstone |

| Preceded by Lord John Russell |

Leader of the House of Commons 1852 |

Succeeded by Lord John Russell |

| Preceded by Sir George Lewis, Bt |

Chancellor of the Exchequer 1858–1859 |

Succeeded by William Ewart Gladstone |

| Preceded by The Viscount Palmerston |

Leader of the House of Commons 1858–1859 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Palmerston |

| Preceded by William Ewart Gladstone |

Chancellor of the Exchequer 1866–1868 |

Succeeded by George Ward Hunt |

| Leader of the House of Commons 1866–1868 |

Succeeded by William Ewart Gladstone |

|

| Preceded by The Earl of Derby |

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 1868 |

|

| Preceded by William Ewart Gladstone |

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 1874–1880 |

|

| Leader of the House of Commons 1874–1876 |

Succeeded by Sir Stafford Northcote, Bt |

|

| Preceded by The Earl of Malmesbury |

Lord Privy Seal 1876–1878 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Northumberland |

| Preceded by The Duke of Richmond |

Leader of the House of Lords 1876–1880 |

Succeeded by The Earl Granville |

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

| Preceded by Abraham Wildey Robarts Wyndham Lewis |

Member of Parliament for Maidstone 1837–1841 With: Wyndham Lewis 1837–1838 John Minet Fector 1838–1841 |

Succeeded by Alexander Beresford-Hope George Dodd |

| Preceded by Richard Jenkins Robert Aglionby Slaney |

Member of Parliament for Shrewsbury 1841–1847 With: George Tomline |

Succeeded by Edward Holmes Baldock Robert Aglionby Slaney |

| Preceded by Caledon Du Pre William Fitzmaurice Christopher Tower |

Member of Parliament for Buckinghamshire 1847–1876 With: Caledon Du Pre 1847–1874 The Hon. Charles Cavendish 1847–1857 The Hon. William Cavendish 1857–1863 Sir Robert Bateson Harvey 1863–1868, 1874–1876 Nathaniel Lambert 1868–1876 |

Succeeded by Sir Robert Bateson Harvey Nathaniel Lambert Thomas Fremantle |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Marquess of Granby |

Conservative Leader in the Commons 1849–1876 with Marquess of Granby John Charles Herries (1849–1851) |

Succeeded by Sir Stafford Northcote, Bt |

| Preceded by The Earl of Derby |

Leader of the British Conservative Party 1868–1881 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Salisbury |

| Preceded by The Duke of Richmond |

Leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Lords 1876–1881 |

|

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Derby |

Rector of the University of Glasgow 1871–1877 |

Succeeded by William Ewart Gladstone |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Earl of Beaconsfield 1876–1881 |

Extinct |

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)