Didgeridoo

Top: Traditionally crafted & decorated Middle: Bamboo souvenir didgeridoo Bottom: Traditionally crafted & undecorated |

|

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification |

|

| Hornbostel-Sachs classification | (Aerophone sounded by lip movement) |

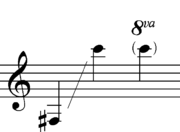

| Playing range | |

Written range:

|

|

| Related instruments | |

| Trumpet, Flugelhorn, Cornet, Bugle, Natural trumpet, Post horn, Roman tuba, Bucina, Shofar, Conch, Lur, Baritone horn, Bronze Age Irish Horn |

|

The didgeridoo (also known as a didjeridu or didge) is a wind instrument developed by Indigenous Australians of northern Australia at least 1,500 years ago and is still in widespread usage today both in Australia and around the world. It is sometimes described as a natural wooden trumpet or "drone pipe". Musicologists classify it as a brass aerophone.[1]

There are no reliable sources stating the didgeridoo's exact age. Archaeological studies of rock art in Northern Australia suggest that the Aboriginal people of the Kakadu region of the Northern Territory have been using the didgeridoo for at least 1,500 years, based on the dating of paintings on cave walls and shelters from this period. A clear rock painting in Ginga Wardelirrhmeng, on the northern edge of the Arnhem Land plateau, from the freshwater period[2] shows a didgeridoo player and two songmen participating in an Ubarr Ceremony.[3]

A modern didgeridoo is usually cylindrical or conical, and can measure anywhere from 1 to 3 m (3 to 10 ft) long. Most are around 1.2 m (4 ft) long. The length is directly related to the 1/2 sound wavelength of the keynote. Generally, the longer the instrument, the lower the pitch or key of the instrument.

Contents |

Etymology

"Didgeridoo" is considered to be an onomatopoetic word of Western invention. It has also been suggested that it may be derived from the Irish words dúdaire or dúidire, meaning variously 'trumpeter; constant smoker, puffer; long-necked person, eavesdropper; hummer, crooner' and dubh, meaning "black" (or duth, meaning "native").[4] However, this theory is not widely accepted.

The earliest occurrences of the word in print include a 1919 issue of Smith's Weekly where it was referred to as an "infernal didjerry" which "produced but one sound - (phonic) didjerry, didjerry, didjerry and so on ad infinitum", the 1919 Australian National Dictionary, The Bulletin in 1924 and the writings of Herbert Basedow in 1926. There are numerous names for this instrument among the Aboriginal people of northern Australia, with yirdaki one of the better known words in modern Western society. Yirdaki, also sometimes spelt yidaki, refers to the specific type of instrument made and used by the Yolngu people of north-east Arnhem Land. Many believe that it is a matter of etiquette to reserve tribal names for tribal instruments, though retailers and businesses have been quick to exploit these special names for generic tourist-oriented instruments.

Regional names for the didgeridoo

There are at least 45 different synonyms for the didgeridoo. The following are some of the more common regional names.[5]

| Tribal Group | Region | Local Name |

|---|---|---|

| Anindilyakwa | Groote Eylandt | ngarrriralkpwina |

| Yolngu | Arnhem Land | yirdaki |

| Gupapuygu | Arnhem Land | Yiraka |

| Djinang | Arnhem Land | Yirtakki |

| Iwaidja | Cobourg Peninsula | Wuyimba/ buyigi |

| Jawoyn | Katherine | artawirr |

| Gagudju | Kakadu | garnbak |

| Lardil | Mornington Island | djibolu |

| Ngarluma | Roebourne, W.A. | Kurmur |

| Nyul Nyul | Kimberleys | ngaribi |

| Warray | Adelaide River | bambu |

| Mayali | Alligator River | martba |

| Pintupi | Central Australia | paampu |

| Arrernte | Alice Springs | Ilpirra |

Construction and play

See also: Modern didgeridoo designs

Authentic Aboriginal didgeridoos are produced in traditionally-oriented communities in Northern Australia or by makers who travel to Central and Northern Australia to collect the raw materials. They are usually made from hardwoods, especially the various eucalyptus species that are endemic to the region.[6] Sometimes a native bamboo, such as Bambusa arnhemica, or pandanus is used. Generally the main trunk of the tree is harvested, though a substantial branch may be used instead. Aboriginal didgeridoo craftsmen spend considerable time in the challenging search for a tree that has been hollowed out by termites to just the right degree. If the hollow is too big or too small, it will make a poor quality instrument.

When a suitable tree is found and cut down, the segment of trunk or branch that will be made into a didgeridoo is cut out. The bark is taken off, the ends trimmed, and some shaping of the exterior then results in a finished instrument. This instrument may be painted or left undecorated. A rim of beeswax may be applied to the mouthpiece end. Traditional instruments made by Aboriginal craftsmen in Arnhem Land are sometimes fitted with a 'sugarbag' mouthpiece. This black beeswax comes from wild bees and has a distinctive aroma.

Non-traditional didgeridoos can also be made from PVC piping, non-native hard woods (typically split, hollowed and rejoined), fiberglass, metal, agave, clay, hemp (a bioplastic named zelfo), and even carbon fiber. These didges typically have an upper inside diameter of around 1.25" down to a bell end of anywhere between two to eight inches and have a length corresponding to the desired key. The mouthpiece can be constructed of beeswax, hardwood or simply sanded and sized by the craftsman. In PVC, an appropriately sized rubber stopper with a hole cut into it is equally acceptable, or to finely sand and buff the end of the pipe to create a comfortable mouthpiece.

Modern didgeridoo designs are distinct from the traditional Australian Aboriginal didgeridoo, and are innovations recognized by musicologists.[7][8] Didgeridoo design innovation started in the late 20th Century using non-traditional materials and non-traditional shapes.

The didgeridoo is played with continuously vibrating lips to produce the drone while using a special breathing technique called circular breathing. This requires breathing in through the nose whilst simultaneously expelling stored air out of the mouth using the tongue and cheeks. By use of this technique, a skilled player can replenish the air in their lungs, and with practice can sustain a note for as long as desired. Recordings exist of modern didgeridoo players playing continuously for more than 40 minutes; Mark Atkins on Didgeridoo Concerto (1994) plays for over 50 minutes continuously.

Fellow of the British Society Anthony Baines wrote that the didgeridoo functions "...as an aural kaleidoscope of timbres"[9] and that "the extremely difficult virtuoso techniques developed by expert performers find no parallel elsewhere."[9]

Decoration

Many didgeridoos are painted using traditional or modern paints by either their maker or a dedicated artist, however it is not essential that the instrument be decorated. It is also common to retain the natural wood grain with minimal or no decoration. Some modern makers deliberately avoid decoration if they are not of Indigenous Australian descent, or leave the instrument blank for an Indigenous Australian artist to decorate it at a later stage.

Physics and operation

A termite-bored didgeridoo has an irregular shape that, overall, usually increases in diameter towards the lower end. This shape means that its resonances occur at frequencies that are not harmonically spaced in frequency. This contrasts with the harmonic spacing of the resonances in a cylindrical plastic pipe, whose resonant frequencies fall in the ratio 1:3:5 etc. The second resonance of a didgeridoo (the note sounded by overblowing) is usually around an 11th higher than the fundamental frequency (a frequency ratio somewhat less than 3:1).

The vibration produced by the player's lips has harmonics, i.e., it has frequency components falling exactly in the ratio 1:2:3 etc. However, the non-harmonic spacing of the instrument's resonances means that the harmonics of the fundamental note are not systematically assisted by instrument resonances, as is usually the case for Western wind instruments (e.g., in a clarinet, the 1st 3rd and 5th harmonics of the reed are assisted by resonances of the bore, at least for notes in the low range).

Sufficiently strong resonances of the vocal tract can strongly influence the timbre of the instrument. At some frequencies, whose values depend on the position of the player's tongue, resonances of the vocal tract inhibit the oscillatory flow of air into the instrument. Bands of frequencies that are not thus inhibited produce formants in the output sound. These formants, and especially their variation during the inhalation and exhalation phases of circular breathing, give the instrument its readily recognizable sound.

Other variations in the didgeridoo's sound can be made by adding vocalizations to the drone. Most of the vocalizations are related to sounds emitted by Australian animals, such as the dingo or the kookaburra. To produce these sounds, the players simply have to use their vocal cords to produce the sounds of the animals whilst continuing to blow air through the instrument. The results range from very high-pitched sounds to much lower guttural vibrations. Adding vocalizations increases the complexity of the playing.

Cultural significance

Traditionally and originally, the didgeridoo was primarily played as an accompaniment to ceremonial dancing and singing, however, it was also common for didgeridoos to be played for solo or recreational purposes outside of ceremonial gatherings. For surviving Aboriginal groups of northern Australia, the didgeridoo is still an integral part of ceremonial life, as it accompanies singers and dancers in surviving cultural ceremonies. Today, the majority of didgeridoo playing is for recreational purposes in both Indigenous Australian communities and elsewhere around the world.

Pair sticks, sometimes called clapsticks or bilma, establish the beat for the songs during ceremonies. The rhythm of the didgeridoo and the beat of the clapsticks are precise, and these patterns have been handed down for many generations. Traditionally, only men play the didgeridoo and sing during ceremonial occasions, whilst both men and women may dance. Female didgeridoo players did exist, although their playing generally took place in an informal context and was not specifically encouraged. Linda Barwick, an ethnomusicologist, says that traditionally women have not played the didgeridoo in ceremony, but in informal situations there is no prohibition in the Dreaming Law.[10] On September 3, 2008, however, publisher Harper Collins issued a public apology for its book "The Daring Book for Girls", scheduled to be published in October, which openly encouraged girls to play the instrument.[11][12]

Didgeridoo in popular culture

The didgeridoo also became a role playing instrument in the experimental and avant-garde music scene. Industrial music bands like Test Department and Militia generated sounds from this instrument and used them in their industrial performances, linking ecology to industry, influenced by ethnic music and culture.

It has also been an instrument used for the fusion of tribal rhythms with a black metal sound, a music project called Naakhum that used the paganism of the Australian tribes and many others as an approach.

Souvenir didgeridoos

Perhaps the majority of didgeridoos manufactured today are purely for souvenir purposes. It is far more common to find didgeridoos made of non-native timbers, decorated incorrectly by non-indigenous artists displaying merely colourful designs or emulated dot patterns and no traditional dreamtime stories or generational designs. These souvenir didgeridoos also often vary widely in size and shape, many being thinner and straighter. As a result of the inadequate wood types, shapes and lengths, souvenir didgeridoos can rarely be used as musical instruments.

Decoration of souvenir didgeridoos is often seen by indigenous communities as offensive, inappropriate, inadequate, inaccurate and in many cases, misleading. The copying of traditional artwork is also used to sell these didgeridoos to unsuspecting tourists.

Health benefits

A 2005 study in the British Medical Journal found that learning and practicing the didgeridoo helped reduce snoring and sleep apnea by strengthening muscles in the upper airway, thus reducing their tendency to collapse during sleep.[13] This strengthening occurs after the player has mastered the circular breathing technique.

See also

- List of didgeridoo players

- Indigenous Australian music

- Native American flute

- Modern didgeridoo designs

Selected bibliography

- Ah Chee Ngala, P., Cowell C. (1996): How to Play the Didgeridoo - and history. ISBN 0646328409

- Chaloupka, G. (1993): Journey in Time. Reed, Sydney.

- Cope, Jonathan (2000): How to Play the Didgeridoo: a practical guide for everyone. ISBN 0-9539811-0-X.

- Jones, T. A. (1967): "The didjeridu. Some comparisons of its typology and musical functions with similar instruments throughout the world". Studies in Music 1, pp. 23–55.

- Kaye, Peter (1987): "How to Play the Didjeridu of the Australian Aboriginal - A Newcomer's Guide.

- Kennedy, K. (1933): "Instruments of music used by the Australian Aborigines". Mankind (August edition), pp. 147–157.

- Lindner, D. (ed) (2005): The Didgeridoo Phenomenon. From Ancient Times to the Modern Age. Traumzeit-Verlag, Germany.

- Moyle, A. M. (1981): "The Australian didjeridu: A late musical intrusion". in World Archaeology, 12(3), 321–31.

- Neuenfeldt, K. (ed) (1997): The didjeridu: From Arnhem Land to Internet. Sydney: J. Libbey/Perfect Beat Publications.

References

- ↑ Brass Instruments, BBC. [1]

- ↑ Kakadu National Park - Rock art styles

- ↑ George Chaloupka, Journey in Time, p. 189).

- ↑ http://www.flinders.edu.au/news/articles/?fj09v13s02

- ↑ The Didgeridoo and Aboriginal Culture Aboriginal Australia Art and Culture Centre of Alice Springs

- ↑ Taylor R., Cloake J, and Forner J. (2002) Harvesting rates of a Yolgnu harvester and comparison of selection of didjeridu by the Yolngu and Jawoyn, Harvesting of didjeridu by Aboriginal people and their participation in the industry in the Northern Territory (ed. R. Taylor) pp. 25–31. Report to AFFA Australia. Northern Territory Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Environment, Palmerston, NT.

- ↑ Wade-Matthews, M., Thompson, W., The Encyclopedia of Music, 2004, pp184-185. ISBN 0 760 76243 0

- ↑ Wade-Matthews,M., Illustrated Encyclopedia Musical Instruments, 2003, Lorenz Books, p95. ISBN 1 357 91086 42

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 A Baines, The Oxford Companion to Musical Instruments OUP 1992

- ↑ Women can play didgeridoo - taboo incites sales

- ↑ Didgeridoo book upsets Aborigines, BBC

- ↑ 'Daring Book for Girls' breaks didgeridoo taboo in Australia

- ↑ Puhan MA, Suarez A, Lo Cascio C et al. (2005). "Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: randomised controlled trial". BMJ 332 (7536): 266–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.38705.470590.55. PMID 16377643. PMC 1360393. http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/332/7536/266.

External links

- iDIDJ Australian Didgeridoo Cultural Hub

- Worldwide Didgeridoo Network - World's largest didgeridoo community with members from all over the world

- The Didjeridu W3 Server

- The physics of the didj

- Didgeridoo acoustics from the University of New South Wales

- Short and Simple Explanation of Circular Breathing Technique on the Didgeridoo

- Database of audio recordings of traditional Arnhem Land music, samples included, many with didgeridoo

- The Didjeridu: A Guide By Joe Cheal - General info on the didgeridoo, with citations and references

- BioloDidje Kezako | Breath | Technics | Making | Photos... (translations available)

- What's That Sound....The Didgeridoo

- Yidakiwuy Dhawu Miwatjngurunydja comprehensive site by traditional owners of the instrument

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||