Deuterostome

| Deuterostomes Fossil range: Late Ediacaran – Recent |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Sea cucumbers and other echinoderms are deuterostomes. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| (unranked): | Bilateria |

| Superphylum: | Deuterostomia Grobben, 1908 |

| Phyla | |

|

|

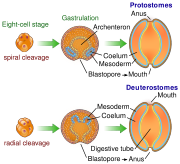

Deuterostomes (taxonomic term: Deuterostomia; from the Greek: "second mouth") are a superphylum of animals. They are a subtaxon of the Bilateria branch of the subregnum Eumetazoa, and are opposed to the protostomes. Deuterostomes are distinguished by their embryonic development; in deuterostomes, the first opening (the blastopore) becomes the anus, while in protostomes it becomes the mouth. Deuterostomes are also known as enterocoelomates because their coelom develops through enterocoely.

There are four extant phyla of deuterostomes:

- Phylum Chordata (vertebrates and their kin)

- Phylum Echinodermata (sea stars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, etc.)

- Phylum Hemichordata (acorn worms and possibly graptolites)

- Phylum Xenoturbellida (2 species of worm-like animals)

The phylum Chaetognatha (arrow worms) may also belong here. Extinct groups may include the phylum Vetulicolia. Echinodermata, Hemichordata and Xenoturbellida form the clade Ambulacraria.[1]

In both deuterostomes and protostomes, a zygote first develops into a hollow ball of cells, called a blastula. In deuterostomes, the early divisions occur parallel or perpendicular to the polar axis. This is called radial cleavage, and also occurs in certain protostomes, such as the lophophorates. Most deuterostomes display indeterminate cleavage, in which the developmental fate of the cells in the developing embryo are not determined by the identity of the parent cell. Thus if the first four cells are separated, each cell is capable of forming a complete small larva, and if a cell is removed from the blastula the other cells will compensate.

In deuterostomes the mesoderm forms as evaginations of the developed gut that pinch off, forming the coelom. This is called enterocoely.

Both the Hemichordata and Chordata have gill slits, and primitive fossil echinoderms also show signs of gill slits. A hollow nerve cord is found in all chordates, including tunicates (in the larval stage). Some hemichordates also have a tubular nerve cord. In the early embryonic stage it looks like the hollow nerve cord of chordates. Because of the degenerated nervous system of echinoderms, it is not possible to discern much about their ancestors in this matter, but based on different facts it is quite possible that all the present deuterostomes evolved from a common ancestor that had gill slits, a hollow nerve cord and a segmented body. It could have resembled the small group of Cambrian deuterostomes named Vetulicolia.

Contents |

Formation of mouth and anus

Deuterostome means "secondary mouth", and related to the fact that after the anus forms, a secondary opening forms in deuterostome embryos that goes on to be the mouth; the gut tunnels down from the mouth to anus to connect the two.

Origins

The majority of animals more complex than jellyfish and other Cnidarians are split into two groups, the protostomes and deuterostomes, and chordates are deuterostomes.[2] It seems very likely that 555 million years old Kimberella was a member of the protostomes.[3][4] If so, this means that the protostome and deuterostome lineages must have split some time before Kimberella appeared — at least 558 million years ago, and hence well before the start of the Cambrian 542 million years ago.[2] The Ediacaran fossil Ernietta, from about 549 to 543 million years ago, may represent a deuterostome animal.[5]

Fossils of one major deuterostome group, the echinoderms (whose modern members include sea stars, sea urchins and crinoids) are quite common from the start of the Cambrian, 542 million years ago.[6] The Mid Cambrian fossil Rhabdotubus johanssoni has been interpreted as a pterobranch hemichordate.[7] Opinions differ about whether the Chengjiang fauna fossil Yunnanozoon, from the earlier Cambrian, was a hemichordate or chordate.[8][9] Another Chenjiang fossil, Haikouella lanceolata, also from the Chengjiang fauna, is interpreted as a chordate and possibly a craniate, as it shows signs of a heart, arteries, gill filaments, a tail, a neural chord with a brain at the front end, and possibly eyes — although it also had short tentacles round its mouth.[9] Haikouichthys and Myllokunmingia, also from the Chenjiang fauna, are regarded as fish.[10][11] Pikaia, discovered much earlier but from the Mid Cambrian Burgess Shale, is also regarded as a primitive chordate.[12] On the other hand fossils of early chordates are very rare, since non-vertebrate chordates have no bones or teeth, and none have been reported for the rest of the Cambrian.

References

- ↑ S. J. Bourlat, T. Juliusdottir, C. J. Lowe, R. Freeman, J. Aronowicz, M. Kirschner, E. S. Lander, M. Thorndyke, H. Nakano, A. B. Kohn, A. Heyland, L. L. Moroz, R. R. Copley, M. J. Telford (2006). "Deuterostome phylogeny reveals monophyletic chordates and the new phylum Xenoturbellida". Nature 444: 85–88.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Erwin, Douglas H.; Eric H. Davidson (1 July 2002). "The last common bilaterian ancestor". Development 129 (13): 3021–3032. PMID 12070079. http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/129/13/3021.

- ↑ New data on Kimberella, the Vendian mollusc-like organism (White sea region, Russia): palaeoecological and evolutionary implications (2007), "Fedonkin, M.A.; Simonetta, A; Ivantsov, A.Y.", in Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Komarower, Patricia, The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota, Special publications, 286, London: Geological Society, pp. 157–179, doi:10.1144/SP286.12, ISBN 9781862392335, OCLC 191881597 156823511 191881597

- ↑ Butterfield, N.J. (2006). "Hooking some stem-group "worms": fossil lophotrochozoans in the Burgess Shale". Bioessays 28 (12): 1161–6. doi:10.1002/bies.20507. PMID 17120226.

- ↑ Dzik , J. (June 1999). "Organic membranous skeleton of the Precambrian metazoans from Namibia". Geology 27 (6): 519–522. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0519:OMSOTP>2.3.CO;2. http://geology.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/27/6/519. Retrieved 2008-09-22. Ernietta is from the Kuibis formation, approximate date given by Waggoner, B. (2003). "The Ediacaran Biotas in Space and Time". Integrative and Comparative Biology 43 (1): 104–113. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.104. http://icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/43/1/104. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ↑ Bengtson, S. (2004). Early skeletal fossils. In Lipps, J.H., and Waggoner, B.M.. "Neoproterozoic–Cambrian Biological Revolutions" (PDF). Palentological Society Papers 10: 67–78. http://www.cosmonova.org/download/18.4e32c81078a8d9249800021554/Bengtson2004ESF.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ Bengtson, S., and Urbanek, A. (October 2007). "Rhabdotubus, a Middle Cambrian rhabdopleurid hemichordate". Lethaia 19 (4): 293–308. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1986.tb00743.x. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/120025616/abstract. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Shu, D., Zhang, X. and Chen, L. (April 1996). "Reinterpretation of Yunnanozoon as the earliest known hemichordate". Nature 380: 428–430. doi:10.1038/380428a0. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v380/n6573/abs/380428a0.html. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Chen, J-Y., Hang, D-Y., and Li, C.W. (December 1999). "An early Cambrian craniate-like chordate". Nature 402: 518–522. doi:10.1038/990080. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v402/n6761/abs/402518a0.html. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Shu, D-G., Conway Morris, S., and Han, J., et al. (January 2003). "Head and backbone of the Early Cambrian vertebrate Haikouichthys". Nature 421: 526–529. doi:10.1038/nature01264. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v421/n6922/abs/nature01264.html. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ↑ Shu, D-G., Conway Morris, S., and Zhang, X-L. (November 1999). "Lower Cambrian vertebrates from south China" (PDF). Nature 402: 42. doi:10.1038/46965. http://www.bios.niu.edu/davis/bios458/Shu1.pdf. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Shu, D-G., Conway Morris, S., and Zhang, X-L. (November 1996). "A Pikaia-like chordate from the Lower Cambrian of China". Nature 384: 157–158. doi:10.1038/384157a0. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v384/n6605/abs/384157a0.html. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

External links

- UCMP-Deuterostomes

- Deciphering deuterostome phylogeny: molecular, morphological and palaeontological perspectives

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||