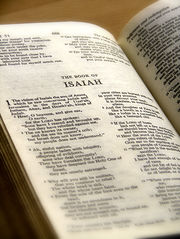

Book of Isaiah

The Book of Isaiah (Hebrew: ספר ישעיה) is a book of the Bible traditionally attributed to the Prophet Isaiah, who lived in the second half of the 8th century BC.[1] In the first 39 chapters, Isaiah prophesies doom for a sinful Judah and for all the nations of the world that oppose God. The last 27 chapters prophesy the restoration of the nation of Israel. This section includes the Songs of the Suffering Servant, four separate passages that Christians believe prefigure the coming of Jesus Christ, and which are traditionally thought by Jews to refer to the nation of Israel. This second of the book's two major sections also includes prophecies of a new creation in God's glorious future kingdom.[2]

There is considerable debate about the dating of the text; one widely accepted critical hypothesis suggests that much if not most of the text was not written in the 8th century BC.[3] Tradition ascribes the Book of Isaiah to a single author, Isaiah himself. Modern scholarship suggests the text has two or three authors. This later author or authors, and their work or works, are known as Deutero- or Second Isaiah and Trito- or Third Isaiah respectively.[2][4]

Contents |

Content

|

Part of a series

of articles on the |

|---|

| Tanakh (Books common to all Christian and Judaic canons) |

| Genesis · Exodus · Leviticus · Numbers · Deuteronomy · Joshua · Judges · Ruth · 1–2 Samuel · 1–2 Kings · 1–2 Chronicles · Ezra (Esdras) · Nehemiah · Esther · Job · Psalms · Proverbs · Ecclesiastes · Song of Songs · Isaiah · Jeremiah · Lamentations · Ezekiel · Daniel · Minor prophets |

| Deuterocanon |

| Tobit · Judith · 1 Maccabees · 2 Maccabees · Wisdom (of Solomon) · Sirach · Baruch · Letter of Jeremiah · Additions to Daniel · Additions to Esther |

| Greek and Slavonic Orthodox canon |

| 1 Esdras · 3 Maccabees · Prayer of Manasseh · Psalm 151 |

| Georgian Orthodox canon |

| 4 Maccabees · 2 Esdras |

| Ethiopian Orthodox "narrow" canon |

| Apocalypse of Ezra · Jubilees · Enoch · 1–3 Meqabyan · 4 Baruch |

| Syriac Peshitta |

| Psalms 152–155 · 2 Baruch · Letter of Baruch |

|

|

The 66 chapters of Isaiah consist primarily of prophecies of Babylon, Assyria, Philistia, Moab, Syria, Israel (the northern kingdom), Ethiopia, Egypt, Arabia, and Phoenicia. The prophesies concerning them can be summarized as saying that God is the God of the whole earth, and that nations which think of themselves as secure in their own power might well be conquered by other nations, at God's command.

The first 39 chapters are thought to be authored by Isaiah, with the remaining chapters added later by one or more scribes working in Isaiah's tradition. See the discussion in the Authorship section below.

Isaiah 1-39

Chapters 1-5 and 28-29 prophesy judgment against Judah itself. Judah thinks itself safe because of its covenant relationship with God. However, God tells Judah (through Isaiah) that the covenant cannot protect them when they have broken it by idolatry, the worship of other gods, and by acts of injustice and cruelty, which oppose God's law.

Some exceptions to this overall foretelling of doom do occur, throughout the early chapters of the book. Chapter 6 describes Isaiah's call to be a prophet of God. Chapters 35-39 provide historical material about King Hezekiah and his triumph of faith in God.

Chapters 24-34, while too complex to characterize easily, are primarily concerned with prophecies of a "Messiah", a person anointed or given power by God, and of the Messiah's kingdom, where justice and righteousness will reign. This section is seen by Jews as describing an actual king, a descendant of their great king, David, who will make Judah a great kingdom and Jerusalem a truly holy city. It is traditionally seen by Christians as describing Jesus. A number of modern scholars believe that it describes, in somewhat idealized terms, King Hezekiah, who was a descendant of David, and who tried to make Jerusalem into a holy city. Muslims have claimed that verse 29:12 describes the prophet Muhammad: "And the book will be delivered to him that is not learned, saying Read this, I pray thee: and he saith, I am not learned", as Muhammad is believed to have been illiterate and the very first words revealed to him by God were "read" or "recite" and he answered "I can not read".

Isaiah 40-66

The prophecy continues with what some have called “The Book of Comfort” which begins in chapter 40 and completes the writing. In the first eight chapters of this book of comfort, Isaiah prophesies the deliverance of the Jews from the hands of the Babylonians and restoration of Israel as a unified nation in the land promised to them by God. Isaiah reaffirms that the Jews are indeed the chosen people of God in chapter 44 and that Yahweh is the only God for the Jews (and the only God of the universe) as he will show his power over the mighty rulers of Babylon in due time in chapter 46. In chapter 45:1, the Persian ruler Cyrus is named as the person of power who will overthrow the Babylonians and allow the return of Israel to their original land.

The remaining chapters of the book contain prophecies of the future glory of Zion. A "suffering servant" is referred to (esp. ch. 53). Rabbinic Judaism understands this as a metaphor for Israel; Christians see it as referring to the Messiah.[5] Although there is still the mention of judgment of false worshippers and idolaters (65 & 66), the book ends with a message of hope of a righteous ruler who extends salvation to his righteous subjects living in the Lord’s kingdom on earth.

Supporters of two authors division use the term Deutero-Isaiah in reference to chapters 40-66, but to the supporters of three divisions in authorship this term usually refers to chapters 40-55 only.

A popular and well known extract from 40:6 is the quote "All flesh is grass".

Historical background

Isaiah is traditionally believed to have lived in the late eighth century BC. He was part of the upper class but urged care of the downtrodden. At the end, he was loyal to King Hezekiah, but disagreed with the King's attempts to forge alliances with Egypt and Babylon in response to the Assyrian threat.

Isaiah prophesied during the reigns of four kings: Uzziah (also known as Azariah), Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah. According to tradition, he was martyred during the reign of Manasseh, who came to the throne in 687 BC, by being cut in two by a wooden saw. That he is described as having ready access to the kings would suggest an aristocratic origin.

This was the time of the divided kingdom, with Israel in the north and Judah in the south. There was prosperity for both the kingdoms during Isaiah’s youth with little foreign interference. Jeroboam II ruled in the north and Uzziah in the south. The small kingdoms of Palestine, as well as Syria, were under the influence of Egypt. However, in 745 BC, Tiglath-pileser III came to the throne of Assyria. He was interested in Assyrian expansionism, especially to the west; and 2 Kings 15:17-22 mentions that King Menahem of Israel paid tribute to him ("King Pul").

Syro-Ephraimite War

Because of the threat from Tiglath-pileser III, Syria (or "Aram") and Israel (led now by Pekah) tried to force Judah to ally with them around 734 BC. Ahaz was on the throne of Judah then. He was advised by Isaiah to trust in the Lord, but, instead, he called to Assyria for help. Pekah of Israel and Rezin of Syria attacked Judah and inflicted damage on it before Assyria came to its aid, but there would be more serious religious consequences of Ahaz’s refusal to accept the Lord’s guidance through Isaiah.

Fall of Syria and Samaria

With Israel under King Pekah no longer loyal, Tiglath-pileser attacked in 733 BC. He took much of the land of Israel (2 Kings 15:29-30) leaving only the city of Samaria and its surroundings independent.[6] Judah, however, was not involved.

Damascus, capital of Syria, was taken by the Assyrians in 732. Tiglath–pileser died in 727 BC, raising false hopes for the Palestinian countries. Ahaz died a year later. Isaiah warned Philistia and the other countries not to revolt against Assyria. Hoshea, then king of Samaria, withheld tribute to Assyria. Consequently, Shalmaneser V, the new king of Assyria, laid siege to Samaria for 3 years, and his successor, Sargon II, took the city and deported 27,000 Israelites to northern parts of the Assyrian empire. This marked the end of the Northern Kingdom of Israel forever, as its population was taken into exile and dispersed amongst Assyrian provinces. It is as a result of this exile that reference is made to Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

There was peace in the area for 10 years, but then, Sargon returned in 711 BC to crush a coalition of Egypt and the Philistines. Judah had stayed out of this conflict, Hezekiah wisely listening to Isaiah’s advice.

Babylon

Merodach-Baladan took power in Babylon in 721 BC. Sargon took Babylon without a fight in 711 BC, but after Sargon’s death, Merodach-Baladan rebelled against Sargon's successor Sennacherib. Babylon was defeated this time but would revive in another century to defeat Assyria, subjugate the Jews and destroy Jerusalem.

Hezekiah and Sennacherib

Sennacherib came to the throne of Assyria in 705 BC. He had trouble immediately – with Ethiopian monarchs in Egypt (reference to Ethiopia here refers to present day north Sudan) and with the Babylonian leader, Merodach-Baladan. Despite Isaiah’s warnings, Hezekiah became involved as well. The Assyrians invaded the area, taking 46 towns before putting Jerusalem under siege. Isaiah persuaded Hezekiah to trust in the Lord and Jerusalem was spared.

Themes

Isaiah is concerned with the connection between worship and ethical behavior. One of his major themes is Yahweh's refusal to accept the ritual worship of those who are treating others with cruelty and injustice.

Isaiah speaks also of idolatry, which was common at the time. The Canaanite worship, which involved fertility rites, including sexual practices forbidden by Jewish law, had become popular among the Jewish people. Isaiah picks up on a theme used by other prophets and tells Judah that the nation of Israel is like a wife who is committing adultery, having run away from her true husband, YHWH.

An important theme is that YHWH is the God of the whole earth. Many gods of the time were believed to be local gods or national gods who could participate in warfare and be defeated by each other. The concern of these gods was the protection of their own particular nations.

No one can defeat YHWH; if YHWH's people suffer defeat in battle, it is only because he permits it to happen. Furthermore, Yahweh is concerned with more than the Jewish people. He has called Judah and Israel his covenant people for the specific purpose of teaching the world about him.

A unifying theme found throughout the Book of Isaiah is the use of the expression of "the Holy One of Israel". Some Christians interpret this as a title for Christ. It is found 12 times in chapters 1-39 and 14 times in chapters 40-66. This expression appears only 6 times within the Old Testament outside the book of Isaiah[7].

A final thematic goal that Isaiah constantly leans toward throughout the writing is the establishment of Yahweh's kingdom on earth, with rulers and subjects who strive to live by his will.

Authorship

One of the most critically debated issues in Isaiah is the proposition that it may have been the work of more than a single author. Different proposals suggest that there have been two or three main authors, while alternative views suggest an additional number of minor authors or editors.[8]

It is a matter of common agreement among scholars[9] that a division occurs at the end of chapter 39 and that subsequent portions were written by one or more additional authors. The typical objections to single authorship of the book of Isaiah are as follows:

- Anachronisms → Passages of Isaiah 40-66 contain some events and details that did not occur in Isaiah's own lifetime, such as the rise of Babylon as the world power, the destruction of Jerusalem, and the rise of Cyrus the Great and his overthrow of the Babylonian Empire. This is generally explained by either considering Isaiah to have been given such information by divine means, or by considering the later sections of the book to be, not written by Isaiah, but written by those who lived later than Isaiah himself. The mainstream scholarly understanding reflects the latter interpretation. Yet O. T. Allis argues that this comes from a denial that there can in fact be such as thing as distinct prophetic foresight of the distant future.[10] Allis goes on to argue that the Cyrus prophecy is indeed distant future, based on the numerico-climactic structure of Isaiah 44:24-28.[11] Yet the mention of Cyrus by name (chs. 44:28; 45:1) is regarded by scholars as compelling evidence that these chapters were written during the time of Cyrus, that is, in the second half of the 6th century B. C. According to scholar R. N. Whybray, the author of Deutero-Isaiah (chapters 40-55) was mistaken for he thought that Cyrus would destroy Babylon but he did not. Cyrus made it more splendid than ever. But he did allow the Jewish exiles to return home, though not in the triumphant manner which Deutero-Isaiah expected.[12]

- Anonymity → That is to say that Isaiah’s name is suddenly not used from chapter 40-66.

- Style → There is a sudden change in the book after chapter 40 in the style and in the theology presented.[8] Numerous words and phrases found in one section are not found in the other.[13]

- Historical Situation → The first portion of the book of Isaiah speaks of an impending judgment which will befall the wicked Israelites whereas the later portion of the book discusses God's mercy and restoration as though the exile were already a present reality. Isaiah 40-66 presupposes the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Babylonians in 587 BCE as an accomplished fact(44:26,28, 49:19, 51:17-20, 52:9, 60:10, 63:18, 64:10-11), yet this catastrophe is merely anticipated in chapters 1-39. Further, the fall of Babylon in 539 BCE is seen in the immediate future in chapters 40-55 and in the past in 56-66, yet Babylon was not even a threat much less an enemy to Judah in the 8th century BCE.[13]

Through chapter 39 most of the material is Isaiah's and is an accurate account of the situation in eighth-century Judah, even if chapters 13-14, 24-27, and 34-35 could be the work of his disciples and near contemporaries.[14]

Supporters of the three authors proposal see a further division at the end of chapter 55, and propose to divide the Book of Isaiah as follows:[15]

- Chapters 1 to 39 (First Isaiah, Proto-Isaiah or Original Isaiah): preached between 740 and 687 BC. Isaiah is here a city person who insisted upon faith and was fearless in opposing leaders.[14]

- Chapters 40 to 55 (Second Isaiah or Deutero-Isaiah): probably written by an anonymous poet near the end of the Babylonian captivity.[15]:418 Isaiah is here a master of sound and music with sweeping visions of mountains collapsing and valleys lifted up.[14]

- Chapters 56 to 66 (Third Isaiah or Trito-Isaiah): written by anonymous disciples committed to continuing Isaiah's work in the years immediately after the return from Babylon.[15]:444 Isaiah is dreamed of new heavens and new earth.[14]

Scholars who disagree with the three author hypothesis suggest that the last ten chapters of the Book of Isaiah were written by Deutero-Isaiah at a later date.[16]

It has been suggested that the authorship of Isaiah took place over the span of as much as four centuries.[17]

Traditional View

Jews and Christians have understood the book to have one author, Isaiah himself. The Talmud (Bava Basra 15a) says that the book of Isaiah was written by King Hezekiah and his assistants, of whom Chaim Dov Rabinowitz (1909–2001) says, in the introduction to his Daat Soferim Isaiah, may have lived long after Isaiah. Rabbi Joseph H. Hertz (1872–1946) wrote that the question of the book's authorship doesn't affect Jewish understanding of the book.[18]

For Christians, this belief is reinforced by the New Testament, which quotes passages from Isaiah 40-66, together with a specific identification of Isaiah as their author, no fewer than seven times (Matt. 3:3, 8:17, 12:18; John 1:23, 12:38-40; Rom. 10:16, 11:26). Specifically, John 12:38-40 quotes from Isaiah 53 and Isaiah 6 and ascribes each quotation to Isaiah. The ancient Jewish historian Josephus also attributes both sections of the book of Isaiah to a single author.

Among the Christian churches, the Eastern Orthodox churches and the Oriental Orthodox churches maintain a strong historical position that the book was written by Isaiah himself following the teachings of Saint Cyril of Alexandria and others. Sirach 48:22-28, of the Orthodox and Catholic Deuterocanon, implies that Isaiah prophesied the prophecy of Isaiah 44.

Servant Songs

Songs of the Suffering Servant (also called the Servant songs or Servant poems) were first identified by Bernhard Duhm in his 1892 commentary on Isaiah. The songs are four poems taken from the Book of Isaiah written about a certain "servant of YHWH." God calls the servant to lead the nations, but the servant is horribly abused. The servant sacrifices himself, accepting the punishment due others. In the end, he is rewarded. The traditional Jewish interpretation is that the Servant is a metaphor for the Jewish people,[19] an opinion shared by many contemporary scholars.[5] According to Duhm, the servant was some otherwise unknown individual, and the songs' author was a disciple. Various interpretations have followed: Zerubbabel, Jehoiachin, Moses, Cyrus the Great. Duhm proposed in his commentary that the songs were added by a poet with leprosy. Sigmund Mowinckel suggested that the songs referred to Isaiah himself but later abandoned that interpretation. Christians traditionally see the suffering servant as Jesus Christ.[5]

Some scholars (such as Barry Webb[20]) regard Isaiah 61:1-3 as a fifth servant song, although the word "servant" is not mentioned in the passage.

The first song

The first poem has God speaking of His selection of the Servant who will bring justice to earth. Here the Servant is described as God's agent of justice, a king* that brings justice in both royal and prophetic roles, yet justice is established neither by proclamation nor by force. He does not ecstatically announce salvation in the marketplace as prophets were bound to do but instead moves quietly and confidently to establish right religion. Isaiah 42:1-9

- There is no reference to a king in this passage. The final verse uses the phrase 'a light to the nations'. This is traditionally used to refer to the Nation Israel.

The second song

The second poem, written from the Servant's point of view, is an account of his pre-natal calling by God to lead both Israel and the nations. The Servant is now portrayed as the prophet of the Lord equipped and called to restore the nation to God. Yet, anticipating the fourth song, he is without success. Taken with the picture of the Servant in the first song, his success will come not by political or military action, but by becoming a light to the Gentiles. Ultimately his victory is in God's hands. Isaiah 49:1-13.

The third song

The third poem has a darker yet more confident tone than the others. Although the song gives a first-person description of how the Servant was beaten and abused, here the Servant is described both as teacher and learner who follows the path God places him on without pulling back. Echoing the first song's "a bruised reed he will not break," he sustains the weary with a word. His vindication is left in God's hands. Isaiah 50:4-9

The fourth song

The last, longest, and most famous Servant poem, is a speech by Yahweh announcing the destiny of the Servant. Isaiah 53 declares that the Servant intercedes for others, taking the punishments and afflictions of others. In the end, he is rewarded with an exalted position. Much of song makes reference to an unknown group*. See the many references to "we" and "our" in the song Isaiah 53:1-11 Early on the evaluation of the Servant by the "we" is negative: "we" esteemed him not, many were appalled by him, nothing in him was attractive to "us". But at the Servant's death the attitude of the "we" changes after verse 4 where the servant bears "our" iniquities, "our" sickness, by the servant's wounds "we" are healed. Posthumously, then, the Servant is vindicated by God. Because of its references to the vicarious sufferings of the servant, many Christians believe this song to be among the Messianic prophecies of Jesus. Isaiah 52:13-53:12 In Judaism these verses are taken to represent Israel, its sufferings and its redemption by Yahweh.

New Testament Allusions and Quotations

In the Gospels: The first song is directly quoted in the Gospel of Matthew 12:18-21. The fourth song's "He was numbered with the transgressors" Isaiah 53:12 is directly quoted in Luke 22:37. The fourth song's "Surely he bore our sicknesses" 53:4 is quoted in Matthew 8:17. "Ransom for many" in Matthew 20:28, Mark 10:45 and 14:24 is alluded to in Isaiah 53:10-11. "Suffer many things" in Mark 9:12 may refer to Isaiah 53:3. "Divide the spoil with the strong" Isaiah 53:12 may be referenced in Luke 11:22

In Acts and the Epistles: "Make many righteous" in Isaiah 53:11 is referred to in Romans 5:15-18 and in Acts 13:39. Paul reflects the fourth song in the following: "He was delivered up for our trespasses" Romans 4:25 "Many will be made righteous" Romans 5:19 "in the likeness of sinful flesh, condemned sin in the flesh" Romans 8.3 "Christ dies for our sins, in accordance with the scriptures" 1 Corinthians 15:3 The Kenosis passage portrays Christ as "taking the form of a servant" Philippians 2:6-11 1 Peter contains a number of allusions to the fourth song in chapter 2: "Christ also suffered for you"; "He committed no sin, neither was deceit found in his mouth"; "When he was reviled, he did not revile in return; when he suffered, he did not threaten"; "He himself bore our sins in his body"; "By his wounds you have been healed"; "straying like sheep" 1 Peter 2.21-25

Jewish scholars contend that New Testament accounts of Jesus included details invented to show that Jesus had fulfilled prophecy. They argue the authors of the New Testament delved into the Hebrew scripture and found passages which they reinterpreted to be about Jesus.[21] For instance Isaiah 7:14 is cited in Matthew 1:23 as evidence that the virgin birth of Jesus is foretold by the prophet Isaiah. However, Isaiah's original Hebrew, reads (transliterated): Hinneh ha-almah harah ve-yeldeth ben ve-karath shem-o immanuel. The word almah is part of the Hebrew phrase ha-almah hara, meaning "the almah is pregnant." Since the present tense is used, it is argued that the young woman was already pregnant and hence not a virgin. As such, the verse cannot be cited as a prediction of the future.[22] Jews understand that God indicated he was sending a "sign" in the days of Ahaz (who lived many centuries before Jesus). The Jewish tradition has accordingly never considered Isaiah 7:14 as a messianic prophecy. Jewish scholars argue that this is a Christian misinterpretation. [23]

Isaiah scroll

The 2,100-year old Isaiah Scroll is the only complete scroll in the cache of 220 biblical scrolls discovered in a cave in Qumran on the northwestern coast of the Dead Sea. Adolfo Roitman, curator of the Shrine of the Book where the Dead Sea scrolls are kept, says that Isaiah was the most popular prophet of the Second Temple period: 21 copies of the scroll were found in Qumran.[1]

References

| First Prophets |

|---|

| 1. Joshua |

| 2. Judges |

| 3. Samuel |

| 4. Kings |

| Later Prophets |

| 5. Isaiah |

| 6. Jeremiah |

| 7. Ezekiel |

| 8. 12 minor prophets |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/982919.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- ↑ Williamson, Hugh Godfrey Maturin The Book Called Isaiah, Oxford University Press 1994 ISBN 978-0-19-826360-9 p.1 [1]

- ↑ Kugel, pp. 558-562

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Servant Songs." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ Herrmann, Seigfried: A History of Israel in Old Testament Times

- ↑ "Introduction to the book of Isaiah". Zondervan. http://www.ibsstl.org/niv/studybible/isaiah.php. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1982). The international standard Bible encyclopedia. pp. 895–895. ISBN 9780802837820.

- ↑ Creelman, Harlan (1917). An Introduction to the Old Testament. The Macmillan company. pp. 172.

- ↑ O. T. Allis, The Unity of Isaiah: A Study in Prophecy (Nutley, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1977), p. 3.

- ↑ Allis, Unity of Isaiah, p. 79.

- ↑ Second Isaiah, R. N. Whybray

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mercer dictionary of the Bible

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 "Introduction to the Book of Isaiah". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. http://www.nccbuscc.org/nab/bible/isaiah/intro.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Boadt, Lawrence (1984). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction. ISBN 9780809126316.

- ↑ Kugel, p. 561

- ↑ John T. Willis, "Isaiah" section in The Transforming Word: One-Volume Commentary on the Bible, ed. Mark W. Hamilton et al. (Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian University Press, 2009): pp. 533-576 (quotation appears on p. 533), ISBN 978-0-89112-521-1. As indication of the fractious character of analysis of Isaiah authorship, no sooner was the print dry on Willis' statement before he was alleged to have "infidelic bias" (Wayne Jackson, "The ACU Commentary and the Unity of the Book of Isaiah" in Christian Courier, 2009 February 24 accessed 2009 August 29) by Christian Courier editor Wayne Jackson, fellow member with Willis in the Churches of Christ. In a commentary weighing almost 7 lb, extending to viii + 1127 pages, and containing numerous examples of analytical discussion influenced by contemporary scholarship (see Amazon.com site on Transforming Word), Willis' comment on the authorship of the book of Isaiah is the one point which Jackson chose to assay, even summoning to defense of the one-author position Gleason Archer and other fundamentalist commentators not necessarily compatible with either Willis or Jackson on other topics.

- ↑ "This question can be considered dispassionately. It touches no dogma, or any religious principle in Judaism; and, moreover, does not materially affect the understanding of the prophecies, or of the human conditions of the Jewish people that they have in view." -Rabbi Joseph H. Hertz

- ↑ Jews for Judaism, "Jews for Judaism FAQ," Accessed 2006-09-13. See also Ramban in his disputation.

- ↑ Barry G. Webb, The Message of Zechariah: Your Kingdom Come, Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2004, series "The Bible Speaks Today", page 42.

- ↑ A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Bruce Metzger

- ↑ The Second Jewish Book Of Why by Alfred Kolatch 1985

- ↑ Was She, or Was She not "A Virgin"?, Messiah Truth

- Childs, Brevard S. (2000-11). Isaiah (1st ed ed.). Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 555. ISBN 0664221432.

- Kugel, James L. (2008). How To Read the Bible. New York, NY: Free Press. pp. 538–568. ISBN 978-0-7432-3587-7.

External links

- Book of Isaiah (Hebrew) side-by-side with English)

- Book of Isaiah (English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org)

- Bible Gateway 35 languages/50 versions at GospelCom.net

- Unbound Bible 100+ languages/versions at Biola University

- Introduction to the book of Isaiah from the NIV Study Bible

- The ACU Commentary and the Unity of the Book of Isaiah

| Preceded by Kings in the Tanakh Song of Songs in the Protestant OT Sirach in the R. Catholic & Eastern OT |

Books of the Bible | Succeeded by Jeremiah |