Pethidine

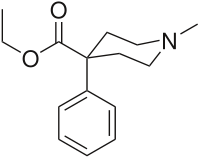

Pethidine (INN) or meperidine (USAN) (commonly referred to as Demerol but also referred to as: isonipecaine; lidol; pethanol; piridosal; Algil; Alodan; Centralgin; Dispadol; Dolantin; Mialgin (in Romania); Petidin Dolargan (in Poland);[1] Dolestine; Dolosal; Dolsin; Mefedina) is a fast-acting opioid analgesic drug. In the United States and Canada, it is more commonly known as meperidine or by its brand name Demerol.[2]

Pethidine was the first synthetic opioid synthesized in 1932 as a potential anti-spasmodic agent by the chemist Otto Eislib. Its analgesic properties were first recognized by Otto Schaumann working for IG Farben, Germany.[3]

Pethidine is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe pain, and is delivered as its hydrochloride salt in tablets, as a syrup, or by intramuscular or intravenous injection. For much of the 20th century, pethidine was the opioid of choice for many physicians; in 1983 60% of doctors prescribed it for acute pain and 22% for chronic severe pain.[4]

Compared to morphine, pethidine was supposed to be safer and carry less risk of addiction, and to be superior in treating the pain associated with biliary spasm or renal colic due to its putative antispasmodic effects. In fact, pethidine is no more effective than morphine at treating biliary or renal pain, and its low potency, short duration of action, and unique toxicity (i.e., seizures, delirium, other neuropsychological effects) relative to other available opioid analgesics have seen it fall out of favor in recent years for all but a very few, very specific indications.[5] Several countries, including Australia, have put strict limits on its use.[6] Nevertheless, some physicians continue to use it as a first line strong opioid.

Pharmacodynamics/mechanism of action

Pethidine's efficacy as an analgesic was discovered almost accidentally; it was synthesized in 1939 at an IG Farben laboratory as an antimuscarinic agent.[7] Pethidine also has structural similarities to atropine and other tropane alkaloids and may have some of their effects and side effects.[1] Pethidine exerts its analgesic effects by the same mechanism as morphine, by acting as an agonist at the μ-opioid receptor. In addition to its strong opioidergic and anticholinergic effects, it has local anesthetic activity related to its interactions with sodium ion channels.

Pethidine's apparent in vitro efficacy as an "antispasmodic" is due to its local anesthetic effects. It does not, contrary to popular belief, have antispasmodic effects in vivo.[8] Pethidine also has stimulant effects mediated by its inhibition of the dopamine transporter (DAT) and norepinephrine transporter (NAT). Because of its DAT inhibitory action, pethidine will substitute for cocaine in animals trained to discriminate cocaine from saline.[9]

Several analogues of pethidine have been synthesized that are potent inhibitors of the reuptake of the monoamine neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine via DAT and NAT.[10][11] It has also been associated with cases of serotonin syndrome, suggesting some interaction with serotonergic neurons, but the relationship has not been definitively demonstrated.[6][7][9][11] It is more lipid-soluble than morphine, resulting in a faster onset of action. Its duration of clinical effect is 120–150 minutes although it is typically administered in 4-6 hour intervals. Pethidine has been shown to be less effective than morphine, diamorphine or hydromorphone at easing severe pain, or pain associated with movement or coughing.[7][9][11]

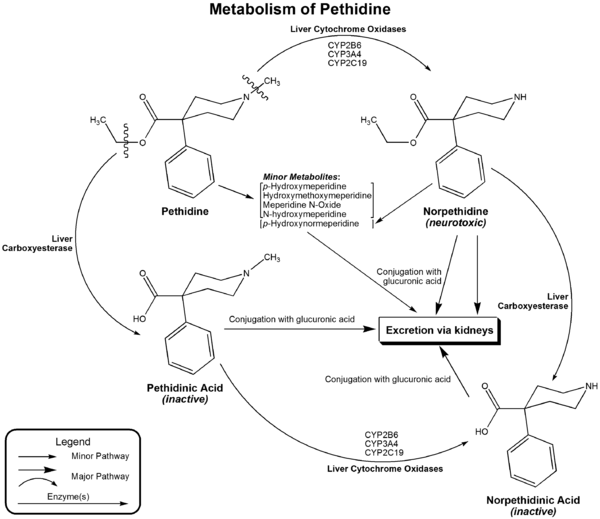

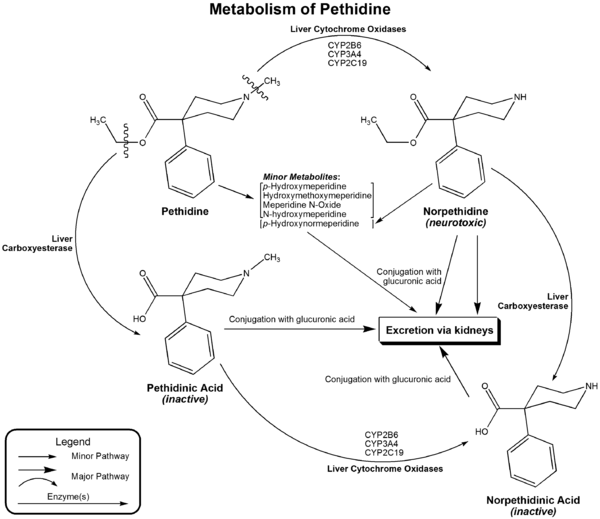

Like other opioid drugs, pethidine has the potential to cause physical dependence or addiction. Pethidine may be more likely to be abused than other prescription opioids, perhaps because of its rapid onset of action.[12] When compared with oxycodone, hydromorphone, and placebo, pethidine was consistently associated with more euphoria, difficulty concentrating, confusion, and impaired psychomotor and cognitive performance when administered to healthy volunteers.[13] The especially severe side effects unique to pethidine among opioids — serotonin syndrome, seizures, delirium, dysphoria, tremor — are primarily or entirely due to the action of its metabolite, norpethidine.[7][14]); accumulating with regular administration, or in renal failure. Norpethidine is toxic and has convulsant and hallucinogenic effects. The toxic effects mediated by the metabolites cannot be countered with opioid receptor antagonists such as naloxone or naltrexone and are probably primarily due to norpethidine's anticholinergic activity probably due to its structural similarity to atropine though its pharmacology has not been thoroughly explored. The neurotoxicity of pethidine's metabolites is a unique feature of pethidine compared to other opioids. Pethidine's metabolites are further conjugated with glucuronic acid and excreted into the urine.

Interactions

Pethidine has serious interactions that can be dangerous with MAOIs (e.g., furazolidone, isocarboxazid, moclobemide, phenelzine, procarbazine, selegiline, tranylcypromine). Such patients may suffer agitation, delirium, headache, convulsions, and/or hyperthermia. Fatal interactions have been reported including the death of Libby Zion.[15] It is thought to be caused by an increase in cerebral serotonin concentrations. It is possible that pethidine can also interact with a number of other medications, including muscle relaxants, some antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and alcohol.

Pethidine is also relatively contraindicated for use when a patient is suffering from liver, or kidney disease, has a history of seizures or epilepsy, has an enlarged prostate or urinary retention problems, or suffers from hypothyroidism, asthma, or Addison's disease.

Adverse effects

The adverse effects of pethidine administration are primarily those of the opioids as a class: nausea, vomiting, sedation, dizziness, diaphoresis, miosis, urinary retention and constipation. Overdosage can cause muscle flaccidity, respiratory depression, obtundedness, cold and clammy skin, hypotension and coma. A narcotic antagonist such as naloxone is indicated to reverse respiratory depression. Serotonin syndrome has occurred in patients receiving concurrent antidepressant therapy with selective serotonon reuptake inhibitors or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Convulsive seizures sometimes observed in patients receiving parenteral pethidine on a chronic basis have been attributed to accumumulation in plasma of the metabolite norpethidine (normeperidine). Fatalities have occurred following either oral or intravenous pethidine overdosage.[16] [17]

Hazardous use, harmful use, dependence, and diversion

Trends

In data from the U.S. Drug Abuse Warning Network, mentions of hazardous or harmful use of pethidine declined between 1997 and 2002, in contrast to increases for fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, and oxycodone.[18] The number of dosage units of pethidine that were reported lost or stolen in the U.S. increased 16.2% between 2000 and 2003, from 32,447 to 37,687.[19]

Notes

This article uses the terms "hazardous use", "harmful use", and "dependence" in accordance with

Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms published by the

World Health Organization (WHO) in 1994.

[20] In WHO usage, the first two terms replace the term "abuse" and the third term replaces the term "addiction".

[20]References

- ↑ "Lekopedia - Dolargan". jestemchory.pl. http://www.jestemchory.pl/lek.via?id=99824&str=19&l=d&r=h&VSID=4c69dc1b3a23b828e497dea2157f0263. Retrieved 2006-08-01.

- ↑ Demerol RxList. Retrieved 19 Jun. 2006.

- ↑ Michaelis, Martin; Schölkens, Bernward; Rudolphi, Karl (april 2007). "An anthology from Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (Springer Berlin) 375 (2): 81–84. doi:10.1007/s00210-007-0136-z. ISSN:0364-5134.

- ↑ Kaiko, Robert F.; Kathleen M. Foley, Patricia Y. Grabinski, George Heidrich, Ada G. Rogers, Charles E. Inturrisi, Marcus M. Reidenberg (February 1983). "Central Nervous System Excitatory Effects of Meperidine in Cancer Patients". Annals of Neurology (Wiley Interscience) 13 (2): 180–185. doi:10.1002/ana.410130213. ISSN: 0364-5134. PMID 6187275.

- ↑ Donna Wong (2002-03-15). "Notes on Meperidine". Wong on Web Papers. Elsevier. http://www.mosbysdrugconsult.com/WOW/op024.html. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Davis, Sharon (August 2004). "Use of pethidine for pain management in the emergency department: a position statement of the NSW Therapeutic Advisory Group" (PDF). New South Wales Therapeutic Advisory Group. http://www.clininfo.health.nsw.gov.au/nswtag/publications/posstats/Pethidinefinal.pdf. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Latta, Kenneth S.; Brian Ginsberg, Robert L. Barkin (January/February 2002). "Meperidine: A Critical Review". American Journal of Therapeutics (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins) 9 (1): 53–68. doi:10.1097/00045391-200201000-00010. ISSN: 1075-2765. PMID 11782820.

- ↑ Wagner, Larry E., II; Michael Eaton, Salas S. Sabnis, Kevin J. Gingrich (November 1999). "Meperidine and Lidocaine Block of Recombinant Voltage-Dependent Na+ Channels: Evidence that Meperidine is a Local Anesthetic". Anesthesiology (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins) 91 (5): 1481–1490. doi:10.1097/00000542-199911000-00042. ISSN: 0003-3022. PMID 10551601.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Izenwasser, Sari; Amy Hauck Newman, Brian M. Cox, Jonathan L. Katz (January/February 1996). "The cocaine-like behavioral effects of meperidine are mediated by activity at the dopamine transporter". European Journal of Pharmacology (Elsevier) 297 (1-2): 9–17. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(95)00696-6. ISSN: 0014-2999. PMID 8851160.

- ↑ Lomenzo, Stacey A.; Jill B. Rhoden, Sari Izzenwasser, Dean Wade, Theresa Kopajtic, Jonathan L. Katz, Mark L. Trudell (2005-03-05). "Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Meperdine Analogs at Monoamine Transporters". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry (American Chemical Society) 48 (5): 1336–1343. doi:10.1021/jm0401614. ISSN: 0022-2623. PMID 15743177.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Demerol: Is It the Best Analgesic?" (PDF). Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting Service Patient Safety Advisory (Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority) 3 (2). June 2006. http://www.psa.state.pa.us/psa/lib/psa/advisories/v3n2june2006/junevol_3_no_2_article_g_demerol.pdf. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ↑ "In Brief". NPS Radar. National Prescribing Service. December 2005. http://www.nps.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/17273/RADAR_Dec_05_To_print_complete.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ Walker, Diana J.; James P. Zacny (June 1999). "Subjective, Psychomotor, and Physiological Effects of Cumulative Doses of Opioid µ Agonists in Healthy Volunteers". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics) 289 (3): 1454–1464. PMID 10336539.

- ↑ Norpethedine half-life. 2002. Australian prescriber

- ↑ Brody, Jane (February 27, 2007). "A Mix of Medicines That Can Be Lethal". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/27/health/27brody.html?n=Top/News/Health/Diseases,%20Conditions,%20and%20Health%20Topics/Antidepressants. Retrieved 2009-02-13. "The death of Libby Zion, an 18-year-old college student, in a New York hospital on March 5, 1984, led to a highly publicized court battle and created a cause célèbre over the lack of supervision of inexperienced and overworked young doctors. But only much later did experts zero in on the preventable disorder that apparently led to Ms. Zion’s death: a form of drug poisoning called serotonin syndrome."

- ↑ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8 ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 911-914.

- ↑ Package insert for meperidine hydrochloride, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ridgefield, CT, 2005.

- ↑ Gilson AM, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Dahl JL (2004). "A reassessment of trends in the medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics and implications for diversion control: 1997-2002". J Pain Symptom Manage 28 (2): 176–188. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.003. PMID 15276196. http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0885-3924/PIIS0885392404001824.pdf.

- ↑ Joranson DE, Gilson AM (2005). "Drug crime is a source of abused pain medications in the United States". J Pain Symptom Manage 30 (4): 299–301. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.09.001. PMID 16256890. http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0885-3924/PIIS088539240500477X.pdf.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Babor T, et al., compilers (1994). Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9241544686. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241544686.pdf.

|

Opioids |

|

Opium and

Poppy straw

derivatives |

Crude opiate extracts/

whole opium products |

Compote/Kompot/Polish heroin · Diascordium · B & O Supprettes · Dover's powder · Laudanum · Mithridate · Opium · Paregoric · Poppy straw concentrate · Poppy tea · Smoking opium · Theriac

|

|

| Natural Opiates |

Opium Alkaloids

see also: |

|

|

| Alkaloid Salts Mixtures |

Pantopon · Papaveretum (Omnopon) · Tetrapon

|

|

|

| Semisynthetics |

| Morphine Family |

2-(p-Nitrophenyl)-4-isopropylmorphine · 14-Hydroxymorphine · 14β-Hydroxymorphine · 14β-Hydroxymorphone · 2,4-Dinitrophenylmorphine · 6-Methyldihydromorphine · 6-Methylenedihydrodesoxymorphine · 6-Acetyldihydromorphine/6-Monoacetyldihydromorphine · Acetyldihydromorphine · Azidomorphine · Chlornaltrexamine · Dihydrodesoxymorphine (Desomorphine) · Dihydromorphine · Ethyldihydromorphine · Hydromorphinol · Methyldesorphine · N-Phenethylnormorphine · Pseudomorphine · RAM-378

|

|

| 3,6 Diesters of Morphine |

6-acetyl-1-iodocodeine · 6-nicotinoyldihydromorphine · Acetylpropionylmorphine · Acetylbutyrylmorphine · Diacetyldihydromorphine (Dihydroheroin) · Diacetyldibenzoylmorphine · Dibutyrylcodeine · Dibutyrylmorphine · Dibenzoylmorphine · Diformylmorphine · Dipropanoylmorphine · Heroin (Diacetylmorphine) · Nicomorphine · Tetrabenzoylmorphine · Tetrabutyrylmorphine

|

|

| Codeine-Dionine Family |

14-Hydroxydihydrocodeine · Acetylcodeine · Benzylmorphine · Codeine methylbromide · Desocodeine · Dimethylmorphine (Methocodeine) · Dihydroethylmorphine · Methyldihydromorphine (Dihydroheterocodeine) · Ethylmorphine (Dionine) · Heterocodeine · Isocodeine · Isopropylmorphine · Morpholinylethylmorphine (Pholcodine) · Myrophine · Nalodeine · Transisocodeine

|

|

| Morphinones & Morphols |

1-Bromohydrocodone · 1-Bromooxycodone · 1-Chlorohydrocodone · 1-Chlorooxycodone · 1-Iodohydrocodone · 1-Iodooxycodone · 14-Cinnamoyloxycodeinone · 14-Ethoxymetopon · 14-Methoxymetopon · 14β-Hydroxymorphone · 14-O-Methyloxymorphone · 14-Phenylpropoxymetopon · 7-Spiroindanyloxymorphone · 8,14-Dihydroxydihydromorphinone · Acetylcodone · Acetylmorphinol · Acetylmorphone · α-hydrocodol · Bromoisopropropyldihydromorphinone · Codeinone · Codorphone · Codol · Codoxime · Thebacon (Acetyldihydrocodeinone / Dihydrocodeinone enol acetate) · Ethyldihydromorphinone · Hydrocodol · Hydrocodone · Hydromorphinone · Hydromorphol · Hydromorphone · Hydroxycodeine · Isopropropyldihydrocodeinone · Isopropropyldihydromorphinone · Methyldihydromorphinone · Metopon · Morphenol · Morphinol · Morphinone · Morphol · N-Phenethyl-14-ethoxymetopon · Oxycodone · Oxymorphol · Oxymorphinol · Oxymorphone · Pentamorphone · Semorphone

|

|

| Morphides |

α-chlorocodide (Alphachlorocodide/Chlorocodide) · α-chloromorphide · 3-Bromomorphide · Bromocodide · Bromomorphide (8-Bromomorphide) · Chlorocodide · Chloromorphide · · Codide · Fluorocodide (8-Fluorocodide) · Fluormorphide · Iodocodide · Iodomorphide (8-Iodomorphide) · Morphide

|

|

| Dihydrocodeine Series |

14-hydroxydihydrocodeine · Acetyldihydrocodeine · Dihydrocodeine · Dihydrodesoxycodeine/Desocodeine · Dihydroisocodeine · Nicocodeine · Nicodicodeine

|

|

| Nitrogen Morphine Derivatives |

1-Nitrocodeine · 2-Nitrocodeine · 1-Nitromorphine · 2-Nitromorphine · Codeine-N-Oxide · Heroin-N-Oxide · Hydromorphone-N-Oxide · Morphine-N-Oxide

|

|

| Hydrazones |

Acetylmorphazone · Hydromorphazone · Morphazone · Oxymorphazone

|

|

| Halogenated Morphine Derivatives |

1-Bromocodeine · 2-Bromocodeine · 1-Bromodiacetylmorphine · 2-Bromodiacetylmorphine · 1-Bromodihydrocodeine · 2-Bromodihydrocodeine · 1-Bromodihydromorphine · 2-Bromodihydromorphine · 1-Bromomorphine · 2-Bromomorphine · 1-Chlorocodeine · 2-Chlorocodeine · 1-Chlorodiacetylmorphine · 2-Chlorodiacetylmorphine · 1-Chlorodihydrocodeine · 2-Chlorodihydrocodeine · 1-Chlorodihydromorphine · 2-Chlorodihydromorphine · 1-Chloromorphine · 2-Chloromorphine · 1-Fluorocodeine · 2-Fluorocodeine · 1-Fluorodiacetylmorphine · 2-Fluorodiacetylmorphine · 1-Fluorodihydrocodeine · 2-Fluorodihydrocodeine · 1-Fluorodihydromorphine · 2-Fluorodihydromorphine · 1-Fluoromorphine · 2-Fluoromorphine · 3-Fluoromorphine · 1-Iodocodeine · 2-Iodocodeine · 1-Iododiacetylmorphine · 2-Iododiacetylmorphine · 1-Iododihydrocodeine · 2-Iododihydrocodeine · 1-Iododihydromorphine · 2-Iododihydromorphine · 1-Iodomorphine · 2-Iodomorphine · Chlorethylmorphine

|

|

| Others |

|

|

|

Active Opiate

Metabolites |

Codeine-N-Oxide (Genocodeine) · Dihydromorphine-6-glucuronide · Hydromorphone-N-Oxide · Heroin-7,8-Oxide · Morphine-6-glucuronide · 6-Acetylmorphine · Morphine-N-Oxide (Genomorphine) · Naltrexol · Norcodeine · Normorphine

|

|

|

| Morphinans |

| Morphinan Series |

4-chlorophenylpyridomorphinan · Cyclorphan · Dextrallorphan · Dimemorfan · Levargorphan · Levallorphan · Levorphanol · Levorphan · Levophenacylmorphan · Levomethorphan · Norlevorphanol · N-Methylmorphinan · Oxilorphan · Phenomorphan · Methorphan / Racemethorphan · Morphanol / Racemorphanol · Ro4-1539 · Stephodeline · Xorphanol

|

|

| Others |

1-Nitroaknadinine · 14-episinomenine · 5,6-Dihydronorsalutaridine · 6-Ketonalbuphine · Aknadinine · Butorphanol · Cephakicine · Cephasamine · Cyprodime · Drotebanol · Fenfangjine G · Nalbuphine · Sinococuline · Sinomenine (Cocculine) · Tannagine

|

|

|

| Benzomorphans |

5,9-DEHB · Alazocine · Anazocine · Bremazocine · Cogazocine · Cyclazocine · Dezocine · Eptazocine · Etazocine · Ethylketocyclazocine · Fluorophen · Ketazocine · Metazocine · Pentazocine · Phenazocine · Quadazocine · Thiazocine · Tonazocine · Volazocine · Zenazocine

|

|

| 4-Phenylpiperidines |

Pethidines

(Meperidines) |

4-Fluoromeperidine · Allylnorpethidine · Anileridine · Benzethidine · Carperidine · Difenoxin · Diphenoxylate · Etoxeridine (Carbetidine) · Furethidine · Hydroxypethidine (Bemidone) · Hydroxymethoxypethidine · Morpheridine · Oxpheneridine (Carbamethidine) · Meperidine-N-Oxide · Pethidine (Meperidine) · Pethidine Intermediate A · Pethidine Intermediate B (Norpethidine) · Pethidine Intermediate C (Pethidinic Acid) · Pheneridine · Phenoperidine · Piminodine · Properidine (Ipropethidine) · Sameridine

|

|

| Prodines |

Allylprodine · Isopromedol · Meprodine (α-meprodine / β-meprodine) · MPPP (Desmethylprodine) · PEPAP · Prodine (α-prodine / β-prodine) · Prosidol · Trimeperidine (Promedol)

|

|

| Ketobemidones |

Acetoxyketobemidone · Droxypropine · Ketobemidone · Methylketobemidone · Propylketobemidone

|

|

| Others |

Alvimopan · Loperamide · Picenadol

|

|

|

Open Chain

Opioids |

| Amidones |

Dextromethadone · Dextroisomethadone · Dipipanone · Hexalgon (Norpipanone) · Isomethadone · Levoisomethadone · Levomethadone · Methadone · Methadone intermediate · Normethadone · Norpipanone · Phenadoxone (Heptazone) · Pipidone

|

|

| Methadols |

Dimepheptanol (Racemethadol) · Levacetylmethadol · Noracetylmethadol

|

|

| Moramides |

Dextromoramide · Levomoramide · Moramide intermediate · Racemoramide

|

|

| Thiambutenes |

Diethylthiambutene · Dimethylthiambutene · Ethylmethylthiambutene · Piperidylthiambutene · Pyrrolidinylthiambutene · Thiambutene · Tipepidine

|

|

| Phenalkoxams |

|

|

| Ampromides |

Diampromide · Phenampromide · Propiram

|

|

| Others |

IC-26 · Isoaminile · Lefetamine · R-4066

|

|

|

| Anilidopiperidines |

3-Allylfentanyl · 3-Methylfentanyl · 3-Methylthiofentanyl · 4-Phenylfentanyl · Alfentanil · α-methylacetylfentanyl · α-methylfentanyl · α-methylthiofentanyl · Benzylfentanyl · β-hydroxyfentanyl · β-hydroxythiofentanyl · β-methylfentanyl · Brifentanil · Carfentanil · Fentanyl · Lofentanil · Mirfentanil · Ocfentanil · Ohmefentanyl · Parafluorofentanyl · Phenaridine · Remifentanil · Sufentanil · Thenylfentanyl · Thiofentanyl · Trefentanil

|

|

Oripavine

derivatives |

6,14-Endoethenotetrahydrooripavine · 7-PET · Acetorphine · Alletorphine · BU-48 · Buprenorphine · Butorphine · Cyprenorphine · Dihydroetorphine · Diprenorphine (M5050) · Etorphine · 18,19-Dehydrobuprenorphine (HS-599) · N-cyclopropylmethyl-noretorphine · Nepenthone · Norbuprenorphine · Thevinone · Thienorphine

|

|

| Phenazepanes |

Ethoheptazine · Meptazinol · Metheptazine · Metethoheptazine · Proheptazine

|

|

| Pirinitramides |

Bezitramide · Piritramide

|

|

| Benzimidazoles |

Clonitazene · Etonitazene · Nitazene

|

|

| Indoles |

18-MC · 7-Acetoxymitragynine · 7-Hydroxymitragynine · Akuammidine · Akuammine · Eseroline · Hodgkinsine · Ibogaine · Mitragynine · Noribogaine · Pericine · ψ-Akuammigine

|

|

| Diphenylmethylpiperazines |

BW373U86 · DPI-221 · DPI-287 · DPI-3290 · SNC-80

|

|

Opioid peptides

see also: The Opioid Peptides |

Adrenorphin · Amidorphin · Casomorphin · DADLE · DALDA · DAMGO · Dermenkephalin · Dermorphin · Deltorphin · DPDPE · Dynorphin · Endomorphin · Endorphin · Enkephalin · Gliadorphin · Morphiceptin · Nociceptin · Octreotide · Opiorphin · Rubiscolin · TRIMU 5

|

|

| Others |

3-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-3-ethoxycarbonyltropane · AH-7921 • Azaprocin · BDPC · Bisnortilidine · BRL-52537 · Bromadoline • C-8813 · Ciramadol · Doxpicomine • Enadoline · Esketamine · Faxeladol · GR-89696 · Herkinorin · ICI-199,441 · ICI-204,448 · J-113,397 · JTC-801 · Ketamine · LPK-26 · Methopholine · Methoxetamine · N-Desmethylclozapine · NNC 63-0532 · Nortilidine · O-Desmethyltramadol · Phenadone · Phencyclidine · Prodilidine · Profadol · Ro64-6198 · Salvinorin A · SB-612,111 · SC-17599 · RWJ-394,674 · TAN-67 · Tapentadol · Tecodine · Tifluadom · Tilidine · Tramadol · Trimebutine · U-50,488 · U-69,593 · Viminol · W-18 ·

|

|

Opioid Antagonists

&

Inverse-Agonists |

5'-Guanidinonaltrindole · β-Funaltrexamine · 6β-Naltrexol · Alvimopan · Amiphenazole · Binaltorphimine · Chlornaltrexamine · Clocinnamox · Cyclazocine · Cyprodime · Diprenorphine (M5050) · Fedotozine · JDTic · Levallorphan · Methocinnamox · Methylnaltrexone · Nalfurafine · Nalmefene · Nalmexone · Naloxazone · Naloxonazine · Naloxone · Naloxone benzoylhydrazone · Nalorphine · Naltrexone · Naltriben · Naltrindole · Norbinaltorphimine · Oxilorphan · S-allyl-3-hydroxy-17-thioniamorphinan (SAHTM)

|

|

|

Analgesics (N02A, N02B) |

|

Opioids

See also: Opioids template |

|

Opium & alkaloids thereof

|

|

|

|

Semi-synthetic opium

derivatives

|

|

|

|

Synthetic opioids

|

Alphaprodine · Anileridine · Butorphanol · Dextromoramide · Dextropropoxyphene · Dezocine · Fentanyl · Ketobemidone · Levorphanol · Methadone · Meptazinol · Nalbuphine · Pentazocine · Propoxyphene · Propiram · Pethidine · Phenazocine · Piminodine · Piritramide · Tapentadol · Tilidine · Tramadol

|

|

|

| Pyrazolones |

Ampyrone/Aminophenazone · Metamizole · Phenazone · Propyphenazone

|

|

| Cannabinoids |

|

|

| Anilides |

|

|

Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatories

See also: NSAIDs template |

|

Propionic acid class

|

Fenoprofen · Flurbiprofen · Ibuprofen · Ketoprofen · Naproxen · Oxaprozin

|

|

|

Oxicam class

|

|

|

|

Acetic acid class

|

|

|

|

COX-2 inhibitors

|

Celecoxib · Rofecoxib · Valdecoxib · Parecoxib · Lumiracoxib

|

|

|

Anthranilic acid

(fenamate) class

|

Meclofenamate · Mefenamic acid

|

|

|

|

Aspirin (Acetylsalicylic acid) · Benorylate · Diflunisal · Ethenzamide · Magnesium salicylate · Salicin · Salicylamide · Salsalate · Trisalate · Wintergreen (Methyl salicylate)

|

|

|

Atypical, Adjuvant & Potentiators,

Metabolic agents and miscellaneous |

|

|

|

|

anat(s,m,p,,e,b,d,c,,f,,g)/phys/devp/cell

|

noco(m,d,e,h,v,s)/cong/tumr,sysi/,injr

|

proc,drug(N1A/2AB/C/3/4/7A/B//)

|

|

|

|

|

Serotonergics |

|

|

5-HT1 receptor ligands |

|

|

5-HT1A

|

Agonists: Azapirones: Alnespirone • Binospirone • Buspirone • Enilospirone • Eptapirone • Gepirone • Ipsapirone • Perospirone • Revospirone • Tandospirone • Tiospirone • Umespirone • Zalospirone; Antidepressants: Etoperidone • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Quetiapine • Ziprasidone; Ergolines: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • Methysergide • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • DMT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • Adatanserin • Befiradol • BMY-14802 • Cannabidiol • Dimemebfe • Ebalzotan • Eltoprazine • F-11,461 • F-12,826 • F-13,714 • F-14,679 • F-15,063 • F-15,599 • Flesinoxan • Flibanserin • Lesopitron • Lu AA21004 • LY-293,284 • LY-301,317 • MKC-242 • NBUMP • Osemozotan • Oxaflozane • Pardoprunox • Piclozotan • Rauwolscine • Repinotan • Roxindole • RU-24,969 • S 14,506 • S-14,671 • S-15,535 • Sarizotan • SSR-181,507 • Sunepitron • U-92016A • Urapidil • Vilazodone • Xaliproden • Yohimbine

Antagonists: Antipsychotics: Iloperidone • Risperidone • Sertindole; Beta blockers: Alprenolol • Cyanopindolol • Iodocyanopindolol • Oxprenolol • Pindobind • Pindolol • Propranolol • Tertatolol; Others: AV965 • BMY-7378 • CSP-2503 • Dotarizine • Flopropione • GR-46611 • Isamoltane • Lecozotan • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MPPF • NAN-190 • PRX-00023 • Robalzotan • S-15535 • SB-649915 • SDZ 216-525 • Spiperone • Spiramide • Spiroxatrine • UH-301 • WAY-100,135 • WAY-100,635 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

5-HT1B

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Methysergide; Piperazines: Eltoprazine • TFMPP; Triptans: Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CGS-12066A • CP-93,129 • CP-94,253 • CP-135,807 • RU-24969

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: AR-A000002 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Isamoltane • Metitepine/Methiothepin • SB-216,641 • SB-224,289 • SB-236,057 • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT1D

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Methysergide; Triptans: Almotriptan • Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Frovatriptan • Naratriptan • Rizatriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CP-135,807 • CP-286,601 • GR-46611 • L-694,247 • L-772,405 • PNU-109,291 • PNU-142,633

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: Alniditan • BRL-15572 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Ketanserin • LY-310,762 • LY-367,642 • LY-456,219 • LY-456,220 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • Yohimbine • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

5-HT1E

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Methysergide; Triptans: Eletriptan; Tryptamines: BRL-54443 • Tryptamine

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

5-HT1F

|

Agonists: Triptans: Eletriptan • Naratriptan • Sumatriptan; Tryptamines: 5-MT; Others: BRL-54443 • Lasmiditan • LY-334,370

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT2 receptor ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT2A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: ALD-52 • Ergonovine • Lisuride • LA-SS-Az • LSD • LSD-Pip • Lysergic acid 2-butyl amide • Methysergide; Phenethylamines: 25I-NBMD • 25I-NBOH • 25I-NBOMe • 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2CB-Ind • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • 2CBCB-NBOMe • 2CBFly-NBOMe • Bromo-DragonFLY • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline • TCB-2 • TFMFly; Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: AL-34662 • AL-37350A • Dimemebfe • Medifoxamine • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • RH-34

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Amperozide • Aripiprazole • Carpipramine • Clocapramine • Clozapine • Gevotroline • Iloperidone • Melperone • Mosapramine • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Others: 5-I-R91150 • AC-90179 • Adatanserin • Altanserin • AMDA • APD-215 • Blonanserin • Cinanserin • CSP-2503 • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eplivanserin • Esmirtazapine • Fananserin • Flibanserin • Ketanserin • KML-010 • Lubazodone • Mepiprazole • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Nantenine • Pimavanserin • Pizotifen • Pruvanserin • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • S-14,671 • Sarpogrelate • Setoperone • Spiperone • Spiramide • SR-46349B • Volinanserin • Xylamidine • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2B

|

Agonists: Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex; Phenethylamines: Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • Fenfluramine • MDA • MDMA • Norfenfluramine; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • α-Methyl-5-HT; Others: BW-723C86 • Cabergoline • mCPP • Pergolide • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175

Antagonists: Agomelatine • Asenapine • EGIS-7625 • Ketanserin • Lisuride • LY-272,015 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • PRX-08066 • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • RS-127,445 • Sarpogrelate • SB-200,646 • SB-204,741 • SB-206,553 • SB-215,505 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SDZ SER-082 • Tegaserod • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2C

|

Agonists: Phenethylamines: 2C-B • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline; Piperazines: Aripiprazole • mCPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: A-372,159 • AL-38022A • CP-809,101 • Dimemebfe • Lorcaserin• Medifoxamine • MK-212 • ORG-37,684 • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175 • Vabicaserin • WAY-629 • WAY-161,503 • YM-348

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Iloperidone • Melperone • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Agomelatine • Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Fluoxetine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Nortriptyline • Trazodone; Others: Adatanserin • Cinanserin • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eltoprazine • Esmirtazapine • FR-260,010 • Ketanserin • Ketotifen • Latrepirdine • Lu AA24530 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Methysergide • Pizotifen • Ritanserin • RS-102,221 • S-14,671 • SB-200,646 • SB-206,553 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SB-242,084 • SB-243,213 • SDZ SER-082 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT3

|

Agonists: Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-CT; Others: Chlorophenylbiguanide • Butanol • Ethanol • Halothane • Isoflurane • RS-56812 • SR-57,227 • SR-57,227-A • Toluene • Trichloroethane • Trichloroethanol • Trichloroethylene • YM-31636

Antagonists: Antiemetics: AS-8112 • Alosetron • Azasetron • Batanopride • Bemesetron • Cilansetron • Dazopride • Dolasetron • Granisetron • Lerisetron • Ondansetron • Palonosetron • Ramosetron • Renzapride • Tropisetron • Zacopride • Zatosetron; Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Olanzapine • Quetiapine; Tetracyclic antidepressants: Amoxapine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine; Others: CSP-2503 • ICS-205,930 • Lu AA21004 • Lu AA24530 • MDL-72,222 • Memantine • Nitrous Oxide • Ricasetron • Sevoflurane • Thujone • Xenon

|

|

|

5-HT4

|

Agonists: Gastroprokinetic Agents: Cinitapride • Cisapride • Dazopride • Metoclopramide • Mosapride • Prucalopride • Renzapride • Tegaserod • Zacopride; Others: 5-MT • BIMU-8 • CJ-033,466 • PRX-03140 • RS-67333 • RS-67506 • SL65.0155 • TD-5108

Antagonists: GR-113,808 • GR-125,487 • L-Lysine • Piboserod • RS-39604 • RS-67532 • SB-203,186

|

|

|

5-HT5A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Ergotamine • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT; Others: Valerenic Acid

Antagonists: Asenapine • Latrepirdine • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • SB-699,551

* Note that the 5-HT5B receptor is not functional in humans.

|

|

|

5-HT6

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • LSD • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-BT • 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • E-6801 • E-6837 • EMD-386,088 • EMDT • LY-586,713 • N-Methyl-5-HT • Tryptamine; Others: WAY-181,187 • WAY-208,466

Antagonists: Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Doxepin • Mianserin • Nortriptyline; Atypical antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Fluperlapine • Iloperidone • Olanzapine • Tiospirone; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: BGC20-760 • BVT-5182 • BVT-74316 • EGIS-12233 • GW-742,457 • Ketanserin • Latrepirdine • Lu AE58054 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MS-245 • PRX-07034 • Ritanserin • Ro 04-6790 • Ro 63-0563 • SB-258,585 • SB-271,046 • SB-357,134 • SB-399,885 • SB-742,457

|

|

|

5-HT7

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • AS-19 • Bifeprunox • LP-12 • LP-44 • RU-24,969 • Sarizotan

Antagonists: Lysergamides: 2-Bromo-LSD • Bromocriptine • Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Imipramine • Maprotiline • Mianserin; Atypical antipsychotics: Amisulpride • Aripiprazole • Clozapine • Olanzapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Tiospirone • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: Butaclamol • EGIS-12233 • Ketanserin • LY-215,840 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Pimozide • Ritanserin • SB-258,719 • SB-258,741 • SB-269,970 • SB-656,104 • SB-656,104-A • SB-691,673 • SLV-313 • SLV-314 • Spiperone • SSR-181,507

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

SERT

|

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Alaproclate • Citalopram • Dapoxetine • Desmethylcitalopram • Desmethylsertraline • Escitalopram • Femoxetine • Fluoxetine • Fluvoxamine • Indalpine • Ifoxetine • Litoxetine • Lu AA21004 • Lubazodone • Panuramine • Paroxetine • Pirandamine • RTI-353 • Seproxetine • Sertraline • Vilazodone • Zimelidine; Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Bicifadine • Desvenlafaxine • Duloxetine • Eclanamine • Levomilnacipran • Milnacipran • Sibutramine • Venlafaxine; Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (SNDRIs): Brasofensine • Diclofensine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • NS-2359 • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Tesofensine; Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): Amitriptyline • Butriptyline • Cianopramine • Clomipramine • Desipramine • Dosulepin • Doxepin • Imipramine • Lofepramine • Nortriptyline • Pipofezine • Protriptyline • Trimipramine; Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs): Amoxapine; Piperazines: Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antihistamines: Brompheniramine • Chlorpheniramine • Diphenhydramine • Mepyramine/Pyrilamine • Pheniramine • Tripelennamine; Opioids: Meperidine (Pethidine) • Methadone • Propoxyphene; Others: Cocaine • CP-39,332 • Cyclobenzaprine • Dextromethorphan • Dextrorphan • EXP-561 • Fezolamine • Mesembrine • Nefopam • PIM-35 • Pridefrine • Roxindole • SB-649,915 • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

VMAT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Aminoindanes: 5-IAI • ETAI • MDAI • MDMAI • MMAI • TAI; Aminotetralins: 6-CAT • 8-OH-DPAT • MDAT • MDMAT; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex • Clominorex • Fluminorex; Phenethylamines (also Amphetamines, Cathinones, Phentermines, etc): 2-Methyl-MDA • 4-CAB • 4-FA • 4-FMA • 4-HA • 4-MTA • 5-APDB • 5-Methyl-MDA • 6-APDB • 6-Methyl-MDA • Amiflamine • BDB • BOH • Brephedrone • Butylone • Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • Diethylcathinone • Dimethylcathinone • DMA • DMMA • EBDB • EDMA • Ethylone • Etolorex • Fenfluramine (Dexfenfluramine) • Flephedrone • IAP • IMP • Lophophine • MBDB • MDA • MDEA • MDHMA • MDMA • MDMPEA • MDOH • MDPEA • Mephedrone • Methedrone • Methylone • MMA • MMDA • MMDMA • NAP • Norfenfluramine • pBA • pCA • pIA • PMA • PMEA • PMMA • TAP; Piperazines: 2C-B-BZP • BZP • MBZP • mCPP • MDBZP • MeOPP • Mepiprazole • pFPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 4-Methyl-αET • 4-Methyl-αMT • 5-CT • 5-MeO-αET • 5-MeO-αMT • 5-MT • αET • αMT • DMT • Tryptamine (itself); Others: Indeloxazine • Tramadol • Viqualine

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

TPH

|

AGN-2979 • Fenclonine

|

|

|

AAAD

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

|

|

|

MAO

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A Selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity enhancers: BPAP • PPAP; Reuptake enhancers: Tianeptine

|

|

|

|