The Decameron

The Decameron (subtitle: Prencipe Galeotto) is a collection of 100 novellas by Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio, probably begun in 1350 and finished in 1353. It is a medieval allegorical work best known for its bawdy tales of love, appearing in all its possibilities from the erotic to the tragic. Some believe many parts of the tales are indebted to the influence of The Book of Good Love. Many notable writers, such as Geoffrey Chaucer, are said to have drawn inspiration from The Decameron (See Literary sources and influence of the Decameron below).

The title is a portmanteau of two Greek words meaning "ten" (δέκα déka) and "day" (ἡμέρα hēméra).[1]

Contents |

Description

The Decameron is structured in a frame narrative, or frame tale. The Decameron played a part in the history of the novel and was finished by Giovanni Boccaccio in 1351. It opens with a description of the Bubonic Plague (Black Death) and leads into an introduction of a group of seven young women and three young men who fled from plague-ridden Florence for a villa outside of the city walls. To pass the time, each member of the party tells one story for every one of the ten nights spent at the villa. The Decameron is a distinctive work, in that it describes in detail the physical, psychological and social effects that the Bubonic Plague had on that part of Europe. While a number of the stories contained within the Decameron would later appear in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, it is not clear whether Chaucer knew of the Decameron.

One of the women, Pampinea, is elected Queen for the first day. Each day the company's previous king/queen elects who shall succeed them and nominates the theme for the current day's storytelling. Each day has a new theme assigned to it except for days 1 and 9: misfortunes that bring a person to a state of unexpected happiness; people who have achieved an object they greatly desired, or recovered a thing previously lost; love stories that ended unhappily; love that survived disaster; those who have avoided danger; tricks women have played on their husbands; tricks both men and women play on each other; those who have given very generously whether for love or another endeavor. Dioneo, who always speaks last, doesn't have to conform to the day's theme; the girls like his tales, which are full of jest, but they find that his sense of humor is sometimes immodest.

The subtitle is Prencipe Galeotto, which derives from the opening material in which Boccaccio dedicates the work to ladies of the day who did not have the diversions of men (hunting, fishing, riding, falconry) who were forced to conceal their amorous passions and stay idle and concealed in their rooms. Thus the book is subtitled Prencipe Galeotto, that is Galehaut, the go-between of Lancelot and Guinevere, a nod to Dante's allusion to Galeotto in "Inferno V", who was blamed for the arousal of lust in the episode of Paolo and Francesca.

Boccaccio gives introductions and conclusions to each story which describe the days activities before and after the story-telling. These inserts frequently include transcriptions of Italian folk songs. From the interactions among tales told within a day (or across multiple days), Boccaccio spins variations and reversals of previous material to form a cohesive whole which is more than just a collection of stories.

Analysis

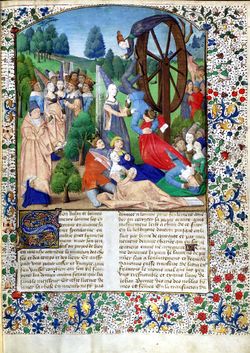

Beyond the unity provided by the frame narrative, Decameron provides a unity in philosophical outlook. Throughout runs the common medieval theme of Lady Fortune, and how quickly one can rise and fall through the external influences of the "Wheel of Fortune". Boccaccio had been educated in the tradition of Dante's Divine Comedy which used various levels of allegory to show the connections between the literal events of the story and the Christian message. However, Decameron uses Dante's model not to educate the reader but to satirize this method of learning. The Roman Catholic Church, priests, and religious belief become the satirical source of comedy throughout. This was part of a wider historical trend in the aftermath of the Black Death which saw widespread discontent with the church.

Many details of the Decameron are infused with a medieval sense of numerological and mystical significance. For example, it is widely believed that the seven young women are meant to represent the Four Cardinal Virtues (Prudence, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude) and the Three Theological Virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity). It is further supposed that the three men represent the classical Greek tripartite division of the soul (Reason, Spirit, and Lust, see Book IV of Republic). Boccaccio himself notes that the names he gives for these ten characters are in fact pseudonyms chosen as "appropriate to the qualities of each". The Italian names of the seven women, in the same (most likely significant) order as given in the text, are: Pampinea (the flourishing one), Fiammetta (small flame), Filomena (faithful in love), Emilia (rival), Lauretta (wise, crowned with laurels), Neifile (cloudy), and Elissa (God is my vow).

The men, in order, are: Panfilo (completely in love), Filostrato (overcome by love), and Dioneo (lustful).[2]

Literary sources and influence of the Decameron

The compelling way in which the tales were written and their almost exclusively Renaissance flair made the stories from the Decameron an irresistible source that many later writers borrowed from. Notable examples include:

- The famous first tale (I, 1) of the notorious Ser Ciappelletto was later translated into Latin by Olimpia Fulvia Morata and translated again by Voltaire.

- Martin Luther retells tale I, 2, in which a Jew converts to Catholicism after visiting Rome and seeing the corruption of the Catholic hierarchy. However, in Luther's version (found in his "Table-talk #1899"), Luther and Philipp Melanchthon try to dissuade the Jew from visiting Rome.

- Marguerite de Navarre, Heptaméron.

- The ring parable is at the heart of both Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's 1779 play Nathan the Wise and tale I, 3. In a letter to his brother on August 11, 1778, he says explicitly that he got the story from the Decameron. Jonathan Swift also used the same story for his first major published work, A Tale of a Tub.

- Posthumus's wager on Imogen's chastity in Cymbeline was taken by Shakespeare from an English translation of a fifteenth century German tale, "Frederyke of Jennen", whose basic plot came from tale II, 9.

- Both Molière and Lope de Vega use tale III, 3 to create plays in their respective vernaculars. Molière wrote L'école des maris in 1661 and Lope de Vega wrote Discreta enamorada.

- Tale III, 9, which Shakespeare converted into All's Well That Ends Well. Shakespeare probably first read a French translation of the tale in William Painter's Palace of Pleasure.

- Tale IV, 1 was reabsorbed into folklore to appear as Child ballad 269, Lady Diamond.[3]

- John Keats borrowed the tale of Lisabetta and her pot of basil (IV, 5) for his poem, Isabella, or the Pot of Basil.

- Lope de Vega also used parts of V, 4 for his play No son todos ruiseñores (They're Not All Nightingales).

- Christoph Martin Wieland's set of six novellas Das Hexameron von Rosenhain is based on the structure of the Decameron.

- The title character in George Eliot's historical novel Romola emulates Gostanza in tale V, 2, by buying a small boat and drifting out to sea to die, after she realizes that she no longer has anyone on whom she can depend.

- Tale V, 9 became the source for works by two famous nineteenth century writers in the English language. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow used it in his "The Falcon of Ser Federigo" as part of Tales of a Wayside Inn in 1863. Alfred, Lord Tennyson used it in 1879 for a play entitled The Falcon.

- Molière also borrowed from tale VII, 4 in his George Dandin, ou le Mari Confondu (The Confounded Husband). In both stories the husband is convinced that he has accidentally caused his wife's suicide.

- The motif of the three trunks in The Merchant of Venice by Shakespeare is found in tale X, 1. However, both Shakespeare and Boccaccio probably came upon the tale in Gesta Romanorum.

- At his death Percy Bysshe Shelley had left a fragment of a poem entitled "Ginevra", which he took from the first volume of an Italian book called L'Osservatore Fiorentino. The earlier Italian text had a plot taken from tale X, 4.

- Tale X, 5 shares its plot with Chaucer's "The Franklin's Tale", although this is not due to a direct borrowing from Boccaccio. Rather, both authors used a common French source.

- The tale of patient Griselda (X, 10) was the source of Chaucer's "The Clerk's Tale." However, there are some scholars that believe Chaucer may not have been directly familiar with the Decameron, and instead derived it from a Latin translation/retelling of that tale by Petrarch.

- Christine De Pizan often restructures tales from Decameron in her work "The Book of the City of Ladies"

- Tzvetan Todorov used the Decameron as the basis for The Grammar of the Decameron (1969), an exploration of the general structure of all narrative.

- In the '60s, Hugh Hefner tried to adapt the bawdier stories from the Decameron into full-fledged pornography.

- The Charles Bukowski Novel Women (1978) was inspired by The Decameron.

- Paul Calandrino's play The Nincompoop (2007) casts Calandrino in a new tale in which the simpleton is inspired to paint the ceiling of his local church while Bruno and Buffalmacco plot new ways to humiliate him.

- Steven James's mystery thriller novel The Knight (2009) depicts a serial killer who bases his murders off tales told in day four of The Decameron.

Boccaccio, in turn, borrowed the plots of almost all of his stories. Although he only consulted French, Italian, and Latin sources, some of the tales have their ultimate origin in such far-off lands as India, Persia, Spain, and other places. Moreover, some were already centuries old. For example, part of the tale of Andreuccio of Perugia (II, 5) originated in second century Ephesus (in the Ephesian Tale). The frame narrative structure (though not the characters or plot) originates from the Panchatantra, which was written in Sanskrit before 500 AD and came to Boccaccio through a chain of translations that includes Old Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin. Even the description of the central current event of the narrative, the Black Plague (which Boccaccio surely witnessed), is not original, but based on the Historia gentis Langobardorum of Paul the Deacon, who lived in the eighth century.

Some scholars have suggested that some of the tales for which there is no prior source may still have not have been invented by Boccaccio, but may have been circulating in the local oral tradition and Boccaccio may have just happened to be the first person that we know of to record them. Boccaccio himself says that he heard some of the tales orally. In VII, 1, for example, he claims to have heard the tale from an old woman who heard it as a child.

However, just because Boccaccio borrowed the storylines that make up most of the Decameron doesn't mean he mechanically reproduced them. Most of the stories take place in the fourteenth century and have been sufficiently updated for the author's time that a reader may not know that they had been written centuries earlier or in a foreign culture. Also, Boccaccio often combined two or more unrelated tales into one (such as in II, 2 and VII, 7).

Moreover, many of the characters actually existed, such as Giotto di Bondone, Guido Cavalcanti, Saladin and King William II of Sicily. Scholars have even been able to verify the existence of less famous characters, such as the tricksters Bruno and Buffalmacco and their victim Calandrino. Still other fictional characters are based on real people, such as the Madonna Fiordaliso from tale II, 5, who is derived from a Madonna Flora that lived in the red light district of Naples. Boccaccio often intentionally muddled historical (II, 3) and geographical (V, 2) facts for his narrative purposes. Within the tales of the Decameron the principal characters are usually developed through their dialogue and actions so that by the end of the story they seem real and their actions logical given their context.

Another of Boccaccio's frequent techniques was to make already existing tales more complex. A clear example of this is in tale IX, 6, which was also used by Chaucer in his "The Reeve's Tale", but more closely follows the original French source than does Boccaccio's version. In the Italian version the host's wife (in addition to the two young male visitors) occupy all three beds and she also creates an explanation of the happenings of the evening. Both elements are Boccaccio's invention and make for a more complex version than either Chaucer's version or the French source (a fabliau by Jean de Boves).

Film adaptations

A number of film adaptations have been based on tales from The Decameron. Pier Paolo Pasolini's Decameron made in 1971 is one of the most famous. Decameron Nights, released in 1953, was based on three of the tales and starred Louis Jourdan as Boccaccio. Virgin Territory, an R-rated comedy film, was produced by Dino De Laurentiis in 2007.

Boccaccio's drawings

Since The Decameron was very popular among contemporaries, especially merchants, there is an enormous quantity of ancient manuscripts of it. The Italian philologist Vittore Branca did a comprehensive survey of them and identified a few copied under Boccaccio's supervision; some have notes written in Boccaccio's hand. Two in particular have elaborate drawings, probably done by Boccaccio himself. Since these manuscripts were widely circulated, Branca thought that they influenced all subsequent illustrations.

See also

- Summary of Decameron tales for a detailed description.

- Cent Nouvelles nouvelles

References

- ↑ The Greek title would be δεκάμερον (τό), with a more correct classical Greek compound being δεχήμερον

- ↑ Boccaccio, Giovanni. The Decameron. Trans. Mark Musa and Thomas G. Bergin. New York: Signet Classic, 2002. (page 19).

- ↑ Helen Child Sargent, ed; George Lymn Kittredge, ed English and Scottish Popular Ballads: Cambridge Edition p 583 Houghton Mifflin Company Boston 1904

External links

- Decameron Web, from Brown University

- The Decameron - Introduction, from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- 'The Enchanted Garden', a painting by John William Waterhouse

- The Decameron, Volume I at Project Gutenberg (Rigg translation)

- The Decameron, Volume II at Project Gutenberg (Rigg translation)

- The Decameron at Project Gutenberg (Payne translation)

- Concordances of Decameron

- Decameron English and Italian text for a direct comparison

- from Decameron - Federigo degli Alberighi (9th novel) on audio mp3- free download (in Italian & English)