Daguerreotype

The daguerreotype (original French: daguerréotype) was the first successful photographic process.

It was developed by Louis Daguerre together with Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Niepce had produced the first photographic image in the camera obscura using asphaltum on a copper plate sensitised with lavender oil that required very long exposures.

The image in a Daguerreotype is formed by the amalgam, or combination, of mercury and silver. Mercury vapor from a pool of heated mercury is used to develop the plate that consists of a copper plate with a thin coating of silver rolled in contact that has previously been sensitised to light with iodine vapour so as to form silver iodide crystals on the silver surface of the plate.

Exposure times were later reduced by using bromine to form silver bromide crystals, and by replacing the Chevalier lenses with much larger, faster lenses designed by Joseph Petzval.

The image is formed on the surface of the silver plate that looks like a mirror. It can easily be rubbed off with the fingers and will oxidise in the air, so from the outset daguerreotypes were mounted in sealed cases or frames with a glass cover.

When viewing the daguerreotype, a dark surface is reflected into the mirrored silver surface, and the reproduction of detail in sharp photographs is very good, partly because of the perfectly flat surface.

Although daguerreotypes are unique images, they could be copied by redaguerreotyping the original.[2]

Contents |

Invention

Artists and inventors, since the late Renaissance, had been looking for a mechanical method of capturing visual scenes.[1] Previously, using camera obscura, artists would manually trace what they saw.

Previous discoveries of photosensitive methods and substances—including silver nitrate by Albertus Magnus in the 1200s,[3] a silver and chalk mixture by Johann Heinrich Schulze in 1724, and Nicéphore Niépce’s bitumen-based heliography[1] in 1822[4] —contributed to development of the daguerreotype. In 1829 French artist and chemist Louis J.M. Daguerre, contributing a cutting edge camera design, partnered with Niépce, a leader in photochemistry, to further develop their technologies.[1]

After Niépce’s 1833 death, Daguerre continued to research the chemistry and mechanics of recording images by coating copper plates with iodized silver.[1] in 1835 Daguerre discovered—after accidentally breaking a mercury thermometer—a method of developing images that had been exposed for 20–30 minutes.[1] Further refinement of his process would allow him to fix the image—preventing further darkening of the silver—using a strong solution of common salts. The 1837 still life of plaster casts, a wicker-covered bottle, a framed drawing and a curtain—titled L’Atelier de l'artiste—was his first daguerreotype to successfully undergo the full process of exposure, development and fixation.[1]

The French Academy of Sciences announced the daguerreotype process on January 9, 1839. Later that year William Fox Talbot announced his calotype. Together, these inventions mark 1839 as the year photography was invented.[5]

Instead of Daguerre obtaining a French patent, the French government provided a pension for him.[6] In Britain, Miles Berry, acting on Daguerre's behalf, obtained a patent for the daguerreotype process on August 14, 1839. Almost simultaneously, on August 19, 1839, the French government announced the invention as a gift “Free to the World.”

Daguerreotype process

The daguerreotype, along with the Tintype, is a photographic image allowing no direct transfer of the image onto another light-sensitive medium, as opposed to glass plate or paper negatives. Preparation of the plate prior to image exposure resulted in the formation of a layer of photo-sensitive silver halide, and exposure to a scene or image through a lens formed a latent image. The latent image was made visible, or "developed", by placing the exposed plate over a slightly heated (about 30°C / 90°F) cup of mercury. Daguerre was first to discover and publish (in the publication of the process and the English patent of 1839) the principle of latent image development.

The mercury vapour condensed on those places on the plate where the exposure light was most intense (highlights), and less so in darker areas of the image (shadows). This produced a picture in an amalgam, the mercury washing the silver out of the halides, solubilizing and amalgamating it into free silver particles which adhered to the exposed areas of the plate, leaving the unexposed silver halide ready to be removed by the fixing process. This resulted in the final unfixed image, which consisted of light and dark areas of grey amalgam on the plate. The developing box was constructed to allow inspection of the image through a yellow glass window to allow the photographer to determine when to stop development.

The next operation was to "fix" the photographic image permanently on the plate by dipping in a solution of hyposulphite of soda, often called "fixer" or "hypo", to dissolve the unexposed halides. Initially, Daguerre's process was to use a saturated salt solution for this step, but later adopted Hershel's suggestion of Sodium thiosulphate, as did W. H. F. Talbot.

The image produced by this method is extremely fragile and susceptible to damage when handled. Practically all daguerreotypes are protected from accidental damage by a glass-fronted enclosure. It was discovered by experiment that treating the plate with heated gold chloride both tones and strengthens the image, although it remains quite delicate and requires a well-sealed enclosure to protect against touch as well as oxidation of the fine silver deposits forming the blacks in the image. The best-preserved daguerreotypes dating from the nineteenth century are sealed in robust glass cases evacuated of air and filled with a chemically inert gas, typically nitrogen.

Proliferation

André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri[7] and Jules Itier[8] in France, and Johann Baptist Isenring[9] in Switzerland, became prominent daguerreotypists. In the United Kingdom, however, Richard Beard bought the British daguerreotype patent from Miles Berry in 1841 and closely controlled his investment, selling licenses throughout the country and prosecuting infringers.[10] Among others, Antoine Claudet[11] and Thomas Richard Williams[12] produced daguerreotypes in the U.K.

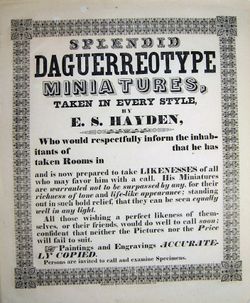

Daguerreotype photography spread rapidly across the United States. In the early 1840s, the invention was introduced in a period of months to practitioners in the United States by Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph code. One of these original Morse Daguerreotype cameras is currently on display at the National Museum of American History, a branch of the Smithsonian, in Washington, DC.[5] A flourishing market in portraiture sprang up, predominantly the work of itinerant practitioners who traveled from town to town. For the first time in history, people could obtain an exact likeness of themselves or their loved ones for a modest cost, making portrait photographs extremely popular with those of modest means. Notable U.S. daguerreotypists of the mid-1800s included James Presley Ball,[13] Samuel Bemis,[14] Abraham Bogardus,[14] Mathew Brady,[15] Thomas Martin Easterly,[16] Jeremiah Gurney,[17] John Plumbe, Jr.,[18] Albert Southworth,[19] Augustus Washington,[20] Ezra Greenleaf Weld,[21] and John Adams Whipple.[14]

This method spread to other parts of the world as well. In 1857, Ichiki Shirō created the first known Japanese photograph, a portrait of his daimyo Shimazu Nariakira. This photograph was designated an Important Cultural Property by the government of Japan.

The daguerreotype is commonly, erroneously, believed to have been the dominant photographic process into the late part of the 19th century in Europe. Evidence from the period proves it was only in widespread use for approximately a decade before being superseded by other processes:

- The calotype, introduced in 1841; a negative-positive process using a paper negative.

- The collodion wet plate process, introduced in 1851; a negative-positive process using silver salt impregnated collodion poured from a bottle onto a glass plate.

The collodion wet plate process was used to produce ambrotypes on glass and tintypes or ferrotypes on a coated iron plate.

- The ambrotype, introduced in 1854; a positive-appearing negative image on glass with a black paper backing.

- The tintype or ferrotype, introduced in 1856; a positive-appearing negative image on an opaque metal plate.

Demise

The intricate, complex, labor-intensive daguerreotype process itself helped contribute to the rapid move to the ambrotype and tintype. The proliferation of these simpler and much less expensive photographic processes made the costly daguerreotypes less appealing to the average person (although it remained very popular in astronomical observatories until the invention of glass plate cameras). According to Mace (1999), the rigidity of these images stems more from the seriousness of the activity than a long exposure time, which he says was actually only a few seconds (Early Photographs, p. 21). The daguerreotype's lack of a negative image from which multiple positive "prints" could be made was a limitation also shared by the tintype, but was not a factor in the daguerreotype's demise until the introduction of the calotype. The fact that many of those to use the process suffered severe health problems or even death from mercury poisoning after inhaling toxic vapors created during the heating process also contributed to its falling out of favor with photographers.[22] Unlike film and paper photography however, a properly sealed daguerreotype can potentially last indefinitely.

In May 2007, an anonymous buyer paid 576,000 euros (~775,000 USD) for an original 1839 camera made by Susse Frères (Susse brothers), Paris, at an auction in Vienna, Austria, making it the world's oldest and most expensive commercial photographic apparatus.[23]

The daguerreotype's popularity was not threatened until photography was used to make imitation daguerreotypes on glass positives called ambrotypes, meaning "imperishable picture" (Newhall, 107).[14]

Value in the marketplace

Some daguerreotypes which have maker's marks, such as those by Southworth & Hawes of Boston, or George S. Cook of Charleston, South Carolina, Gurney, Pratt and others, are considered masterpieces in the art of photography. A daguerreotype of Edgar Allan Poe was featured on the PBS show Antiques Roadshow and appraised at US $30,000 to $50,000. In 2006 Sotheby's sold a different daguerreotype of Poe for $150,000. The image was taken by William Abbott Pratt two weeks shy of Poe's 1849 death.[24]

Modern daguerreotype

Daguerreotype continues to be practiced by enthusiastic photographers to this day, although in much smaller numbers; there are thought to be fewer than 100 worldwide (see list of artists on cdags.org in links below). In recent years artists like Jerry Spagnoli, Adam Fuss, and Chuck Close have re-introduced the medium to the broader art world. Its appeal lies in the "magic mirror" effect of light reflected from the polished silver plate through the perfectly sharp silver image and in the sense of achievement derived from the dedication and hand-crafting required to make a daguerreotype.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Stokstad, Marilyn; David Cateforis, Stephen Addiss (2005). Art History (Second ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education. pp. 964–967. ISBN 0-13-145527-3.

- ↑ http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/daghtml/dagdag.html

- ↑ Szabadváry, Ferenc (1992). History of analytical chemistry. Taylor & Francis. p. 17. ISBN 2881245692. http://books.google.com/books?id=53APqy0KDaQC.

- ↑ "The First Photograph - Heliography". http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/wfp/heliography.html. Retrieved 2009-09-29. "from Helmut Gernsheim's article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ... In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate ... The sunlight passing through ... This first permanent example ... was destroyed ... some years later."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "A Daguerreotype of Daguerre". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. http://historywired.si.edu/object.cfm?ID=458. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ Articles by R. Derek Wood on the history of the daguerreotype at "Midley History of early Photography". http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20100311230213/http://www.midley.co.uk/.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. Jules Itier. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ Henisch, Heinz K. The painted photograph. Magazine Antiques, October 1998. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ Wood, R. Derek. "The Daguerreotype in England: Some Primary Material Relating to Beard's Lawsuits." History of Photography, October 1979, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 305–9.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. Antoine Claudet. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. Thomas Richard Williams. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ Cincinnati Historical Society Library. J. P. Ball, African American Photographer. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Newhall, Beaumont. The daguerreotype in America. 3rd rev. ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1976. ISBN 0486233227.

- ↑ Leggat, Robert. A History of Photography from its Beginnings till the 1920s. Brady, Mathew. 1999. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. Thomas Martin Easterly. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. Jeremiah Gurney. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. John Plumbe, Jr. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes. Biographies. Albert S. Southworth. International Center of Photography and George Eastman House, 2005-2006. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ↑ National Portrait Gallery. A Durable Memento. Portraits by Augustus Washington, African American Daguerreotypist. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ J. Paul Getty Museum. Ezra Greenleaf Weld. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ "Unlocking the Secrets in Old Photographs, p. 126". 1991. http://books.google.com/books?id=Tdk4eVF0nbIC&pg=PA126&dq=mercury+poisoning+from+daguerreotypes. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ "LOT 2 - Le Daguerréotype Susse Frères". WestLicht Auction. May 2007. http://www.westlicht-auction.com/index.php?id=76799&acat=76799&lang=3. Retrieved 2007-08-30.. A slightly different value is given by AFP: "Oldest/Most Expensive Camera". Media Speak, Inc.. 2007-05-28. http://www.pixnoir.com/2007/05/oldestmost_expensive_camera.php. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ↑ http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/news/artmarketwatch/artmarketwatch10-27-06.asp

Further reading

- Gernsheim, Helmut, and Alison Gernsheim. L.J.M. Daguerre: the history of the diorama and the daguerreotype. New York: Dover Publications, 1968. ISBN 048622290X

- Rudisill, Richard. Mirror image: the influence of the daguerreotype on American society. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1971.

- Coe, Brian. The birth of photography: the story of the formative years, 1800-1900. London: Ash & Grant, 1976. ISBN 0904069060

- Sobieszek, Robert A, Odette M Appel-Heyne, and Charles R Moore. The spirit of fact: the daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes, 1843-1862. Boston: D.R. Godine, 1976. ISBN 0879231793

- Pfister, Harold Francis. Facing the light: historic American portrait daguerreotypes : an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, September 22, 1978-January 15, 1979. Washington, DC: Published for the National Portrait Gallery by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978.

- Richter, Stefan. The art of the daguerreotype. London: Viking, 1989. ISBN 067082688X

- Barger, M Susan, and William B White. The daguerreotype: nineteenth-century technology and modern science. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991. ISBN 0874743486

- Wood, John. America and the daguerreotype. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991. ISBN 0877453349

- Wood, John. The scenic daguerreotype: Romanticism and early photography. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1995. ISBN 0877455112

- Lowry, Bates, and Isabel Lowry. The silver canvas: daguerreotype masterpieces from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: The Museum, 1998. ISBN 0892363681

- Davis, Keith F, Jane Lee Aspinwall, and Marc F Wilson. The origins of American photography: from daguerreotype to dry-plate, 1839-1885. Kansas City, MO: Hall Family Foundation, 2007. ISBN 9780300122862

External links

- Contemporary Daguerreotypes community (non profit org)

- The Daguerreian Society: History, and predominantly US oriented database & galleries

- The Daguerreotype: an Archive of Source Texts, Graphics, and Ephemera

- Daguerreotype Portraits and Views, 1836-1864: US Library of Congress

- The American Handbook of the Daguerreotype from Project Gutenberg

- The Social Construction of the American Daguerreotype Portrait

- Article on daguerreotypes from Discover Magazine

- A University of Utah Podcast on Daguerreotype Theories

- Daguerreotype Plate Sizes

- Library of Congress Collection

- Cased Photos The Boston Public Library's Cased Photo Collection on Flickr.com

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||