Wales

| Wales

Cymru

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Motto: Cymru am byth (English: "Wales forever") |

||||

| Anthem: "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau" (English: "Land of my fathers") |

||||

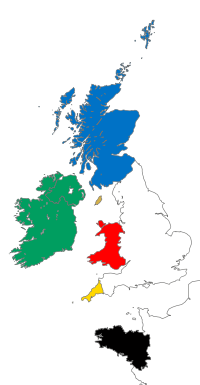

Location of Wales (orange)

– in the European continent (camel & white) |

||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Cardiff, (Caerdydd) |

|||

| National languages | Welsh, English | |||

| Demonym | Welsh, (Cymry) | |||

| Government | Devolved Government in a Constitutional monarchy | |||

| - | Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||

| - | First Minister of Wales (Head of Welsh Assembly Government) | Carwyn Jones AM | ||

| - | Deputy First Minister for Wales | Ieuan Wyn Jones AM | ||

| - | Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | David Cameron MP | ||

| - | Secretary of State (in the UK government) | Cheryl Gillan MP | ||

| Legislature | UK Parliament National Assembly for Wales |

|||

| Unification | ||||

| - | by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn[1] | 1056 | ||

| Area | ||||

| - | Total | 20,779 km2 8,022 sq mi |

||

| Population | ||||

| - | 2009 estimate | 2,999,3001 | ||

| - | 2001 census | 2,903,085 | ||

| - | Density | 140/km2 361/sq mi |

||

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 (for national statistics) estimate | |||

| - | Total | US$85.4 billion | ||

| - | Per capita | US$30,546 | ||

| Currency | Pound sterling (GBP) |

|||

| Time zone | GMT (UTC0) | |||

| - | Summer (DST) | BST (UTC+1) | ||

| Date formats | d/m/yy (AD) | |||

| Internet TLD | .uk2 | |||

| Calling code | 44 | |||

| Patron saint | Saint David, Dewi | |||

| 1 | Office for National Statistics – Population estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland - current datasets | |||

| 2 | Also .eu, as part of the European Union. ISO 3166-1 is GB, but .gb is unused. | |||

Wales (/ˈweɪlz/ Welsh: Cymru;[2] pronounced [ˈkəmrɨ] ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom,[3] bordered by England to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population estimated at three million and is officially bilingual with the indigenous Welsh language and English having equal status. The Welsh language is an important element of Welsh culture. Its decline has reversed over recent years, with fluent Welsh speakers estimated to be around 20% of the population of Wales.[4][5]

During the Iron Age and early medieval period, Wales was inhabited by the Celtic Britons. A distinct Welsh national identity emerged in the centuries after the Roman withdrawal from Britain in the 5th century, and Wales is regarded as one of the modern Celtic nations today.[6][7][8] In the 13th century, the defeat of Llewelyn by Edward I completed the Anglo-Norman conquest of Wales and brought about centuries of English occupation. Wales was subsequently incorporated into England with the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, creating the legal entity known today as England and Wales. Distinctive Welsh politics developed in the 19th century, and in 1881 the Welsh Sunday Closing Act became the first legislation applied exclusively to Wales. In 1999 the National Assembly for Wales was created, which holds responsibility for a range of devolved matters.

In 1955, Cardiff (Welsh: Caerdydd) was proclaimed as the capital of Wales. It is the country's most populous city with a population of 317,500. For a period it was the biggest coal port in the world,[9] and, for a few years before World War I, handled a greater tonnage of cargo than either London or Liverpool.[10] Two-thirds of the population of Wales live in South Wales, with another concentration in eastern North Wales. Tourists visiting Wales have been drawn to its "wild ... and picturesque" landscapes.[11][12] From the late 19th century onwards, Wales acquired its popular image as the "land of song", attributable in part to the revival of the eisteddfod tradition.[13] Actors, singers and other artists achieving international success are celebrated in Wales.[14] Cardiff is the largest media centre in the UK outside of London.[15]

Llywelyn the Great founded the Principality of Wales in 1216. Just over a hundred years after the Edwardian Conquest, in the early 15th century Owain Glyndŵr briefly restored independence to what was to become modern Wales.[16][17] Traditionally the British Royal Family have bestowed the courtesy title of "Prince of Wales" upon the male heir apparent of the reigning monarch. Wales is sometimes referred to as the "Principality of Wales", or just the "principality",[18][19] although this has no modern geographical or constitutional basis.[20]

Contents |

Etymology

Wales

The English name Wales originates from the Germanic words Walh (singular) and Walha (plural), meaning "foreigner" or "stranger" who had been "Romanised".[21] The Ænglisc-speaking Anglo-Saxons used the term Waelisc when referring to the Celtic Britons, and Wēalas when referring to their lands.

The same etymology applies to walnut (meaning "foreign (Roman) nut") as well as the wall of Cornwall and Wallonia.[22] Old Church Slavonic also borrowed the term from the Germanic, and it is the origin of the names Wallachia and its people, the Vlachs.[23][24][25]

Cymru

The modern Welsh name for themselves is Cymry, and Cymru is Welsh for "Land of the Cymry". The etymological origin of Cymry is from the Brythonic word combrogi, meaning "fellow-countrymen".[26] The use of the word Cymry as a self-designation derives from the post-Roman Era relationship of the Welsh with the Brythonic-speaking peoples of northern England and southern Scotland, the peoples of Yr Hen Ogledd (English: The Old North). In its original use, it amounted to a self-perception that the Welsh and the "Men of the North" were one people, exclusive of all others.[27] In particular, the term was not applied to the Cornish or the Breton peoples, who are of similar heritage, culture, and language to both the Welsh and the Men of the North. The word came into use as a self-description probably before the 7th century.[28] It is attested in a praise poem to Cadwallon ap Cadfan written c. 633.[29]

In Welsh literature the word Cymry was used throughout the Middle Ages to describe the Welsh, though the older, more generic term Brythoniaid continued to be used to describe any of the Britonnic peoples (including the Welsh) and was the more common literary term until c. 1100. Thereafter Cymry prevailed as a reference to the Welsh. Until circa 1560 Cymry was used indiscriminately to mean either the people (Cymry) or their homeland (Cymru).[26]

The Latinised form of the name is Cambria. Outside of Wales this form survives as the name of Cumbria in North West England, which was once a part of Yr Hen Ogledd. It is used to represent a geological period (the Cambrian) and in evolutionary studies to represent the period when most major groups of complex animals appeared (the Cambrian explosion). This form also appears at times in literary references, perhaps most notably in the pseudohistorical Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth, where the character of Camber is described as the eponymous King of Cymru.

It has occasionally been suggested, both in outdated historical sources and by some modern writers, that the Cymry were somehow linked to the 2nd century BC Cimbri or to the 7th century BC Cimmerians because of the phonetic similarity. Such suggestions have long been dismissed by scholars on etymological and other grounds.[30][31]

History

Prehistoric origins

Wales has been inhabited by modern humans for at least 29,000 years.[32] Continuous human habitation dates from the end of the last ice age, between 12,000 and 10,000 years before present (BP), when Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from central Europe began to migrate to Great Britain. Wales was free of glaciers by about 10,250 BP, the warmer climate allowing the area to become heavily wooded. People would have been able to walk between continental Europe and Great Britain until about 7,000-6,000 BP, before the post-glacial rise in sea level made Great Britain an island.[33][34] John Davies has theorised that the story of Cantre'r Gwaelod's drowning and tales in the Mabinogion, of the waters between Wales and Ireland being narrower and shallower, may be distant folk memories of this time.[33]

Neolithic colonists integrated with the indigenous people, gradually changing their lifestyles from a nomadic life of hunting and gathering, to become settled farmers – the Neolithic Revolution.[33][35] They cleared the forests to establish pasture and to cultivate the land, developed new technologies such as ceramics and textile production, and built cromlechs such as Pentre Ifan, Bryn Celli Ddu and Parc Cwm long cairn between about 5,500 BP and 6,000 BP, about 1,000 to 1,500 years before either Stonehenge or the Great Pyramid of Giza was completed.[36][37][38][39][40]

In common with people living all over Great Britain, over the following centuries the people living in what was to become known as Wales assimilated immigrants and exchanged ideas of the Bronze Age and Iron Age Celtic cultures. According to John T. Koch and others, Wales in the Late Bronze Age was part of a maritime trading-networked culture that also included the other Celtic nations, England, France, Spain and Portugal where Celtic languages developed.[41][42][43][44][45] By the time of the Roman invasion of Britain the area of modern Wales had been divided among the tribes of the Deceangli, Ordovices, Cornovii, Demetae and Silures for centuries.[46]

Colonisation

The first documented history of the area that would become Wales was in AD 48. Following attacks by the Silures of southeast Wales, in AD 47 and 48, the Roman historian Tacitus recorded that the governor of the new Roman province of Britannia "received the submission of the Deceangli" in north-east Wales.[47]

A string of Roman forts was established across what is now the South Wales region, as far west as Carmarthen (Caerfyrddin; Latin: Maridunum), and gold was mined at Dolaucothi in Carmarthenshire. There is evidence that the Romans progressed even farther west. They also built the Roman legionary fortress at Caerleon (Latin: Isca Silurum), of which the magnificent amphitheatre is the best preserved in Britain.

The Romans were also busy in northern Wales, and the mediaeval Welsh tale Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig (dream of Macsen Wledig) claims that Magnus Maximus (Macsen Wledig), one of the last western Roman Emperors, married Elen or Helen, the daughter of a Welsh chieftain from Segontium, present-day Caernarfon.[48] It was in the 4th century during the Roman occupation that Christianity was introduced to Wales.

After the Roman withdrawal from Britain in 410, much of the lowlands were overrun by various Germanic tribes.[49] However, Gwynedd, Powys, Dyfed and Seisyllg, Morgannwg, and Gwent emerged as independent Welsh successor states. They endured, in part because of favourable geographical features such as uplands, mountains, and rivers and a resilient society that did not collapse with the end of the Roman civitas.

This tenacious survival by the Romano-Britons and their descendants in the western kingdoms was to become the foundation of what we now know as Wales. With the loss of the lowlands, England's kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria, and later Wessex, wrestled with Powys, Gwent, and Gwynedd to define the frontier between the two peoples.

Having lost much of what is now the West Midlands to Mercia in the 6th and early 7th centuries, a resurgent late-seventh-century Powys checked Mercian advancement. Aethelbald of Mercia, looking to defend recently acquired lands, had built Wat's Dyke. According to John Davies, this endeavour may have been with Powys king Elisedd ap Gwylog's own agreement, however, for this boundary, extending north from the valley of the River Severn to the Dee estuary, gave Oswestry to Powys.[50] King Offa of Mercia seems to have continued this consultative initiative when he created a larger earthwork, now known as Offa's Dyke (Welsh: Clawdd Offa). Davies wrote of Cyril Fox's study of Offa's Dyke:

In the planning of it, there was a degree of consultation with the kings of Powys and Gwent. On the Long Mountain near Trelystan, the dyke veers to the east, leaving the fertile slopes in the hands of the Welsh; near Rhiwabon, it was designed to ensure that Cadell ap Brochwel retained possession of the Fortress of Penygadden." And for Gwent Offa had the dyke built "on the eastern crest of the gorge, clearly with the intention of recognizing that the River Wye and its traffic belonged to the kingdom of Gwent.[50]

However, Fox's interpretations of both the length and purpose of the Dyke have been questioned by more recent research.[51] Offa's Dyke largely remained the frontier between the Welsh and English, though the Welsh would recover by the 12th century the area between the Dee and the Conwy known then as the Perfeddwlad. By the eighth century, the eastern borders with the Anglo-Saxons had broadly been set.

Following the successful examples of Cornwall in 722 and Brittany in 865, the Britons of Wales made their peace with the Vikings and asked the Norsemen to help the Britons fight the Anglo-Saxons of Mercia to prevent an Anglo-Saxon conquest of Wales. In AD 878 the Britons of Wales unified with the Vikings of Denmark to destroy an Anglo-Saxon army of Mercians. Like Cornwall in 722, this decisive defeating of the Saxons gave Wales some decades of peace from Anglo-Saxon attack. In 1063, the Welsh prince Gruffydd ap Llywelyn made an alliance with Norwegian Vikings against Mercia which, as in AD 878 was successful, and the Saxons of Mercia defeated. As with Cornwall and Brittany, Viking aggression towards the Saxons/Franks ended any chance of the Anglo-Saxons/Franks conquering their Celtic neighbours.

Medieval Wales

The southern and eastern lands lost to English settlement became known in Welsh as Lloegyr (Modern Welsh Lloegr), which may have referred to the kingdom of Mercia originally, and which came to refer to England as a whole.[52] The Germanic tribes who now dominated these lands were invariably called Saeson, meaning "Saxons". The Anglo-Saxons called the Romano-British 'Walha', meaning 'Romanised foreigner' or 'stranger'.[23]

The Welsh continued to call themselves Brythoniaid (Brythons or Britons) well into the Middle Ages, though the first use of Cymru and y Cymry is found as early as 633 in the Gododdin of Aneirin. In Armes Prydain, written in about 930, the words Cymry and Cymro are used as often as 15 times. However, it was not until about the 12th century, that Cymry began to overtake Brythoniaid in their writings.

From 800 onwards, a series of dynastic marriages led to Rhodri Mawr's (r. 844–77) inheritance of Gwynedd and Powys. His sons in turn would found three principal dynasties (Aberffraw for Gwynedd, Dinefwr for Deheubarth, and Mathrafal for Powys), each competing for hegemony over the others.

Rhodri's grandson Hywel Dda (r. 900–50) founded Deheubarth out of his maternal and paternal inheritances of Dyfed and Seisyllwg, ousted the Aberffraw dynasty from Gwynedd and Powys, and codified Welsh law in 930, finally going on a pilgrimage to Rome (and allegedly having the Law Codes blessed by the Pope). Maredudd ab Owain (r. 986–99) of Deheubarth (Hywel's grandson) would, (again) temporarily oust the Aberffraw line from control of Gwynedd and Powys.

Maredudd's great-grandson (through his daughter Princess Angharad) Gruffydd ap Llywelyn (r. 1039–63) would conquer his cousins' realms from his base in Powys, and even extend his authority into England. Historian John Davies states that Gruffydd was "the only Welsh king ever to rule over the entire territory of Wales... Thus, from about 1057 until his death in 1063, the whole of Wales recognised the kingship of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn. For about seven brief years, Wales was one, under one ruler, a feat with neither precedent nor successor."[53] Owain Gwynedd (1100–70) of the Aberffraw line was the first Welsh ruler to use the title princeps Wallensium (prince of the Welsh), a title of substance given his victory on the Berwyn Mountains, according to John Davies.[54]

The Aberffraw dynasty would surge to pre-eminence with Owain Gwynedd's grandson Llywelyn Fawr (the Great) (b.1173–1240), wrestling concessions out of the Magna Carta in 1215 and receiving the fealty of other Welsh lords in 1216 at the council at Aberdyfi, becoming the first Prince of Wales. His grandson Llywelyn II also secured the recognition of the title Prince of Wales from Henry III with the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267. Later however, a succession of disputes, including the imprisonment of Llywelyn's wife Eleanor, daughter of Simon de Montfort, culminated in the first invasion by Edward I.

As a result of military defeat, the Treaty of Aberconwy exacted Llywelyn's fealty to England in 1277. Peace was short lived and with the 1282 Edwardian conquest the rule of the Welsh princes permanently ended. With Llywelyn's death and his brother prince Dafydd's execution, the few remaining Welsh lords did homage for their lands to Edward I. Llywelyn's head was then carried through London on a spear; his baby daughter Gwenllian was locked in the priory at Sempringham, where she remained until her death 54 years later.[55]

To help maintain his dominance, Edward constructed a series of great stone castles. Beaumaris, Caernarfon, and Conwy were built mainly to overshadow the Welsh royal home and headquarters Garth Celyn, Aber Garth Celyn, on the north coast of Gwynedd.

After the failed revolt in 1294–95 of Madog ap Llywelyn – who styled himself Prince of Wales in the so-called Penmachno Document – there was no major uprising until that led by Owain Glyndŵr a century later, against Henry IV of England. In 1404 Owain was reputedly crowned Prince of Wales in the presence of emissaries from France, Spain and Scotland; he went on to hold parliamentary assemblies at several Welsh towns, including Machynlleth. The rebellion was ultimately to founder, however, and Owain went into hiding in 1412, with peace being essentially restored in Wales by 1415.

Although the English conquest of Wales took place under the 1284 Statute of Rhuddlan, a formal Union did not occur until 1536,[18] shortly after which Welsh law, which continued to be used in Wales after the conquest, was fully replaced by English law under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542.

Industrial Wales

Prior to the British Industrial Revolution, which saw a rapid expansion between 1750 and 1850, there were signs of small-scale industries scattered throughout Wales.[56] These ranged from industries connected to agriculture, such as milling and the manufacture of woollen textiles, through to mining and quarrying.[56] Until the Industrial Revolution, Wales had always been reliant on its agricultural output for its wealth and employment and the earliest industrial businesses were small scale and localised in manner.[56]

The emerging industrial period commenced around the development of copper smelting in the Swansea area. With access to local coal deposits and a harbour that could take advantage of Cornwall's copper mines and the copper deposits being extracted from the then largest copper mine in the world at Parys Mountain on Anglesey, Swansea developed into the world's major centre for non-ferrous metal smelting in the 19th century.[56] The second metal industry to expand in Wales was iron smelting, and iron manufacturing became prevalent in both the north and the south of the country.[57] In the north of Wales, John Wilkinson's Ironworks at Bersham was a significant industry, while in the south, a second world centre of metallurgy was founded in Merthyr Tydfil, where the four ironworks of Dowlais, Cyfarthfa, Plymouth and Penydarren became the most significant hub of iron manufacture in Wales.[57] In the 1820s, south Wales alone accounted for 40% of all pig iron manufactured in Britain.[57]

In the late 18th century, slate quarrying began to expand rapidly, most notably in north Wales. The most notable site, opened in 1770 by Richard Pennant, is Penrhyn Quarry, which by the late 19th century was employing 15,000 men;[58] and along with Dinorwic Quarry, dominated the Welsh slate trade. Although slate quarrying has been described as 'the most Welsh of Welsh industries',[59] it is coal mining which has become the single industry synonymous with Wales and its people. Initially coal seams were exploited to provide energy for local metal industries, but with the opening of canal systems and later the railways, Welsh coal mining saw a boom in its demand. As the south Wales coalfield was exploited, mainly in the upland valleys around Aberdare and later the Rhondda, the ports of Swansea, Cardiff and later Penarth, grew into world exporters of coal, and with them came a population boom. By its height in 1913, Wales was producing almost 61 million tons of coal,[60] but when the heavy industries collapsed after World War II, the towns centred around these industries also went into a deep depression, with massive unemployment and emigration.

As Wales was reliant on the production of capital goods rather than of consumer goods, there were little skilled craftspeople and artisans that existed in the workshops of Birmingham and Sheffield in England. Therefore there were few factories producing finished goods in Wales, a key feature when considering regions associated with the Industrial Revolution.[57] Though there is increasing support that the revolution was reliant on harnessing the energy and materials provided by Wales, and in that development, Wales was of central importance.[57]

Modern Wales

In the 20th century, Wales saw a revival in its national status. Plaid Cymru was formed in 1925, seeking greater autonomy or independence from the rest of the UK. In 1955, the term England and Wales became common for describing the area to which English law applied, and Cardiff was proclaimed as capital city of Wales. Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (English: The Welsh Language Society) was formed in 1962, in response to fears that the language may soon die out.

Nationalism grew, particularly following the flooding of the Tryweryn valley in 1965 to create a reservoir supplying water to the English city of Liverpool. Despite 35 of the 36 Welsh Members of Parliament (MPs) voting against the bill, with the other abstaining, Parliament still passed the bill and the village of Capel Celyn was drowned, highlighting Wales's powerlessness in her own affairs in the face of the numerical superiority of English MPs in the Westminster Parliament.[61] In 1966 the Carmarthen Parliamentary seat was won by Gwynfor Evans at a by-election, Plaid Cymru's first Parliamentary seat.[62]

Both the Free Wales Army and Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru (MAC) (English: Welsh Defence Movement) were formed as a direct result of the Tryweryn destruction,[63] conducting campaigns from 1963. In the years leading up to the investiture of Prince Charles as Prince of Wales in 1969, these groups were responsible for a number of bomb blasts—destroying water pipes, tax and other offices, and part of a dam being built for a new English-backed project in Clywedog, Montgomeryshire.[63] In 1967, the Wales and Berwick Act 1746 was repealed for Wales, and a legal definition of Wales, and of the boundary with England was stated.

The Wales referendum, 1979 in which the Welsh electorate voted on the creation of an assembly for Wales resulted in a large majority for the "no" vote. However, in 1997 a referendum on the same issue secured a "yes", although by a very narrow majority. The National Assembly for Wales (Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru) was set up in 1999 (as a consequence of the Government of Wales Act 1998) and possesses the power to determine how the central government budget for Wales is spent and administered (although the UK parliament reserves the right to set limits on the powers of the Welsh Assembly).

The 1998 Act was amended by the Government of Wales Act 2006 which enhanced the Assembly's powers, giving it legislative powers akin to the Scottish Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly. Following the 2007 Assembly election, the One Wales Government was formed under a coalition agreement between Plaid Cymru and the Welsh Labour Party, under that agreement, a convention is due to be established to discuss further enhancing Wales's legislative and financial autonomy. A referendum on giving the Welsh assembly full law-making powers is promised "as soon as practicable, at or before the end of the assembly term (in 2011)" and both parties have agreed "in good faith to campaign for a successful outcome to such a referendum".[65]

Government and politics

Constitutionally, the United Kingdom is de jure a unitary state with one sovereign parliament and government in Westminster. Referenda held in Wales and Scotland in 1997 chose to establish a limited form of self-government in both countries. In Wales, the consequent process of devolution began with the Government of Wales Act 1998, which created the National Assembly for Wales (Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru).[66] Powers of the Secretary of State for Wales were transferred to the devolved government on 1 July 1999, granting the Assembly responsibility to decide how the Westminster government's budget for devolved areas is spent and administered.[67]

There are twenty areas of devolved responsibility, which include agriculture, economic development, education, health, housing, local government, social services, tourism, transport, and the Welsh language. The National Assembly originally had no primary legislative powers, but since the Government of Wales Act 2006 came into effect in 2007, it has power to pass primary legislation as Assembly Measures on some specific matters within the areas of devolved responsibility. More matters have subsequently been added either directly by the UK Parliament, or by the UK Parliament approving a request for additional legislative competence from the National Assembly. The GoWA 2006 allows for the Assembly to gain primary lawmaking powers on a more extensive range of matters within the same devolved areas if approved in a referendum, and such legislation will then take the form of Acts of the Assembly. This referendum is likely to take place in March 2011.

The Assembly consists of 60 members, known as "Assembly Members (AM)". Forty of the AMs are elected under the First Past the Post system, with the other 20 elected via the Additional Member System via regional lists in five different regions. The Assembly must elect a First Minister of Wales, who selects ministers to form the Welsh Assembly Government.

The First Minister of Wales is Carwyn Jones (since 2009), of the Labour Party, with 26 of 60 seats.[68] After the National Assembly for Wales election, 2007 Welsh Labour and Plaid Cymru; The Party of Wales, which favours Welsh independence from the rest of the United Kingdom entered into a coalition partnership to form a stable government with the "historic" One Wales agreement.

As the second-largest party in the Assembly with 14 out of 60 seats, Plaid Cymru is led by Ieuan Wyn Jones, Deputy First Minister of Wales. The Presiding Officer of the Assembly is Plaid Cymru member Lord Elis-Thomas. Other parties include the Conservative Party, currently the loyal opposition with 13 seats, and the Liberal Democrats with six seats. The "Lib Dems" had previously formed part of a coalition government with Labour in the first Assembly. There is one independent member.

In the House of Commons – the lower house of the UK government – Wales is represented by 40 MPs (of 646) from Welsh constituencies. Labour represents 29 of the 40 seats, the Liberal Democrats hold four seats, Plaid Cymru three and the Conservatives three.[69] A Secretary of State for Wales sits in the UK cabinet and is responsible for representing matters that pertain to Wales. The Wales Office is a department of the United Kingdom government, responsible for Wales. Cheryl Gillan has been Secretary of State for Wales since 12 May 2010, replacing Peter Hain of the previous Labour administration. Gillan was appointed to the new Conservative-Liberal coalition Westminster government following the United Kingdom general election of 2010.[70]

Wales is also a distinct UK electoral region of the European Union represented by four Members of the European Parliament.

Local government

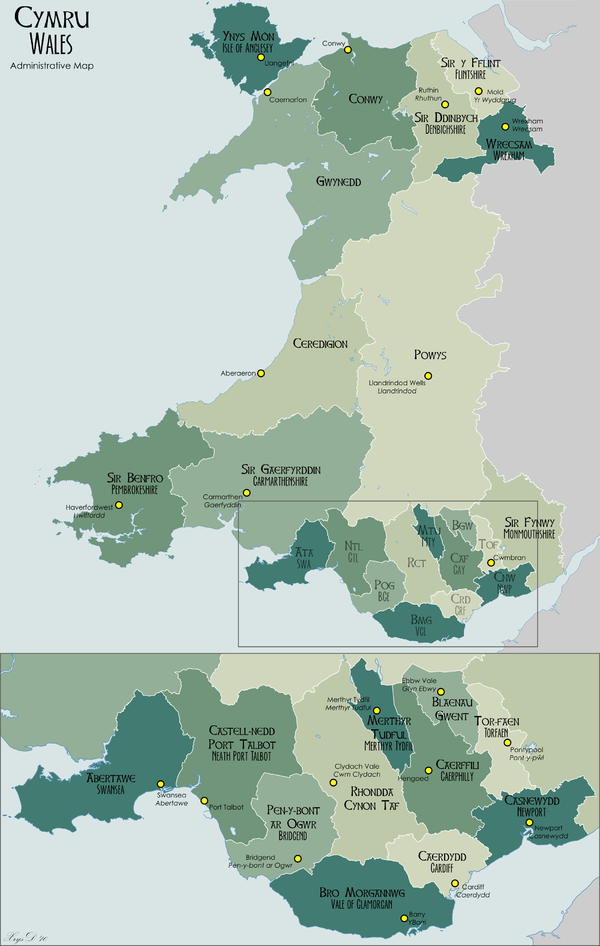

For the purposes of local government, Wales was divided into 22 council areas in 1996. These "unitary authorities" are responsible for the provision of all local government services.

Map of unitary authority areas

|

|

Areas are Counties, unless marked * (for Cities) or † (for County Boroughs). Welsh language forms are given in parentheses, where they differ from the English..

Note that there are five cities in total in Wales: in addition to Cardiff, Newport and Swansea, the communities of Bangor and St David's also have UK city status.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Law

England fully annexed Wales under the Laws in Wales Act 1535, in the reign of King Henry VIII. Prior to that Welsh Law had survived de facto after the conquest up to the 15th century in areas remote from direct English control. The Wales and Berwick Act 1746 provided that all laws that applied to England would automatically apply to Wales (and Berwick-upon-Tweed, a town located on the Anglo-Scottish border) unless the law explicitly stated otherwise. This act, with regard to Wales, was repealed in 1967. However, England and Wales persist as a single legal entity which share the same legal system—except for a few changes to accommodate the autonomy recently afforded to Wales. In this sense, English law is the law of Wales.

English law is regarded as a common law system, with no major codification of the law, and legal precedents are binding as opposed to persuasive. The court system is headed by the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom which is the highest court of appeal in the land for criminal and civil cases.The Supreme Court of Judicature of England and Wales is the highest court of first instance as well as an appellate court. The three divisions are the Court of Appeal; the High Court of Justice and the Crown Court. Minor cases are heard by the Magistrates' Courts or the County Court.

Since devolution in 2006, the Welsh Assembly has had the authority to draft and approve some laws outside of the UK Parliamentary system to meet the specific needs of Wales. Under powers conferred by Legislative Competency Orders agreed by all parliamentary stakeholders, it is able to pass laws known as Assembly Measures in relation to specific fields, such as health and education. As such, Assembly Measures are a subordinate form of primary legislation, lacking the scope of UK-wide acts of parliament, but able to be passed without the approval of the UK parliament or Royal Assent for each 'act'. Through this primary legislation, the Welsh Assembly Government can then also draft more specific secondary legislation. With devolution, the ancient and historic Wales and Chester court circuit was also disbanded and a separate Welsh court circuit was created to allow for any Measures passed by the Assembly.

Geography and natural history

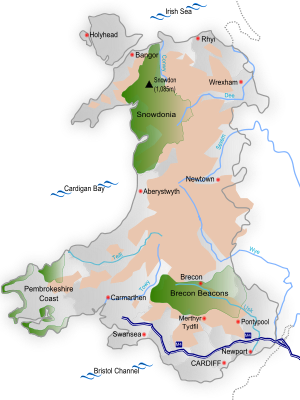

Wales is located on a peninsula in central-west Great Britain. Its area is about 20,779 km2 (8,023 sq mi) – about the same size as Massachusetts, Israel, Slovenia or El Salvador and about a quarter of the area of Scotland. It is about 274 km (170 mi) north–south and 97 km (60 mi) east–west. Wales is bordered by England to the east and by sea in the other three directions: the Môr Hafren (Bristol Channel) to the south, Celtic Sea to the west, and the Irish Sea to the north. Altogether, Wales has over 1,200 km (746 mi) of coastline. There are several islands off the Welsh mainland, the largest being Ynys Môn (Anglesey) in the northwest.

Much of Wales's diverse landscape is mountainous, particularly in the north and central regions. The mountains were shaped during the last ice age, the Devensian glaciation. The highest mountains in Wales are in Snowdonia (Eryri), and include Snowdon (Yr Wyddfa), which, at 1,085 m (3,560 ft) is the highest peak in Wales. The 14 (or possibly 15) Welsh mountains over 3,000 feet (914 m) high are known collectively as the Welsh 3000s, and are located in a small area in the north-west.

The highest outside the 3000s is Aran Fawddwy 905m (2,969 ft) in the south of Snowdonia. The Brecon Beacons (Bannau Brycheiniog) are in the south (highest point Pen-y-Fan 886 m/2,907 ft, and are joined by the Cambrian Mountains in Mid Wales (after which the earliest geological period of the Paleozoic era, the Cambrian, is named).

In the mid-19th century, two prominent geologists, Roderick Murchison and Adam Sedgwick, used their studies of the geology of Wales to establish certain principles of stratigraphy and palaeontology. After much dispute, the next two periods of the Paleozoic era, the Ordovician and Silurian, were named after ancient Celtic tribes from this area. The older rocks underlying the Cambrian rocks were referred to as Pre-cambrian.

Wales has three national parks: Snowdonia, Brecon Beacons and Pembrokeshire Coast. It has four Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. These areas include Anglesey, the Clwydian Range, the Gower Peninsula and the Wye Valley. The Gower Peninsula was the first area in the whole of the United Kingdom to be designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, in 1956.

Much of the coastline of South and West Wales is designated as Heritage Coast. The coastline of the Glamorgan Heritage Coast, the Gower Peninsula, Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire, and Ceredigion is particularly wild and impressive. Gower, Carmarthenshire, Pembrokeshire and Cardigan Bay all have clean blue water, white sand beaches and impressive marine life. Despite this scenic splendour the coast of Wales has a dark side; the south and west coasts of Wales, along with the Irish and Cornish coasts, are frequently blasted by huge Atlantic westerlies/south westerlies that, over the years, have sunk and wrecked many vessels.

On the night of 25 October 1859, 114 ships were destroyed off the coast of Wales when a hurricane blew in from the Atlantic; Cornwall and Ireland also had a huge number of fatalities on its coastline from shipwrecks that night. Wales has the somewhat unenviable reputation, along with Cornwall, Ireland and Brittany, of having per square mile, some of the highest shipwreck rates in Europe. The shipwreck situation was particularly bad during the industrial era when ships bound for Cardiff got caught up in Atlantic gales and were decimated by "the cruel sea".

The modern border between Wales and England was largely defined in the 16th century, based on medieval feudal boundaries. The boundary line (which very roughly follows Offa's Dyke up to 40 mi (64 km) of the northern coast) separates Knighton from its railway station, virtually cuts off Church Stoke from the rest of Wales, and slices straight through the village of Llanymynech (where a pub actually straddles the line).

The Seven Wonders of Wales is a list in doggerel verse of seven geographic and cultural landmarks in Wales probably composed in the late 18th century under the influence of tourism from England.[72] All the "wonders" are in north Wales: Snowdon (the highest mountain), the Gresford bells (the peal of bells in the medieval church of All Saints at Gresford), the Llangollen bridge (built in 1347 over the River Dee, Afon Dyfrdwy), St Winefride's Well (a pilgrimage site at Holywell) in Flintshire, the Wrexham (Wrecsam) steeple (16th century tower of St. Giles Church in Wrexham), the Overton Yew trees (ancient yew trees in the churchyard of St. Mary's at Overton-on-Dee) and Pistyll Rhaeadr – a tall waterfall, at 240 ft (73 m). The wonders are part of the rhyme:

- Pistyll Rhaeadr and Wrexham steeple,

- Snowdon's mountain without its people,

- Overton yew trees, St Winefride's Wells,

- Llangollen bridge and Gresford bells.

Climate

- Highest maximum temperature: 35.2 °C (95.4 °F) at Hawarden Bridge, Flintshire on 2 August 1990.

- Lowest minimum temperature: −23.3 °C (−9.9 °F) at Rhayader, Radnorshire (now Powys) on 21 January 1940.[73]

- Maximum number of hours of sunshine in a month: 354.3 hours at Dale Fort, Pembrokeshire in July 1955.[74]

- Minimum number of hours of sunshine in a month: 2.7 hours at Llwynon, Brecknockshire in January 1962.[75]

- Maximum rainfall in a day (0900 UTC – 0900 UTC): 211 millimetres (8 in) at Rhondda, Glamorgan, on 11 November 1929.[76]

- Wettest spot – an average of 4,473 millimetres (176 in) rain a year at Crib Goch in Snowdonia, Gwynedd (making it also the wettest spot in the United Kingdom).[77][78]

Flora and fauna

Wales’ wildlife is typical of Britain with several distinctions. Due to its long coastline, and being a peninsular country, Wales hosts a variety of seabirds. The coasts and surrounding islands are home to colonies of gannets, Manx Shearwater, puffins, kittiwakes, shags and razorbills. In comparison, with 60% of Wales above the 150m contour, the country also supports a variety of upland habitat birds, including raven and ring ouzel.[79][80] Birds of prey include the merlin, hen harrier and the red kite, a national symbol of Welsh wildlife.[81] In total more than 200 different species of bird have been seen at the RSPB reserve at Conwy, including seasonal visitors.[82]

The larger Welsh mammals died out during the Norman period, including the brown bear, wolf and the wildcat.[83] Today mammals of note include shrews, voles, badgers, hedgehogs and fifteen species of bat.[83] Two rare species of small rodent, the yellow-necked mouse and the dormouse, are of special Welsh note being found at the historically undisturbed border area.[83] Other animals of note include, otter, stoat and weasel.

Like Cornwall, Brittany and Ireland, the waters of South-west Wales of Gower, Pembrokeshire and Cardigan Bay attract marine animals including basking sharks, Atlantic grey seals, leatherback turtles, dolphins, porpoises, jellyfish, crabs and lobsters. Pembrokeshire and Ceredigion in particular are recognised as an area of international importance for Bottlenose dolphins, and New Quay has the only summer residence of bottlenose dolphins in the whole of the UK. River fish of note include char, eel, salmon, shad, sparling and Arctic char, whilst the Gwyniad is unique to Wales, found only in Bala Lake.[84] Wales is also known for its shellfish, including cockles, limpet, mussels and periwinkles.[85] Herring, mackerel and hake are the more common of the country's seafish.[86]

The north facing high grounds of Snowdonia support a relic pre-glacial flora including the iconic Snowdon lily -Lloydia serotina -and other alpine species such as Saxifraga cespitosa, Saxifraga oppositifolia and Silene acaulis - an eco-system not found elsewhere in the UK. Wales also hosts a number of plant species not found elsewhere in the UK including the Spotted Rock-rose Tuberaria guttata on Anglesey and Draba aizoides [87] on the Gower.

Economy

Parts of Wales have been heavily industrialised since the 18th century and the early Industrial Revolution. Coal, copper, iron, silver, lead, and gold have been extensively mined in Wales, and slate has been quarried. By the second half of the 19th century, mining and metallurgy had come to dominate the Welsh economy, transforming the landscape and society in the industrial districts of south and north-east Wales.

From the middle of the 19th century until the mid-1980s, the mining and export of coal was a major part of the Welsh economy. Cardiff was once the largest coal exporting port in the world[9] and, for a few years before World War One, handled a greater tonnage of cargo than either London or Liverpool.[10]

From the early 1970s, the Welsh economy faced massive restructuring with large numbers of jobs in traditional heavy industry disappearing and being replaced eventually by new ones in light industry and in services. Over this period Wales was successful in attracting an above average share of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the UK. However, much of the new industry has essentially been of a "branch factory" type, often routine assembly employing low skilled workers. The Cardiff-based Bank of Wales was established in 1971,[88] but was later taken over by HBOS and absorbed into the parent company.

Wales has struggled to develop or attract high value-added employment in sectors such as finance and research and development,[89] attributable in part to a comparative lack of 'economic mass' (i.e. population) – Wales lacks a large metropolitan centre.[90] The lack of high value-added employment is reflected in lower economic output per head relative to other regions of the UK – in 2002 it stood at 90 per cent of the EU25 average and around 80 per cent of the UK average. However, care is needed in interpreting these data, which do not take account of regional differences in the cost of living. When this is taken into account, the gap in real living standards between Wales and more prosperous parts of the UK is not pronounced.[91] In June 2008, Wales made history by becoming the first nation in the world to be awarded Fairtrade Status.[92]

In 2002, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Wales was just over £26 billion ($48 billion), giving a per capita GDP of £12,651 ($19,546). As of 2006, the unemployment rate in Wales stood at 5.7% – above the UK average, but lower than in the majority of EU countries.

As with the rest of the United Kingdom, the currency used in Wales is the pound sterling, represented by the symbol £. The Bank of England, created as the central bank for the Kingdom of England (which included Wales), is responsible for the currency of the entire UK. Unlike in Scotland and Northern Ireland, there are no Welsh banks with the right to issue their own banknotes. The Royal Mint, who issue the coinage circulated over the whole of the UK, have been based at a single site in Llantrisant, south Wales since 1980, having been progressively transferring operations from their Tower Hill, London site since 1968.[93] Since decimalisation, in 1971, at least one of the coins in UK circulation has depicted a Welsh design, e.g. the 1995 and 2000 one Pound coin (shown left). However, Wales has not been represented on any coin minted from 2008.[94]

Due to poor-quality soil, much of Wales is unsuitable for crop-growing, and livestock farming has traditionally been the focus of agriculture. The Welsh landscape (protected by three national parks) and 45 Blue Flag beaches, as well as the unique culture of Wales, attract large numbers of tourists, who play an especially vital role in the economy of rural areas.[95][96]

Healthcare

Public healthcare in Wales is provided by NHS Wales (Welsh: GIG Cymru), which was originally formed as part of the NHS structure for England and Wales created by the National Health Service Act 1946, but with powers over the NHS in Wales coming under the Secretary of State for Wales in 1969.[97] In turn, responsibility for NHS Wales was passed to the Welsh Assembly and Executive under devolution in 1999.

NHS Wales provides public healthcare in Wales and employs some 90,000 staff, making it Wales’ biggest employer.[98] The Minister for Health and Social Services is the person within the Welsh Assembly Government who holds cabinet responsibilities for both health and social care in Wales.

Demographics

The population of Wales in the United Kingdom Census 2001 was 2,903,085, which has risen to 2,958,876 according to 2005 estimates. The main population and industrial areas are in South Wales, consisting of the cities of Cardiff (Caerdydd), Swansea and Newport and surrounding areas, with another significant population in the north-east around Wrexham.

According to the 2001 census, 96% of the population was White British, and 2.1% non-white (mainly of British Asian origin).[99] Most non-white groups were concentrated in the southern port cities of Cardiff, Newport and Swansea. Welsh Asian communities developed mainly through immigration since World War II. More recently, parts of Wales have seen an increased number of immigrants settle from recent EU accession countries such as Poland – although some Poles also settled in Wales in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

In the 2001 Labour Force Survey, 72% of adults in Wales considered their national identity as wholly and another 7% considered themselves to be partly Welsh (Welsh and British were the most common combination). A recent study estimated that 35% of the Welsh population have surnames of Welsh origin (5.4% of the English population and 1.6% of the Scottish also bore 'Welsh' names).[100] However, some names identified as English (such as 'Greenaway') may be corruptions of Welsh ('Goronwy'). Other names common in Wales, such as 'Richards', may have originated simultaneously in other parts of Britain.

In 2002, the BBC used the headline "English and Welsh are races apart" to report a genetic survey of test subjects from market towns in England and Wales.[101] Other recent researchers, such as Bryan Sykes and Stephen Oppenheimer, have argued that the majority of modern-day English and Welsh people trace a common ancestry to migrants who arrived in the British Isles during the Mesolithic and the Neolithic periods, although the National Museum Wales consider the conclusions made to date from genetic studies "implausible".[8]

In 2001 a quarter of the Welsh population were born outside Wales, mainly in England; about 3% were born outside the UK. The proportion of people who were born in Wales differs across the country, with the highest percentages in the South Wales Valleys, and the lowest in Mid Wales and parts of the north-east. In both Blaenau Gwent and Merthyr Tydfil 92% were Welsh-born, compared to only 51% in Flintshire and 56% in Powys.[102] One of the reasons for this is that the locations of the most convenient hospitals in which to give birth are over the border in England. Around 1.75 million Americans report themselves to have Welsh ancestry,[103] as did 467,000 Canadians in Canada's 2006 census.[104]

Languages

The Welsh Language Act 1993 and the Government of Wales Act 1998 provide that the English and Welsh languages be treated on a basis of equality. However, even English has only de facto status as an official language of the United Kingdom and this has led political groups like Plaid Cymru to question whether such legislation is sufficient to ensure the survival of the Welsh language.[105]

English is spoken by almost all people in Wales and is the de facto main language; Welsh English refers to the dialects of English spoken in Wales which are significantly influenced by Welsh grammar and can include words derived from Welsh. However, northern and western Wales retain many areas where Welsh is spoken as a first language by the majority of the population and English is learnt as a second language. 21.7% of the Welsh population is able to speak or read Welsh to some degree (based on the 2001 census), although only 16% claim to be able to speak, read and write it,[18] which may be related to the stark differences between colloquial and literary Welsh. According to a language survey conducted in 2004, a larger proportion than 21.7% claim to have some knowledge of the language.[106]

Today there are very few monoglot Welsh speakers, but individuals still exist who may be considered less than fluent in English and rarely speak it. Road signs in Wales are generally in both English and Welsh; where place names differ in the two languages, both versions are used (e.g. "Cardiff" and "Caerdydd"), the decision as to which is placed first being that of the local authority.

During the 20th century a number of small communities of speakers of languages other than English or Welsh, such as Bengali or Cantonese, have established themselves in Wales as a result of immigration. This phenomenon is almost exclusive to urban Wales. Code-switching is common in all parts of Wales, and the result is known by various names, such as "Wenglish" or (in Caernarfon) "Cofi".

Religion

The largest religion in Wales is Christianity, with 72% of the population describing themselves as Christian in the 2001 census. The Church in Wales with 56,000 adherents is the largest denomination.[107] It is a province of the Anglican Communion, and was part of the Church of England until disestablishment in 1920 under the Welsh Church Act 1914.

The Presbyterian Church of Wales was born out of the Welsh Methodist revival in the 18th century and seceded from the Church of England in 1811.

The Roman Catholic Church makes up the next largest denomination at 3% of the population. Non-Christian religions are small in Wales, making up approximately 1.5% of the population. 18% of people declare no religion. The Apostolic Church holds its annual Apostolic Conference in Swansea each year, usually in August. The patron saint of Wales is Saint David (Welsh: Dewi Sant), with St David's Day (Welsh: Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Sant) celebrated annually on 1 March.

In 1904, there was a religious revival (known by some as the 1904-1905 Welsh Revival or simply The 1904 Revival) which started through the evangelism of Evan Roberts and took many parts of Wales by storm with massive numbers of people voluntarily converting to nonconformist and Anglican Christianity, sometimes whole communities. Many of the present-day Pentecostal churches in Wales claim to have originated in this revival.

Islam is the largest non-Christian religion in Wales, with more than 30,000 reported Muslims in the 2001 census. There are also communities of Hindus and Sikhs mainly in the South Wales cities of Newport, Cardiff and Swansea, while curiously the largest concentration of Buddhists is in the western rural county of Ceredigion. Judaism was the first non-Christian faith (excluding pre-Roman animism) to be established in Wales, however as of the year 2001 the community has declined to approximately 2,000.[108] Paganism and Wicca are also growing in Wales. According to the 2001 Census, there are 7,000-recorded Wiccans in England and Wales, with 31,000 Pagans.[109]

Culture

| Part of a series on the | |

|---|---|

| Culture of Wales | |

|

|

| Festivals | |

| Calennig · Dydd Santes Dwynwen · Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau · Saint David's Day · Calan Mai · Calan Awst · Calan Gaeaf · Gŵyl Mabsant · Eisteddfod | |

| Dress | |

| Traditional Welsh costume | |

| Cuisine | |

| Bara brith · Bara Lafwr · Cawl · Cawl Cennin · Crempog · Gower cuisine · Selsig Morgannwg · Tatws Pum Munud · Welsh breakfast · Welsh cake · Welsh rarebit | |

| Land division | |

| Cymwd · Cantref · Historic counties | |

| Language | |

| Welsh (Cymraeg) · Welsh English · History of the Welsh language · Welsh placenames · Welsh surnames · Welsh medium education · Y Fro Gymraeg | |

| Law | |

| Welsh law · Contemporary Welsh law | |

| Literature | |

| Welsh-language literature · English-language literature · Medieval Welsh literature · Welsh-language authors · Welsh-language poets | |

| Music | |

| Cerdd Dant · Crwth · Cymanfa Ganu · Cynghanedd · Noson Lawen · Pibgorn · Tabwrdd · Telyn Deires · Twmpath · Welsh bagpipes | |

| Mythology | |

| Welsh mythology · Matter of Britain · Arthurian legend | |

| Sport | |

| Boxing · Cnapan · Cricket · Football · Rugby league · Rugby union | |

| Symbols | |

| Flag of Wales · Flag of Saint David · List of Welsh flags · Welsh Dragon · Welsh heraldry · Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau | |

|

Wales Portal |

Wales has a distinctive culture including its own language, customs, holidays and music.

Wales is primarily represented by the symbol of the red Welsh Dragon, but other national emblems include the leek and daffodil. The Welsh words for leeks (cennin) and daffodils (cennin Pedr, lit. "(Saint) Peter's Leeks") are closely related and it is likely that one of the symbols came to be used due to a misunderstanding for the other one, though it is unclear which came first.

Wales has 3 UNESCO World Heritage Sites: The Castles and Town walls of King Edward I in Gwynedd, Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Blaenavon Industrial Landscape.

Art

Many works of Celtic art have been found in Wales.[110] In the Early Medieval period, the Celtic Christianity of Wales participated in the Insular art of the British Isles and a number of illuminated manuscripts from Wales survive, of which the 8th century Hereford Gospels and Lichfield Gospels are the most notable. The 11th century Ricemarch Psalter (now in Dublin) is certainly Welsh, made in St David's, and shows a late Insular style with unusual Viking influence.

The best of the few Welsh artists of the 16th–18th centuries tended to move elsewhere to work, but in the 18th century the dominance of landscape art in English art bought them motives to stay at home, and bought an influx of artists from outside to paint Welsh scenery. The Welsh painter Richard Wilson (1714–82) is arguably the first major British landscapist, but rather more notable for Italian scenes than Welsh ones, although he did paint several on visits from London.[111]

.jpeg)

It remained difficult for artists relying on the Welsh market to support themselves until well into the 20th century. An Act of Parliament in 1857 provided for the establishment of a number of art schools throughout the United Kingdom, and the Cardiff School of Art opened in 1865. Graduates still very often had to leave Wales to work, but Betws-y-Coed became a popular centre for artists, and its artist's colony helped form the Royal Cambrian Academy in 1881.[112] The sculptor Sir William Goscombe John made many works for Welsh commissions, although he had settled in London. Christopher Williams, whose subjects were mostly resolutely Welsh, was also based in London. Thomas E. Stephens and Andrew Vicari had very successful careers as portraitists based respectively in the United States and France. Sir Frank Brangwyn was Welsh by origin, but spent little time in Wales.

Perhaps the most famous Welsh painters, Augustus John and his sister Gwen John, mostly lived in London and Paris; however the landscapists Sir Kyffin Williams and Peter Prendergast remained living in Wales for most of their lives, though well in touch with the wider art world. Ceri Richards was very engaged in the Welsh art scene as a teacher in Cardiff, and even after moving to London; he was a figurative painter in international styles including Surrealism. Various artists have moved to Wales, including Eric Gill, the London-born Welshman David Jones, and the sculptor Jonah Jones. The Kardomah Gang was a intellectual circle centred on the poet Dylan Thomas and poet and artist Vernon Watkins in Swansea, which also included the painter Alfred Janes. Today much art is produced in Wales, as elsewhere in a great diversity of styles.

South Wales had several notable potteries in the late 18th and 19th centuries, beginning with the Cambrian Pottery (1764–1870, also known as "Swansea pottery") and including Nantgarw Pottery near Cardiff, which was in operation from 1813 to 1822 making fine porcelain, and then utilitarian pottery until 1920. Portmeirion Pottery (from 1961) has never in fact been made in Wales.

Sport

The most popular sports in Wales are rugby union and football. Wales, like other constituent nations, enjoys independent representation in major world sporting events such as the FIFA World Cup, Rugby World Cup and in the Commonwealth Games (however as Great Britain in the Olympics). As in New Zealand, rugby is a core part of the national identity, although football has traditionally been the more popular sport in the North Wales.

The Welsh national rugby union team takes part in the annual Six Nations Championship and has also competed in every Rugby World Cup, hosting the tournament in 1999. Welsh teams also play in the European Heineken Cup and Magners League alongside teams from Ireland and Scotland, the EDF Energy Cup and the European Heineken Cup. The traditional club sides, were replaced in major competitions with five regional sides in 2003 replaced by the four professional regions (Scarlets, Cardiff Blues, Newport Gwent Dragons and Ospreys) in 2004.

Wales has had its own football league since 1992 although, for historical reasons, two Welsh clubs (Cardiff City, and Swansea City) play in the English Football League and another four Welsh clubs in its feeder leagues. (Wrexham, Newport County, Merthyr Tydfil, and Colwyn Bay).

In international cricket, England and Wales field a single representative team which is administered by the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB). There is a separate Wales team that occasionally participates in limited-overs domestic competition. Glamorgan County Cricket Club is the only Welsh participant in the England and Wales County Championship.

Wales has produced several world-class snooker players such as Ray Reardon, Terry Griffiths, Mark Williams, Matthew Stevens and Ryan Day. Amateur participation in the sport is very high.

Wales has also produced a number of athletes who have made a mark on the world stage, including the 110-metre hurdler Colin Jackson who is a former world record holder and the winner of numerous Olympic, World and European medals as well as Tanni Grey-Thompson who has won Paralympic gold medals and marathon victories.

Wales has produced several world-class boxers. Joe Calzaghe was WBO World Super-Middleweight Champion who then won the WBA, WBC and Ring Magazine super middleweight and Ring Magazine Light-Heavy Weight titles. Former World champions include Enzo Maccarinelli, Freddie Welsh, Colin Jones, Howard Winstone, Percy Jones, Jimmy Wilde, Steve Robinson and Robbie Regan.

Media

Cardiff is home to the Welsh national media. BBC Wales is based in Llandaff, Cardiff and produces Welsh-oriented output for BBC One and BBC Two channels. ITV the UK's main commercial broadcaster has a Welsh-oriented service branded as ITV Wales, whose studios are in Culverhouse Cross, Cardiff. S4C, based in Llanishen, Cardiff, broadcasts mostly Welsh-language programming at peak hours, but shares English-language content with Channel 4 at other times. S4C Digidol (S4C Digital) broadcasts mostly in Welsh.

BBC Radio Wales is Wales' only national English-language radio station, while BBC Radio Cymru broadcasts throughout Wales in Welsh. There are also a number of independent radio stations across Wales.

Most of the newspapers sold and read in Wales are national newspapers available throughout Britain, unlike in Scotland where many newspapers have rebranded into Scottish based titles. Wales-based newspapers include: South Wales Echo, South Wales Argus, South Wales Evening Post, Liverpool Daily Post (Welsh edition) and Y Cymro, a Welsh language publication. The Western Mail is the main indigenous daily newspaper in South Wales.

In addition to English-language magazines, a number of weekly and monthly Welsh-language magazines are published. Wales has some 20 publishing companies, publishing mostly English titles. However, some 500–600 titles are published each year in Welsh.

Cuisine

About 80% of the land surface of Wales is given over to agricultural use. However, very little of this is arable land; the vast majority consists of permanent grass pasture or rough grazing for herd animals such as sheep and cows. Although both beef and dairy cattle are raised widely, especially in Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire, Wales is more well-known for its sheep farming, and thus lamb is the meat traditionally associated with Welsh cooking.

Some traditional dishes include laverbread (made from seaweed), bara brith (fruit bread), Cawl (a lamb stew) and cawl cennin (leek soup), Welsh cakes, and Welsh lamb. Cockles are sometimes served with breakfast bacon.

Music

Wales is often referred to as "the land of song",[113] and is notable for its harpists, male choirs, and solo artists including Sir Geraint Evans, Dame Gwyneth Jones, Dame Anne Evans, Dame Margaret Price, Ivor Novello, John Cale, Sir Tom Jones, Bonnie Tyler, Bryn Terfel, Mary Hopkin, Katherine Jenkins, Meic Stevens Dame Shirley Bassey and Duffy.

The principal Welsh festival of music and poetry is the annual National Eisteddfod. The Llangollen International Eisteddfod echoes the National Eisteddfod but provides an opportunity for the singers and musicians of the world to perform.

Popular bands to have emerged from Wales have included the Beatles-nurtured power pop group Badfinger in the 1960s, Man and Budgie in the 1970s and The Alarm in the 1980s. Wales experienced a strong emergence of groups during the 1990s led by Manic Street Preachers, followed by the likes of the Stereophonics and Feeder; notable during this period were Catatonia, Super Furry Animals, and Gorky's Zygotic Mynci who gained popular success as dual-language artists.

The Welsh traditional and folk music scene is in resurgence with performers and bands such as Crasdant, Carreg Lafar, Fernhill, Siân James and The Hennessys. Traditional music and dance in Wales is supported by a myriad of societies. The Welsh Folk Song Society has published a number of collections of songs and tunes. The Welsh Folk Dance Society supports a network of national amateur dance teams and publishes support material.

Traditional instruments of Wales include telyn deires (triple harp), fiddle, crwth, pibgorn (hornpipe) and other instruments.[114][115][116][117] The Cerdd Dant Society promotes its specific singing art primarily through an annual one-day festival.

The BBC National Orchestra of Wales performs in Wales and internationally. The world-renowned Welsh National Opera now has a permanent home at the Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff Bay, while the National Youth Orchestra of Wales was the first of its type in the world.

Literature

Transport

The main road artery linking cities and other settlements along the South Wales coast is the M4 motorway which also provides a link with England and eventually London. The Welsh section of the motorway, managed by the Welsh Assembly Government, runs from the Second Severn Crossing to Pont Abraham, Carmarthenshire, connecting the cities of Cardiff, Newport and Swansea.

In North Wales the A55 expressway performs a similar role along the north Wales coast providing connections for places such as Holyhead and Bangor with Wrexham and Flintshire and also with England, principally Chester. The main north-south Wales link is the A470 which runs from Cardiff to Llandudno.

Cardiff International Airport is the only large and international airport in Wales, offering links domestically and to European and North American destinations, located some 12 miles (19 km) south-west of Cardiff city centre, in the Vale of Glamorgan. Highland Airways ran internal flights between Anglesey (Valley) and Cardiff, from May 2007 until March 2010, when the company went into administration.[118] The service, dubbed "Ieaun Air" after Deputy First Minister for Wales Ieuan Wyn Jones, AM for Ynys Môn (Anglesey), resumed on 10 May 2010 with Isle of Man airline Manx2 the carrier [119]

The country also has a significant railway network managed by the Welsh Assembly Government which has a programme of reopening old railway lines and extending rail usage. Cardiff Central and Cardiff Queen Street are the busiest and the major hubs on the internal and national network. Beeching cuts in the 1960s mean that most of the remaining network is geared toward east-west travel to or from England. Services between North and South Wales operate through the English towns of Chester and Shrewsbury. Valley Lines services operate in Cardiff, the South Wales Valleys and surrounding area and are heavily used as commuter lines.

Arriva Trains Wales is the major operator of rail services within Wales. It also operates routes from within Wales to Crewe, Manchester, Birmingham and Cheltenham. Virgin Trains operate services from North Wales to London as part of the West Coast Main Line. First Great Western operate services from London to Cardiff and Newport every half hour with an hourly continuation to Swansea. It also runs services from Cardiff and Newport to southern England. CrossCountry offer services from Cardiff to Nottingham and Newcastle upon Tyne via the West Midlands, East Midlands and Yorkshire.

Regular ferry services to Ireland operate from Holyhead and Fishguard, and the Swansea to Cork, cancelled in 2006, was reinstated in March 2010.[120]

National symbols

The Flag of Wales incorporates the red dragon (Y Ddraig Goch) of Prince Cadwalader along with the Tudor colours of green and white. It was used by Henry VII at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 after which it was carried in state to St. Paul's Cathedral. The red dragon was then included in the Tudor royal arms to signify their Welsh descent. It was officially recognised as the Welsh national flag in 1959. The British Union Flag incorporates the flags of Scotland, Ireland and England but does not have any Welsh representation. Technically it is represented by the flag of England, as the Laws in Wales act of 1535 annexed Wales following the 13th-century conquest.

The daffodil and the leek are also symbols of Wales. The origins of the leek can be traced to the 16th century, while the daffodil became popular in the 19th century, encouraged by David Lloyd-George. This is attributed to confusion of the Welsh for leek (cenhinen) and that for daffodil (cenhinen Bedr or St. Peter's leek). A report in 1916 gave preference to the leek, which has appeared on British pound coins.[121]

"Hen Wlad fy Nhadau" ("Land of My Fathers") is the National Anthem of Wales, and is played at events such as football or rugby matches involving the Wales national team as well as the opening of the Welsh Assembly and other official occasions.

Saint David's Day, 1 March, is the national day,

Welsh people

See also

- England and Wales

- National Eisteddfod of Wales

- Seven Wonders of Wales

- Wales–England border

- Welsh language

- Culture of Wales

- Welsh nationalism

- Welsh Argentine

References

- ↑ Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. p. 100. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ Also spelled "Gymru", "Nghymru" or "Chymru" in certain contexts, as Welsh is a language with initial mutations – see Welsh morphology.

- ↑ The Countries of the UK statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ "Welsh Language Board - Number of speakers". Byig-wlb.org.uk. http://www.byig-wlb.org.uk/English/welshlanguage/Pages/WhoaretheWelshspeakersWheredotheylive.aspx. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "Go Britannia! Guide to Wales - Welsh Language Guide". Britannia. http://www.britannia.com/celtic/wales/language.html. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ Davies, John, A History of Wales, Penguin, 1994, "Welsh Origins", p. 54, ISBN 0-14-014581-8

- ↑ "Welsh Assembly Government: Minister promotes Wales’ status as a Celtic nation". Welsh Assembly Government website. Welsh Assembly Government. 16 September 2002. http://new.wales.gov.uk/news/archivepress/enterprisepress/einpress2002/749669/?lang=en. Retrieved 3 Janaury 2010.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Who were the Celts? ... Rhagor". Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales website. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. 4 May 2007. http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/rhagor/article/1939/. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Coal Exchange to 'stock exchange'". BBC News Wales. 26 April 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/6586105.stm. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Rhagor, Cardiff - Coal and Shipping Metropolis of the World". Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales. Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales. 18 April 2007. http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/rhagor/article/?article_id=50. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ↑ The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales, Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2008. p.448.

- ↑ "Fast facts: Home: Visit Wales - the Welsh Assembly Government's tourism team". Industry.visitwales.co.uk. 30 June 2005. http://www.industry.visitwales.co.uk/server.php?show=nav.00700b00700e. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2008

- ↑ Why the Welsh voice is so musical, BBC News, 8 June 2006. Accessed 17 May 2008.

- ↑ Tongue tied, BBC News. Accessed 17 May 2008

- ↑ Gwynfor, Evans (1974). Land of my Fathers. Y Lolfa Cyf., Talybont. pp. 240 & 241. ISBN 0 86243 265 0.

- ↑ Gwynfor, Evans (2000). The Fight for Welsh Freedom. Y Lolfa Cyf., Talybont. p. 87. ISBN 0 86243 515 32.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Illustrated Encyclopedia of Britain. London: Reader's Digest. 1999. p. 459. ISBN 0-276-42412-3. "A country and principality within the mainland of Britain ... about half a million"

- ↑ The Oxford Illustrated Dictionary. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. 1976 [1975]. p. 949. "Wales (-lz). Principality occupying extreme W. of central southern portion of Gt Britain"

- ↑ "UN report causes stir with Wales dubbed 'Principality'". WalesOnline website. Media Wales Ltd. 3 July 2010. http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/welsh-politics/welsh-politics-news/2010/07/03/un-report-causes-stir-with-wales-dubbed-principality-91466-26777027/. Retrieved 25 July 2010. "... the Assembly’s Counsel General, John Griffiths, [said]: “I agree that, in relation to Wales, Principality is a misnomer and that Wales should properly be referred to as a country."

- ↑ Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. p. 69. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ (French) Albert Henry, Histoire des mots Wallons et Wallonie, Institut Jules Destrée, Coll. «Notre histoire», Mont-sur-Marchienne, 1990, 3rd ed. (1st ed. 1965), foodnote 13 p. 86. Henry wrote the same about Wallachia

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. p. 71. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1963). Angles and Britons: O'Donnell Lectures. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. English and Welsh, an O'Donnell Lecture delivered at Oxford on Oct. 21, 1955.

- ↑ Gilleland, Michael (12 December 2007). "Laudator Temporis Acti: More on the Etymology of Walden". Laudator Temporis Acti website. Michael Gilleland. http://laudatortemporisacti.blogspot.com/2007/12/more-on-etymology-of-walden.html. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Davies, John (1990). A History of Wales (First ed.). London: Penguin Group (published 1993). p. 69. ISBN 0-713-99098-8, A History of Wales, 400–800.

- ↑ Lloyd, John Edward (1911). "Note to Chapter VI, the Name "Cymry"". A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. I (Second ed.). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. (published 1912). pp. 191 – 192. http://books.google.com/books?id=NYwNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA191

- ↑ Phillimore, Egerton (1891). "Note (a) to The Settlement of Brittany". In Phillimore, Egerton. Y Cymmrodor. XI. London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion. 1892. pp. 97 – 101. http://books.google.com/books?id=M35QO0vor-EC&pg=PA97

- ↑ Davies, John (1990). A History of Wales (First ed.). London: Penguin Group (published 1993). p. 71. ISBN 0-713-99098-8, A History of Wales, 400–800. The poem contains the line: 'Ar wynep Kymry Cadwallawn was'.

- ↑ Hubert, Henri; Mauss, Marcel (1934). "What the Celts Were". The Rise of the Celts. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner. p. 25 – 26. ISBN 0-8196-0183-7

- ↑ Koch, John T., ed (2005). "Cimbri and Teutones". Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABL-CLIO (published 2006). p. 437. ISBN 9781851094400

- ↑ "Channel 4 - News - Red Lady skeleton 29,000 years old". Channel 4 website. Channel 4 - News. 30 October 2007. http://www.channel4.com/news/articles/science_technology/red+lady+skeleton+29000+years+old/979762. Retrieved 30 October 2008 : see Red Lady of Paviland.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. pp. 4-6. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ "Overview: From Neolithic to Bronze Age, 8000–800 BC (Page 1 of 6)". BBC History website. BBC. 5 September 2006. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/british_prehistory/overview_british_prehistory_01.shtml. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "GGAT 72 Overviews" (PDF). A Report for Cadw by Edith Evans BA PhD MIFA and Richard Lewis BA. Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust. 2003. p. 47. http://www.ggat.org.uk/cadw/cadw_reports/pdfs/GGAT%2072%20Overviews.pdf. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ↑ "Stones of Wales - Pentre Ifan Dolmen". Stone Pages website. Paola Arosio/Diego Meozzi. 2003. http://www.stonepages.com/wales/pentreifan.html. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ↑ "Stones of Wales - Bryn Celli Ddu Burial chamber". Stone Pages website. Paola Arosio/Diego Meozzi. 2003. http://www.stonepages.com/wales/bryncelliddu.html. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ↑ "Parc le Breos Burial Chamber; Parc CWM Long Cairn". The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales website. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. 2006. http://www.coflein.gov.uk/pls/portal/coflein.w_details?inumlink=6052756. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ↑ "BBC Wales - History - Themes Prehistoric Wales: The Stone Age". BBC Wales website. BBC. 2008. http://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/history/sites/themes/periods/prehistoric02.shtml. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ↑ "Your guide to Stonehenge, the World's Favourite Megalithic Stone Circle". Stonehenge.co.uk website. Longplayer SRS Ltd (trading as www.stonehenge.co.uk). 2008. http://www.stonehenge.co.uk/history.htm. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑ "O'Donnell Lecture 2008 Appendix". http://www.wales.ac.uk/Resources/Documents/Research/ODonnell.pdf.

- ↑ Koch, John (2009). Tartessian: Celtic from the Southwest at the Dawn of History in Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica 9 (2009). Palaeohispanica. pp. 339–351. http://ifc.dpz.es/recursos/publicaciones/29/54/26koch.pdf. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ↑ Koch, John. "New research suggests Welsh Celtic roots lie in Spain and Portugal". http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=2146413465. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Karl, Guerra, McEvoy, Bradley; Oppenheimer, Rrvik, Isaac, Parsons, Koch, Freeman and Wodtko (2010). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Oxbow Books and Celtic Studies Publications. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4. http://www.oxbowbooks.com/bookinfo.cfm/ID/88298//Location/DBBC.

- ↑ "Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe". University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies and Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford. http://www.oxbowbooks.com/pdfs/books/Celtic%20West%20conf.pdf. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. p. 17. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. pp. 26 & 27. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ For the original Middle Welsh text see, Ifor Williams (ed.), Breuddwyd Maxen (Bangor, 1920). Discussion of the tale and its context in M.P. Charlesworth, The Lost Province (Gregynog Lectures series, 1948, 1949).

- ↑ Ancient Britain Had Apartheid-Like Society, Study Suggests. National Geographic News. 21 July 2006.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Davies, John (1993). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ David Hill and Margaret Worthington, Offa's Dyke: history and guide, Tempus, 2003, ISBN 0-7524-1958-7

- ↑ The earliest instance of Lloegyr occurs in the early 10th century prophetic poem Armes Prydein. It seems comparatively late as a place name, the nominative plural Lloegrwys, "men of Lloegr", being earlier and more common. The English were sometimes referred to as an entity in early poetry (Saeson, as today) but just as often as Eingl (Angles), Iwys (Wessex-men), etc. Lloegr and Sacson became the norm later when England emerged as a kingdom. As for its origins, some scholars have suggested that it originally referred only to Mercia – at that time a powerful kingdom and for centuries the main foe of the Welsh. It was then applied to the new kingdom of England as a whole (see for instance Rachel Bromwich (ed.), Trioedd Ynys Prydein, University of Wales Press, 1987). "The lost land" and other fanciful meanings, such as Geoffrey of Monmouth's monarch Locrinus, have no etymological basis. (See also Discussion, article 40)

- ↑ Davies, John (1993). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. p. 100. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ Davies, John (1993). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. p. 128. ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- ↑ "Tribute to lost Welsh princess", bbc.co.uk date 12 June 2000, URL retrieved on 5 March 2007

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 Davies (2008) p. 392

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 Davies (2008) p. 393

- ↑ Davies (2008) p. 818

- ↑ 'the most Welsh of Welsh industries' attributed to historian A. H. Dodd. Davies (2008) p. 819

- ↑ Wales - the first industrial nation of the World National Museum of Wales

- ↑ "BBC - Liverpool - Features - Flooding Apology". BBC website. BBC Wales. 19 October 2005. http://www.bbc.co.uk/liverpool/content/articles/2005/10/17/feature_welsh_reservoir_feature.shtml. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ↑ Gwynfor, Evans (2000). The Fight for Welsh Freedom. Y Lolfa Cyf., Talybont. p. 152. ISBN 0 86243 515 32.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Clews, Roy (1980). To Dream of Freedom - The story of MAC and the Free Wales Army. Y Lolfa Cyf., Talybont. pp. 15, 21 & 26–31. ISBN 0 86243 586 2.

- ↑ "BBC News - Wales - Mid Wales - Dam graffiti wall set to be saved". BBC News website (BBC News). 17 October 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/mid/6056566.stm. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ↑ "Wales | Details of Labour-Plaid Agreement". BBC News. 27 June 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/wales/6246428.stm. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "UK Parliament -Parliament's role". United Kingdom Parliament website. United Kingdom Parliament. 29 June 2009. http://www.parliament.uk/about/how/role.cfm. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ↑ "Welsh Assembly Government:Devolution timeline". Welsh Assembly Government website. Welsh Assembly Government. 2009. http://wales.gov.uk/about/10years/timeline/?lang=en. Retrieved 31 August 2009.