Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis

| General The Most Honourable The Marquess Cornwallis KG |

|

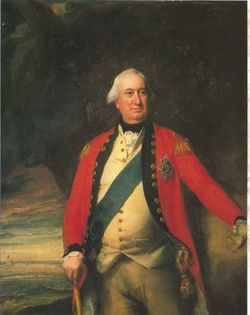

The Marquess Cornwallis, painted by John Singleton Copley. |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 12 September 1786 – 28 October 1793 |

|

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Sir John Macpherson, Bt As Acting Governor-General |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Shore |

| In office 30 July 1805 – 5 October 1805 |

|

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Mornington |

| Succeeded by | Sir George Barlow, Bt As Acting Governor-General |

|

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

|

|

| In office 14 June 1798 – 27 April 1801 |

|

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | The Earl Camden |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Hardwicke |

|

Member of Parliament

for Wye |

|

| In office January 1760 – 23 June 1762 |

|

|

|

|

| Born | 31 December 1738 Grosvenor Square Mayfair, London Great Britain |

| Died | 5 October 1805 (aged 66) Gauspur, Ghazipur Kingdom of Kashi |

| Birth name | Charles Cornwallis |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Eton College Clare College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Military officer, Colonial administrator |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1757 – 1805 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Seven Years' War American War of Independence Third Mysore War Irish Rebellion of 1798 |

| Awards | Knight Companion of The Most Noble Order of the Garter |

| Monarch | George II George III |

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis KG (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as The Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army officer and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom he is best remembered as one of the leading British generals in the American War of Independence. His 1781 surrender to a combined American-French force at the Siege of Yorktown ended significant hostilities in North America, but is often incorrectly considered the end of the war; in fact, it continued for a further two years.[1] Despite this defeat, he retained the confidence of successive British governments and continued to enjoy an active career. In India, where he served two terms as governor general, he is remembered for promulgating the Permanent Settlement. As Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, he argued for Catholic emancipation and oversaw the response to the 1798 Irish Rebellion and a French invasion of Ireland, and was instrumental in the Union of Great Britain and Ireland.

Contents |

Early life

Cornwallis was the eldest son of Charles Cornwallis, 5th Baron Cornwallis (later 1st Earl Cornwallis) (29 March 1700 – 23 June 1762), in the Howells, near Bristol) and was born at Grosvenor Square in London, England, even though his family's estates were in Kent.

The Cornwallis family was established at Brome Hall, near Eye, in Suffolk, in the 14th century, and its members occasionally represented the county in the House of Commons over the next three hundred years. Frederick Cornwallis, created a Baronet in 1627, fought for King Charles I, and followed King Charles II into exile. He was made Baron Cornwallis, of Eye in the County of Suffolk, in 1661, and his descendants by fortunate marriages increased the importance of the family.

He was extremely well-connected. His mother, Elizabeth Townshend (died 1 December 1785), was the daughter of the 2nd Viscount Townshend and a niece of the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole. His father was created Earl Cornwallis, Viscount Cornwallis and Viscount Brome in 1753, at which point he was styled Viscount Brome. His brother was Admiral Sir William Cornwallis. An uncle, Frederick, was Archbishop of Canterbury and another uncle, Edward, was a leading colonist in Canada

Early military career

Cornwallis was educated at Eton College and Clare College, Cambridge. While at Eton, he received an injury to his eye by an accidental blow while playing hockey, from Shute Barrington, later Bishop of Durham.[2] He obtained his first commission as Ensign in the 1st Foot Guards, on 8 December 1757. His military education then commenced, and after travelling on the continent with a Prussian officer, Captain de Roguin, he studied at the military academy of Turin. He also became a Member of Parliament in January 1760, entering the House of Commons for the village of Wye in Kent. He succeeded his father as 2nd Earl Cornwallis in 1762, which resulted in his elevation to the House of Lords.

Seven Years War

Throughout the Seven Years' War, Lord Cornwallis served four terms in different posts in Germany, interspersed with trips home. As soon as heard that British troops were being sent to Germany in 1758, he hurried to join them without waiting for orders from home and secured an appointment as a staff officer to Lord Granby.

A year later, he participated at the Battle of Minden, a major battle that prevented a French invasion of Hanover. After the battle, he purchased a captaincy in the 85th Regiment of Foot. In 1761, he served with the 11th Foot and was promoted to Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel. He led his regiment in the Battle of Villinghausen on 15 – 16 July 1761, and was noted for his gallantry. In 1762 his regiment was involved in heavy fighting during the Battle of Wilhelmsthal. A few weeks later they defeated Saxon troops at the Battle of Lutterberg and ended the year by participating in the Siege of Cassel.

Following the 1763 Treaty of Paris he returned to Britain, where he became a political protege of the leading Whig magnate, and future Prime Minister, Lord Rockingham.[3]

He became colonel of the 33rd Regiment of Foot in 1766. The same year he voted along with five other peers against the Stamp Act, out of sympathy with the American colonists.[4] He maintained a strong degree of support for the colonists during the tensions and crisis that led to the American War of Independence.

American War of Independence

After the opening skirmishes of the war took place around Boston, Cornwallis put his previous misgivings aside and sought active service. His participation in the war began with his service as second in command to Henry Clinton. Cornwallis, along with several other senior officers, was promoted shortly before leaving for the conflict.[5] Clinton's forces arrived in North America in May 1776 at Cape Fear, North Carolina. These forces then shifted south and participated in the first Siege of Charleston in June 1776. They were unable to make a breakthrough and eventually withdrew.

New York campaign

After the failure of this siege, Clinton and Cornwallis transported their troops north to serve under William Howe in the campaign for New York City. During this campaign, Cornwallis, still serving under Clinton, fought with distinction in the Battle of Long Island, participated in the Battle of White Plains, and played a supporting role in the capture of Fort Washington. Cornwallis was then given an independent command in which he captured Fort Lee and pursued George Washington's forces. While Washington withdrew all the way across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania, Cornwallis had only been authorised to advance as far as New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Trenton and Princeton

After the New York City campaign and the subsequent occupation of New Jersey by the British army, Cornwallis prepared to leave for England as the army moved into winter quarters. However, as Cornwallis was preparing to embark in December 1776, Washington launched his surprise attack on Trenton. In response, Cornwallis' leave was cancelled and Howe ordered him to deal with Washington. Since Clinton was in England at this time, Cornwallis served directly under Howe.

Cornwallis gathered together garrisons scattered across New Jersey and moved them to Trenton. On 2 January 1777, he confronted Washington's army, which was positioned near Assunpink Creek. In the resulting Second Battle of Trenton, Cornwallis unsuccessfully attacked Washington's position late in the afternoon. Cornwallis prepared his troops to continue the assault of Washington's position the next day. During the night, however, Washington's forces slipped around his, and attacked the British outpost at Princeton. While the credit for the success of the Continental Army's disengagement from Cornwallis is due to Washington's use of deception, including maintaining blazing campfires and keeping up sounds of camp activity, Cornwallis contributed by failing to send out patrols to monitor the Continental Army's activities.

After the battle of Princeton, Washington's forces moved north toward Morristown and the British forces withdrew from most of New Jersey, taking up winter quarters in garrisons centred on New Brunswick and Perth Amboy. During the winter, Cornwallis' troops participated in numerous raids during the forage war in an attempt to deny the Continental forces access to supplies and provide for themselves. In early spring, Cornwallis led a successful attack on Benjamin Lincoln's garrison at Bound Brook on 13 April 1777. However, these engagements had no long-term impact as Howe had decided to withdraw his forces back towards New York City in preparation for a campaign to Philadelphia.

Philadelphia campaign

Cornwallis also participated as a field commander in General Howe's Philadelphia campaign of 1777. Howe intended to launch an offensive against Philadelphia, hoping to end the war at a stroke. Cornwallis was given command of the army's light infantry. At the Battle of Brandywine on 11 September 1777, Cornwallis was responsible for the flanking movement that ultimately forced the American forces from their position. Cornwallis also played an important role in the Battle of Germantown on 4 October and the capture of Fort Mercer in New Jersey on 20 November. With the army in winter quarters in Philadelphia, Cornwallis took his long-delayed leave to England carrying home important information.

Cornwallis returned to Philadelphia to again serve as second-in-command to Henry Clinton, who replaced William Howe as the British commander-in-chief. After the surrender of John Burgoyne's army at Saratoga and the entry of France into the war, the British regarded the occupation of the city as a drain of valuable troops and resources needed elsewhere.[6] Cornwallis commanded the rearguard during the overland withdrawal from Philadelphia to New York City and played an important role in the Battle of Monmouth on 28 June 1778. After a surprise attack on the British rearguard, Cornwallis launched a counter-attack which checked the enemy advance. In November, 1778, Cornwallis once more returned to England to be with his ailing wife, Jemima, who died in February 1779.

Southern theatre

Cornwallis returned to America in July, 1779, where he was to play a central role as the lead commander of the British "Southern strategy". At the end of 1779, Clinton and Cornwallis transported a large force south and initiated the second siege of Charleston during the spring of 1780, which resulted in the surrender of the Continental forces under Benjamin Lincoln. After the siege of Charleston and the destruction of Abraham Buford's Virginia regiments at Waxhaw, Clinton returned to New York, leaving Cornwallis in command in the south.

Cornwallis was faced with the task of seeking an outright victory over the enemy, something General Howe had failed to do in the north in spite of winning several battles.[7] The forces he was given to accomplish this were limited by the necessity of keeping a large British force in New York under Clinton to shadow Washington. Cornwallis was told by his superiors to utilise the support of Loyalists, who were believed to be more numerous in the southern colonies. Personally, Cornwallis favoured a bolder and more aggressive approach than either Clinton or Howe had.[7] He also expanded on an existing British policy of recruiting black slaves, who overwhelmingly favoured the Loyalist cause, as scouts, laborers and soldiers.

In August 1780 Cornwallis' forces met a larger but relatively untried army under the command of Horatio Gates at the Battle of Camden, where they inflicted heavy casualties and routed part of the force.[8] This served to effectively clear South Carolina of Continental forces, and was a blow to rebel morale. The victory added to his reputation, though the rout of the American rebels had as much to do with the failings of Gates as it did the skill of Cornwallis. As the opposition to him seemed to melted away, Cornwallis began to advance north into North Carolina while militia activity continued to harass the troops he left in South Carolina. Attempts by Cornwallis to rally Loyalist support were dealt significant blows when a large gathering of them was defeated at Kings Mountain, only a day's march from Cornwallis and his army, and another large detachment of his army was decisively defeated at Cowpens. He then clashed with the rebuilt Continental army under General Nathanael Greene at Guilford Courthouse in North Carolina, winning a Pyrrhic victory with a bayonet charge against a numerically superior enemy.

Cornwallis then moved his forces to Wilmington on the coast to resupply. Cornwallis himself had generally been successful in his battles, but the constant marching and the losses incurred had shrunk and tired out his army. Greene, whose army was still intact after the loss at Guilford Courthouse, shadowed Cornwallis toward Wilmington, but then crossed into South Carolina, where over the course of several months regained control over most of the state.

Cornwallis received dispatches in Wilmington informing him that another British army under Generals William Phillips and Benedict Arnold had been sent to Virginia, so he decided to join forces with them and attack the Continental Army supply bases in Virginia.

Virginia campaign

On arrival in Virginia, Cornwallis took command of Phillips' army. Phillips, a personal friend of Cornwallis, died one week before Cornwallis reached his position at Petersburg.[9] Having marched without informing Clinton of his movements (communications between the two British commanders was by sea and extremely slow, sometimes up to three weeks),[10] he sent word of his northward march and engaged in destroying American supplies in the Chesapeake region.

In March 1781, in response to the threat posed by Arnold and Phillips, General Washington had dispatched Marquis de Lafayette to defend Virginia. The young Frenchman had 3,200 men at his command, but British troops in the state now totalled 7,200.[11] Lafayette skirmished with Cornwallis, avoiding a decisive battle while gathering reinforcements. It was during this period that Cornwallis received orders from Clinton to choose a position on the Virginia Peninsula—referred to in contemporary letters as the "Williamsburg Neck"—and construct a fortified naval post to shelter ships of the line.[12] In complying with this order, Cornwallis put himself in a position to become trapped. With the arrival of the French fleet under the Comte de Grasse and General George Washington's combined French-American army, Cornwallis found himself cut off. After the Royal Navy fleet under Admiral Thomas Graves was defeated by the French at the Battle of the Chesapeake, and the French siege train arrived from Newport, Rhode Island, his position became untenable. He surrendered to General Washington and the French commander, the Comte de Rochambeau, on 19 October 1781.[13] Cornwallis, apparently not wanting to face Washington, claimed to be ill on the day of the surrender, and sent Brigadier General Charles O'Hara in his place to formally surrender his sword. Washington had his second-in-command, Benjamin Lincoln, accept Cornwallis' sword.

Return to Britain

In 1782 Cornwallis was exchanged for Henry Laurens, who had been held in London and was considered a prisoner of equal rank.[14] He returned to Britain with Benedict Arnold, and they were cheered when they landed in England on 21 January 1782.[15] His tactics in America, especially during the southern campaign, were a frequent subject of criticism by his political enemies in London. However Cornwallis retained the confidence of King George III and the British government.

His surrender did not mark the end of the war, though it ended major fighting in the American theatre. In spite of the ongoing conflict, Cornwallis was not immediately considered for another command, and the war came to an end in 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris.

In August 1785 he attended manoeuvres in Prussia along with the Duke of York where they encountered Frederick the Great and de Lafayette.[16]

Governor-General of India

In 1786 Cornwallis was made a Knight Companion of The Most Noble Order of the Garter. The same year he was appointed Governor-General and commander in chief in India. He instituted land reforms and reorganised the British army and administration. He was increasingly aligned with the government of William Pitt, writing home about his relief at King George III's recovery from illness, which had prevented the radical opposition led by Charles James Fox from taking power.[17]

Conflict with Mysore

After the British had repeated conflicts with Tipu Sultan, the powerful sultan of Mysore, Cornwallis finally besieged his capital, Seringapatam, and compelled him to agree to a treaty in which Mysore's territory was significantly reduced. For his success, Cornwallis was created Marquess Cornwallis in 1792.[18] He returned to England the following year, and was succeeded by Sir John Shore.

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Cornwallis was made Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and Commander-in-Chief, Ireland in June 1798,[19] after the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 between republican United Irishmen and the government. His appointment was greeted unfavourably by the Irish elite, who preferred his predecessor Lord Camden, and suspected he had liberal sympathies with the predominantly Catholic rebels. However, he struck up a good working relationship with Lord Castelreagh, the Chief Secretary for Ireland.

In his combined role as both Viceroy and Commander-in-Chief Cornwallis oversaw the defeat of both the Irish rebels and a French invasion force led by General Humbert that landed in Connaught in August 1798. Panicked by the landing, and the British defeat at the Battle of Castlebar, thousands of reinforcements were despatched to Ireland swelling his forces to 60,000.[20] The French invaders were defeated and forced to surrender at the Battle of Ballinamuck. During the autumn Cornwallis secured government control over the island, and organised the suppression of the remaining supporters of the United Irish movement.

He was also responsible for ordering the Military Road in Wicklow built, to root out rebels to the south of Dublin. It was part of a lengthy operation in mopping up the last areas of resistance, which lasted until Cornwallis' departure in 1801.

Cornwallis was also instrumental in securing passage in 1800 of the Act of Union by the Parliament of Ireland, which resulted in the creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The process, which essentially required the buying of votes in the Parliament of Ireland through patronage and the granting of peerages, was one that Cornwallis found quite distasteful. Although Cornwallis recognised that the union with Ireland was unlikely to succeed without Catholic emancipation, he and William Pitt were unable to move King George on the subject, with the result that Pitt's government fell, and Cornwallis resigned his offices, returning to London in May 1801.

Treaty of Amiens

Cornwallis negotiated the terms of the Treaty of Amiens, which he signed on behalf the United Kingdom on 25 March 1802 with Napoleon. He and General Charles O'Hara (his second in command from Charleston to Yorktown) have the rare distinction of dealing with both Washington and Napoleon. The treaty ended the War of the Second Coalition, made possible by financial pressure and the resignation of William Pitt on 16 February 1801. Henry Addington succeeded Pitt, and appointed Cornwallis Minister Plenipotentiary. The British negotiators in Paris were led by Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool. Despite their efforts, the peace soon broke down, and war recommenced.

Death

He was reappointed Governor-General of India in 1805, but on 5 October, shortly after arriving, died of a fever at Gauspur in Ghazipur, at that time in the Varanasi kingdom. Cornwallis was buried there, overlooking the Ganges River, where his memorial continues to be maintained by the Government of India.

Legacy

Today Cornwallis is remembered primarily as the British commander who surrendered at Yorktown. Because of the enormous impact the siege—and its result—had on American history he is still fairly well-known in the United States, and is often referenced in popular culture. In the 1835 novel Horse-Shoe Robinson by John Pendleton Kennedy, a historical romance set against the background of the Southern campaigns in the American War of Independence, Cornwallis appears and interacts with the fictional characters in the book. He is depicted as courtly in manner, but tolerant or even supportive of brutal practices against those found deficient among his own forces and against enemy prisoners. In the 2000 film The Patriot about the events leading up to Yorktown, Cornwallis was portrayed by English actor Tom Wilkinson.[21]

In Ireland he achieved a notoriety that lasts to this day because of the execution of rebel prisoners in Ballinalee after the Battle of Ballinamuck. In the village, in the north Leinster county of Longford, the site of the executions is known as Bully's Acre.

In India he is remembered for his victory against Tipu Sultan in Nandi Hills in the Mysore war and promulgation of revenue and judicial acts. Cornwallis is also known in India for his brutality and cunning.

Fort Cornwallis, founded in 1786 in George Town, Prince of Wales Island (now the island part of the Malaysian state of Penang), is named after General Cornwallis.

He also has a building named after him at the University of Kent, Canterbury and boarding houses at The Royal Hospital School and Culford School in Suffolk. A large statue of Cornwallis can be seen in St. Paul's Cathedral, London.

Dates of rank

| Ensign, British Army: 1756 |

| Captain, British Army: 1759 |

| Lieutenant Colonel, British Army: 1761 |

| Colonel, British Army: 1766 |

| Major General, British Army: 1775 |

| Lieutenant General, British Army: 1777 |

| General, British Army: 1793 |

Bibliography

Primary documents/sources

- Public Record Office, United Kingdom: Cornwallis Papers, Ref: 30/11/1-66

- The Correspondence of Charles, First Marquis Cornwallis, Vol. 1, 1859, ed. Ross.

Secondary sources

- Adams, R: "A View of Cornwallis's Surrender at Yorktown", American Historical Review, Vol. 37, No. 1 (October, 1931), pp. 25–49,

- Bicheno, H: Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolutionary War, London, 2003

- Buchanan, J: The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution and the Carolinas, New York, 1997

- Clement, R: "The World Turned Upside down At the Surrender of Yorktown", Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 92, No. 363 (January - March, 1979), pp. 66–67

- Duffy, Christopher. Frederick the Great: A Military Life. London, 1985.

- Ferling, J: The World Turned Upside Down: The American Victory in the War of Independence, London, 1988

- Harvey, R: A Few Bloody Noses: The American War of Independence, London, 2001

- Harvey, R: War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France 1789-1815, London, 2007

- Hibbert, C: Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution Through British Eyes, London, 2001

- Hibbert, C: King George III: A Personal History,

- Mackesy, P: The War for America, London, 1964

- Pakenham, H: The Year of Liberty: The Great Irish Rebellion of 1798, London 1969

- Peckham, H:The War for Independence, A Military History, Chicago, 1967

- Unger, H.G:Lafayette, New York, 2002

- Weintraub, S: Iron Tears, Rebellion in America 1775-1783, London, 2005

- Wickwire, F: Cornwallis, The American Adventure, Boston, 1970

References

- ↑ Harvey p.526

- ↑ Cornwallis, Charles, Viscount Brome in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- ↑ Bicheno p.168

- ↑ Weintraub p.34

- ↑ Weintraub p.62

- ↑ Harvey p.377

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Harvey p.467

- ↑ Harvey p.424-427

- ↑ Wickwire, Cornwallis, The American Adventure, 1970

- ↑ Cornwallis Papers, Public Record Office the dates of receipt throughout this period of the war are usually two to three weeks after the date of dispatch

- ↑ Cornwallis, C, An Answer to the Narrative of Sir Henry Clinton, appended table.

- ↑ Clinton to Cornwallis, 15 June 1781, Cornwallis Papers, Public Record Office

- ↑ Unger pp.158-9

- ↑ Bicheno p.265

- ↑ Weintraub p.315

- ↑ Duffy p.279-80

- ↑ Hibbert p.302

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 13450, p. 635, 14 August 1792.

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 15029, p. 523, 12 June 1798.

- ↑ Harvey. War of Wars. p.224-5

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0187393/

External links

- The Peerage profile of Cornwallis

- Archival material relating to Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis listed at the UK National Register of Archives

- Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis at Find a Grave

- letters of Cornwallis from the American Revolution

- 1781: The World Turned Upside Down

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Viscount Bolingbroke |

Lord of the Bedchamber 1765 |

Succeeded by Not replaced |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by John MacPherson |

Governor-General of India 1786–1793 |

Succeeded by The Lord Teignmouth |

| Preceded by The Duke of Richmond |

Master-General of the Ordnance 1795–1801 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Chatham |

| Preceded by The Marquess Camden |

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland 1798–1801 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Hardwicke |

| Preceded by The Marquess Wellesley |

Governor-General of India 1805 |

Succeeded by Sir George Barlow, Bt |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by The Lord Monson |

Justice in Eyre South of the Trent 1767–1769 |

Succeeded by The Lord Grantley |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Vacant

Title last held by

The Marquess of Stafford |

British Plenipotentiary to France 1801–1802 |

Succeeded by The Lord Whitworth |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Robert Sloper |

Commander-in-Chief, India 1786–1793 |

Succeeded by Sir Robert Abercromby |

| Preceded by The Viscount Lake |

Commander-in-Chief, Ireland 1798–1801 |

Succeeded by William Medows |

| Preceded by The Viscount Lake |

Commander-in-Chief, India 1805 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Lake |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The Lord Berkeley of Stratton |

Constable of the Tower Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets 1771–1784 |

Succeeded by Lord George Lennox |

| Preceded by Lord George Lennox |

Constable of the Tower Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets 1784–1805 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Moira |

| Peerage of Great Britain | ||

| New creation | Marquess Cornwallis 1792–1805 |

Succeeded by Charles Cornwallis |

| Preceded by Charles Cornwallis |

Earl Cornwallis 1762–1805 |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||