Contrabassoon

|

|

| Other names | Double bassoon, double-bassoon |

|---|---|

| Classification | (double reed) |

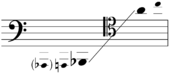

| Playing range | |

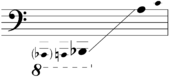

The contrabassoon sounds one octave lower than written. Sounding: |

|

| Related instruments | |

|

|

The contrabassoon, also known as the double bassoon or double-bassoon, is a larger version of the bassoon, sounding an octave lower. Its technique is similar to its smaller cousin, with a few notable differences.

Contents |

Differences to the bassoon

The reed is considerably larger, at 65–75 mm in total length as compared to 53–58 mm for most bassoon reeds. Fingering is slightly different, particularly at the register change and in the extreme high range. The instrument is twice as long, curves around on itself twice, and, due to its weight and shape, is supported by an endpin rather than a seat strap. Additional support is sometimes given by a strap around the player's neck. A wider hand position is also required, as the primary finger keys are widely spaced. The contrabassoon has a water key to expel condensation and a tuning slide for gross pitch adjustments. The instrument comes in a few pieces (plus bocal); in some models, it cannot be disassembled without a screwdriver. Sometimes, however, the bell can be detached, and in the case of instruments with a low A extension, the instrument often comes in two parts.

Range

With a range beginning at B♭0 (extending down a half-step to the lowest note on the piano on instruments with the low A extension or to A♭ in one example), and extending up just over three octaves, the contrabassoon is the second deepest available sound in an orchestra, after the tuba. Accordingly, the instrument is notated an octave above sounding pitch in bass clef, with tenor or even (rarely) treble clef called for in high passages. The instrument has a high range extending to middle C, but the top fifth is rarely used. Tonally, it sounds much like the bassoon except for a distinctive organ pedal quality in the lowest octave of its range which provides a solid underpinning to the orchestra. Although the instrument can have a distinct 'buzz', which becomes almost a clatter in the extreme low range, this is nothing more than a variance of tone quality which can be remediated by appropriate reed design changes. While prominent in solo and small ensemble situations, the sound can be completely obscured in the volume of the full orchestra.

History

The contrabassoon was developed in the mid-17th century; the oldest surviving instrument, which came in four parts and had only three keys, was built in 1714. It was around that time that the contrabassoon began gaining acceptance in church music, and by the end of the 18th century it was making its way into British military bands. However, until the late 19th century, the contrabassoon typically had a weak tone and poor intonation. For this reason the contrabass woodwind parts often were scored for, and contrabassoon parts were often played on, contrabass sarrusophone or, less frequently, reed contrabass, until improvements to the contrabassoon by Heckel in the late 19th century secured its place as the standard double reed contrabass. For more than a century, between 1880 and 2000, the contrabassoon of Heckel’s design remained relatively unchanged. A few keys were added during this time, most notably an upper vent key near the bocal socket, a tuning slide, and a few key linkages to facilitate technical passages.

Manufacturers

Currently, contrabassoons are made by W. Schreiber, Heckel, Fox, Wolf, Moennig, Moosman, Püchner, Adler, Amati and Mollenhauer (and possibly others). In 2001, Fox introduced a new model of the contrabassoon with a completely revised system of register keys (octave keys), designed by Arlen Fast of the New York Philharmonic, and built by Chip Owen at Fox. It addressed a variety of problems with the standard system, including poor articulation, and weak and uneven tone in the upper registers of the instrument. This design was granted a patent (#6,765,138) in 2004. The changes introduced with this system have greatly improved the playing characteristics of the contrabassoon and have extended its effective range upwards. It was quickly adopted by the contrabassoon players in the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra and the National Symphony, as well as others. The Kalevi Aho Concerto for Contrabassoon (2005) was written for Lewis Lipnick of the National Symphony, playing on a Fast-System Fox contrabassoon. It became the first contrabassoon concerto to be recorded and released by a major record label, BIS Records.

Current use

Most orchestras use one contrabassoonist, either as a primary player or a bassoonist who doubles, as do a large number of symphonic bands and wind ensembles. In some rare circumstances they are found in wind quintets.

While relatively rare, the instrument is most frequently found in larger symphonies, particularly those of Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, and Dmitri Shostakovich. The first composer to write a separate contrabassoon part in a symphony was Beethoven, in his Fifth Symphony (1808), although Bach, Handel (in his Music for the Royal Fireworks), Haydn, and Mozart occasionally used it in other genres. Composers have often used the contrabassoon to comical or sinister effect by taking advantage of its clumsiness and its sepulchral rattle, respectively. A clear example of its sound can be heard in Paul Dukas' The Sorcerer's Apprentice.

Some modern composers such as Gunther Schuller, Donald Erb, Michael Tilson Thomas, Kalevi Aho, and Daniel Dorff have written concertos for this instrument. Graham Waterhouse set Aztec Ceremonies for contrabassoon and piano. Orchestrally, the contrabassoon is featured in Maurice Ravel's Mother Goose Suite, and Piano Concerto for the Left Hand.

It can also be clearly heard providing the bass line in the brief "Janissary band" section of the fourth movement of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, just prior to the tenor solo.

Pitch

The contrabassoon acts as the lowest voice of the woodwind ensemble, though the orchestral tuba can reach lower pitches. It is also often used to support other mixed orchestrations, such as doubling the bass trombone or tuba at the octave. Frequent exponents of such scoring were Brahms and Mahler. Haydn also used this instrument in both of his oratorios, The Creation and The Seasons. In these works the part for the contrabassoon and the bass trombone are mostly, but not always, identical.

Notable contrabassoons

Prof. Dr. Werner Schulze of Austria owns a contrabassoon with an extension to A♭0, the note a half step below the lowest note on the piano.

Recently, the instrument makers Guntram Wolf and Benedikt Eppelsheim have collaborated in the reworking of the contrabassoon, resulting in a new instrument they call the Contraforte. It has a larger bore, as well as larger tone holes, resulting in a slightly different tone from a normal contrabassoon. The Wolf Contraforte contains a natural extension down to A0, and several other features such as silent key movement and an automatic water drain.

Notable Performers

One of the few contrabassoon soloists in the world is Susan Nigro [1] who lives and works in and around Chicago. Besides occasional gigs with orchestras and other ensembles (including regular substitute with the Chicago Symphony), her main work is as soloist and recording artist. Many works have been written specifically for her , and she has several CDs.

Floridian Henry Skolnick has also performed and toured internationally on the insturment.[2]

References

- ↑ www.bigbassoon.com/

- ↑ http://www.innova.mu/notes/520.htm.

- Raimondo Inconis, Il controfagotto, storia e tecnica, ed. Ricordi, Milano (1984–2004)

External links

- A contrabassoon discography

- Internet Contrabassoon Resource

- Susan Nigro's website

- Susan Nigro interview by Bruce Duffie

See also

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||