Continent

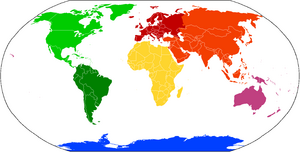

A continent is one of several large landmasses on Earth. They are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, with seven regions commonly regarded as continents – they are (from largest in size to smallest): Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia.[1]

Plate tectonics is the geological process and study of the movement, collision and division of continents, earlier known as continental drift.

The term the Continent may also refer to Continental Europe, i.e., excluding the British Isles.[2]

Contents |

Definitions and application

Conventionally, "Continents are understood to be large, continuous, discrete masses of land, ideally separated by expanses of water."[3] Many of the seven most commonly recognized continents identified by convention are not discrete landmasses separated by water. The criterion 'large' leads to arbitrary classification: Greenland, with a surface area of 2,166,086 square kilometres (836,330 sq mi) is considered the world's largest island, while Australia, at 7,617,930 square kilometres (2,941,300 sq mi) is deemed to be a continent. Likewise, the ideal criterion that each be a continuous landmass is often disregarded by the inclusion of the continental shelf and oceanic islands, and contradicted by classifying North and South America as one continent; and/or Asia, Europe and Africa as one continent, with no natural separation by water. This anomaly reaches its extreme if the continuous land mass of Europe and Asia is considered to constitute two continents. The Earth's major landmasses are washed upon by a single, continuous World Ocean, which is divided into a number of principal oceanic components by the continents and various geographic criteria.[4][5]

Extent of continents

The narrowest meaning of continent is that of a continuous[6] area of land or mainland, with the coastline and any land boundaries forming the edge of the continent. In this sense the term continental Europe is used to refer to mainland Europe, excluding islands such as Great Britain, Ireland, and Iceland, and the term continent of Australia may refer to the mainland of Australia, excluding Tasmania and New Guinea. Similarly, the continental United States refers to the 48 contiguous states in central North America and may include Alaska in the northwest of the continent (the two being separated by Canada), while excluding Hawaii in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

From the perspective of geology or physical geography, continent may be extended beyond the confines of continuous dry land to include the shallow, submerged adjacent area (the continental shelf)[7] and the islands on the shelf (continental islands), as they are structurally part of the continent.[8] From this perspective the edge of the continental shelf is the true edge of the continent, as shorelines vary with changes in sea level.[9] In this sense the islands of Great Britain and Ireland are part of Europe, while Australia and the island of New Guinea together form a continent (sometimes called Sahul or Australia-New Guinea).

As a cultural construct, the concept of a continent may go beyond the continental shelf to include oceanic islands and continental fragments. In this way, Iceland is considered part of Europe and Madagascar part of Africa. Extrapolating the concept to its extreme, some geographers group the Australasian continental plate with other islands in the pacific into one continent called Oceania. This allows the entire land surface of the Earth to be divided into continents or quasi-continents.[10]

Separation of continents

The ideal criterion that each continent be a discrete landmass is commonly disregarded in favor of more arbitrary, historical conventions. Of the seven most commonly recognized continents, only Antarctica and Australia are distinctly separated from other continents.

Several continents are defined not as absolutely distinct bodies but as "more or less discrete masses of land".[11] Asia and Africa are joined by the Isthmus of Suez, and North and South America by the Isthmus of Panama. Both these isthmuses are very narrow in comparison with the bulk of the landmasses they join, and both are transected by artificial canals (the Suez and Panama canals, respectively) which effectively separate these landmasses.

The division of the landmass of Eurasia into the continents of Asia and Europe is an anomaly, as no sea separates them. An alternative view, that Eurasia is a single continent, results in a six-continent view of the world. This view is held by some geographers and is preferred in Russia (which spans Asia and Europe), East European countries and Japan. The separation of Eurasia into Europe and Asia is viewed by some as a residue of Eurocentrism: "In physical, cultural and historical diversity, China and India are comparable to the entire European landmass, not to a single European country. A better (if still imperfect) analogy would compare France, not to India as a whole, but to a single Indian state, such as Uttar Pradesh."[12] However, for historical and cultural reasons, the view of Europe as a separate continent continues in several categorizations.

North America and South America are now treated as separate continents in India, China, and most English-speaking countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Furthermore, the concept of two American continents is prevalent in much of Asia. However, in earlier times they were viewed as a single continent known as America, with this viewpoint remaining common in the United States until World War II.[13] This remains the more common vision in Spain, Portugal and Latin American countries, where they are taught as a single continent. This use is shown in names as the Organization of American States. From the 19th century some people used the term "Americas" to avoid ambiguity with the United States of America. The plurality of this last term suggests that even in the 19th century some considered the New World (the Americas) as two separate continents.

When continents are defined as discrete landmasses, embracing all the contiguous land of a body, then Asia, Europe and Africa form a single continent known by various names such as Afro-Eurasia. This produces a four-continent model consisting of Afro-Eurasia, America, Antarctica and Australia.

When sea levels were lower during the Pleistocene ice age, greater areas of continental shelf were exposed as dry land, forming land bridges. At this time Australia-New Guinea was a single, continuous continent. Likewise the Americas and Afro-Eurasia were joined by the Bering land bridge. Other islands such as Great Britain were joined to the mainlands of their continents. At that time there were just three discrete continents: Afro-Eurasia-America, Antarctica, and Australia-New Guinea.

Number of continents

There are numerous ways of distinguishing the continents:

| Models | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

| 7 continents [1][14][15][16][17][18] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 continents [15][19] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 6 continents [20][21] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 5 continents [19][20][21] |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 4 continents [19][20][21] |

|

|

|

|

||||

The seven-continent model is usually taught in China and most English-speaking countries. The six-continent combined-Eurasia model is preferred by the geographic community, Russia, the former states of the USSR, and Japan. The six-continent combined-America model is taught in Latin America, and most parts of Europe including Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. This model may be taught to include only the five inhabited continents (excluding Antarctica)[20][21] — as depicted in the Olympic logo.[22]

The names Oceania or Australasia are sometimes used in place of Australia. For example, the Atlas of Canada names Oceania,[14] as does the model taught in Latin America and Iberia.[23][24]

Area and population

The following table summarises the area and population of each continent using the seven continent model, sorted by decreasing area.

| Continent | Area (km²) | Area (mi²) | Percent of total landmass |

Total population | Percent of total population |

Density People per km² |

Density People per mi² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 43,820,000 | 16,920,000 | 29.5% | 3,879,000,000 | 60% | 86.70 | 224.6 |

| Africa | 30,370,000 | 11,730,000 | 20.4% | 922,011,000 | 14% | 29.30 | 75.9 |

| North America | 24,490,000 | 9,460,000 | 16.5% | 528,720,588 | 8% | 21.0 | 54 |

| South America | 17,840,000 | 6,890,000 | 12.0% | 382,000,000 | 6% | 20.8 | 54 |

| Antarctica | 13,720,000 | 5,300,000 | 9.2% | 1,000 | 0.00002% | 0.00007 | 0.00018 |

| Europe | 10,180,000 | 3,930,000 | 6.8% | 731,000,000 | 11% | 69.7 | 181 |

| Australia | 9,008,500 | 3,478,200 | 5.9% | 22,000,000 | 0.5% | 3.6 | 9.3 |

The total land area of all continents is 148,647,000 square kilometres (57,393,000 sq mi), or 29.1% of earth's surface (510,065,600 square kilometres / 196,937,400 square miles).

Highest and lowest points

The following table lists the seven continents with their highest and lowest points on land, sorted in decreasing highest points.

| Continent | Highest point | Height (m) | Height (ft) | Country or territory containing highest point | Lowest point | Depth (m) | Depth (ft) | Country or territory containing lowest point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | Mount Everest | 8,848 | 29,029 | Dead Sea | -422 | −1,384.5 | ||

| South America | Aconcagua | 6,960 | 22,830 | Laguna del Carbón | -105 | −344.5 | ||

| North America | Mount McKinley | 6,198 | 20,335 | Trough beneath Jakobshavn Isbræ † | -1,512 | −4,960.6[25] | ||

| Africa | Mount Kilimanjaro | 5,895 | 19,341 | Lake Assal | -155 | −508.5 | ||

| Europe | Mount Elbrus | 5,633 | 18,481 | Caspian Sea | -28 | −91.9 | ||

| Antarctica | Vinson Massif | 4,892 | 16,050 | Bentley Subglacial Trench † | -2,540 | −8,333.3 | ||

| Oceania | Mount Wilhelm | 4,509 | 14,793 | Lake Eyre | -15 | −49.2 |

† The lowest non-submarine bedrock elevations are given for North America and Antarctica. These are covered by kilometers of ice. The lowest exposed points in North America and Antarctica are in Death Valley (-86 m) and on the shore of Deep Lake in the Vestfold Hills (-50 m).

Some sources list the Kuma-Manych Depression (a remnant of the Paratethys) as the geological border between Europe and Asia. This would place Caucasus outside of Europe, thus making Mont Blanc (elevation 4810 m) in the Graian Alps the highest point in Europe - the lowest point would still be the shore of the Caspian Sea.

Other divisions

Aside from the conventionally known continents, the scope and meaning of the term 'continent' may vary. Supercontinents, largely in evidence earlier in the geological record, are landmasses which comprise more than one craton or continental core. These have included Laurasia, Gondwana, Vaalbara, Kenorland, Columbia, Rodinia, and Pangaea.

Certain parts of continents are recognized as subcontinents, particularly those on different tectonic plates to the rest of the continent. The most notable examples are the Indian subcontinent and the Arabian Peninsula. Greenland, generally reckoned as the world's largest island on the northeastern periphery of the North American Plate, is sometimes referred to as a subcontinent. Where the Americas are viewed as a single continent (America), it is divided into two subcontinents (North America and South America)[26][27][28] or various regions.[29]

Some areas of continental crust are largely covered by the sea and may be considered submerged continents. Notable examples are Zealandia, emerging from the sea primarily in New Zealand and New Caledonia, and the almost completely submerged Kerguelen continent in the southern Indian Ocean.

Some islands lie on sections of continental crust that have rifted and drifted apart from a main continental landmass. While not considered continents because of their relatively small size, they may be considered microcontinents. Madagascar, the largest example, is usually considered an island of Africa but has been referred to as "the eighth continent".

In addition, a number of mythical continents exist: perhaps the most notable is Atlantis, and also Hyperborea, Thule, and Lemuria.

History of the concept

Early concepts of the Old World continents

The first distinction between continents was made by ancient Greek mariners who gave the names Europe and Asia to the lands on either side of the waterways of the Aegean Sea, the Dardanelles strait, the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus strait and the Black Sea.[30] The names were first applied just to lands near the coast and only later extended to include the hinterlands.[31] But the division was only carried through to the end of navigable waterways and "... beyond that point the Hellenic geographers never succeeded in laying their finger on any inland feature in the physical landscape that could offer any convincing line for partitioning an indivisible Eurasia ..."[30]

Ancient Greek thinkers subsequently debated whether Africa (then called Libya) should be considered part of Asia or a third part of the world. Division into three parts eventually came to predominate.[32] From the Greek viewpoint, the Aegean Sea was the center of the world; Asia lay to the east, Europe to the west and north and Africa to the south.[33] The boundaries between the continents were not fixed. Early on, the Europe–Asia boundary was taken to run from the Black Sea along the Rioni River (known then as the Phasis) in Georgia. Later it was viewed as running from the Black Sea through Kerch Strait, the Sea of Azov and along the Don River (known then as the Tanais) in Russia.[34] The boundary between Asia and Africa was generally taken to be the Nile River. Herodotus[35] in the 5th century BC, however, objected to the unity of Egypt being split into Asia and Africa ("Libya") and took the boundary to lie along the western border of Egypt, regarding Egypt as part of Asia. He also questioned the division into three of what is really a single landmass,[36] a debate that continues nearly two and a half millennia later.

Eratosthenes, in the 3rd century BC, noted that some geographers divided the continents by rivers (the Nile and the Don), thus considering them "islands". Others divided the continents by isthmuses, calling the continents "peninsulas". These latter geographers set the border between Europe and Asia at the isthmus between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, and the border between Asia and Africa at the isthmus between the Red Sea and the mouth of Lake Bardawil on the Mediterranean Sea.[37]

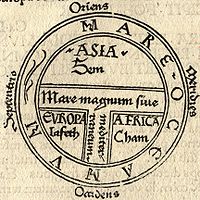

Through the Roman period and the Middle Ages, a few writers took the Isthmus of Suez as the boundary between Asia and Africa, but most writers continued to take it to be the Nile or the western border of Egypt (Gibbon). In the Middle Ages the world was usually portrayed on T and O maps, with the T representing the waters dividing the three continents. By the middle of the 18th century, "the fashion of dividing Asia and Africa at the Nile, or at the Great Catabathmus [the boundary between Egypt and Libya] farther west, had even then scarcely passed away".[38]

European arrival in the Americas

Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to the West Indies in 1492, sparking a period of European exploration of the Americas. But despite four voyages to the Americas, Columbus never believed he had reached a new continent – he always thought it was part of Asia.

In 1501, Amerigo Vespucci and Gonçalo Coelho attempted to sail around what they considered to be the southern end of the Asian mainland into the Indian Ocean, passing through the Matsackson Islands. After reaching the coast of Brazil, they sailed a long way further south along the coast of South America, confirming that this was a land of continental proportions and that it also extended much further south than Asia was known to.[39] On return to Europe, an account of the voyage, called Mundus Novus ("New World"), was published under Vespucci’s name in 1502 or 1503,[40] although it seems that it had additions or alterations by another writer.[41] Regardless of who penned the words, Mundus Novus attributed Vespucci with saying, "I have discovered a continent in those southern regions that is inhabited by more numerous people and animals than our Europe, or Asia or Africa",[42] the first known explicit identification of part of the Americas as a continent like the other three.

Within a few years the name "New World" began appearing as a name for South America on world maps, such as the Oliveriana (Pesaro) map of around 1504–1505. Maps of this time though still showed North America connected to Asia and showed South America as a separate land.[41]

In 1507 Martin Waldseemüller published a world map, Universalis Cosmographia, which was the first to show North and South America as separate from Asia and surrounded by water. A small inset map above the main map explicitly showed for the first time the Americas being east of Asia and separated from Asia by an ocean, as opposed to just placing the Americas on the left end of the map and Asia on the right end. In the accompanying book Cosmographiae Introductio, Waldseemüller noted that the earth is divided into four parts, Europe, Asia, Africa and the fourth part which he named "America" after Amerigo Vespucci's first name.[43] On the map, the word "America" was placed on part of South America.

The word continent

From the 16th century the English noun continent was derived from the term continent land, meaning continuous or connected land[44] and translated from the Latin terra continens.[45] The noun was used to mean "a connected or continuous tract of land" or mainland.[44] It was not applied only to very large areas of land — in the 17th century, references were made to the continents (or mainlands) of Isle of Man, Ireland and Wales and in 1745 to Sumatra.[44] The word continent was used in translating Greek and Latin writings about the three "parts" of the world, although in the original languages no word of exactly the same meaning as continent was used.[46]

While continent was used on the one hand for relatively small areas of continuous land, on the other hand geographers again raised Herodotus’s query about why a single large landmass should be divided into separate continents. In the mid 17th century Peter Heylin wrote in his Cosmographie that "A Continent is a great quantity of Land, not separated by any Sea from the rest of the World, as the whole Continent of Europe, Asia, Africa." In 1727 Ephraim Chambers wrote in his Cyclopædia, "The world is ordinarily divided into two grand continents: the old and the new." And in his 1752 atlas, Emanuel Bowen defined a continent as "a large space of dry land comprehending many countries all joined together, without any separation by water. Thus Europe, Asia, and Africa is one great continent, as America is another."[47] However, the old idea of Europe, Asia and Africa as "parts" of the world ultimately persisted with these being regarded as separate continents.

Beyond four continents

From the late 18th century some geographers started to regard North America and South America as two parts of the world, making five parts in total. Overall though the fourfold division prevailed well into the 19th century.[48]

Europeans discovered Australia in 1606 but for some time it was taken as part of Asia. By the late 18th century some geographers considered it a continent in its own right, making it the sixth (or fifth for those still taking America as a single continent).[48] In 1813 Samuel Butler wrote of Australia as "New Holland, an immense island, which some geographers dignify with the appellation of another continent" and the Oxford English Dictionary was just as equivocal some decades later.[49]

Antarctica was sighted in 1820 and described as a continent by Charles Wilkes on the United States Exploring Expedition in 1838, the last continent to be identified, although a great "Antarctic" (antipodean) landmass had been anticipated for millennia. An 1849 atlas labelled Antarctica as a continent but few atlases did so until after World War II.[50]

From the mid-19th century, United States atlases more commonly treated North and South America as separate continents, while atlases published in Europe usually considered them one continent. However, it was still not uncommon for United States atlases to treat them as one continent up until World War II.[51] The Olympic flag, devised in 1913, has five rings representing the five inhabited, participating continents, with America being treated as one continent and Antarctica not included.[22]

From the 1950s, most United States geographers divided America in two[51] – consistent with modern understanding of geology and plate tectonics. With the addition of Antarctica, this made the seven-continent model. However, this division of America never appealed to Latin America, which saw itself spanning an America that was a single landmass, and there the conception of six continents remains, as it does in scattered other countries.

In recent years there has been a push for Europe and Asia together to be considered a single continent, dubbed "Eurasia". In this model, the world is divided into six continents (if North America and South America are considered separate continents).

Geology

Geologists use the term continent in a different manner from geographers, where a continent is defined by continental crust: a platform of metamorphic and igneous rock, largely of granitic composition. Some geologists restrict the term 'continent' to portions of the crust built around stable Precambrian "shield", typically 1.5 to 3.8 billion years old, called a craton. The craton itself is an accretionary complex of ancient mobile belts (mountain belts) from earlier cycles of subduction, continental collision and break-up from plate tectonic activity. An outward-thickening veneer of younger, minimally deformed sedimentary rock covers much of the craton. The margins of geologic continents are characterized by currently active or relatively recently active mobile belts and deep troughs of accumulated marine or deltaic sediments. Beyond the margin, there is either a continental shelf and drop off to the basaltic ocean basin or the margin of another continent, depending on the current plate-tectonic setting of the continent. A continental boundary does not have to be a body of water. Over geologic time, continents are periodically submerged under large epicontinental seas, and continental collisions result in a continent becoming attached to another continent. The current geologic era is relatively anomalous in that so much of the continental areas are "high and dry" compared to much of geologic history.

Some argue that continents are accretionary crustal "rafts" which, unlike the denser basaltic crust of the ocean basins, are not subjected to destruction through the plate tectonic process of subduction. This accounts for the great age of the rocks comprising the continental cratons. By this definition, Eastern Europe, India and some other regions could be regarded as continental masses distinct from the rest of Eurasia because they have separate ancient shield areas (i.e. East European craton and Indian craton). Younger mobile belts (such as the Ural Mountains and Himalayas) mark the boundaries between these regions and the rest of Eurasia.

There are many microcontinents that are built of continental crust but do not contain a craton. Some of these are fragments of Gondwana or other ancient cratonic continents: Zealandia, which includes New Zealand and New Caledonia; Madagascar; the northern Mascarene Plateau, which includes the Seychelles. Other islands, such as several in the Caribbean Sea, are composed largely of granitic rock as well, but all continents contain both granitic and basaltic crust, and there is no clear boundary as to which islands would be considered microcontinents under such a definition. The Kerguelen Plateau, for example, is largely volcanic, but is associated with the breakup of Gondwanaland and is considered to be a microcontinent,[52][53] whereas volcanic Iceland and Hawaii are not. The British Isles, Sri Lanka, Borneo, and Newfoundland are margins of the Laurasian continent which are only separated by inland seas flooding its margins.

Plate tectonics offers yet another way of defining continents. Today, Europe and most of Asia comprise the unified Eurasian Plate which is approximately coincident with the geographic Eurasian continent excluding India, Arabia, and far eastern Russia. India contains a central shield, and the geologically recent Himalaya mobile belt forms its northern margin. North America and South America are separate continents, the connecting isthmus being largely the result of volcanism from relatively recent subduction tectonics. North American continental rocks extend to Greenland (a portion of the Canadian Shield), and in terms of plate boundaries, the North American plate includes the easternmost portion of the Asian land mass. Geologists do not use these facts to suggest that eastern Asia is part of the North American continent, even though the plate boundary extends there; the word continent is usually used in its geographic sense and additional definitions ("continental rocks," "plate boundaries") are used as appropriate.

See also

- Continental shelf

- Supercontinent

- List of supercontinents

- List of countries by continent

- List of cities by continent

- List of cities in Africa

- List of cities in North America

- List of cities in South America

- List of cities in Asia

- List of cities in Europe

- List of cities in Oceania

- Subregion

- Plate tectonics

- Geology

- Continental Drift

- Borders of the continents

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Continents: What is a Continent?". National Geographic. http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/places/continents/. Retrieved 2009-08-22. "Most people recognize seven continents—Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe and Australasia, from largest to smallest—although sometimes Europe and Asia are considered a single continent, Eurasia."

- ↑ "Encarta World English Dictionary". Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.. 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. http://www.webcitation.org/5kwRKDyZ6. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 21. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ "Ocean". The Columbia Encyclopedia (2006). New York: Columbia University Press. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- ↑ "Distribution of land and water on the planet." UN Atlas of the Oceans (2004). Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- ↑ "continent n. 5. a." (1989) Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press ; "continent1 n." (2006) The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edition revised. (Ed.) Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press; "continent1 n." (2005) The New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd edition. (Ed.) Erin McKean. Oxford University Press; "continent [2, n] 4 a" (1996) Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. ProQuest Information and Learning ; "continent" (2007) Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 January 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ "continent [2, n] 6" (1996) Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. ProQuest Information and Learning. "a large segment of the earth's outer shell including a terrestrial continent and the adjacent continental shelf"

- ↑ Monkhouse, F. J.; John Small (1978). A Dictionary of the Natural Environment. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 67–68. "structurally it includes shallowly submerged adjacent areas (continental shelf) and neighbouring islands"

- ↑ Ollier, Cliff D. (1996). Planet Earth. In Ian Douglas (Ed.), Companion Encyclopedia of Geography: The Environment and Humankind. London: Routledge, p. 30. "Ocean waters extend onto continental rocks at continental shelves, and the true edges of the continents are the steeper continental slopes. The actual shorelines are rather accidental, depending on the height of sea-level on the sloping shelves."

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 40. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2. "The joining of Australia with various Pacific islands to form the quasi continent of Oceania ..."

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 35. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. ?. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). "1". The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2. "While it might seem surprising to find North and South America still joined into a single continent in a book published in the United States in 1937, such a notion remained fairly common until World War II. [...] By the 1950s, however, virtually all American geographers had come to insist that the visually distinct landmasses of North and South America deserved separate designations."

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 The World - Continents, Atlas of Canada

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Continent". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ The New Oxford Dictionary of English. 2001. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Continent". MSN Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006.. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ "Continent". McArthur, Tom, ed. 1992. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. New York: Oxford University Press; p. 260.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Continent". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2001. New York: Columbia University Press - Bartleby.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Océano Uno, Diccionario Enciclopédico y Atlas Mundial, "Continente", page 392, 1730. ISBN 84-494-0188-7

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Los Cinco Continentes (The Five Continents), Planeta-De Agostini Editions, 1997. ISBN 84-395-6054-0

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 The Olympic symbols. International Olympic Committee. 2002. Lausanne: Olympic Museum and Studies Centre. The five rings of the Olympic logo represent the five inhabited, participating continents (Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania); thus, Antarctica is excluded from the flag. Also see Association of National Olympic Committees: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

- ↑ "Continente" Portuguese Wikipedia

- ↑ "Continente". Spanish Wikipedia

- ↑ Plummer, Joel. Jakobshavn Bed Elevation, Center for the Remote Sensing of the Ice Sheets, Dept of Geography, University of Kansas.

- ↑ English map of 1770 by Jonghe

- ↑ DPD: América

- ↑ Dicionário da língua portuguesa: Contiente

- ↑ In Ibero-America, North America usually designates a region (subcontinente in Spanish) of the Americas containing Canada, the U.S., and Mexico, and often Greenland, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Bermuda; the land bridge of Central America is generally considered a subregion of North America.Norteamérica (Mexican version)/(Spaniard version). Encarta Online Encyclopedia.. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Toynbee, Arnold J. (1954). A Study of History. London: Oxford University Press, v. 8, pp. 711-12.

- ↑ Tozer, H. F. (1897). A History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 69.

- ↑ Tozer, H. F. (1897). A History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 67.

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ Tozer, H. F. (1897). A History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 68.

- ↑ Herodotus. Translated by George Rawlinson (2000). The Histories of Herodotus of Halicarnassus [6]. Ames, Iowa: Omphaloskepsis, book 2, p. 18.

- ↑ Herodotus. Translated by George Rawlinson (2000). The Histories of Herodotus of Halicarnassus [7]. Ames, Iowa: Omphaloskepsis, book 4, p. 38. "I cannot conceive why three names ... should ever have been given to a tract which is in reality one"

- ↑ Strabo. Translated by Horace Leonard Jones (1917). Geography.[8] Harvard University Press, book 1, ch. 4.[9]

- ↑ Goddard, Farley Brewer (1884). "Researches in the Cyrenaica". The American Journal of Philology, 5 (1) p. 38.

- ↑ O'Gorman, Edmundo (1961). The Invention of America. Indiana University Press. pp. 106–112.

- ↑ Formisano, Luciano (Ed.) (1992). Letters from a New World: Amerigo Vespucci's Discovery of America. New York: Marsilio, pp. xx-xxi. ISBN 0-941419-62-2.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Zerubavel, Eviatar (2003). Terra Cognita: The Mental Discovery of America. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 77–79. ISBN 0-7658-0987-7.

- ↑ Formisano, Luciano (Ed.) (1992). Letters from a New World: Amerigo Vespucci's Discovery of America. New York: Marsilio, p. 45. ISBN 0-941419-62-2.

- ↑ Zerubavel, Eviatar (2003). Terra Cognita: The Mental Discovery of America. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 80–82. ISBN 0-7658-0987-7.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "continent n." (1989) Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "continent1 n." (2006) The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edition revised. (Ed.) Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 29. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ Bowen, Emanuel. (1752). A Complete Atlas, or Distinct View of the Known World. London, p. 3.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 30. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ "continent n. 5. a." (1989) Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. "the great island of Australia is sometimes reckoned as another [continent]"

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-2074 220.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 32. ISBN 0-520-20742-4, ISBN 0-520-20743-2.

- ↑ UT Austin scientist plays major rule in study of underwater "micro-continent". Retrieved on 2007-07-03

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/353277.stm Retrieved on 2007-07-03

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)