Comic book

A comic book (often shortened to simply comic and sometimes called a funny book, comic paper or comic magazine) is a magazine made up of narrative artwork in the form of separate "panels" that represent individual scenes, often accompanied by dialog (usually in word balloons, emblematic of the comic book art form) as well as including brief descriptive prose. The first comic book appeared in the United States of America in 1934, reprinting the earlier newspaper comic strips, which established many of the story-telling devices used in comics. The term "comic book" arose because the first comic books reprinted humor comic strips, but despite their name, comic books do not necessarily operate in humorous mode; most modern comic books tell stories in a variety of genres. The Japanese and European comic book markets demonstrate this clearly. In the United States the super-hero genre dominates the market, even though other genres also exist.

Contents |

American comics

Since the introduction of the comic-book format in 1934 with the publication of Famous Funnies, the United States has produced the most titles, with only the British comic and Japanese manga as close competitors in terms of quantity of titles. The comic-book industry in the U.S. markets the majority of its output to young adult readers, though it also produces titles for young children as well as catering to adult audiences.

Cultural historians divide the career of the comic book in the U.S. into several ages or historical eras:

- the Proto-comic books and the Platinum Age

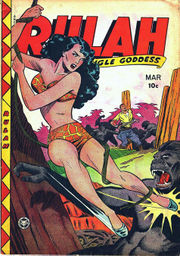

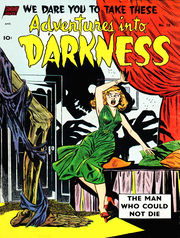

- the Golden Age

- the Silver Age

- the Bronze Age

- the Modern Age

Comic-book historians continue to debate the exact boundaries of these eras, the terms for which originated in the fandom press.

Comic books as a print medium have existed in America since the printing of The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck in 1842 in hard cover - making it not only the first known American comic book but the first American graphic novel as well. The introduction of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's Superman in 1938 turned comic books into a major industry,[1] and is often presented as the start of the Golden Age of comics. Historians have proposed several names for the Age before Superman, most commonly dubbing it the Platinum Age.[2]

While the Platinum Age saw the first use of the term "comic book" (The Yellow Kid in McFadden's Flats (1897)), the first known full-color comic (The Blackberries (1901)), and the first monthly comic book (Comics Monthly (1922)) it was not until the Golden Age that the archetype of the superhero would originate.

The Silver Age of Comic Books is generally considered to date from the first successful revival of the dormant superhero form — the debut of Robert Kanigher and Carmine Infantino's Flash in Showcase #4 (September-October 1956).[3][4] The Silver Age lasted through the early 1970s, during which time Marvel Comics revolutionized the medium with such naturalistic superheroes as Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's Fantastic Four and Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's Spider-Man.

The precise beginnings of the Bronze and Modern ages remain less well-defined. Suggested starting points for the Bronze Age of comics include Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith's Conan #1 (October 1970), Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams' Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76 (April 1970) or Stan Lee and Gil Kane's Amazing Spider-Man #96 (May 1971) (the non-Comics Code issue). The start of the Modern Age (occasionally referred to as the "Iron Age") has even more potential starting points, but is generally agreed to be the publication of Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns graphic novel and Alan Moore's Watchmen by DC Comics in 1986, as well as the publication of DC's Crisis on Infinite Earths, with Marv Wolfman as writer and George Pérez on the pencils.

Comics published after World War II in 1945 sometimes get labelled as products of the "Atomic Age" (referring to the dropping of the atomic bomb), while commentators sometimes refer to titles published after November 1961 as belonging to the "Marvel Age" (referring to the advent of Marvel Comics). However, the secondary literature refers to these "eras" far less frequently than to the aforementioned designations.

A notable event in the history of the American comic book came with the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham's criticisms of the medium in his book Seduction of the Innocent (1954), which prompted the American Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency to investigate comic books. In response to attention from the government and from the media, the US comic book industry set up the Comics Code Authority in 1954 and drafted the Comics Code in the same year.

Underground comics

In the late 1960s and early 1970s a surge of creativity emerged in what became known as underground comics. Published and distributed independently of the established comics industry, most of such comics reflected the youth counterculture and drug culture of the time. Many had an uninhibited, often irreverent style; their frank depictions of nudity, sex, profanity, and politics had no parallel outside their precursors, the pornographic and even more obscure "Tijuana bibles". Underground comics were almost never sold at news stands, but rather in such youth-oriented outlets as head shops and record stores, as well as by mail order.

Frank Stack's The Adventures of Jesus, published under the name Foolbert Sturgeon,[5][6] has been credited as the first underground comic.[5][6]

Alternative comics

The rise of comic-book specialty stores in the late 1970s created/paralleled a dedicated market for "independent" or "alternative comics" in the United States. The first such comics included the anthology series Star Reach, published by comic-book writer Mike Friedrich from 1974 to 1979, and Harvey Pekar's American Splendor, which continued sporadic publication into the 21st century and which Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini adapted into a 2003 film. Some independent comics continued in the tradition of underground comics, though their content was generally less explicit, and others resembled the output of mainstream publishers in format and genre but were published by smaller artist-owned companies or by single artists. A few (notably RAW) were experimental attempts to bring comics closer to the status of fine art.

During the 1970s the "small press" culture grew and diversified. By the 1980s several independent publishers, such as Pacific, Eclipse, First, Comico and Fantagraphics had started releasing a wide range of styles and formats: from color superhero, detective and science fiction comic books to black-and-white magazine-format stories of Latin American magical realism.

A number of small publishers in the 1990s changed the format and distribution of their comics to more closely resemble non-comics publishing. The "minicomics" form, an extremely informal version of self-publishing, arose in the 1980s and became increasingly popular among artists in the 1990s, despite reaching an even more limited audience than the small press.

As of 2009[update] small publishers regularly releasing titles include Avatar Comics, Hyperwerks, Raytoons, and Terminal Press, buoyed by such advances in printing technology as digital print-on-demand.

Graphic novels

Rich Kyle coined the term "graphic novel" in 1964 in an attempt to distinguish newly translated European works from what Kyle perceived as the more juvenile subject matter common in the United States.

Will Eisner popularized the term when he used it on the cover of the paperback edition of his work A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories in 1978. This represented a more thematically mature work than many had come to expect from the comics medium, and the critical success of A Contract with God helped to bring the term into common usage.

Rarest American comic books

The rarest comic books include copies of the unreleased Motion Picture Funnies Weekly #1 from 1939. Eight copies, plus one without a cover, emerged in the estate of the deceased publisher in 1974.

Before Fawcett Comics introduced Captain Marvel Misprints, promotional comic-dealer incentive printings, and similar issues with extremely low distribution also generally have scarcity value. The rarest modern comic books include the original press run of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen #5, which DC executive Paul Levitz ordered recalled and pulped due to the appearance of a vintage Victorian era advertisement for "Marvel Douche", which the publisher considered offensive[7]; only 100 copies are thought to exist, most of which have been CGC graded. (See Recalled comics for more pulped, recalled and erroneous comics).

In modern times, a new array of original comics have emerged with surprising high value. An example would be one of the three remaining original first episodes of the TS Comics series "Tyler Man", by "Tyler Ebert". Although the majority of these comics are read only by teenagers, a copy recently sold by the author brought forth enough money to, in his words, "Pay for a semester of college."

European comics

Franco-Belgian Comics

France and Belgium have a long tradition in comics and comic books, called BDs (an abbreviation of bande dessinées) in French and strips in Dutch. Belgian comic books originally written in Dutch show the influence of the Francophone "Franco-Belgian" comics, but have their own distinct style.

The name la bande dessinée derives from the original description of the art form as drawn strips (the phrase literally translates as "the drawn strip"), analogous to the sequence of images in a film strip. As in its English equivalent, the word "bande" can be applied to both film and comics. Significantly, the French-language term contains no indication of subject-matter, unlike the American terms "comics" and "funnies", which imply an art form not to be taken seriously. The distinction of comics as le neuvième art (literally, "the ninth art") is prevalent in French scholarship on the form, as is the concept of comics criticism and scholarship itself. Relative to the respective size of their populations, the innumerable authors in France and Belgium publish a high volume of comic books. In North America, the more serious Franco-Belgian comics are often seen as equivalent to graphic novels, but whether they are long or short, bound or in magazine format, in Europe there is no need for a more sophisticated term, as the art's name does not itself imply something frivolous.

In France, authors control the publication of most comics. The author works within a self-appointed time-frame, and it is common for readers to wait six months or as long as two years between installments. Most books first appear in print as a hard cover book, typically with 48, 56 or 64 pages.

British comics

Originally the same size as a usual comic book in the United States (although lacking the glossy cover) the British comic has adopted a magazine size, with The Beano and The Dandy the last to adopt this size (in the 1980s). Although the British generally speak of "a comic" or of "a comic magazine", and they also historically spoke of "a comic paper". Some comics, such as Judge Dredd and other 2000 AD titles, have been published in a tabloid form.

Although Ally Sloper's Half Holiday (1884), the first comic published in Britain, aimed at an adult market, publishers quickly targeted a younger market, which has led to most publications being for children and created an association in the public's mind of comics as somewhat juvenile.

Popular titles within the UK have included The Beano, The Dandy, The Eagle, 2000 AD and Viz. Underground comics and "small press" titles have also been published within the United Kingdom, notably Oz and Escape Magazine.

The content of Action, another title aimed at children and launched in the mid 1970s, became the subject of discussion in the House of Commons. Although on a smaller scale than similar investigations in the United States, such concerns led to a moderation of content published within British comics. Such moderation never became formalized to the extent of promulgating a code, nor did it last long.

The UK has also established a healthy market in the reprinting and repackaging of material, notably material originating in the United States. The lack of reliable supplies of American comic books led to a variety of black-and-white reprints, including Marvel's monster comics of the 1950s, Fawcett's Captain Marvel, and other characters such as Sheena, Mandrake the Magician, and the Phantom. Several reprint companies were involved in repackaging American material for the British market, notably the importer and distributor Thorpe & Porter.

Marvel Comics established a UK office in 1972. DC Comics and Dark Horse Comics also opened offices in the 1990s. The repackaging of European material has occurred less frequently, although the Tintin and Asterix serials have been successfully translated and repackaged in soft cover books.

At Christmas time, publishers repackage and commission material for comic annuals, printed and bound as hardcover A4-size books: Rupert supplies a famous example of the British comic annual. DC Thomson also repackage The Broons and Oor Wullie strips in softcover A4-size books for the holiday season.

Italian comics

In Italy, comics (known in Italian as fumetti) made their debut as humor strips at the end of the nineteenth century, and later evolved into adventure stories inspired by those coming from the US. After World War II, however, artists like Hugo Pratt and Guido Crepax exposed Italian comics to an international audience. "Author" comics contain often strong erotic contents. Popular comic books such as Diabolik or the Bonelli line - namely Tex Willer or Dylan Dog - remain best-sellers.

Mainstream comics are usually published on a monthly basis, in a black-and-white digest size format, with approximately 100 to 132 pages. Collections of classic material for the most famous characters, usually with more than 200 pages, are also common. Author comics are published in the French BD format, with an example being Pratt's Corto Maltese.

Italian cartoonists show the influence of comics from other countries, including France, Belgium, Spain, and Argentina. Italy is also famous for being one of the foremost producers of Walt Disney comic stories outside the US. Donald Duck's superhero alter ego, Paperinik, known in English as Superduck, was created in Italy.

Other European comics

Although Switzerland has made relatively few contributions to European comics, many scholars point to a Francophone Swiss, Rodolphe Töpffer, as the true father of comics. However, this assertion remains controversial, with critics noting that Töpffer's work does not necessarily connect to the creation of the artform as it is now known in the region.

Japanese comics

The first comic books in Japan appeared during the 18th century in the form of woodblock- printed booklets containing short stories drawn from folk tales, legends, and historical accounts, told in a simple visual-verbal idiom. Known as "red books" (赤本 akahon), "black books" (黒本 kurobon), and "blue books" (青本 aohon), these were written primarily for less literate readers. However, with the publication in 1775 of Koikawa Harumachi's comic book Master Flashgold's Splendiferous Dream (金々先生栄花の夢 Kinkin sensei eiga no yume), an adult form of comic book originated, which required greater literacy and cultural sophistication. This was known as the kibyōshi (黄表紙?, lit. yellow cover). Published in thousands (possibly tens of thousands) of copies, the kibyōshi may have been the earliest fully realized comic book for adults in world literary history. Approximately 2000 titles remain extant.

Modern comic books in Japan developed from a mixture of these earlier comic books and of woodblock prints ukiyo-e (浮世絵) with Western styles of drawing. They took their current[update] form shortly after World War II. They are usually published in black and white, except for the covers, which are usually printed in four colors, although occasionally, the first few pages may also be printed in full color. The term manga means "random (or whimsical) pictures", and first came into common usage in the late eighteenth century with the publication of such works as Santō Kyōden's picturebook Shiji no yukikai (四時交加) (1798) and Aikawa Minwa's Comic Sketches of a Hundred Women (1798).

Development of this form occurred as a result of Japan's attempts to modernize itself, a desire awakened by trade with the United States. Western artists were brought over to teach their students such concepts as line, form, and color, things which had not been regarded as conceptually important in ukiyo-e, as the idea behind the picture was of paramount importance. Manga at this time was referred to as Ponchi-e (Punch-picture) and, like its British counterpart Punch magazine, mainly depicted humour and political satire in short one- or four-picture format.

Dr. Osamu Tezuka (1928–1989), widely acknowledged as the father of narrative manga, further developed this form. Seeing an animated war propaganda film titled Momotaro's Divine Sea Warriors (桃太郎 海の神兵 Momotarō Umi no Shinpei) inspired Tezuka to become a comic artist. He introduced episodic storytelling and character development in comic format, in which each story is part of larger story arc. The only text in Tezuka's comics was the characters' dialogue and this further lent his comics a cinematic quality. Inspired by the work of Walt Disney, Tezuka also adopted a style of drawing facial features in which a character's eyes, nose, and mouth are drawn in an extremely exaggerated manner. This style created immediately recognizable expressions using very few lines, and the simplicity of this style allowed Tezuka to be prolific. Tezuka’s work generated new interest in the ukiyo-e tradition, in which the image is a representation of an idea, rather than a depiction of reality.

Though a close equivalent to the American comic book, manga has historically held a more important place in Japanese culture than comics have in American culture. Japanese society shows a wide respect for manga: both as an art form and as a form of popular literature. Many manga become TV shows or shorter movies. As with its American counterpart, some manga has been criticized for its sexuality and violence, although in the absence of official or even industry restrictions on content, artists have freely created manga for every age group and for every topic.

Manga magazines — also known as "anthologies", or colloquially, "phone books" — often run several series concurrently, with approximately 20 to 40 pages allocated to each series per issue. These magazines are usually printed on low-quality newsprint and range from 200 to more than 850 pages each. Manga magazines also contain one-shot comics and a variety of four-panel yonkoma (equivalent to comic strips). Manga series may continue for many years if they are successful, with stories often collected and reprinted in book-sized volumes called tankōbon (単行本?, lit. stand-alone book), the equivalent of the American trade paperbacks. These volumes use higher-quality paper and are useful to readers who want to be brought up to date with a series, or to readers who find the cost of the weekly or monthly publications to be prohibitive. Deluxe versions are printed, as commemorative or collectible editions. Conversely, old manga titles are also reprinted using lower-quality paper and sold for 120 ¥ (approximately $1 USD) each.

Genres of manga

Manga titles are primarily classified according to the demographics of their intended audience. The most popular forms of manga target the markets of young boys (shōnen manga) and young girls (shōjo manga). Other categories include adult comics (seinen manga) and "businessman" comics. Each of these types occupy their own shelves in most Japanese bookstores. Comics with adult content (ero manga) usually sell in doujinshi stores rather than normal bookstores.

Doujinshi

Doujinshi (同人誌?, lit. fan magazine), fan-made Japanese comics operate in a far larger market in Japan than the American "underground comics" market; the largest doujinshi fair, Comic Market, attracts 500,000 visitors twice a year.

Other comics

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Goulart, Ron. Comic Book Culture: An Illustrated History (Collectors Press), p. 43. ISBN-10 1888054387, ISBN-13 978-1888054385

- ↑ "History of Comic Books Victorian and Platinum Ages" (Internet Archive)

- ↑ CBR News Team (July 2, 2007). "DC Flashback: The Flash". Comic Book Resources. http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=10649. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ Zicari, Anthony (August 3, 2007). "Breaking the Border - Rants and Ramblings". Comics Bulletin (Internet archive version). http://web.archive.org/web/20070826092448/http://www.silverbulletcomics.com/news/story.php?a=5706. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Shelton, Gilbert (2006). "Introduction". The New Adventures of Jesus. Fantagraphics Books. p. 9. ISBN 9781560977803.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Skinn, Dez (2004). "Heroes of the Revolution". Comix: The Underground Revolution. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 34. ISBN 1560255722.

- ↑ Comic Book Resources (May 23, 2005): Living in the Gutters (column by Rich Johnston): sidebar "Alan's Previous Problems With DC" in column "Moore Slams V for Vendetta Movie, Pulls LoEG from DC Comics"

References

- Kern, Adam L., Manga from the Floating World: Comic book Culture and the Kibyôshi of Edo Japan (Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2006) ISBN 0-674-02266-1.

- Inge, Thomas M., "Comics as culture". Journal of Popular Culture 12:631, 1979

External links

- The Comic Book Database

- Coville, Jamie. The History of Comic Books: Introduction and "The Platinum Age 1897 - 1938", TheComicBooks.com, n.d. Originally published at defunct site CollectorTimes.com.

- Grand Comics Database

- Comic book Reference Bibliographic Datafile

- How Comic Books Became Part of the Literary Establishment by Tim Martin, Telegraph, April 2, 2009

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||