Classics

Classics (also known as Classical Studies or Classical Civilisation) is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world (Bronze Age ca. BC 3000 – Late Antiquity ca. AD 300–600); especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity (ca. BC 600 – AD 600). Initially, study of the Classics (the period's literature) was the principal study in the humanities.

Contents |

History of the Western Classics

The word “classics” derives from the Latin adjective classicus: “belonging to the highest class of citizens”, connoting superiority, authority, and perfection. The first application of “Classic” to a writer was by Aulus Gellius, a second-century Roman writer who, in the miscellany Noctes Atticae (19, 8, 15), refers to a writer as a Classicus scriptor, non proletarius (“A distinguished, not a commonplace writer”). Such classification began with the Greeks’ ranking their cultural works, with the word canon (“carpenter’s rule”). Moreover, early Christian Church Fathers used canon to rank the authoritative texts of the New Testament, preserving them, given the expense of vellum and papyrus and mechanical book reproduction, thus, being comprehended in a canon ensured a book’s preservation as the best of a civilisation. Contemporarily, the Western canon defines the best of Western culture. In the ancient world, at the Alexandrian Library, scholars coined the Greek term Hoi enkrithentes (“the admitted”, “the included”) to identify the writers in the canon.

The method of study in the Classical World was “Philo’s Rule”: μεταχάραττε τὸ θεῖον νόμισμα (lit.: "strike the divine coin anew")—the law of strict continuity in preserving words and ideas.[1] Although the definitions of words and ideas might broaden, continuity (preservation) requires retention of their original arete (excellence, virtue, goodness). “Philo’s Rule” imparts intellectual and æsthetic appreciation of “the best which has been thought and said in the world”. To wit, Oxford classicist Edward Copleston said that classical education “communicates to the mind…a high sense of honour, a disdain of death in a good cause, [and] a passionate devotion to the welfare of one’s country”,[2] thus concurring with Cicero that: “All literature, all philosophical treatises, all the voices of antiquity are full of examples for imitation, which would all lie unseen in darkness without the light of literature”.

Legacy of the Classical World

The Classical languages of the Ancient Mediterranean world influenced every European language, imparting to each a learned vocabulary of international application. Thus, Latin grew from a highly developed cultural product of the Golden and Silver eras of Latin literature to become the international lingua franca in matters diplomatic, scientific, philosophic and religious, until the seventeenth century. In turn, the Classical languages continued, Latin evolved into the Romance languages and Ancient Greek into Modern Greek and its dialects. Moreover, it is in the specialised science and technology vocabularies that the Latin influence in English and the Greek influence in English are notable, however, it is Ecclesiastical Latin, the Roman Catholic Church’s official tongue, that remains a living legacy of the classical world to the contemporary world.

Sub-disciplines within the classics

One of the most notable characteristics of the modern study of classics is the diversity of the field. Although traditionally focused on ancient Greece and Rome, the study now encompasses the entire ancient Mediterranean world, thus expanding their studies to Northern Africa and parts of the Middle East.

Philology

Traditionally, classics was essentially the philology of ancient texts. Although now less dominant, philology retains a central role. One definition of classical philology describes it as "the science which concerns itself with everything that has been transmitted from antiquity in the Greek or Latin language. The object of this science is thus the Graeco-Roman, or Classical, world to the extent that it has left behind monuments in a linguistic form."[3] Of course, classicists also concern themselves with other languages than Classical Greek and Latin including Linear A, Linear B, Sanskrit, Hebrew, Oscan, Etruscan, and many more. Before the invention of the printing press, texts were reproduced by hand and distributed haphazardly. As a result, extant versions of the same text often differ from one another. Some classical philologists, known as textual critics, seek to synthesize these defective texts to find the most accurate version.

Archaeology

Classical archæology is the investigation of the physical remains of the great Mediterranean civilizations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The archæologists’ field, laboratory, library, and documentation work make available the extant literary and linguistic cultural artefacts to the field’s sub-disciplines, such as Philology. Like-wise, archæologists rely upon the philology of ancient literatures in establishing historic contexts among the classic-era remains of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

Art history

Some art historians focus their study of the development of art on the classical world. Indeed, the art and architecture of Ancient Rome and Greece is very well regarded and remains at the heart of much of our art today. For example, Ancient Greek architecture gave us the Classical Orders: Doric order, Ionic order, and Corinthian order. The Parthenon is still the architectural symbol of the classical world.

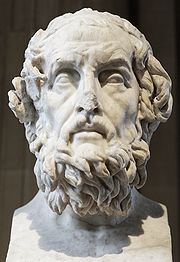

Greek sculpture is well known and we know the names of several Ancient Greek artists: for example, Phidias.

Civilization and history

With philology, archæology, and art history, scholars seek understanding of the history and culture of a civilisation, through critical study of the extant literary and physical artefacts, in order to compose and establish a continual historic narrative of the Ancient World and its peoples. The task is difficult, given the dearth of physical evidence; for example, Sparta was a leading Greek city-state, yet little evidence of it survives to study, and what is available comes from Athens, Sparta’s principal rival; like-wise, the Roman Empire destroyed most evidence (cultural artefacts) of earlier, conquered civilizations, such as that of the Etruscans.

Philosophy

Pythagoras coined the word philosophy (“love of wisdom”), the work of the “Philosopher” who seeks understanding of the world as it is, thus, most classics scholars recognize that the roots of Western philosophy originate in Greek philosophy, the works of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics.

Classical Greece

| Greek Philosophy | Greek Mythology and religion | Greek Science | Greek History | Greek Literature | Greek Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Classical Rome

| Roman Philosophy | Roman mythology and religion | Roman Science | Roman History | Roman Literature | Latin Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Astrology/Astronomy

|

|

|

Famous Classicists

Throughout the history of the Western world, many classicists have gone on to gain acknowledgment outside the field.

- George Berkeley, philosopher, read Classics at Trinity College, Dublin, where he was also Junior Lecturer in Greek

- John Buchan, writer and politician, who served as Governor General of Canada.

- Sir James George Frazer, poet and anthropologist

- William Ewart Gladstone, 19th century British Prime Minister, studied classics at Oxford University

- A.E. Housman, best known to the public as a poet and the author of A Shropshire Lad, was the most accomplished (and feared) textual critic of his generation and held the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge from 1911 until his death in 1936.

- Karl Marx, philosopher and political thinker, studied Latin and Greek and received a Ph.D. for a dissertation on ancient Greek philosophy, entitled "The Difference between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature." His classical background is reflected in his philosophies—indeed the term "proletariat" which he coined came from that Latin word referring to the lowest class of citizen.

- John Milton, author of Paradise Lost and English Civil War figure; studied, like many educated people of the time, Latin and Greek texts, which influenced Paradise Lost

- Theodor Mommsen, author of History of Rome and works on Roman law; German politician, delegate in the Reichstag during the German Empire period

- Friedrich Nietzsche, philosopher; earned Ph.D. and became Professor of Classics at the University of Basel in Switzerland

- Enoch Powell, British Conservative and later Ulster Unionist politician; wrote and edited texts on Herodotus

- P.G. Wodehouse, writer, playwright, lyricist and creator of Jeeves; studied classics at Dulwich College

- Oscar Wilde, 19th-century playwright and poet; studied classics at Trinity College, Dublin and Magdalen College, Oxford.

Most other pre-20th century Oxbridge playwrights, poets and English scholars studied Classics before English studies became a course in its own right.

Modern quotations about

- "Nor can I do better, in conclusion, than impress upon you the study of Greek literature, which not only elevates above the vulgar herd but leads not infrequently to positions of considerable emolument."

—Thomas Gaisford, Christmas sermon, Christ Church, Oxford. - "I would make them all learn English: and then I would let the clever ones learn Latin as an honour, and Greek as a treat."

—Sir Winston Churchill, Roving Commission: My Early Life - "He studied Latin like the violin, because he liked it."

—Robert Frost, The Death of the Hired Man - "I enquire now as to the genesis of a philologist and assert the following: 1. A young man cannot possibly know what the Greeks and Romans are. 2. He does not know whether he is suited for finding out about them."

—Friedrich Nietzsche, Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen - "I doubt whether classical education ever has been or can be successfully carried out without corporal punishment."

—George Orwell - "It's economically illiterate. A degree in Classics or Philosophy can be as valuable as anything else."

—Boris Johnson

See also

- Digital Classicist

- Humanism

- Literae Humaniores

- Loeb Classical Library

- Philology

- Western culture

- Western World

- Latin Language

- Greek Language

- Ancient Greece

- Ancient Rome

- Classical scholars

- Classics journals

Notes

- ↑ Werner Jaeger, Paideia, Eng. trans. 1939–44, vol. 2, p.xii.

- ↑ Edward Copleston, The Victorians and Ancient Greece, Richard Jenkyns, 60.

- ↑ J. and K. Kramer, La filologia classica, 1979 as quoted by [Christopher S. Mackay|http://www.ualberta.ca/~csmackay/Philology.html]

References

Dictionaries

- Biographical Dictionary of North American Classicists by Ward W. Briggs, Jr. (editor). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994 (hardcover, ISBN 0-313-24560-6).

- Classical Scholarship: A Biographical Encyclopedia (Garland Reference Library of the Humanities) by Ward W. Briggs and William M. Calder III (editors). New York: Taylor & Francis, 1990 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8240-8448-9).

- Dictionary of British classicists, 1500–1960 ed. Robert B. Todd (General editor). Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum, 2004 (ISBN 1-85506-997-0).

- An Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology, edited by Nancy Thomson de Grummond. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996 (hardcover, ISBN 0-313-22066-2; ISBN 0-313-30204-9 (A–K); ISBN 0-313-30205-7 (L–Z)).

- Harper's Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities, ed. by Harry Thurston Peck. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1896; 2nd ed., 1897; New York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1965.

- Medwid, Linda M. The Makers of Classical Archaeology: A Reference Work. New York: Humanity Books, 2000 (hardcover, ISBN 1-57392-826-7).

- The New Century Classical Handbook, ed. by Catherine B. Avery. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962.

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary, ed. by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, revised 3rd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003 (ISBN 0-19-860641-9).

- The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. by M.C. Howatson. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Miscellanea

- Beard, Mary; Henderson, John. Classics: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995 (paperback, ISBN 0-19-285313-9); 2000 (new edition, paperback, ISBN 0-19-285385-6).

- Briggs, Ward W.; Calder, III, William M. Classical scholarship: A biographical encyclopedia (Garland reference library of the humanities). London: Taylor & Francis, 1990 (ISBN 0-8240-8448-9).

- Forum: Class and Classics:

- Krevans, Nita. "Class and Classics: A Historical Perspective," The Classical Journal, Vol. 96, No. 3. (2001), p. 293.

- Moroney, Siobhan. "Latin, Greek and the American Schoolboy: Ancient Languages and Class Determinism in the Early Republic", The Classical Journal, Vol. 96, No. 3. (2001), pp. 295–307.

- Harrington Becker, Trudy. "Broadening Access to a Classical Education: State Universities in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century", The Classical Journal, Vol. 96, No. 3. (2001), pp. 309–322.

- Bryce, Jackson. "Teaching the Classics", The Classical Journal, Vol. 96, No. 3. (2001), pp. 323–334.

- Knox, Bernard. The Oldest Dead White European Males, And Other Reflections on the Classics. New York; London: W.W. Norton & Co., 1993.

- Macrone, Michael. Brush Up Your Classics. New York: Gramercy Books, 1991. (Guide to famous words, phrases and stories of Greek classics.)

- Nagy, Péter Tibor. "The meanings and functions of classical studies in Hungary in the 18th–20th century", in The social and political history of Hungarian education (ISBN 963-200-511-2).

- Wellek, René. "Classicism in Literature", in Dictionary of the History of Ideas, Studies of Selected Pivotal Ideas, ed. by Philip P. Wiener. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1968.

- Winterer, Caroline. The Mirror of Antiquity: American Women and the Classical Tradition, 1750–1900. Ithaca, NY; London: Cornell University Press, 2007 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-8014-4163-9).

External links

- The Classical Association, the largest classical organization in the UK.

- Institute of Classical Studies, the UK's national centre for the study of the ancient world, based at the University of London

- Institute of Classical Studies Postgraduate Work-in-Progress Seminar official website, the UK's national forum for postgraduate students in classics

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

- Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies

- The American Classical League, the largest classics organization in the US, mainly a Latin, Greek, and Humanities teacher resource center

- The National Junior Classical League, the largest youth-oriented Classics organization in the world, with US and international chapters, and membership for all middle- and high-school students of the Classics

- Classical Resources on Internet at the Department of Classical Philology, University of Tartu.

- De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors

- Electronic Resources for Classicists by the University of California, Irvine.

- Illustrated History of the Roman Empire

- The Online Medieval and Classical Library

- NOSTOI Journal of Classical Humanism. An aggregation of classical topics, articles and news.

- The Perseus Digital Library

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||