Chiang Kai-shek

- This is a Chinese name; the family name is Chiang.

| Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek 蔣中正 / 蔣介石 |

|

.jpg) |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office October 10, 1928 – December 15, 1931 |

|

| Premier | Tan Yankai Soong Tse-ven |

| Preceded by | Gu Weijun (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Lin Sen |

| In office August 1, 1943 – May 20, 1948 Acting until October 10, 1943 |

|

| Premier | Soong Tse-ven |

| Preceded by | Lin Sen |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as President of the Republic of China) |

|

1st-5th term President of the Republic of China

|

|

| In office May 20, 1948 – January 21, 1949 |

|

| Premier | Chang Chun Wong Wen-hao Sun Fo |

| Vice President | Li Zongren |

| Preceded by | Himself (as Chairman of the National Government of China) |

| Succeeded by | Li Zongren (Acting) |

| In office March 1, 1950 – April 5, 1975 |

|

| Premier | Yen Hsi-shan Chen Cheng Yu Hung-Chun Chen Cheng Yen Chia-kan Chiang Ching-kuo |

| Vice President | Li Zongren Chen Cheng Yen Chia-kan |

| Preceded by | Li Zongren (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Yen Chia-kan |

|

3rd, 7th, 9th, 11th Premier of the Republic of China

|

|

| In office December 4, 1930 – December 15, 1931 |

|

| Preceded by | Soong Tse-ven |

| Succeeded by | Chen Mingshu |

| In office December 7, 1935 – January 1, 1938 |

|

| President | Lin Sen |

| Preceded by | Wang Jingwei |

| Succeeded by | Hsiang-hsi Kung |

| In office November 20, 1939 – May 31, 1945 |

|

| President | Lin Sen |

| Preceded by | Hsiang-hsi Kung |

| Succeeded by | Soong Tse-ven |

| In office March 1, 1947 – April 18, 1947 |

|

| Preceded by | Soong Tse-ven |

| Succeeded by | Chang Chun |

|

1st, 3rd Director-General of the Kuomintang

|

|

| In office March 29, 1938 – April 5, 1975 |

|

| Preceded by | Hu Hanmin |

| Succeeded by | Chiang Ching-kuo (as Chairman of the Kuomintang) |

|

|

|

| Born | 31 October 1887 Fenghua, Qing Dynasty |

| Died | 5 April 1975 (aged 87) Taipei, Republic of China (Taiwan) |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Political party | Kuomintang |

| Spouse(s) | Mao Fumei Yao Yecheng (concubine) Chen Jieru Soong May-ling |

| Children | Chiang Ching-kuo Chiang Wei-kuo (adopted) |

| Alma mater | Imperial Japanese Army Academy |

| Occupation | Soldier (General officer) |

| Religion | Methodist[1] |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | General Special Class |

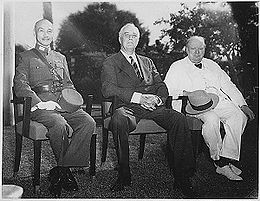

Chiang Kai-shek (traditional Chinese: 蔣中正 / 蔣介石; simplified Chinese: 蒋中正 / 蒋介石; pinyin: Jiǎng Jièshí; but see names below) (October 31, 1887 – April 5, 1975) was a political and military leader of 20th century China.

He was an influential member of the nationalist party Kuomintang (KMT) and Sun Yat-sen's close ally. He became the Commandant of Kuomintang's Whampoa Military Academy and took Sun's place in the party when the latter died in 1925. In 1928, Chiang led the Northern Expedition to unify the country, becoming China's overall leader.[2] He served as chairman of the National Military Council of the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 to 1948. Chiang led China in the Second Sino-Japanese War, during which the Nationalist Government's power severely weakened, but his prominence grew.

Chiang's Nationalists engaged in a long standing civil war with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Chiang attempted to eradicate the Communists. Ultimately, with support from the Soviet Union, the CCP defeated the Nationalists, forcing the Nationalist government to retreat to Taiwan, where martial law was continued while the government still tried to take back mainland China. Chiang ruled the island with an iron fist as the President of the Republic of China and Director-General of the Kuomintang until his death in 1975.

Feelings towards Chiang are mixed in Taiwan. While some still view him as a hero, others consider him with disdain; subsequently, hundreds of Chiang's statues have been dismantled across the island.[3]

Contents |

Early life

Chiang was born in Xikou, a town approximately 30 kilometers southwest of downtown Ningbo, in Fenghua, Ningbo, Zhejiang. However, his ancestral home, a concept important in Chinese society, was the town of Heqiao (和橋鎮) in Yixing, Wuxi, Jiangsu (approximately 38 km (24 mi) southwest of downtown Wuxi, and 10 km (6.2 mi) from the shores of Lake Tai).

Chiang's father, Chiang Zhaocong (蔣肇聰), and mother, Wang Caiyu (王采玉), were members of an upper-middle to upper class family of salt merchants. Chiang's father died when he was only eight years of age, and he wrote of his mother as the "embodiment of Confucian virtues." In an arranged marriage, Chiang was married to a fellow villager by the name of Mao Fumei.[4] Chiang and Mao had a son, Ching-kuo and a daughter Chien-hua.[5]

Chiang grew up in an era in which military defeats and civil wars among warlords had left China destabilized and in debt, and he decided to pursue a military career. He began his military education at the Baoding Military Academy, in 1906. He left for a preparatory school for Chinese students, the Imperial Japanese Army Academy, in Japan in 1907. There he was influenced by his compatriots to support the revolutionary movement to overthrow the Qing Dynasty and set up a Chinese republic. He befriended fellow Zhejiang native Chen Qimei, and, in 1908, Chen brought Chiang into the Tongmenghui, a precursor of the Kuomintang (KMT) organization. Chiang served in the Imperial Japanese Army from 1909 to 1911.

Returning to China in 1911 after learning of the outbreak of the Wuchang Uprising, Chiang intended to fight as an artillery officer. He served in the revolutionary forces, leading a regiment in Shanghai under his friend and mentor Chen Qimei, one of Sun's chief lieutenants. The Xinhai Revolution ultimately succeeded with the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty and Chiang became a founding member of the KMT.

After the takeover of the Republican government by Yuan Shikai and the failed Second Revolution, Chiang, like his KMT comrades, divided time between exile in Japan and the havens of the Shanghai International Settlement. In Shanghai, Chiang also cultivated ties with the underworld gangs dominated by the notorious Green Gang and its leader Du Yuesheng. On February 15, 1912, several KMT members, including Chiang, murdered Tao Chengzhang, the leader of the Restoration Society, in a Shanghai French Concession hospital.

On May 18, 1916 agents of Yuan Shikai assassinated Chen Qimei. Chiang succeeded Chen as leader of the Chinese Revolutionary Party in Shanghai. Sun Yat-sen's career was at its lowest point then, with most of his old Revolutionary Alliance comrades refusing to join him in the exiled Chinese Revolutionary Party.

In 1917, Sun Yat-sen moved his base of operations to Guangzhou and Chiang joined him in 1918. At this time Sun remained largely sidelined and, without arms or money, was soon expelled from Guangzhou and exiled again to Shanghai. He was restored to Guangzhou with mercenary help in 1920. However, a rift had developed between Sun, who sought to militarily unify China under the KMT, and Guangdong Governor Chen Jiongming, who wanted to implement a federalist system with Guangdong as a model province. On June 16, 1923 Chen attempted to assassinate Sun and had his residence shelled. During a prolonged skirmish between the troops of these opposing forces, Sun and his wife Soong Ching-ling narrowly escaped heavy machine gun fire and were rescued by gunboats under Chiang's direction. The incident earned Chiang the trust of Sun Yat-sen.

Sun regained control of Guangzhou in early 1924, again with the help of mercenaries from Yunnan, and accepted aid from the Comintern. Undertaking a reform of the KMT, he established a revolutionary government aimed at unifying China under the KMT. That same year, Sun sent Chiang to spend three months in Moscow studying the Soviet political and military system. During his trip in Russia, Chiang met Leon Trotsky and other Soviet leaders, but quickly drew to the conclusion that the Russian model was not suitable for China.[6] Chiang Kai-shek returned to Guangzhou and in 1924 was appointed Commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy by Sun. Chiang resigned from the office for one month in disagreement with Sun's too close cooperation with the Comintern, but returned at Sun's demand. The early years at Whampoa allowed Chiang to cultivate a cadre of young officers loyal to both the KMT and himself. Throughout his rise to power, Chiang also benefited from membership of the nationalist Tiandihui fraternity, to which Sun Yat-sen also belonged, and which remained a source of support during his leadership of China and later Taiwan.

Succession of Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen died on March 12, 1925,[7] creating a power vacuum in the Kuomintang (KMT). A contest ensued between Chiang, who stood at the right wing of the KMT, and Sun Yat-sen's close comrade-in-arms Wang Jingwei, who leaned towards the left. Although Wang succeeded Sun as Chairman of the National Government, Chiang's relatively low position in the party's internal hierarchy was bolstered by his military backing and political maneuvering following the Zhongshan Warship Incident. On June 5, 1926, Chiang became Commander-in-Chief of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA),[8] and on July 27 he launched a military campaign known as the Northern Expedition, to defeat the warlords controlling northern China and unify the country under the KMT.

The NRA branched into three divisions: to the west was Wang Jingwei, who led a column to take Wuhan; Bai Chongxi's column went east to take Shanghai; and Chiang himself led in the middle route to take Nanjing, before pressing ahead to capture Beijing. However, in January 1927, Wang Jingwei and his KMT leftist allies took the city of Wuhan amid much popular mobilization and fanfare. Allied with a number of Chinese Communists and advised by Soviet agent Mikhail Borodin, Wang declared the National Government as having moved to Wuhan. Having taken Nanking in March (and briefly visited Shanghai, now under the control of his close ally Bai Chongxi), Chiang halted his campaign and prepared a violent break with the leftist elements which he thought threatened his control of the KMT.

On April 12, Chiang carried out a purge of thousands of suspected Communists and dissidents in Shanghai and began large-scale massacres across the country. Throughout April 1927, more than 12,000 people were killed in Shanghai. The killings drove most Communists from urban cities and into the rural countryside where the KMT was less powerful.[9]

Now with an established a National Government in Nanjing, and supported by conservative allies including Hu Hanmin, Chiang's expulsion of the communists and their Soviet advisers led to the beginning of the Chinese Civil War. Wang Jingwei's National Government was weak militarily and soon overtaken by Chiang with a local warlord (Li Zongren of Guangxi). Eventually, Wang and his leftist party surrendered to Chiang and joined him in Nanjing. Finally, the warlord capital of Beijing was taken in June 1928 and in December the Manchurian warlord Zhang Xueliang pledged allegiance to Chiang's government.

Chiang attempted to cement himself as the official successor of Sun Yat-sen. In a pairing of great political significance, Chiang was Sun's brother-in-law: he had married Soong May-ling, the younger sister of Soong Ching-ling, Sun's widow, on December 1, 1927. Originally rebuffed by her in the early-1920s, Chiang managed to ingratiate himself to some degree with Soong May-ling's mother by first divorcing his wife and concubines, and promising to eventually convert to Christianity. He was baptized in the Methodist church in 1929, a year after his marriage to Soong. Upon reaching Beijing, Chiang paid homage to Sun Yat-sen and had his body moved to the new capital of Nanjing to be enshrined in a grand mausoleum.

Tutelage over China

Having gained control of China, Chiang's party remained surrounded by "surrendered" warlords who remained relatively autonomous within their own regions. On October 10, 1928, Chiang was named director of the State Council, the equivalent to President of the country, in addition to his other titles.[10] As with his predecessor Sun Yat-sen, the Western media dubbed him "Generalissimo".[8] According to Sun Yat-sen's plans, the Kuomintang (KMT) was to rebuild China in three steps: military rule, political tutelage, and constitutional rule. The ultimate goal of the KMT revolution was democracy, which was not yet feasible in China's fragmented state. Since the KMT had completed the first step of revolution through seizure of power in 1928, Chiang's rule thus began a period of what his party considered to be "political tutelage" in Sun Yat-sen's name. During this so-called Republican Era, many features of a modern, functional Chinese state emerged and developed.

The decade 1928 to 1937 saw some aspects of foreign imperialism, concessions and privileges in China moderated through diplomacy. The government acted to modernize the legal and penal systems, attempted to stabilize prices, amortize debts, reform the banking and currency systems, build railroads and highways, improve public health facilities, legislate against traffic in narcotics, and augment industrial and agricultural production - though not all were successful or completed. Strides were made towards furthering education standards and, in an effort to unify Chinese society, the so-called New Life Movement was launched to enforce Confucian moral values and personal discipline. Standard Mandarin, then known as Guoyu, was promoted as an standard tongue, and the establishment of communications facilities (including radio) were used to encourage a sense of Chinese nationalism that was not always possible due to the nation's fractured status.

Any successes that the Nationalists did make, however, were met with constant political and military upheavals. While much of the urban areas were now under the control of the KMT, the countryside remained under the influence of weakened yet undefeated warlords and Communists. Chiang often resolved issues of warlord obstinacy through military action, with one northern rebellion – against the warlords Yan Xishan and Feng Yuxiang – occurring in 1930 during the Central Plains War. The war almost bankrupted the government and caused almost 250,000 casualties on both sides. In 1931 Hu Hanmin, Chiang's old supporter, publicly voiced a popular concern that Chiang's position as both premier and president flew in the face of the democratic ideals of the Nationalist government. Chiang had Hu put under house arrest, but he was released after national condemnation, and went on to escape and establish a rival government in Guangzhou. The split resulted in military campaigns between Hu's Guangzhou government and its supporters, and Chiang's Nationalist government. Chiang only won due to a shift in allegiance by the warlord Zhang Xueliang, who had previously supported Hu Hanmin.

Throughout his rule, complete eradication of the Communists remained Chiang's dream. Having regrouped in Jiangxi, Chiang led his armies against the newly established Chinese Soviet Republic. With help from foreign military advisers, Chiang's Fifth Campaign finally surrounded the Chinese Red Army in 1934. The Communists, tipped-off that a Nationalist offensive was on the cards, retreated as part of the Long March, which saw Mao Zedong rise from a mere military official to the practical leader of the Chinese Communist Party.

Wartime leader of China

After the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Chiang resigned as Chairman of the National Government. He returned shortly, adopting the slogan "first internal pacification, then external resistance". However, this policy of avoiding a frontal war against the Japanese was widely unpopular. Especially so, when in 1932, while Chiang was seeking first to defeat the Communists, Japan launched an advance on Shanghai and bombarded Nanjing. This disrupted Chiang's offensives against the Communists for a time, although it was the northern factions of Hu Hanmin's Guangzhou (Canton) government (notably the 19th Route Army) that primarily led the offensive against the Japanese during this skirmish. Brought into the Nationalist army immediately after the battle, the 19th Route Army's career under Chiang would be cut short after it was disbanded for demonstrating socialist tendencies.

In December 1936, Chiang flew to Xi'an to coordinate a major assault on the Red Army and Communist Republic that had retreated into Yan'an. However, Chiang's allied commander Zhang Xueliang, whose forces were to be used in his attack and whose homeland of Manchuria had been invaded by the Japanese, had other plans. On December 12, Zhang and several other Nationalist generals kidnapped Chiang for two weeks in what is known as the Xi'an Incident. They forced Chiang into making a "Second United Front" with the Communists against Japan. Zhang was placed under house arrest and other generals who had assisted him were executed. The Second United Front was nominal at best and was all but broken up in 1941.

The Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in July 1937, and in August that year Chiang sent 600,000 of his best-trained and equipped soldiers to defend Shanghai. With over 200,000 Chinese casualties, Chiang lost the political cream of his Whampoa-trained officers. Though Chiang lost militarily, the battle dispelled Japanese claims it could conquer China in three months and demonstrated to the Western powers that the Chinese would continue the fight. By December, the capital city of Nanjing had fallen to the Japanese, and Chiang moved the government inland first to Wuhan and later to Chongqing. Devoid of economic and industrial resources, Chiang withdrew into the hinterlands, stretching the Japanese supply lines and bogging down Japanese soldiers in the vast Chinese interior. However, these scorched earth policies also resulted in many deaths, including the 1938 Yellow River flood, when dams were burst to delay the Japanese advance. Some 500,000 people are thought to have been killed.

The Japanese, controlling the puppet-state of Manchukuo and much of China's eastern seaboard, appointed Wang Jingwei as a Quisling-ruler of the occupied Chinese territories. Wang named himself President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government (not the same 'National Government' as Chiang's), and led a surprisingly large minority of anti-Chiang/anti-Communist Chinese against his old comrades. He died in 1944.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor and the opening of the Pacific War, China became one of the Allied Powers. During and after World War II, Chiang and his American-educated wife Soong May-ling, known in the United States as "Madame Chiang", held the support of the United States China Lobby which saw in them the hope of a Christian and democratic China. Chiang was even named the Supreme Commander of Allied forces in the China war zone. He was created a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath by King George VI of the United Kingdom in 1942.[11]

Losing Mainland China

In 1945 when Japan surrendered, Chiang's Chongqing government was ill-equipped and ill-prepared to reassert its authority in formerly Japanese-occupied China, and asked the Japanese to postpone their surrender until Kuomintang (KMT) authority could arrive to take over. This was an unpopular move among a population that, for many, had spent more than a decade under often brutal foreign occupation. American troops and weapons soon bolstered KMT forces, allowing them to reclaim cities. The countryside, however, remained mostly out of Nationalist hands.

Following the war, the United States encouraged peace talks between Chiang and Communist leader Mao Zedong in Chongqing. Due to concerns about widespread and well-documented corruption in Chiang's government throughout his rule (though not always with his knowledge), the U.S. government limited aid to Chiang for much of the period of 1946 to 1948, in the midst of fighting against the People's Liberation Army led by Mao Zedong. Alleged infiltration of the U.S. government by Chinese Communist agents may have also played a role in the aid suspension.[12] Others have pointed out that American arms and weapons continued to flow into Chiang's military, even as money did not.

Though Chiang had achieved status abroad as a world leader, his government was deteriorating as a result of corruption and inflation. In his diary on June 1948, Chiang wrote that the KMT had failed, not because of external enemies but because of rot from within.[13] The war had severely weakened the Nationalists, while the Communists were strengthened by popular land-reform[14], and a rural population that supported and trusted them. The Nationalists initially had superiority in arms and men; but their lack of popularity, infiltration by Communist agents, low morale, and disorganization soon allowed the Communists to gain the upper hand.

Meanwhile a new Constitution was promulgated in 1947, and Chiang was formally elected by the National Assembly as the first term President of the Republic of China on May 20, 1948. This marked the beginning of what was termed the 'democratic constitutional government' period by the KMT political orthodoxy, but the Communists refused to recognise the new Constitution and its government as legitimate. Chiang resigned as President on January 21, 1949, as KMT forces suffered bitter losses and defections to the Communists. Vice-President Li Zongren took over as Acting President, but his relationship with Chiang soon deteriorated. Li fled to the United States under the pretense of seeking medical treatment. Like many other KMT officials, Li absconded with millions of dollars of government money. Unlike the others, Li was later impeached by the Control Yuan.

In the early morning of December 10, 1949, Communist troops laid siege to Chengdu, the last KMT controlled city in mainland China, where Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo directed the defense at the Chengdu Central Military Academy. The aircraft May-ling evacuated them to Taiwan on the same day.

Presidency in Taiwan

Chiang moved the government to Taipei, Taiwan, where he formally resumed duties as President of the Republic of China on March 1, 1950.[15] Chiang was reelected by the National Assembly to be the President of the Republic of China (ROC) on May 20, 1954 and again in 1960, 1966, and 1972. He continued to claim sovereignty over all of China, including the territories held by his government and the People's Republic, as well as territory the latter ceded to foreign governments, such as Tuva and Outer Mongolia. In the context of the Cold War, most of the Western world recognized this position and the ROC represented "China" in the United Nations and other international organizations until the 1970s.

Despite the democratic constitution, the government under Chiang was a one-party state, consisting almost completely of mainlanders; the "Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion" greatly enhanced executive powers and the goal of retaking mainland China allowed the KMT to maintain a monopoly on power and prohibition of opposition parties. The government's official line for these martial law provisions stemmed from the claim that emergency provisions were necessary, since the Communists and Kuomintang (KMT) were still technically under a state of war. Seeking to promote Chinese nationalism, Chiang's government actively ignored and suppressed local cultural expression, even forbidding the use of local languages in mass media broadcasts or during class sessions. He was also the head of the White Terror, where hundreds of thousands of people were jailed and executed for being perceived as threats to the ROC government.

The government offered limited civil, economic freedom, property rights (personal and intellectual), among other liberties which permitted free debate within the confines of the legislature, but also jailed dissidents who were labeled by the KMT as supporters of communism or Taiwan independence. Later, Chiang's son, Chiang Ching-kuo, and Chiang Ching-kuo's successor, Lee Teng-hui, would, in the 1980s and 1990s, increase native Taiwanese representation in the government and loosen the many authoritarian controls of the early ROC-on-Taiwan era.

Under the pretext that new elections could not be held in Communist-occupied constituencies, the National Assembly, Legislative Yuan, and Control Yuan members held their posts indefinitely. It was also under the Temporary Provisions that Chiang was able to bypass term limits to remain as president. He was reelected by the National Assembly as president four times — doing so in 1954, 1960, 1966, and 1972.

Believing that corruption and a lack of morals were key reasons that the KMT lost mainland China to the Communists, Chiang attempted to purge corruption by dismissing members of the KMT previously accused of graft. Some major figures in the previous mainland China government, such as H. H. Kung and T. V. Soong, exiled themselves to the United States. Though politically authoritarian and, to some extent, dominated by government-owned industries, Chiang's new Taiwanese state also encouraged economic development, especially in the export sector. A popular sweeping Land Reform Act, as well as American foreign aid during the 1950s, laid the foundation for Taiwan's economic success, becoming one of the Four Asian Tigers.

Death

In 1975, 26 years after Chiang came to Taiwan, he died in Taipei at the age of 87. He had suffered a major heart attack and pneumonia in the months before and died from renal failure aggravated with advanced cardiac malfunction at 23:50 on April 5.

A month of mourning was declared. Chinese music composer Hwang Yau-tai wrote the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Song. In mainland China, however, Chiang's death was met with little apparent mourning and Communist state-run newspapers gave the brief headline "Chiang Kai-shek Has Died." Chiang's body was put in a copper coffin and temporarily interred at his favorite residence in Cihu, Dasi, Taoyuan. When his son Chiang Ching-kuo died in 1988, he was entombed in a separate mausoleum in nearby Touliao (頭寮). The hope was to have both buried at their birthplace in Fenghua if and when it was possible. In 2004, Chiang Fang-liang, the widow of Chiang Ching-kuo, asked that both father and son be buried at Wuchih Mountain Military Cemetery in Xizhi, Taipei County. Chiang's ultimate funeral ceremony became a political battle between the wishes of the state and the wishes of his family.

Chiang was succeeded as President by Vice President Yen Chia-kan and as Kuomintang party leader by his son Chiang Ching-kuo, who retired Chiang Kai-shek's title of Director-General and instead assumed the position of Chairman. Yen's presidency was interim; Chiang Ching-kuo, who was the Premier, became President after Yen's term ended three years later.

Public perception

Chiang's legacy has been target of heated debates because of the different views held about him. For some, Chiang was a national hero who led the victorious Northern Expedition against the Beiyang Warlords in 1927 and contributed to unify China and subsequenly led China to ultimate victory against Japan in 1945. Some blamed him for not doing enough against the Japanese forces in the lead-up to and during the Second Sino-Japanese War, preferring to keep his armies to fight the communists, or merely waiting and hoping that the United States would get involved. Some also see him as a champion of anti-communism, being a key figure during the formative years of the World Anti-Communist League. During the Cold War, he was also seen as the leader who led Free China and the bulwark against a possible communist invasion. However, Chiang presided over purges, political authoritarianism and graft during his tenure in mainland China, and ruled throughout a period of imposed martial law and White Terror in Taiwan. His governments were accused of being corrupt from before he even took power in 1928. He also allied with known criminals like Du Yuesheng for political and financial gains. Some opponents charge that Chiang's effort in developing Taiwan was mostly to make the island a strong base from which to one day return to mainland China, and that Chiang had little regard for the long term prosperity and well-being of the Taiwanese people.

Today, Chiang's popularity in Taiwan is divided along political lines, enjoying greater support among Kuomintang supporters. He is generally unpopular among Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) voters and supporters. In sharp contrast to his son, Chiang Ching-kuo, and to Sun Yat-sen, his memory is rarely invoked by current political parties, including the Kuomintang.

In the United States and Europe, Chiang was often perceived negatively as the one who lost China to the communists. His constant demands for Western support and funding also earned him the nickname of "Generalissimo Chiang Cash-My-Cheque". Finally, he has been criticized for his poor military skills. He would often issue unrealistic orders, or persistently try to fight unwinnable battles, leading to the loss of his best troops.[16]

In recent years, this view however has started to change. Chiang is now increasingly perceived as a man simply overwhelmed by the events in China, having to fight simultaneously communists, Japanese and provincial warlords while having to reconstruct and unify the country. His sincere, albeit often unsuccessful attempts to build a more powerful nation have been noted by scholars such as Jonathan Fenby and Rana Mitter. The latter wrote that, ironically, today's China is closer to Chiang's vision than to Mao Zedong's one. He argues that the Communists, since the 1980s, have essentially created the state envisioned by Chiang in the 1930s. Mitter concludes by writing that "one can imagine Chiang Kai-shek's ghost wandering round China today nodding in approval, while Mao's ghost follows behind him, moaning at the destruction of his vision".[17]

Names

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Like many other Chinese historical figures, Chiang used several names throughout his life. That inscribed in the genealogical records of his family is Jiang Zhoutai (Chinese: 蔣周泰; Wade–Giles: Chiang Chou-tai). This so-called "register name" (譜名) is the one under which his extended relatives knew him, and the one he used in formal occasions, such as when he got married. In deference to tradition, family members did not use the register name in conversation with people outside of the family. In fact, the concept of real or original name is not as clear-cut in China as it is in the Western world.

In honor of tradition, Chinese families waited a number of years before officially naming their offspring. In the meantime, they used a "milk name" (乳名), given to the infant shortly after his birth and known only to the close family. Thus, the actual name that Chiang received at birth was Jiang Ruiyuan (Chinese: 蔣瑞元; Wade–Giles: Chiang Jui-yuan).

In 1903, the 16-year-old Chiang went to Ningbo to be a student, and he chose a "school name" (學名). This was actually the formal name of a person, used by older people to address him, and the one he would use the most in the first decades of his life (as the person grew older, younger generations would have to use one of the courtesy names instead). (Colloquially, the school name is called "big name" (大名), whereas the "milk name" is known as the "small name" (小名).) The school name that Chiang chose for himself was Zhiqing (Chinese: 志清; Wade–Giles: Chi-ching; means "purity of intentions"). For the next fifteen years or so, Chiang was known as Jiang Zhiqing. This is the name under which Sun Yat-sen knew him when Chiang joined the republicans in Guangzhou in the 1910s.

In 1912, when Jiang Zhiqing was in Japan, he started to use Jiang Jieshi (Chinese: 蔣介石; Wade–Giles: Chiang Chieh-shih) as a pen name for the articles that he published in a Chinese magazine he founded (Voice of the Army—軍聲). (Jieshi is the pinyin romanization of the name, based on Mandarin, but the common romanized rendering is Kai-shek which is in Cantonese romanization. As the republicans were based in Guangzhou (a Cantonese speaking area), Chiang became known by Westerners under the Cantonese romanization of his courtesy name, while the family name as known in English seems to be the Mandarin pronunciation of his Chinese family name, transliterated in Wade-Giles). In mainland China, Jiang Jieshi is the name under which he is commonly known today.

Jieshi soon became his courtesy name (字). Some think the name was chosen from the classic Chinese book the I Ching; others note that the first character of his courtesy name is also the first character of the courtesy name of his brother and other male relatives on the same generation line, while the second character of his courtesy name shi (石—meaning "stone") suggests the second character of his "register name" tai (泰—the famous Mount Tai of China). Courtesy names in China often bore a connection with the personal name of the person. As the courtesy name is the name used by people of the same generation to address the person, Chiang soon became known under this new name.

Sometime in 1917 or 1918, as Chiang became close to Sun Yat-sen, he changed his name from Jiang Zhiqing to Jiang Zhongzheng (Chinese: 蔣中正; Wade–Giles: Chiang Chung-cheng). By adopting the name Chung-cheng ("central uprightness"), he was choosing a name very similar to the name of Sun Yat-sen, who was (and still is) known among Chinese as Zhongshan (中山—meaning "central mountain"), thus establishing a link between the two. The meaning of uprightness, rectitude, or orthodoxy, implied by his name, also positioned him as the legitimate heir of Sun Yat-sen and his ideas. Not surprisingly, the Chinese Communists always rejected the use of this name and it is not well-known in mainland China. However, it was readily accepted by members of the Chinese Nationalist Party and is the name under which Chiang Kai-shek is still commonly known in Taiwan. Often the name is shortened to Chung-cheng only (Chung-cheng in Wade-Giles). For many years passengers arriving at the Chiang Kai-shek International Airport were greeted by signs in Chinese welcoming them to the "Chung Cheng International Airport". Similarly, the monument erected to Chiang's memory in Taipei known in English as Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall was literally named "Chung Cheng Memorial Hall" in Chinese. In Singapore, Chung Cheng High School was named after him.

His name is also written in Taiwan as "The Late President Lord Chiang" (先總統 蔣公), where the one-character-wide space known as nuo tai shows respect; this practice has lost some popularity. However, he is still known as Lord Chiang (蔣公) (without the title or space), along with the name Chiang Chung-cheng, in Taiwan.

Wives

Mao Fumei (毛福梅, 1882–1939) Died in the Second Sino-Japanese War during a bombardment. Mother to his son and successor Chiang Ching-kuo. |

Yao Yecheng (姚冶誠, 1889–1972) Came to Taiwan and died in Taipei. |

Chen Jieru (陳潔如, 1906–1971) Lived in Shanghai. Moved to Hong Kong later and died there. |

Soong May-ling (宋美齡, 1897–2003) Moved to the United States after Chiang Kai-shek's death. Arguably his most famous wife. She bore him no children. |

According to the memoirs of Ch'en Chieh-ju (Chen Jieru), Chiang's second wife, she contracted gonorrhea from Chiang soon after their marriage. He told her that he acquired this disease after separating from his first wife and living with his concubine Yao Yecheng, as well as with many other women he consorted with. His doctor explained to her that Chiang had sex with her before completing his treatment for the disease. As a result, both Chiang and Ch'en Chieh-ju became sterile, which explains why he had only one child, by his first wife.[18]

See also

| Chiang Kai-shek | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 蔣介石 / 蔣中正 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒋介石 / 蒋中正 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

- Whampoa Military Academy

- Xi'an Incident

- Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall

- Chiang Kai-shek statues

- Cihu Presidential Burial Place

- Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Song

- Sino-German cooperation (1911–1941)

- History of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Claire Lee Chennault

- Flying Tigers

- Democide

- He was portrayed by Zhang Guoli in the 2009 movie The Founding of a Republic.

- He was portrayed by Wu Hsing-kuo in the 1997 movie The Soong Sisters (film).

Notes

- ↑ 蒋介石宋美龄结婚照入《上海大辞典》

- ↑ Zarrow, Peter Gue (2005). China in War and Revolution, 1895-1949. pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Leavey, Helen (2003-03-11). "Taiwan divided over Chiang's memory". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/2836725.stm. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ While married to Mao, Chiang adopted two concubines (concubinage was still a common practice for well-to-do, non-Christian males in China): he married Yao Yecheng (1889-1972) in 1912 and Chen Jieru (陳潔如, 1906-1971) in December 1921. Mao raised his adopted Wei-kuo. Chen had an adopted daughter in 1924, named Yaoguang (瑤光), who later adopted her mother's surname. Chen's autobiography refuted the idea that she was a concubine, instead claiming that by the time she married Chiang he had already been divorced Mao, and therefore was his wife.

- ↑ http://www.nndb.com/people/974/000086716/

- ↑ However, Chiang did send his eldest son, Ching-kuo, to study in Russia, though after his father's later split from the First United Front, Ching-kuo was forced to stay there as a hostage until 1937.

- ↑ Eileen, Tamura (1998). China: Understanding Its Past. pp. 174.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Taylor 2009, p. 57

- ↑ Mayhew, Bradley (March 2004). Shanghai (2nd ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 51. ISBN 978-1740593083. http://books.google.com/books?id=IAe97m8sgw0C&pg=PA51. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ Taylor 2009, p. 84

- ↑ "BATTLE OF ASIA: Land of Three Rivers". Time. 4 May 1942. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,777742,00.html?promoid=googlep. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Haynes, John Earl; Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, New Haven: Yale University Press (2000), ISBN 0300084625, pp. 142–145

- ↑ Hoover Institution - Hoover Digest - Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for China

- ↑ Ray Huang, cong dalishi jiaodu du Jiang Jieshi riji (Reading Chiang Kai-shek's dairy from a macro-history perspective), Chinatimes Publishing Press, Taipei, 1994, p. 441-3

- ↑ ROC Chronology: Jan 1911 - Dec 2000

- ↑ Fenby, Jonathan. History of Modern China. pp. 279.

- ↑ Mitter, Rana. Modern China. pp. 73.

- ↑ Chiang Kai-shek's Secret Past. p 83-85.

Further reading

- Ch'en Chieh-ju. 1993. Chiang Kai-shek's Secret Past: The Memoirs of His Second Wife. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-1825-4

- Crozier, Brian. 2009. The Man Who Lost China. ISBN 0-684-14686-X

- Fairbank, John King, and Denis Twitchett, eds. 1983. The Cambridge History of China: Volume 12, Republican China, 1912–1949, Part 1. ISBN 0521235413

- Fenby, Jonathan. 2003. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek and the China He Lost. The Free Press, ISBN 0-7432-3144-9

- Li, Laura Tyson. 2006. Madame Chiang Kai-shek: China's Eternal First Lady. Grove Press. ISBN 0802143229

- May, Ernest R. 2002. "1947-48: When Marshall Kept the U.S. out of War in China." Journal of Military History 66(4): 1001-1010. Issn: 0899-3718 Fulltext: in Swetswise and Jstor

- Pakula, Hannah, The Last Empress: Madame Chiang Kai-Shek and the Birth of Modern China (London, Weidenfeld, 2009). ISBN 9780297859758

- Romanus, Charles F., and Riley Sunderland. 1959. Time Runs Out in CBI. Official U.S. Army history online edition

- Sainsbury, Keith. 1985. The Turning Point: Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, and Chiang-Kai-Shek, 1943. The Moscow, Cairo, and Teheran Conferences. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192851721

- Seagrave, Sterling. 1996. The Soong Dynasty. Corgi Books. ISBN 0-552-14108-9

- Stueck, William. 1984. The Wedemeyer Mission: American Politics and Foreign Policy during the Cold War. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820307173

- Tang Tsou. 1963. America's Failure in China, 1941-50. University of California Press. ISBN 0226815161

- Taylor, Jay. 2009. The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts ISBN 978-0674033382

- Tuchman, Barbara W. 1971. Stillwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45. ISBN 0802138527

External links

- Obituary, NY Times, 6 April 1975, The Life of Chiang Kai-shek: A Leader Who Was Thrust Aside by Revolution

- ROC Government Biography

- Time magazine's "Man and Wife of the Year", 1937

- The National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall Official Site

- The Chungcheng Cultural and Educational Foundation

- Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek Association Hong Kong

- Order of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek supplementing the Act of Surrender—by Japan on September 9, 1945

- Family tree of his descendants (in Simplified Chinese)

- 1966 GIO Biographical video

- "The Memorial Song of Late President Chiang Kai-shek" (Ministry of National Defence of ROC)

- Chiang Kai-shek Biography—From Spartacus Educational

- The Collected Wartime Messages Of Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek at archive.org

- The National Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Center Official Site

- Chiang Kai-shek Diaries at the Hoover Institution Archives

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Tan Yankai |

Chairman of the National Government of China 1928–1931 |

Succeeded by Lin Sen |

| Preceded by Soong Tse-ven |

Premier of the Republic of China 1930–1931 |

Succeeded by Chen Mingshu |

| Preceded by Wang Jingwei |

Premier of the Republic of China 1935–1938 |

Succeeded by Hsiang-hsi Kung |

| Preceded by Hsiang-hsi Kung |

Premier of the Republic of China 1939–1945 |

Succeeded by Song Ziwen |

| Preceded by Lin Sen |

Chairman of the National Government of China 1943–1948 |

Succeeded by Himself As President of the Republic of China |

| Preceded by Song Ziwen |

Premier of the Republic of China 1947 |

Succeeded by Zhang Qun |

| Preceded by Himself As Chairman of the National Government of China |

President of the Republic of China 1948–1949 |

Succeeded by Li Zongren Acting |

| Preceded by Li Zongren Acting |

President of the Republic of China 1950–1975 |

Succeeded by Yen Chia-kan |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Wang Jingwei |

Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang 1933–1938 |

Succeeded by Office abolished |

| Preceded by Hu Hanmin |

Director-General of the Kuomintang 1938–1975 |

Succeeded by Chiang Ching-kuo As Chairman of the Kuomintang |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by Office created |

Commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army 1925–1947 |

Succeeded by Office abolished |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Office created |

Commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy 1924–1947 |

Succeeded by Guan Linzheng |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Main events pre-1945 | Main events post-1945 | Specific articles |

|---|---|---|

|

Part of the Cold War

|

Primary participants |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||