Chesapeake Bay

| Chesapeake Bay | |

| Estuary | |

The Chesapeake Bay – Landsat photo

|

|

| Name origin: Chesepiooc, Algonquian for village "at a big river" | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| States | Maryland, Virginia |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Chester River, Choptank River, Nanticoke River, Pocomoke River |

| - right | Patapsco River, Patuxent River, Potomac River, Rappahannock River, York River, James River |

| Source | Susquehanna River |

| - location | Havre de Grace, MD |

| - elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| - coordinates | |

| Mouth | Atlantic Ocean |

| - location | Virginia Beach, VA |

| - elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| - coordinates | |

| Length | 200 mi (322 km) |

| Width | 30 mi (48 km) |

| Depth | 46 ft (14 m) |

| Basin | 64,299 sq mi (166,534 km²) |

| Area | 4,479 sq mi (11,601 km²) |

Chesapeake Bay Watershed

|

|

The Chesapeake Bay (pronounced /ˈtʃɛsəpiːk/, CHESS-ə-peek) is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers 64,299 square miles (166,534 km2) in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia.[1] More than 150 rivers and streams drain into the Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay is approximately 200 miles (300 km) long, from the Susquehanna River in the north to the Atlantic Ocean in the south. At its narrowest point between Kent County's Plum Point (near Newtown) and the Harford County shore near Romney Creek, the Bay is 2.8 miles (4.5 km) wide; at its widest point, just south of the mouth of the Potomac River, it is 30 miles (50 km) wide. Total shoreline for the Bay and its tributaries is 11,684 miles (18,804 km), and the surface area of the bay and its major tributaries is 4,479 square miles (11,601 km2). Average depth of the bay is 46 feet (14 m) and the maximum depth is 208 feet (63 m).

The bay is spanned in two places. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge crosses the bay in Maryland from Sandy Point (near Annapolis) to Kent Island; the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel in Virginia connects Virginia Beach to Cape Charles.

The word Chesepiooc is an Algonquian word referring to a village "at a big river." It is the seventh oldest surviving English place-name in the U.S., first applied as "Chesepiook" by explorers heading north from the Roanoke Colony into a Chesapeake tributary in 1585 or 1586.[2] In 2005, Algonquian linguist Blair Rudes "helped to dispel one of the area's most widely held beliefs: that 'Chesapeake' means something like 'Great Shellfish Bay.' It doesn't, Rudes said. The name might actually mean something like 'Great Water,' or it might have been just a village at the bay's mouth."[3] In contrast with many similar bodies of water, such as Delaware Bay or San Francisco Bay, the Chesapeake Bay is almost always preceded by the article the in usage.

Contents |

Geology

The Chesapeake Bay is the ria, or drowned valley, of the Susquehanna, meaning that it was where the river flowed when the sea level was lower. It is not a fjord, as the Laurentide Ice Sheet never reached as far south as the northernmost point on the bay.

The Bay's geology, its present form, and its very location were created by a bolide impact event at the end of the Eocene (about 35.5 million years ago), forming the Chesapeake Bay impact crater and the Susquehanna river valley much later. The Bay itself was formed starting about 10,000 years ago when rising sea levels at the end of the last ice age flooded the Susquehanna river valley.[1] Parts of the bay, especially the Calvert County, Maryland coastline, are lined by cliffs composed of deposits from receding waters millions of years ago. These cliffs, generally known as Calvert Cliffs, are famous for their fossils, especially fossilized shark teeth, which are commonly found washed up on the beaches next to the cliffs. Scientists' Cliffs is a beach community in Calvert County named for the desire to create a retreat for scientists when the community was founded in 1935.[4]

Much of the bay is quite shallow. At the point where the Susquehanna River flows into the bay, the average depth is 30 feet (9 m), although this soon diminishes to an average of 10 feet (3 m) from the city of Havre de Grace for about 35 miles (56 km), to just north of Annapolis. On average, the depth of the bay is 21 feet (7 meters), including tributaries;[5] over 24% of the bay is less than 6 ft (2 m) deep.

The climate of the area surrounding the bay is primarily humid subtropical, with hot, very humid summers and cold to mild winters. Only the area around the mouth of the Susquehanna River is continental in nature, and the mouth of the Susquehanna River and the Susquehanna flats often freeze in winter. It is exceedingly rare for the surface of the bay to freeze in winter, as happened most recently in the winter of 1976-1977.[6]

Since the bay is an estuary, it has fresh water, salt water and brackish water. Brackish water has three salinity zones — oligohaline, mesohaline, and polyhaline. The fresh water zone runs from the mouth of the Susquehanna River to north Baltimore. The oligohaline zone has very little salt. Salinity varies from 0.5 ppt to 10 ppt and freshwater species can survive there. The north end of the oligohaline zone is north Baltimore and the south end is the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. The mesohaline zone has a medium amount of salt and runs from the Bay Bridge to the mouth of the Rappahannock River. Salinity there ranges from 10.7 ppt to 18 ppt. The polyhaline zone is the saltiest zone and some of the water can be as salty as sea water. It runs from the mouth of the Rappahannock River to the mouth of the bay. The salinity ranges from 18.7 ppt to 36 ppt. (36 ppt is as salty as the ocean.)

History

Spanish explorer Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón sent an expedition out from Hispaniola in 1525, led by Captain Pedro de Quejo, which reached the mouth of the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays. It may have been the first European expedition to explore parts of the Chesapeake Bay, which the Spaniards called "Bahía de Santa María" at the time.[7] De Ayllón established a short-lived Spanish mission settlement, San Miguel de Gualdape, in 1526 along the Atlantic coast. Many scholars doubt the assertion that it was as far north as the Chesapeake; most place it in present-day Georgia's Sapelo Island.[8]

Captain John Smith of England explored and mapped the bay between 1607 and 1609. There was a mass migration of southern English cavaliers and their Irish and Scottish servants to the Chesapeake Bay Region between 1640 and 1675. The "Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail", the United States' first-ever all-water National Historic Trail, was created in July 2006. The bill passed by voice vote in the House of Representatives and by unanimous consent in the Senate.[9]

The Chesapeake Bay was the site of the Battle of the Chesapeake in 1781, during which the French fleet defeated the Royal Navy in the decisive naval battle of the American Revolutionary War.

Today, the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant uses water from the bay to cool its reactor.

The bay is also known for the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, a dog breed developed in this area.

Watershed

The largest rivers flowing directly into the bay, from north to south, are:

- Susquehanna River

- Patapsco River

- Chester River

- Choptank River

- Patuxent River

- Nanticoke River

- Potomac River

- Pocomoke River

- Rappahannock River

- York River

- James River

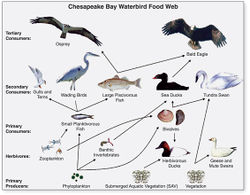

Flora and fauna

The Chesapeake Bay is home to numerous fauna that either migrate to the Bay at some point during the year or live there year round. There are over 300 species of fish and numerous shellfish and crab species. Some of these include the Atlantic menhaden, Striped bass, American eel, Eastern oyster, and the Blue crab. The Bay also houses various reptiles along with waterfowl like the American Osprey and the Bald Eagle.

Numerous flora also make the Chesapeake Bay their home both on land and underwater. Common submerged aquatic vegetation includes eelgrass and widgeon grass. Other vegetation that makes its home in other parts of the Bay are wild rice, various trees like the red maple and bald cypress, and spartina grass and phragmites.[10]

Fishing industry

The bay is mostly known for its great seafood production, especially blue crabs, clams and oysters. The plentiful oyster harvests led to the development of the skipjack, the state boat of Maryland, which is the only remaining working boat type in the United States still under sail power. Other characteristic bay area workboats include:[11]

- the log canoe

- the pungy

- the bugeye

- the Chesapeake Bay deadrise

Today, the body of water is less productive than it used to be, because of runoff from urban areas (mostly on the Western Shore) and farms (especially on the Eastern Shore), over harvesting, and invasion of foreign species. The bay still yields more fish and shellfish (about 45,000 short tons or 40,000 tonnes yearly) than any other estuary in the United States.

The bay is famous for its rockfish, also known as striped bass. Once on the verge of extinction, rockfish have made a significant comeback due to legislative action that put a moratorium on rockfishing, which allowed the species to repopulate. Rockfish are now able to be fished in strictly controlled and limited quantities.

Oyster farming is a growing industry for the bay to help maintain the bay's productivity as well as a natural effort for filtering impurities in the bay in an effort to reduce the disastrous effects of man-made pollution.

In 2005, local governments began debate on the introduction to certain parts of the bay of a species of Asian oyster, to revive the lagging shellfish industry.

Deteriorating environmental conditions

In the 1970s, the Chesapeake Bay was discovered to contain one of the planet's first identified marine dead zones, where hypoxic waters were so depleted of oxygen they were unable to support life, resulting in massive fish kills. Today the bay's dead zones are estimated to kill 75,000 tons of bottom-dwelling clams and worms each year, weakening the base of the estuary's food chain and robbing the blue crab in particular of a primary food source. Crabs themselves are sometimes observed to amass on shore to escape pockets of oxygen-poor water, a behavior known as a "crab jubilee". Hypoxia results in part from large algal blooms, which are nourished by the runoff of farm and industrial waste throughout the watershed. The runoff and pollution have many components that help contribute to the algal blooms which is mainly fed by phosphorus and nitrogen.[12] This algae prevents sunlight from reaching the bottom of the bay while alive and deoxygenates the bay's water when it dies and rots. The erosion and runoff of sediment into the bay, exacerbated by devegetation, construction and the prevalence of pavement in urban and suburban areas, also blocks vital sunlight. The resulting loss of aquatic vegetation has depleted the habitat for much of the bay's animal life. Beds of eelgrass, the dominant variety in the southern bay, have shrunk by more than half there since the early 1970s. Overharvesting, pollution, sedimentation and disease has turned much of the bay's bottom into a muddy wasteland.[13]

One particularly harmful source of toxicity is Pfiesteria piscicida, which can affect both fish and humans. Pfiesteria caused a small regional panic in the late 1990s when a series of large blooms started killing large numbers of fish while giving swimmers mysterious rashes, and nutrient runoff from chicken farms was blamed for the growth.[14]

Depletion of oysters

While the bay's salinity is ideal for oysters, and the oyster fishery was at one time the bay's most commercially viable,[15] the population has in the last fifty years been devastated. Maryland once had roughly 200,000 acres of oyster reefs. Today it has about 36,000.[15] It has been estimated that in pre-colonial times, oysters could filter the entirety of the Bay in about 3.3 days; by 1988 this time had increased to 325 days.[16] The harvest's gross value decreased 88% from 1982 to 2007.[17]

The primary problem is overharvesting. Lax government regulations allow anyone with a license to remove oysters from state-owned beds, and although limits are set, they are not strongly enforced.[15] The overharvesting of oysters has made it difficult for them to reproduce, which requires close proximity to one another. A second cause for the oyster depletion is that the drastic increase in human population caused a sharp increase in pollution flowing into the bay.[15]

The bay's oyster industry has also suffered from two diseases: MSX and Dermo.[18]

Oyster recovery attempts

The depletion of oysters due to overharvesting and damaged habitat has had a particularly harmful effect on the quality of the bay. Oysters serve as natural water filters, and their decline has further reduced the water quality of the bay. Water that was once clear for meters is now so turbid that a wader may lose sight of their feet before their knees are wet.

Efforts of federal, state and local governments, working in partnership through the Chesapeake Bay Program, and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and other nonprofit environmental groups, to restore or at least maintain the current water quality have had mixed results. One particular obstacle to cleaning up the bay is that much of the polluting substances arise far upstream in tributaries lying within states far removed from the bay itself. Despite the state of Maryland spending over $100 million to restore the bay, conditions have continued to grow worse. Twenty years ago, the bay supported over six thousand oystermen. There are now fewer than 500.[19]

Efforts to repopulate the bay with via hatcheries have been carried out by a group called the Oyster Recovery Partnership, with some success. They recently placed 6 million oysters on eight acres of the Trent Hall sanctuary.[20] Scientists from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at the College of William & Mary claim that experimental reefs created in 2004 now house 180 million native oysters, Crassostrea virginica, which is far less than the billions that once existed.[21]

Tourism

The Chesapeake Bay is a main feature for tourists who visit Maryland and Virginia each year. Fishing, crabbing, swimming, boating, and sailing are extremely popular activities enjoyed on the waters of the Chesapeake Bay. As a result, tourism has a notable impact on Maryland's economy.

See also

- Chesepian

- Delmarva Peninsula

- Dead zone (ecology)

- Chesapeake, a novel by author James A. Michener

- Chessie (sea monster)

- National Estuarine Research Reserve System

- List of islands in Maryland (with the islands in the bay)

- Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation

- Chesapeake Climate Action Network

- Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Fact Sheet 102-98 - The Chesapeake Bay: Geologic Product of Rising Sea Level". U. S. Geological Survey. 1998-11-18. http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs102-98/. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ Also shown as "Chisupioc" (by John Smith) and "Chisapeack", in Algonquian "Che" means "big" or "great", "sepi" means river, and the "oc" or "ok" ending indicated something (a village, in this case) "at" that feature. "Sepi" is also found in another placename of Algonquian origin, Mississippi. The name was soon transferred by the English from the big river at that site to the big bay. Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: Random House. p. 23.

- ↑ Farenthold, David A. (2006-12-12). "A Dead Indian Language Is Brought Back to Life". The Washington Post: p. A1. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/12/11/AR2006121101474_2.html?nav=rss_email/components. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ "FAQ". Scientists Cliffs community. http://www.scientistscliffs.org/HTML/FAQs/FAQs.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ↑ "Geography". Chesapeake Bay Foundation. http://www.cbf.org/site/PageServer?pagename=exp_sub_watershed_geography. Retrieved 2008-04-21. Other sources give values of 25 feet (e.g. "Charting the Chesapeake 1590-1990". Maryland State Archives. http://www.msa.md.gov/msa/speccol/sc2200/sc2269/html/chartfront.html. Retrieved 2008-04-21.) or 30 feet deep ("Healthy Chesapeake Waterways" (PDF). University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. http://ian.umces.edu/pdfs/iannewsletter1.pdf. Retrieved 2008-04-21.)

- ↑ "The Big Freeze". Time. 1977-01-31. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,918620-2,00.html. Retrieved 2007-03-19

- ↑ Grymes, Charles A. "Spanish in the Chesapeake". http://www.virginiaplaces.org/settleland/spanish.html. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- ↑ Weber, David (1994). The Spanish Frontier in North America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 36, 37.

- ↑ "H.R. 5466 [109th] Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Designation Act". GovTrack.us. http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h109-5466. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Domes S., Lewis M., Moran R., Nyman D.. “Chesapeake Bay Wetlands”. Emporia State University. May 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ↑ "Chesapeake Bay Workboats". Chesapeake Bay Gateway Network. http://www.baygateways.net/workboats.cfm. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ Dennen, R. (2009-10-30). “Is it time we put the ailing Bay on diet?”. The Free Lance Star. Retrieved 2010-02-17

- ↑ "Bad Water and the Decline of Blue Crabs in the Chesapeake Bay". Chesapeake Bay Foundation. 2008-12. http://www.cbf.org/Document.Doc?id=172. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ↑ Fahrenthold, David A. (2008-09-12). "Md. Gets Tough on Chicken Farmers". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/09/11/AR2008091103841.html.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Oysters: Gem of the Ocean, The Economist, December 8, 2008; accessed September 2, 2009.

- ↑ "Oyster Reefs: Ecological importance". US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://habitat.noaa.gov/restorationtechniques/public/habitat.cfm?HabitatID=2&HabitatTopicID=11. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ↑ "Estimating Net Present Value in the Northern Chesapeake Bay Oyster Fishery". NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office. 2008-11-07. http://www.nao.usace.army.mil/OysterEIS/PeerReviews/ResearchDocs/OysterNPV1107_rev_1.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ↑ "Research – Shellfish Diseases". Virginia Institute of Marine Science. 2007-03-16. http://www.vims.edu/env/research/shellfish/. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Urbina, Ian (November 29, 2008). In Maryland, Focus on Poultry Industry Pollution. The New York Times. p. A14. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/29/us/29poultry.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

- ↑ Program turns pork into oysters, Jesse Yeatman, South Maryland Newspapers Online, August 12, 2009.

- ↑ Oysters Are on the Rebound in the Chesapeake Bay, Henry Fountain, The New York Times, August 3, 2009; accessed September 8, 2009.

Further reading

- Cleaves, E.T. et al. (2006). Quaternary geologic map of the Chesapeake Bay 4º x 6º quadrangle, United States [Miscellaneous Investigations Series; Map I-1420 (NJ-18)]. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Phillips, S.W., ed. (2007). Synthesis of U.S. Geological Survey science for the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem and implications for environmental management [U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1316]. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

Bay area publications

- The Capital Newspaper – The news of the Chesapeake's western shore and Annapolis

- Chesapeake Bay Magazine – Lifestyle magazine concerning the Chesapeake Bay region

- PropTalk – Chesapeake Bay powerboating magazine

- SpinSheet – Chesapeake Bay sailing magazine

External links

- Bay Backpack – Chesapeake Bay education resources for educators

- Chesapeake Bay Foundation

- Chesapeake Research Consortium

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

- Chesapeake Bay Program

- Chesapeake Bay Journal

- Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network

- Chesapeake Community Modeling Program

- Chesapeake Bay Bridge (near Annapolis, MD)

- Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel

- Maryland Sea Grant

- National Geographic- Saving The Chesapeake

- National Geographic- Exploring The Chesapeake Then and Now

- National Geographic Magazine Jamestown/Werowocomoco Interactive

- Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Water Trail.

- University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Research and science application activities emphasizing Chesapeake Bay and its watershed.

- Chesapeake Bay Health Report Card

- Always-Updated Event Calendar for the Chesapeake Bay.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||