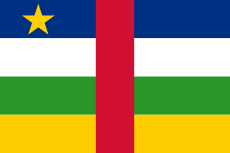

Central African Republic

| Central African Republic

République centrafricaine

Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Unité, Dignité, Travail" (French) "Unity, Dignity, Work" |

||||||

| Anthem: La Renaissance (French) E Zingo (Sango) |

||||||

|

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Bangui |

|||||

| Official language(s) | Sango, French | |||||

| Demonym | Central African | |||||

| Government | Republic | |||||

| - | President | François Bozizé | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Faustin-Archange Touadéra | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Independence | from France | |||||

| - | Date | August 13, 1960 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 622,984 km2 (43rd) 240,534 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2009 estimate | 4,422,000[1] (124th) | ||||

| - | 2003 census | 3,895,150 | ||||

| - | Density | 7.1/km2 (223rd) 18.4/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2009 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $3.309 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $745[2] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2009 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $1.986 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $447[2] | ||||

| Gini (1993) | 61.3 (high) | |||||

| HDI (2007) | ||||||

| Currency | Central African CFA franc (XAF) |

|||||

| Time zone | WAT (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+1) | ||||

| Drives on the | right[3] | |||||

| Internet TLD | .cf | |||||

| Calling code | 236 | |||||

The Central African Republic (CAR) (French: République centrafricaine, pronounced: [ʁepyblik sɑ̃tʁafʁikɛn], or Centrafrique [sɑ̃tʀafʀik]; Sango Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka), is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It borders Chad in the north, Sudan in the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo in the south, and Cameroon in the west. The CAR covers a land area of almost 623,000 km², and has an estimated population of about 4.4 million as per 2008. Bangui is the capital city.

Most of the CAR consists of Sudano-Guinean savannas but it also includes a Sahelo-Sudanian zone in the north and an equatorial forest zone in the south. Two thirds of the country lies in the basins of the Ubangi River, which flows south into the Congo River, while the remaining third lies in the basin of the Chari River, which flows north into Lake Chad.

Since most of the territory locates in the Ubangi and Shari river basins, France called the colony it carved out in this region Ubangi-Chari, or Oubangui-Chari in French. It became a semi-autonomous territory of the French Community in 1958 and then an independent nation on 13 August 1960. For over three decades after independence, the CAR was ruled by presidents who were not chosen in multi-party democratic elections or took power by force. Local discontent with this system was eventually reinforced by international pressure, following the end of the Cold War.

The first multi-party democratic elections were held in 1993 with resources provided by the country's donors and help from the UN Office for Electoral Affairs, and brought Ange-Félix Patassé to power. He lost popular support during his presidency and was overthrown in 2003 by French-backed General François Bozizé, who went on to win a democratic election in May 2005. Inability to pay workers in the public sector led to strikes in 2007, forcing the resignation of the government in early 2008. A new Prime Minister, Faustin-Archange Touadéra, was named on January 22, 2008.

The Central African Republic is one of the poorest countries in the world and among the ten poorest countries in Africa. The Human Development Index for the Central African Republic is 0.369, which gives the country a rank of 179 out of 182 countries with data.[4] In 2001 though, The Ecologist magazine estimated that the Central African Republic is the world's leading country in sustainable development.[5]

Contents |

History

Early history

Between about 1000 BC and 1000 AD, Adamawa-Eastern-speaking peoples spread eastward from Cameroon to Sudan and settled in most of the territory of the CAR. During the same period, a much smaller number of Bantu-speaking immigrants settled in Southwestern CAR and some Central Sudanic-speaking populations settled along the Oubangi.

The majority of the CAR's inhabitants thus speak Adamawa-Eastern languages or Bantu languages belonging to the Niger-Congo family. A minority speak Central Sudanic languages of the Nilo-Saharan family. More recent immigrants include many Muslim merchants who most often speak Arabic or Hausa.

Exposure to the outside world

Until the early 1800s, the peoples of the CAR lived beyond the expanding Islamic frontier in the Sudanic zone of Africa and thus had relatively little contact with Abrahamic religions or northern economies. During the first decades of the nineteenth century, however, Muslim traders began increasingly to penetrate the region of the CAR and to cultivate special relations with local leaders in order to facilitate their trade and settlement in the region.

The initial arrival of Muslim traders in the early 1800s was relatively peaceful and depended upon the support of local peoples, but after about 1850, slave traders with well-armed soldiers began to penetrate the region. Between c. 1860 and 1910, slave traders from Sudan, Chad, Cameroon, Dar al-Kuti in Northern CAR and Nzakara and Zande states in Southeastern CAR exported much of the population of Eastern CAR, a region with very few inhabitants today.

French colonialism

European penetration of Central African territory began in the late nineteenth century during the so-called Scramble for Africa (c. 1875–1900). Count Savorgnan de Brazza took the lead in establishing the French Congo with headquarters in the city named after him, Brazzaville, and sent expeditions up the Ubangi River in an effort to expand France's claims to territory in Central Africa. King Leopold II of Belgium, Germany and the United Kingdom also competed to establish their claims to territory in the Central African region.

In 1889 the French established a post on the Ubangi River at Bangui, the future capital of Ubangi-Shari and the CAR. De Brazza then sent expeditions in 1890–91 up the Sangha River in what is now Southwestern CAR, up the center of the Ubangi basin toward Lake Chad, and eastward along the Ubangi River toward the Nile. De Brazza and the procolonial in France wished to expand the borders of the French Congo to link up with French territories in West Africa, North Africa and East Africa.

In 1894, the French Congo's borders with Leopold II's Congo Free State and German Cameroon were fixed by diplomatic agreements. Then, in 1899, the French Congo's border with Sudan was fixed along the Congo-Nile watershed, leaving France without her much coveted outlet on the Nile and turning Southeastern Ubangi-Shari into a cul-de-sac.

Once European negotiators agreed upon the borders of the French Congo, France had to decide how to pay for the costly occupation, administration, and development of the territory. The reported financial successes of Leopold II's concessionary companies in the Congo Free State convinced the French government in 1899 to grant 17 private companies large concessions in the Ubangi-Shari region. In return for the right to exploit these lands by buying local products and selling European goods, the companies promised to pay rent to the colonial state and to promote the development of their concessions. The companies employed European and African agents who frequently used extremely brutal and atrocious methods to force Central Africans to work for them. At the same time, the French colonial administration began to force Central Africans to pay taxes and to provide the state with free labor. The companies and French administration often collaborated in their efforts to force Central Africans to work for their benefit, but they also often found themselves at odds.

Some French officials reported abuses committed by private company militias and even by their own colonial colleagues and troops, but efforts to bring these criminals to justice almost always failed. When news of atrocities committed against Central Africans by concessionary company employees and colonial officials or troops reached France and caused an outcry, there were investigations and some feeble attempts at reform, but the situation on the ground in Ubangi-Shari remained essentially the same.

In the meantime, during the first decade of French colonial rule (c. 1900–1910), the rulers of African states in the Ubangi-Shari region increased their slave raiding activities and also their sale of local products to European companies and the colonial state. They took advantage of their treaties with the French to procure more weapons which were used to capture more slaves and so much of the eastern half of Ubangi-Shari was depopulated as a result of the export of Central Africans by local rulers during the first decade of colonial rule. Those who had power, Africans and Europeans, often made life miserable for those who did not have the power to resist.

During the second decade of colonial rule (c. 1910–1920), armed employees of private companies and the colonial state continued to use brutal methods to deal with local populations who resisted forced labor but the power of local African rulers was destroyed and so slave raiding was greatly diminished. In 1911, the Sangha and Lobaye basins were ceded to Germany as part of an agreement which gave France a free-hand in Morocco and so Western Ubangi-Shari came under German rule until World War I, during which France reconquered this territory by using Central African troops.

The third decade of colonial rule (1920–1930) was a period of transition during which a network of roads was built, cash crops were promoted, mobile health services were formed to combat sleeping sickness, and Protestant missions established stations in different parts of the country. New forms of forced labor were also introduced, however, as the French conscripted large numbers of Ubangians to work on the Congo-Ocean Railway and many of these recruits died of exhaustion and illness.

In 1925 the French writer André Gide published Voyage au Congo in which he described the alarming consequences of conscription for the Congo-Ocean railroad and exposed the continuing atrocities committed against Central Africans in Western Ubangi-Shari by employees of the Forestry Company of Sangha-Ubangi, for example. In 1928 a major insurrection, the Kongo-Wara 'war of the hoe handle' broke out in Western Ubangi-Shari and continued for several years. The extent of this insurrection, perhaps the largest anticolonial rebellion in Africa during the interwar years, was carefully hidden from the French public because it provided evidence, once again, of strong opposition to French colonial rule and forced labor.

During the fourth decade of colonial rule (c. 1930–1940), cotton, tea, and coffee emerged as important cash crops in Ubangi-Shari and the mining of diamonds and gold began in earnest. Several cotton companies were granted purchasing monopolies over large areas of cotton production and were thus able to fix the prices paid to cultivators in order to assure profits for their shareholders. Europeans established coffee plantations and Central Africans also began to cultivate coffee.

The fifth decade of colonial rule (c. 1940–1950) was shaped by the Second World War and the political reforms which followed in its wake. In September 1940 pro-Gaullist French officers took control of Ubangi-Shari.

Independence

On 1 December 1958 the colony of Ubangi-Shari became an autonomous territory within the French Community and took the name Central African Republic. The founding father and president of the Conseil de Gouvernement, Barthélémy Boganda, died in a mysterious plane accident in 1959, just eight days before the last elections of the colonial era. On 13 August 1960 the Central African Republic gained its independence and two of Boganda's closest aides, Abel Goumba and David Dacko, became involved in a power struggle. With the backing of the French, Dacko took power and soon had Goumba arrested. By 1962 President Dacko had established a one-party state.

On 31 December 1965 Dacko was overthrown in the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état by Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa, who suspended the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly. President Bokassa declared himself President for life in 1972, and named himself Emperor Bokassa I of the Central African Empire on 4 December 1976. A year later, Emperor Bokassa crowned himself in a lavish and expensive ceremony that was ridiculed by much of the world. In 1979 France carried out a coup against Bokassa and "restored" Dacko to power. Dacko, in turn, was overthrown in a coup by General André Kolingba on 1 September 1981.

Kolingba suspended the constitution and ruled with a military junta until 1985. He introduced a new constitution in 1986 which was adopted by a nationwide referendum. Membership in his new party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Centrafricain (RDC) was voluntary. In 1987, semi-competitive elections to parliament were held and municipal elections were held in 1988. Kolingba's two major political opponents, Abel Goumba and Ange-Félix Patassé, boycotted these elections because their parties were not allowed to compete.

By 1990, inspired by the fall of the Berlin Wall, a pro-democracy movement became very active. In May 1990 a letter signed by 253 prominent citizens asked for the convocation of a National Conference but Kolingba refused this request and detained several opponents. Pressure from the United States, more reluctantly from France, and from a group of locally represented countries and agencies called GIBAFOR (France, USA, Germany, Japan, EU, World Bank and UN) finally led Kolingba to agree, in principle, to hold free elections in October 1992, with help from the UN Office of Electoral Affairs. After using the excuse of alleged irregularities to suspend the results of the elections as a pretext for holding on to power, President Kolingba came under intense pressure from GIBAFOR to establish a "Conseil National Politique Provisoire de la République" (Provisional National Political Council) (CNPPR) and to set up a "Mixed Electoral Commission" which included representatives from all political parties.

When elections were finally held in 1993 (again with the help of the international community) Ange-Félix Patassé led in the first round and Kolingba came in fourth behind Abel Goumba and David Dacko. In the second round, Patassé won 53 percent of the vote while Goumba won 45.6 percent. Most of Patassé's support came from Gbaya, Kare and Kaba voters in seven heavily populated prefectures in the northwest while Goumba's support came largely from ten less-populated prefectures in the south and east. Furthermore, Patassé's party, the Mouvement pour la Libération du Peuple Centrafricain (MLPC) or Movement for the Liberation of the Central African People gained a simple but not an absolute majority of seats in parliament, which meant Patassé needed coalition partners.

Patassé relieved former President Kolingba of his military rank of general in March 1994 and then charged several former ministers with various crimes. Patassé also removed many Yakoma from important, lucrative posts in the government. Two hundred mostly Yakoma members of the presidential guard were also dismissed or reassigned to the army. Kolingba's RDC loudly proclaimed that Patassé's government was conducting a "witch hunt" against the Yakoma.

A new constitution was approved on 28 December 1994 and promulgated on 14 January 1995, but this constitution, like those before it, did not have much impact on the practice of politics. In 1996–1997, reflecting steadily decreasing public confidence in its erratic behaviour, three mutinies against Patassé's government were accompanied by widespread destruction of property and heightened ethnic tension. On 25 January 1997, the Bangui Peace Accords were signed which provided for the deployment of an inter-African military mission, the Mission Interafricaine de Surveillance des Accords de Bangui (MISAB). Mali's former president, Amadou Touré, served as chief mediator and brokered the entry of ex-mutineers into the government on 7 April 1997. The MISAB mission was later replaced by a U.N. peacekeeping force, the Mission des Nations Unies en RCA (MINURCA).

In 1998 parliamentary elections resulted in Kolingba' RDC winning 20 out of 109 seats, which constituted a comeback, but in 1999, notwithstanding widespread public anger in urban centers with his corrupt rule, Patassé won free elections to become president for a second term.

On 28 May 2001 rebels stormed strategic buildings in Bangui in an unsuccessful coup attempt. The army chief of staff, Abel Abrou, and General François N'Djadder Bedaya were shot, but Patassé regained the upper hand by bringing in at least 300 troops of the rebel leader Jean-Pierre Bemba (from across the river in the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and by Libyan soldiers.

In the aftermath of this failed coup, militias loyal to Patassé sought revenge against rebels in many neighborhoods of the capital, Bangui, that resulted in the destruction of many homes as well as the torture and murder of many opponents. Eventually Patassé came to suspect that General François Bozizé was involved in another coup attempt against him and so Bozizé fled with loyal troops to Chad. In March 2003, Bozizé launched a surprise attack against Patassé, who was out of the country. Libyan troops and some 1,000 soldiers of Bemba's Congolese rebel organization failed to stop the rebels, who took control of the country and thus succeeded in overthrowing Patassé.

François Bozizé suspended the constitution and named a new cabinet which included most opposition parties. Abel Goumba, "Mr. Clean", was named vice-president, which gave Bozizé's new government a positive image. Bozizé established a broad-based National Transition Council to draft a new constitution and announced that he would step down and run for office once the new constitution was approved. A national dialogue was held from 15 September to 27 October 2003, and Bozizé won a fair election that excluded Patassé, to be elected president on a second ballot, in May 2005.

Humanitarian aid, peacebuilding, and development

The Central African Republic is heavily dependent upon multilateral foreign aid and the presence of numerous NGOs which provide services which the government fails to provide. As one UNDP official put it, the CAR is a country "sous serum", or a country metaphorically hooked up to an IV. (Mehler 2005:150). The very presence of numerous foreign personnel and organizations in the country, including peacekeepers and even refugee camps, provides an important source of revenue for many Central Africans.

The country is self-sufficient in food crops, but much of the population lives at a subsistence level. Livestock development is hindered by the presence of the tsetse fly.

In 2006 due to ongoing violence, over 50,000 in the country's north-west were at risk of starvation,[6] and this was only averted thanks to United Nations support.

Peacebuilding Commission

On 12 June 2008, the Central African Republic became the fourth country to be placed on the agenda of the UN Peacebuilding Commission,[7] which was set up in 2005 to help countries emerging from conflict avoid the slide back into war or chaos. The 31-member body agreed to take up the situation after a request from the government.

Peacebuilding Fund

The Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon declared on 8 January 2008 that the Central African Republic was eligible to receive assistance from the Peacebuilding Fund.[8] Three priority areas were identified: 1) Security sector reform 2) Promotion of good governance and the rule of law and 3) Revitalization of communities affected by conflicts.

Politics

François Bozizé is President of the country. A new constitution was approved by voters in a referendum held on December 5, 2004. Full multiparty presidential and parliamentary elections were held in March 2005,[9] with a second round in May. Bozizé was declared the winner after a run-off vote.[10]

In February 2006, there were reports of widespread violence in the northern part of the CAR.[11] Thousands of refugees fled their homes, caught in the crossfire of battles between government troops and rebel forces. More than 7,000 people fled to neighboring Chad. Those who remained in the CAR told of government troops systematically killing men and boys suspected of cooperating with rebels.[12]

In March 2010, François Bozizé signed a decree declaring presidential elections on April 25, 2010.[13] The elections were first postponed to 16 May, and then indefinitely.[14] It is unclear when the Central African Republic general election, 2010 will be held.

Prefectures and sub-prefectures

The Central African Republic is divided into 14 administrative prefectures (préfectures), along with 2 economic prefectures (préfectures economiques) and one autonomous commune. The prefectures are further divided into 71 sub-prefectures (sous-préfectures).

The prefectures include:

- Bamingui-Bangoran

- Basse-Kotto

- Haute-Kotto

- Haut-Mbomou

- Kémo

- Lobaye

- Mambéré-Kadéï

- Mbomou

- Nana-Mambéré

- Ombella-M'Poko

- Ouaka

- Ouham

- Ouham-Pendé

- Vakaga

the two economic prefectures are Nana-Grébizi and Sangha-Mbaéré; the commune is Bangui.

Geography

The Central African Republic is a land-locked nation within the interior of the African continent. It is bordered by the countries of Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo.

Much of the country consists of flat, or rolling plateau savanna, typically about 1,640 feet (500 m) above sea level, of which most of the northern half lies within the World Wildlife Fund's East Sudanian savanna ecoregion. In the northeast are the Fertit Hills, and there are scattered hills in southwest part of the country. To the northwest is the Yade Massif, a granite plateau with an altitude of 3,750 feet (1,143 m).

At 240,519 square miles (622,941 km2), the Central African Republic is the world's 42nd-largest country. It is comparable in size to the Ukraine, and is somewhat smaller than the US state of Texas.

Much of the southern border is formed by tributaries of the Congo River, with the Mbomou River in the east merging with the Uele River to form the Ubangi River. In the west, the Sangha River flows through part of the country. The eastern border lies along the edge of the Nile river watershed.

Estimates of the amount of the country covered by forest ranges up to 8%, with the densest parts in the south. The forest is highly diverse, and includes commercially important species of Ayous, Sapelli and Sipo.[15] The deforestation rate is 0.4% per annum, and lumber poaching is commonplace.[16]

In the November 2008 issue of National Geographic, the Central African Republic was named the country least affected by light pollution.

Climate

The climate of the C.A.R. is generally tropical. The northern areas are subject to harmattan winds, which are hot, dry, and carry dust. The northern regions have been subject to desertification, and the northeast is a desert. The remainder of the country is prone to flooding from nearby rivers.

Economy

The economy of the CAR is dominated by the cultivation and sale of food crops such as cassava, peanuts, maize, sorghum, millet, sesame, and plantain . The annual real GDP growth rate is just above 3%. The importance of foodcrops over exported cash crops is indicated by the fact that the total production of cassava, the staple food of most Central Africans, ranges between 200,000 and 300,000 tons a year, while the production of cotton, the principal exported cash crop, ranges from 25,000 to 45,000 tons a year. Foodcrops are not exported in large quantities but they still constitute the principal cash crops of the country because Central Africans derive far more income from the periodic sale of surplus foodcrops than from exported cash crops such as cotton or coffee.

The CAR's largest import partner is South Korea (20.2%), followed by France (13.6%) and Cameroon (7.7%), while its largest export partner is Japan (40.4%), followed by Belgium (9.8%) and China (8.2%).[17][18]

Many rural and urban women also transform foodcrops into alcoholic drinks such as sorghum beer or hard liquor and derive considerable income from the sale of these drinks. Much of the income derived from the sale of foods and alcohol is not "on the books" and thus is not considered in calculating per capita income, which is one reason why official figures for per capita income are not accurate in the case of the CAR.

The per capita income of the CAR is often listed as being around $300 a year, said to be one of the lowest in the world, but this figure is based mostly on reported sales of exports and largely ignores the more important but unregistered sale of foods, locally produced alcohol, diamonds, ivory, bushmeat, and traditional medicine, for example. The informal economy of the CAR is more important than the formal economy for most Central Africans.

Diamonds constitute the most important export of the CAR, accounting for 40–55% of export revenues, but an estimated 30–50% of the diamonds produced each year leave the country clandestinely. Export trade is hindered by poor economic development, and the location of this country far from the coast.

The wilderness regions of this country have potential as ecotourist destinations. The country is noted for its population of forest elephants. In the southwest, the Dzanga-Sangha National Park is a rain forest area. To the north, the Manovo-Gounda St Floris National Park has been well-populated with wildlife, including leopards, lions, and rhinos. To the northeast the Bamingui-Bangoran National Park. However the population of wildlife in these parks has severely diminished over the past 20 years due to poaching, particularly from the neighboring Sudan.

The CAR is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[19]

The CAR is ranked 180 out of 181 on 'ease of business' in the 2009 Doing Business Report of the World Bank Group. The 'ease of business' ranking uses a composite index on regulations that enhance business activity and those that constrain it.[20]

Demographics

The population has almost quadrupled since independence. In 1960 the population was 1,232,000. Now the population is 4,422,000. (2009 UN est.) Note: estimates for this country take into account the effects of excess mortality due to AIDS; this can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality and death rates, lower population and growth rates, and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex than would otherwise be expected.

The United Nations estimates that approximately 11% of the population aged 15 – 49 is HIV positive.[21] Only 3% of the country has antiretroviral therapy available, compared to 17% coverage in neighbouring countries of Chad and the Republic of the Congo.[22]

The nation is divided into over 80 ethnic groups, each having its own language. The largest ethnic groups are the Baya (33%), Banda (28%), Mandjia (7%), Sara (10%), Mboum (7%), M'Baka (4%), Yakoma (4%), and Fulani (3%), with others constituting 4%, including Europeans of mostly French descent.

Health

Female life expectancy at birth was 48.2 and male life expectancy at birth was at 45.1 in 2007.[23] The fertility rate is at about five births per woman.[23] Government expenditure on health was at US$ 20 (PPP) per person in 2006.[23] There were 8 physicians per 100,000 people in 2004.[24] Government expenditure on health was at 10.9 % of total government expenditure in 2006.[23]

Religion

Christians form 50 percent of the population, while 35 percent of the population maintain Indigenous beliefs. Islam is practiced by approximately 15 percent of the country's population.[25]

There are many missionary groups operating in the country, including Lutherans, Baptists, Catholics, Grace Brethren, and Jehovah's Witnesses. While these missionaries are predominantly from the United States, France, Italy, and Spain, many are also from Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and other African countries. Many missionaries left the country due to fighting between rebel and government forces in 2002 and 2003. Many have now returned to the country and resumed their activities.[26]

Culture

Music

Education

Public education in the Central African Republic is free, and education is compulsory from ages 6 to 14.[27] About half the adult population of the country is illiterate.[28] The University of Bangui, a public university located in Bangui, is the only institution of higher education in the Central African Republic.

See also

- List of Central African Republic-related topics

- Transport in the Central African Republic

References

- ↑ Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2009) (PDF). World Population Prospects, Table A.1. 2008 revision. United Nations. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2008/wpp2008_text_tables.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Central African Republic". International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2007&ey=2010&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=626&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a=&pr.x=87&pr.y=20. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Which side of the road do they drive on? Brian Lucas. August 2005. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ↑ List of countries by Human Development Index

- ↑ "HS Foreign 24.4.2001 – Did the Central African Republic surpass Finland in environmental affairs?". .hs.fi. http://www2.hs.fi/english/archive/news.asp?id=20010424IE1. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "Thousands could die of starvation, says United Nations spokesperson Maurizio Giuliano". http://www.irinnews.org/report.aspx?reportid=58581.

- ↑ "Peacebuilding Commission Places Central African Republic On Agenda; Ambassador Tells Body ‘Car Will Always Walk Side By Side With You, Welcome Your Advice’". Un.org. 2008-07-02. http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2008/pbc39.doc.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Reuters AlertNet – CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: Polls results to be announced on 22 May, official says". Alertnet.org. 2005-05-11. http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/IRIN/87ba6e292f78b0bc6dbbaeb9c2ef6bd9.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "Timeline: Central African Republic". BBC News. 9 March 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/country_profiles/1067615.stm. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Thousands flee new CAR 'rebels'". BBC News. 24 February 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4747772.stm. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Thousands flee from CAR violence". BBC News. 25 March 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4844664.stm. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Central African Republic to hold April 25 elections | Top News | Reuters". Af.reuters.com. 2010-02-25. http://af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFJOE61O0OQ20100225. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "BozizĂŠ prend ses prĂŠcautions Afrique Subsaharienne, Politique". Jeuneafrique.com. 2010-05-15. http://www.jeuneafrique.com/Article/ARTJAWEB20100511115353/politique-elections-presidentielle-francois-bozizebozize-prend-ses-precautions.html. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ Sold Down the River (English) March 2001, Forests Monitor

- ↑ The Forests of the Congo Basin: State of the Forest 2006. CARPE 13-July-07

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2050.html?countryName=China&countryCode=ch®ionCode=eas&#ch

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2061.html?countryName=China&countryCode=ch®ionCode=eas&#ch

- ↑ "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". http://www.ohada.com/index.php. Retrieved 2009-03-22

- ↑ http://www.doingbusiness.org/Documents/CountryProfiles/CAF.pdf

- ↑ "Countries". Unaids.org. 2008-07-29. http://www.unaids.org/en/Regions_Countries/Countries/central_african_republic.asp. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ http://data.unaids.org/pub/GlobalReport/2006/2006_GR_ANN3_en.pdf

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "Human Development Report 2009 - Central African Republic". Hdrstats.undp.org. http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/data_sheets/cty_ds_CAF.html. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "WHO Country Offices in the WHO African Region - WHO | Regional Office for Africa". Afro.who.int. http://www.afro.who.int/home/countries/fact_sheets/car.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ the World Factbook

- ↑ "U.S. Department of State". State.gov. 2005-09-20. http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/71292.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "Central African Republic". Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor (2001). Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Central African Republic - Statistics". UNICEF. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/car_statistics.html. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

Further reading

- Kalck, Pierre, Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic, 2004

- Petringa, Maria, Brazza, A Life for Africa (2006) ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- Titley, Brian, Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa, 2002

External links

- Government

- Overviews

- Country Profile from BBC News

- Central African Republic entry at The World Factbook

- Central African Republic from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Central African Republic at the Open Directory Project

- Wikimedia Atlas of the Central African Republic

- News

- Humanitarian news and analysis from IRIN – Central African Republic

- Humanitarian information coverage on ReliefWeb

- Central African Republic news headline links from AllAfrica.com

- Tourism

- Central African Republic travel guide from Wikitravel

- Other

- Central African Republic at Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team (HDPT)

- Central African Republic reports from Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers

- Johann Hari in Birao, Central African Republic Inside France's Secret War from The Independent, October 5, 2007

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||