Cassini–Huygens

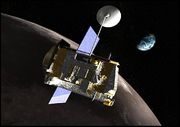

Artist's concept of Cassini's Saturn Orbit Insertion maneuver |

|

| Operator | NASA/ESA/ASI |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Fly-by, orbiter, and lander |

| Flyby of | Jupiter, Venus, Earth, 2685 Masursky, Saturn's moons |

| Satellite of | Saturn |

| Launch date | 1997-10-15 08:43:00 UTC 13 years, 3 months, and 30 days elapsed |

| Launch vehicle | Titan IV-B/Centaur rocket |

| COSPAR ID | 1997-061A |

| Homepage | Cassini Equinox home |

Cassini–Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/ASI robotic spacecraft mission currently studying the planet Saturn and its many natural satellites. The spacecraft consists of two main elements: the NASA-designed and -constructed Cassini orbiter, named for the Italian-French astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, and the ESA-developed Huygens probe, named for the Dutch astronomer, mathematician and physicist Christiaan Huygens. The complete Cassini space probe was launched on October 15, 1997, and after a long interplanetary voyage, it entered into orbit around Saturn on July 1, 2004. On December 25, 2004, the Huygens probe was separated from the orbiter at approximately 02:00 UTC. Then, it reached Saturn's moon Titan on January 14, 2005, when it made a descent into Titan's atmosphere, and downwards to the surface, radioing scientific information back to the Earth by telemetry. On April 18, 2008, NASA announced a two-year extension of the funding for ground operations of this mission, at which point it was renamed to Cassini Equinox Mission.[1] This was again extended in February 2010 and the mission may potentially continue until 2017. Cassini is the fourth space probe to visit Saturn and the first to enter orbit.

16 European countries and the United States make up the team responsible for designing, building, flying and collecting data from the Cassini orbiter and Huygens probe. The mission is managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the United States, where the orbiter was designed and assembled. Development of the Huygens Titan probe was managed by the European Space Research and Technology Centre, whose prime contractor for the probe was the Alcatel company in France. Equipment and instruments for the probe were supplied from many countries. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) provided the Cassini probe's high-gain radio antenna, and a compact and lightweight radar, which acts in multipurpose as a synthetic aperture radar, a radar altimeter, and a radiometer.

Objectives

Cassini has seven primary objectives:

- Determine the three-dimensional structure and dynamic behavior of the rings of Saturn

- Determine the composition of the satellite surfaces and the geological history of each object

- Determine the nature and origin of the dark material on Iapetus's leading hemisphere

- Measure the three-dimensional structure and dynamic behavior of the magnetosphere

- Study the dynamic behavior of Saturn's atmosphere at cloud level

- Study the time variability of Titan's clouds and hazes

- Characterize Titan's surface on a regional scale

The Cassini–Huygens spacecraft was launched on October 15, 1997, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station's Space Launch Complex 40 using a U.S. Air Force Titan IVB/Centaur rocket. The complete launcher was made up of a two-stage Titan IV booster rocket, two strap-on solid rocket motors, the Centaur upper stage, and a payload enclosure, or fairing.

The total cost of this scientific exploration mission is about US$3.26 billion, including $1.4 billion for pre-launch development, $704 million for mission operations, $54 million for tracking and $422 million for the launch vehicle. The United States contributed $2.6 billion (80%), the ESA $500 million (15%), and the ASI $160 million (5%).

The primary mission for Cassini ended on July 30, 2008. However, given the excellent condition of the orbiter, the mission was extended to the end of June 2010 (Cassini Equinox Mission). This studied the Saturn system in detail during Equinox, which happened in August 2009.[1] On February 3, 2010, NASA announced another extension for Cassini, this one for 6-1/2 years until 2017, the time of Summer Solstice in Saturn's Northern Hemisphere (Cassini Solstice Mission). The extension enables another 155 revolutions around the planet, 54 flybys of Titan and 11 flybys of Enceladus.[2] In 2017, an encounter with Titan will change its orbit in such a way that, at closest approach to Saturn, it will be only three thousand km above the planet's cloudtops, below the inner edge of the D ring. This sequence of "proximal orbits" will end when another encounter with Titan sends the probe into Saturn's atmosphere.

History

Cassini–Huygens's origins date to 1982, when the European Science Foundation and the American National Academy of Sciences formed a working group to investigate future cooperative missions. Two European scientists suggested a paired Saturn Orbiter and Titan Probe as a possible joint mission. In 1983, NASA's Solar System Exploration Committee recommended the same Orbiter and Probe pair as a core NASA project. NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) performed a joint study of the potential mission from 1984 to 1985. ESA continued with its own study in 1986, while the American astronaut Sally Ride, in her influential 1987 report "NASA Leadership and America's Future in Space", also examined and approved of the Cassini mission.

While Ride's report described the Saturn orbiter and probe as a NASA solo mission, in 1988 the Associate Administrator for Space Science and Applications of NASA Len Fisk returned to the idea of a joint NASA and ESA mission. He wrote to his counterpart at the ESA, Roger Bonnet, strongly suggesting that the ESA choose the Cassini mission from the three candidates at hand and promising that NASA would commit to the mission as soon as the ESA did.

At the time, NASA was becoming more sensitive to the strain that had developed between the American and European space programs as a result of European perceptions that NASA had not treated it like an equal during previous collaborations. NASA officials and advisers involved in promoting and planning Cassini–Huygens attempted to correct this trend by stressing their desire to evenly share any scientific and technology benefits resulting from the mission. In part, this newfound spirit of cooperation with Europe was driven by a sense of competition with the Soviet Union, which had begun to cooperate more closely with Europe as the ESA drew further away from NASA.

The collaboration not only improved relations between the two space programs but also helped Cassini–Huygens survive congressional budget cuts in the United States. Cassini–Huygens came under fire politically in both 1992 and 1994, but NASA successfully persuaded the U.S. Congress that it would be unwise to halt the project after the ESA had already poured funds into development because frustration on broken space exploration promises might spill over into other areas of foreign relations. The project proceeded politically smoothly after 1994, although, as noted below, citizens' groups concerned about its potential environmental impact attempted to derail it through protests and lawsuits until and past its 1997 launch.

Spacecraft design

The spacecraft was originally planned to be the second three-axis stabilized, RTG-powered Mariner Mark II, a class of spacecraft developed for missions beyond the orbit of Mars. Cassini was being developed together with the Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby (CRAF) spacecraft, but various budget cuts and rescopings of the project forced NASA to terminate CRAF development in order to save Cassini. As a result, the Cassini spacecraft became a more specialized design, canceling the implementation of the Mariner Mark II series.

The spacecraft, including the orbiter and the probe, is the largest and most complex interplanetary spacecraft built to date. The orbiter has a mass of 2,150 kg (4,700 lb), the probe 350 kg (770 lb). With the launch vehicle adapter and 3,132 kg (6,900 lb) of propellants at launch, the spacecraft had a mass of about 5,600 kg (12,000 lb). Only the two Phobos spacecraft sent to Mars by the Soviet Union were heavier. The Cassini spacecraft is more than 6.8 meters (22 ft) high and more than 4 meters (13 ft) wide. The complexity of the spacecraft is necessitated both by its trajectory (flight path) to Saturn, and by the ambitious program of scientific observations once the spacecraft reaches its destination. It functions with 1,630 interconnected electronic components, 22,000 wire connections, and over 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) of cabling.

Now that the Cassini probe is orbiting Saturn, it is between 8.2 and 10.2 astronomical units from the Earth. Because of this, it takes between 68 to 84 minutes for radio signals to travel from Earth to the spacecraft, and vice-versa. Thus, ground controllers cannot give "real-time" instructions to the spacecraft, either for day-to-day operations, or in cases of unexpected events. Even if they responded immediately after becoming aware of a problem, nearly three hours will have passed before the satellite receives a response.

Instruments

Cassini's instrumentation consists of: a synthetic aperture radar mapper, a charge-coupled device imaging system, a visible/infrared mapping spectrometer, a composite infrared spectrometer, a cosmic dust analyzer, a radio and plasma wave experiment, a plasma spectrometer, an ultraviolet imaging spectrograph, a magnetospheric imaging instrument, a magnetometer and an ion/neutral mass spectrometer. Telemetry from the communications antenna and other special transmitters (an S-band transmitter and a dual-frequency Ka-band system) will also be used to make observations of the atmospheres of Titan and Saturn and to measure the gravity fields of the planet and its satellites.

- Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS)

- The CAPS is a direct sensing instrument that measures the energy and electrical charge of particles that the instrument encounters, (the amount of electrons and protons in the particle). CAPS will measure the molecules originating from Saturn's ionosphere and also determine the configuration of Saturn's magnetic field. CAPS will also investigate plasma in these areas as well as the solar wind within Saturn's magnetosphere.[3][4]

- Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA)

- The CDA is a direct sensing instrument that measures the size, speed, and direction of tiny dust grains near Saturn. Some of these particles are orbiting Saturn, while others may come from other star systems. The CDA on the orbiter is designed to learn more about these mysterious particles, the materials in other celestial bodies and potentially about the origins of the universe.[3]

- Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS)

- The CIRS is a remote sensing instrument that measures the infrared waves coming from objects to learn about their temperatures, thermal properties, and compositions. Throughout the Cassini–Huygens mission, the CIRS will measure infrared emissions from atmospheres, rings and surfaces in the vast Saturn system. It will map the atmosphere of Saturn in three dimensions to determine temperature and pressure profiles with altitude, gas composition, and the distribution of aerosols and clouds. It will also measure thermal characteristics and the composition of satellite surfaces and rings.[3]

- Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS)

- The INMS is a direct sensing instrument that analyzes charged particles (like protons and heavier ions) and neutral particles (like atoms) near Titan and Saturn to learn more about their atmospheres. INMS is intended also to measure the positive ion and neutral environments of Saturn's icy satellites and rings.[3][5][6]

- Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS)

- The ISS is a remote sensing instrument that captures most images in visible light, and also some infrared images and ultraviolet images. The ISS has taken hundreds of thousands of images of Saturn, its rings, and its moons, for return to the Earth by radio telemetry. The ISS has a wide-angle camera (WAC) that takes pictures of large areas, and a narrow-angle camera (NAC) that takes pictures of small areas in fine detail. Each of these cameras uses a sensitive charge-coupled device (CCD) as its electromagnetic wave detector. Each CCD has a 1,024 square array of pixels, 12 μm on a side. Both cameras allow for many data collection modes, including on-chip data compression. Both cameras are fitted with spectral filters that rotate on a wheel—to view different bands within the electromagnetic spectrum ranging from 0.2 to 1.1 μm.[3][7]

- Dual Technique Magnetometer (MAG)

- The MAG is a direct sensing instrument that measures the strength and direction of the magnetic field around Saturn. The magnetic fields are generated partly by the intensely hot molten core at Saturn's center. Measuring the magnetic field is one of the ways to probe the core, even though it is far too hot and deep to visit. MAG aims to develop a three-dimensional model of Saturn's magnetosphere, and determine the magnetic state of Titan and its atmosphere, and the icy satellites and their role in the magnetosphere of Saturn.[3][8]

- Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI)

- The MIMI is both a direct and remote sensing instrument that produces images and other data about the particles trapped in Saturn's huge magnetic field, or magnetosphere. This information will be used to study the overall configuration and dynamics of the magnetosphere and its interactions with the solar wind, Saturn's atmosphere, Titan, rings, and icy satellites.[3][9]

- Radar

- The onboard radar is a remote active and remote passive sensing instrument that will produce maps of Titan's surface. It measures the height of surface objects (like mountains and canyons) by sending radio signals that bounce off Titan's surface and timing their return. Radio waves can penetrate the thick veil of haze surrounding Titan. The radar will listen for radio waves that Saturn or its moons may be producing.[3]

- Radio and Plasma Wave Science instrument (RPWS)

- The RPWS is a direct and remote sensing instrument that receives and measures radio signals coming from Saturn, including the radio waves given off by the interaction of the solar wind with Saturn and Titan. RPWS is to measure the electric and magnetic wave fields in the interplanetary medium and planetary magnetospheres. It will also determine the electron density and temperature near Titan and in some regions of Saturn's magnetosphere. RPWS studies the configuration of Saturn's magnetic field and its relationship to Saturn Kilometric Radiation (SKR), as well as monitoring and mapping Saturn's ionosphere, plasma, and lightning from Saturn's (and possibly Titan's) atmosphere.[3]

- Radio Science Subsystem (RSS)

- The RSS is a remote sensing instrument that uses radio antennas on Earth to observe the way radio signals from the spacecraft change as they are sent through objects, such as Titan's atmosphere or Saturn's rings, or even behind the Sun. The RSS also studies the compositions, pressures and temperatures of atmospheres and ionospheres, radial structure and particle size distribution within rings, body and system masses and gravitational waves. The instrument uses the spacecraft X-band communication link as well as S-band downlink and Ka-band uplink and downlink.[3]

- Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS)

- The UVIS is a remote sensing instrument that captures images of the ultraviolet light reflected off an object, such as the clouds of Saturn and/or its rings, to learn more about their structure and composition. Designed to measure ultraviolet light over wavelengths from 55.8 to 190 nm, this instrument is also a valuable tool to help determine the composition, distribution, aerosol particle content and temperatures of their atmospheres. Unlike other types of spectrometer, this sensitive instrument can take both spectral and spatial readings. It is particularly adept at determining the composition of gases. Spatial observations take a wide-by-narrow view, only one pixel tall and 64 pixels across. The spectral dimension is 1,024 pixels per spatial pixel. Also, it can take many images that create movies of the ways in which this material is moved around by other forces.[3]

- Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS)

- The VIMS is a remote sensing instrument that captures images using visible and infrared light to learn more about the composition of moon surfaces, the rings, and the atmospheres of Saturn and Titan. It is made up of two cameras in one: one used to measure visible light, the other infrared. VIMS measures reflected and emitted radiation from atmospheres, rings and surfaces over wavelengths from 350 to 5100 nm, to help determine their compositions, temperatures and structures. It also observes the sunlight and starlight that passes through the rings to learn more about their structure. Scientists plan to use VIMS for long-term studies of cloud movement and morphology in the Saturn system, to determine Saturn's weather patterns.[3]

Plutonium power source

Because of Saturn's distance from the sun, solar arrays were not feasible as power sources for this space probe.[10] To generate enough power, such arrays would have been too large and too heavy.[10] Instead, the Cassini orbiter is powered by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which use heat from the natural decay of plutonium-238 (in the form of plutonium dioxide) to generate direct current electricity via thermocouples.[10] The RTGs on the Cassini mission have the same design as those used on the Galileo and Ulysses space probes, and they were designed to have very long operational lifetimes.[10] At the end of the nominal 11-year Cassini mission, they will still be able to produce 600 to 700 watts of electrical power.[10] (One of the spare RTGs for the Cassini mission was used to power the New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper belt, which was designed and launched later on.)

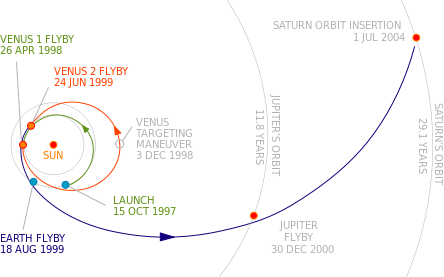

To gain interplanetary momentum while already in flight, the trajectory of the Cassini mission included several gravitational slingshot maneuvers: two fly-by passes of Venus, one more of the Earth, and then one of the planet Jupiter. The terrestrial fly-by was the final instance when the Cassini space probe posed any conceivable danger to human beings. This occurred successfully, with hundreds of miles to spare, on August 18, 1999. Had there been any malfunction that caused the Cassini space probe to collide with the Earth, NASA's complete environmental impact study estimated that, in the worst case (with an acute angle of entry in which Cassini would gradually burn up), a significant fraction of the plutonium-238 inside the RTGs would have been dispersed into the Earth's atmosphere, but the odds against that happening were nearly ten million to one.[11]

At the end of the mission, if NASA decides to crash Cassini into one of Saturn's moons, they will probably choose one of the smaller rocky moons. The heat and radioactivity from its RTG power source would cause melting on an icy moon, which could lead to contamination of the moon by organisms from Earth.[12]

Huygens probe

The Huygens probe, supplied by the European Space Agency (ESA) and named after the 17th century Dutch astronomer who first discovered Titan, Christiaan Huygens, scrutinized the clouds, atmosphere, and surface of Saturn's moon Titan in its descent on January 15, 2005. It was designed to enter and brake in Titan's atmosphere and parachute a fully instrumented robotic laboratory down to the surface.[13]

The probe system consisted of the probe itself which descended to Titan, and the probe support equipment (PSE) which remained attached to the orbiting spacecraft. The PSE includes electronics that track the probe, recover the data gathered during its descent, and process and deliver the data to the orbiter that transmits it to Earth. The data was transmitted by a radio link between Huygens and Cassini provided by Probe Data Relay Subsystem (PDRS). As the probe's mission could not be telecommanded from Earth because of the great distance, it was automatically managed by the Command Data Management Subsystem (CDMS). The PDRS and CDMS were provided by the Italian Space Agency (ASI).

Important events and discoveries

Venus and Earth fly-bys and the cruise to Jupiter

The Cassini space probe performed two gravitational-assist fly-bys of Venus on April 26, 1998, and June 24, 1999. These fly-bys provided the space probe with enough momentum to travel all the way out to the asteroid belt. At that point, the sun's gravity pulled the space probe back into the inner solar system, where it made a gravitational-assist fly-by of the Earth.

On August 18, 1999, at 03:28 UTC, the Cassini craft made a gravitational-assist flyby of the Earth. One hour and 20 minutes before closest approach, Cassini made the closest approach to the Earth's Moon at 377,000 kilometers, and it took a series of calibration photos.

On Jan. 23, 2000, the Cassini space probe performed a fly-by of the asteroid 2685 Masursky at around 10:00 UTC. The Cassini craft took photos[14] in the period five to seven hours before the fly-by at a distance of 1.6 million kilometers, and a diameter of 15 to 20 km. was estimated for the asteroid.

Jupiter flyby

Cassini made its closest approach to Jupiter on December 30, 2000, and made many scientific measurements. About 26,000 images of Jupiter were taken during the months-long flyby. It produced the most detailed global color portrait of Jupiter yet (see image at right), in which the smallest visible features are approximately 60 km (40 miles) across.[15]

The New Horizons mission to Pluto captured more recent images of Jupiter, with a closest approach on February 28, 2007.

A major finding of the flyby, announced on March 6, 2003, was of Jupiter's atmospheric circulation.[16] Dark "belts" alternate with light "zones" in the atmosphere, and scientists had long considered the zones, with their pale clouds, to be areas of upwelling air, partly because many clouds on Earth form where air is rising. But analysis of Cassini imagery showed that individual storm cells of upwelling bright-white clouds, too small to see from Earth, pop up almost without exception in the dark belts. According to Anthony Del Genio of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, "the belts must be the areas of net-rising atmospheric motion on Jupiter, [so] the net motion in the zones has to be sinking."

Other atmospheric observations included a swirling dark oval of high atmospheric-haze, about the size of the Great Red Spot, near Jupiter's north pole. Infrared imagery revealed aspects of circulation near the poles, with bands of globe-encircling winds, with adjacent bands moving in opposite directions.

The same announcement also discussed the nature of Jupiter's rings. Light scattering by particles in the rings showed the particles were irregularly shaped (rather than spherical) and likely originate as ejecta from micrometeorite impacts on Jupiter's moons, probably Metis and Adrastea.

Tests of Einstein's Theory of General Relativity

On October 10, 2003, the Cassini science team announced the results of tests of Einstein's Theory of General Relativity, which were done by using radio waves that were transmitted from the Cassini space probe.[17]

The radio scientists measured a frequency shift in the radio waves to and from the spacecraft, while those signals traveled close to the sun. According to the Theory of General Relativity, a massive object like the sun causes space-time to curve, and a beam of radio waves (or light, or any form of electromagnetic radiation) that passes by the sun has to travel farther because of the curvature.

The extra distance that the radio waves traveled from the Cassini craft, past the sun, to the Earth delays their arrival. The amount of this time delay provides a sensitive test of the calculated predictions of Einstein's Relativity Theory.

Although some measurable deviations from the values that are calculated using the General Theory of Relativity are predicted by some unusual cosmological models, none of these deviations were found by this experiment. Previous tests using radio waves that were transmitted by the Viking and Voyager space probes were in agreement with the calculated values from General Relativity to within an accuracy of one part in one thousand. The more refined measurements from the Cassini space probe experiment improved this accuracy to about one part in 50,000, with the measured data firmly supporting Einstein's General Theory of Relativity.

New moons of Saturn

Using images taken by Cassini, three new moons of Saturn were discovered in 2004. They are very small and were given the provisional names S/2004 S 1, S/2004 S 2 and S/2004 S 5 before being named Methone, Pallene and Polydeuces at the beginning of 2005.

On May 1, 2005, a new moon was discovered by Cassini in the Keeler gap. It was given the designation S/2005 S 1 before being named Daphnis. The only other known moon inside Saturn's ring system is Pan.

A press release on February 3, 2009 shows yet the 6th new moon found by the Cassini Spacecraft. The moon is approximately 1/3 of a mile long in the G-ring of the ring system of Saturn, now named Aegaeon.[18]

A press release on November 2, 2009 mentions the 7th new moon found by the Cassini Spacecraft on July 26, 2009. It is presently labeled S/2009 S 1 and is approximately 300 m (984 ft.) in diameter in the B-ring system.[19]

Phoebe flyby

On June 11, 2004, Cassini flew by the moon Phoebe. This was the first opportunity for close-up studies of this moon since the Voyager 2 flyby. It also was Cassini's only possible flyby for Phoebe due to the mechanics of the available orbits around Saturn.[20]

First close-up images were received on June 12, 2004, and mission scientists immediately realized that the surface of Phoebe looks different from asteroids visited by spacecraft. Parts of the heavily cratered surfaces look very bright in those pictures, and it is currently believed that a large amount of water ice exists under its immediate surface.

Saturn rotation

In an announcement on June 28, 2004, Cassini program scientists described the measurement of the rotational period of Saturn.[21] Since there are no fixed features on the surface that can be used to obtain this period, the repetition of radio emissions was used. These new data agree with the latest values measured from Earth, and constitute a puzzle to the scientists. It turns out that the radio rotational period has changed since it was first measured in 1980 by Voyager, and that it is now 6 minutes longer. This does not indicate a change in the overall spin of the planet, but is thought to be due to movement of the source of the radio emissions to a different latitude, at which the rotation rate is different.

Orbiting Saturn

On July 1, 2004, the spacecraft flew through the gap between the F and G rings and achieved orbit, after a seven year voyage.[22] It is the first spacecraft to ever orbit Saturn.

The Saturn Orbital Insertion (SOI) maneuver performed by Cassini was complex, requiring the craft to orient its High-Gain Antenna away from Earth and along its flight path, to shield its instruments from particles in Saturn's rings. Once the craft crossed the ring plane, it had to rotate again to point its engine along its flight path, and then the engine fired to decelerate the craft by 622 meters per second[23] to allow Saturn to capture it. Cassini was captured by Saturn's gravity at around 8:54 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time on June 30, 2004. During the maneuver Cassini passed within 20,000 km (13,000 miles) of Saturn's cloud tops.

Titan flybys

Cassini had its first distant flyby of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, on July 2, 2004, only a day after orbit insertion, when it approached to within 339,000 km (211,000 mi) of Titan and provided the best look at the moon's surface to date. Images taken through special filters (able to see through the moon's global haze) showed south polar clouds thought to be composed of methane and surface features with widely differing brightness. On October 27, 2004, the spacecraft executed the first of the 45 planned close flybys of Titan when it flew a mere 1,200 kilometers above the moon. Almost four gigabits of data were collected and transmitted to Earth, including the first radar images of the moon's haze-enshrouded surface. It revealed the surface of Titan (at least the area covered by radar) to be relatively level, with topography reaching no more than about 50 meters in altitude. The flyby provided a remarkable increase in imaging resolution over previous coverage. Images with up to 100 times better "resolution" were taken and are typical of resolutions planned for subsequent Titan flybys. (Note that "resolution" refers to the clarity and precision of pictures, and that it has nothing to do with the overall size of the pictures in square centimeters, as is very commonly erroneously stated.)

Huygens' encounter with Titan

Cassini released the Huygens probe on December 25, 2004, by means of a spring. It entered the atmosphere of Titan on January 14, 2005, and after a two-and-a-half-hour descent landed on solid ground with no liquids in view. Although Cassini successfully relayed 350 of the pictures that it received from Huygens of its descent and landing site, a software error failed to turn on one of the Cassini receivers and caused the loss of the other 350 pictures.

Enceladus flybys

During the first two close flybys of the moon Enceladus in 2005, Cassini discovered a "deflection" in the local magnetic field that is characteristic for the existence of a thin but significant atmosphere. Other measurements obtained at that time point to ionized water vapor as being its main constituent. Cassini also observed water ice geysers erupting from the south pole of Enceladus, which gives more credibility to the idea that Enceladus is supplying the particles of Saturn's E ring. Mission scientists hypothesize that there may be pockets of liquid water near the surface of the moon that fuel the eruptions, making Enceladus one of the few bodies in our solar system to contain liquid water.[24]

On March 12, 2008, Cassini made a close fly-by of Enceladus, getting within 50 km of the moon's surface.[25] The spacecraft passed through the plumes extending from its southern geysers, detecting water, carbon dioxide and various hydrocarbons with its mass spectrometer, while also mapping surface features that are at much higher temperature than their surroundings with the infrared spectrometer.[26] Cassini was unable to collect data with its cosmic dust analyzer due to an unknown software malfunction.

On November 21 Cassini again made a fly by of Enceladus,[27] this time with a very different geometry, approaching within 1,600 kilometers (1000 miles) of the surface. The Composit Infrared Spectrograph (CIRS) instrument will make a map of thermal emissions from the tiger stripe Baghdad Sulcus. This is the eighth flyby of Enceladus and is also sometimes referred to as “E-8.” The data and images returned will help to create the most-detailed-yet mosaic image of the southern part of the moon's Saturn-facing hemisphere and a contiguous thermal map of one of the intriguing "tiger stripe" features, with the highest resolution to date.

Radio occultations of Saturn's rings

In May 2005, Cassini began a series of occultation experiments, to measure the size-distribution of particles in Saturn's rings, and measure the atmosphere of Saturn itself. For over 4 months, Cassini completed orbits designed for this purpose. During these experiments, Cassini flew behind the ring plane of Saturn, as seen from Earth, and transmitted radio waves through the particles. The radio signals were received on Earth, where the frequency, phase, and power of the signal was analyzed to help determine the structure of the rings.

Spoke phenomenon verified

In images captured September 5, 2005, Cassini finally detected spokes in Saturn's rings, hitherto seen only by the visual observer Stephen James O'Meara in 1977 and then confirmed by the Voyager space probes in the early 1980s.[28] The exact cause of the spokes is not yet understood. Some hypothetical models predicted that the spokes would not be visible again until 2007.

Lakes of Titan

Radar images obtained on July 21, 2006 appear to show lakes of liquid hydrocarbon (such as methane and ethane) in Titan's northern latitudes. This is the first discovery of currently-existing lakes anywhere besides Earth. The lakes range in size from about a kilometer to one which is one hundred kilometers across.[29]

On March 13, 2007, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory announced that it found strong evidence of seas of methane and ethane in the northern hemisphere of Titan. At least one of these is larger than any of the Great Lakes in North America.[30]

Saturn hurricane

In November 2006, scientists discovered a storm at the south pole of Saturn with a distinct eyewall. This is characteristic of a hurricane on Earth and had never been seen on another planet before. Unlike a terran hurricane, the storm appears to be stationary at the pole. The storm is 8,000 kilometers (5,000 mi) across, and 70 kilometres (43 mi) high, with winds blowing at 560 kilometers per hour (350 mph).[31]

Iapetus flyby

On September 10, 2007, Cassini completed its flyby of the strange, two-toned, walnut-shaped moon, Iapetus. Images were taken from 1,000 miles (1,600 km) above the surface. As it was sending the images back to Earth, it was hit by a cosmic ray which forced it to temporarily enter safe mode. All of the data from the flyby was recovered.[32]

Mission extension

On April 15, 2008, Cassini received funding for a two-year extended mission. It consists of 60 more orbits of Saturn, and includes 21 more Titan flybys, seven of Enceladus, six of Mimas, eight of Tethys, and one targeted flyby each of Dione, Rhea, and Helene.[33] The extended mission began on July 1, 2008, and has since been renamed the Cassini Equinox Mission as the mission coincides with Saturn's equinox.[34] A proposal was submitted to NASA for a second mission extension, provisionally named the extended-extended mission or XXM.[35] This was subsequently approved and renamed the Cassini Solstice Mission.[36] It will see Cassini orbiting Saturn 155 more times, conducting 54 additional flybys of Titan and 11 more of Enceladus. The mission will end with a fiery plunge into the Saturn atmosphere around its 2017 northern summer solstice, safely disposing of the spacecraft without risk of biocontamination to the Saturnian moons.

Trajectory

The initial gravitational-assist trajectory of Cassini–Huygens is the process whereby an insignificant mass approaches a significant mass "from behind" and "steals" some of its orbital momentum. The significant mass, usually a planet, loses a very small proportion of its orbital momentum to the insignificant mass, the space probe in this case. However, due to the space probe's small mass, this momentum transfer gives it a relatively large momentum increase in proportion to its initial momentum, speeding up its travel through outer space.

The Cassini–Huygens space probe performed two gravitational assist fly-bys at Venus, one more fly-by at the Earth, and a final fly-by at Jupiter.

.jpg)

Glossary

- AACS: Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem

- ACS: Attitude Control Subsystem

- AFC: AACS Flight Computer

- ARWM: Articulated Reaction Wheel Mechanism

- ASI: Agenzia Spaziale Italiana, the Italian space agency

- BIU: bus interface unit

- CAM: Command Approval Meeting

- CDS: Command and Data Subsystem—Cassini computer that commands and collects data from the instruments

- CICLOPS: Cassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations

- CIMS: Cassini Information Management System

- DCSS: Descent Control Subsystem

- DSCC: Deep Space Communications Center

- DSN: Deep Space Network (large antennas around the earth)

- DTSTART: Dead Time Start

- ELS: Electron Spectrometer (part of CAPS instrument)

- ERT: Earth-received time, UTC of an event

- ESA: European Space Agency

- ESOC: European Space Operations Centre

- FSW: flight software

- HGA: High Gain Antenna

- HMCS: Huygens Monitoring and Control System

- HPOC: Huygens Probe Operations Center

- IBS: Ion Beam Spectrometer (part of CAPS instrument)

- IEB: Instrument Expanded Blocks (instrument command sequences)

- IMS: Ion Mass Spectrometer (part of CAPS instrument)

- ITL: Integrated Test Laboratory—spacecraft simulator

- IVP: Inertial Vector Propagator

- LGA: Low Gain Antenna

- NAC: Narrow Angle Camera

- NASA: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the United States of America space agency

- OTM: Orbit Trim Maneuver

- PDRS: Probe Data Relay Subsystem

- PHSS: Probe Harness SubSystem

- POSW: Probe On-Board Software

- PPS: Power and Pyrotechnic Subsystem

- PRA: Probe Relay Antenna

- PSA: Probe Support Avionics

- PSIV: Preliminary Sequence Integration and Validation

- PSE: probe support equipment

- RCS: Reaction Control System

- RFS: Radio Frequency Subsystem

- RPX: ring plane crossing

- RWA: Reaction Wheel Assembly

- SCET: Spacecraft Event Time

- SCR: sequence change requests

- SKR: Saturn Kilometric Radiation

- SOI: Saturn Orbit Insertion (July 1, 2004)

- SOP: Science Operations Plan

- SSPS: Solid State Power Switch

- SSR: Solid State Recorder

- SSUP: Science and Sequence Update Process

- TLA: Thermal Louver Assemblies

- USO: UltraStable Oscillator

- VRHU: Variable Radioisotope Heater Units

- WAC: Wide Angle Camera

See also

- Europlanet

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "NASA extends Saturn mission - CNN.com". http://www.cnn.com/2008/TECH/science/04/16/NASA.Saturn.ap/index.html.

- ↑ space.com, Cassini Saturn Probe Gets 7-Year Life Extension, 03 February 2010

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Cassini Orbiter Instruments

- ↑ CAPS team page

- ↑ Waite J. H., Lewis S., Kasprzak W. T., Anicich V. G., Block B. P., Cravens T. E., Fletcher G. G., Ip W. H., Luhmann J. G., McNutt R. L., Niemann H. B., Parejko J. K., Richards J. E., Thorpe R. L., Walter E. M., Yelle R. V. (2004). "The Cassini ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) investigation". Space Science Reviews 114: 113–231. doi:10.1007/s11214-004-1408-2.

- ↑ INMS team page

- ↑ Porco C. C., West R. A., Squyres S., McEwen A., Thomas P., Murray C. D., Delgenio A., Ingersoll A. P., Johnson T. V., Neukum G., Veverka J., Dones L., Brahic A., Burns J. A., Haemmerle V., Knowles B., Dawson D., Roatsch T., Beurle K., Owen W. (2004). "Cassini Imaging Science: Instrument characteristics and anticipated scientific investigations at Saturn". Space Science Reviews 115: 363–497. doi:10.1007/s11214-004-1456-7.

- ↑ Dougherty M. K., Kellock S., Southwood D. J., Balogh A., Smith E. J., Tsurutani B. T., Gerlach B., Glassmeier K. H., Gleim F., Russell C. T., Erdos G., Neubauer E. M., Cowley S. W. H. (2004). "The Cassini magnetic field investigation". Space Science Reviews 114: 331–383. doi:10.1007/s11214-004-1432-2.

- ↑ Krimigis S. M., Mitchell D. G., Hamilton D. C., Livi S., Dandouras J., Jaskulek S., Armstrong T. P., Boldt J. D., Cheng A. F., Gloeckler G., Hayes J. R., Hsieh K. C., Ip W. H., Keath E. P., Kirsch E., Krupp N., Lanzerotti L. J., Lundgren R., Mauk B. H., McEntire R. W., Roelof E. C., Schlemm C. E., Tossman B. E., Wilken B., Williams D. J. (2004). "Magnetosphere imaging instrument (MIMI) on the Cassini mission to Saturn/Titan". Space Science Reviews 114: 233–329. doi:10.1007/s11214-004-1410-8.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "Why the Cassini Mission Cannot Use Solar Arrays". NASA/JPL. 1996-12-06. http://cassini-huygens.jpl.nasa.gov/spacecraft/safety/solar.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ↑ Cassini-Huygens: Spacecraft-Safety

- ↑ "Death of a Spacecraft: The Unknown Fate of Cassini". SPACE.com. November 8, 2006. http://www.space.com/businesstechnology/061108_cassini_fate.html. Retrieved 2007-08-06. ""The issue is the heat that would be generated by the RTGs and the environment that would be created (melted ice) that could be conducive to the viability of any Earth organisms that might have survived on the spacecraft to that point," says Mitchell."

- ↑ http://www.ingenia.org.uk/ingenia/articles.aspx?Index=317 How to Land on Titan, Ingenia, June 2005

- ↑ JPL (February 11, 2000). "New Cassini Images of Asteroid Available". Press release. http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/press-releases-00/20000211-ia-a.cfm. Retrieved 2006-10-14.

- ↑ Hansen C. J., Bolton S. J., Matson D. L., Spilker L. J., Lebreton J. P. (2004). "The Cassini–Huygens flyby of Jupiter". ICARUS 172: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.06.018.

- ↑ Cassini-Huygens: News-Press Releases-2003

- ↑ Bertotti B., Iess L., Tortora P. (2003). "A test of general relativity using radio links with the Cassini spacecraft". Nature 425: 374–376. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v425/n6956/full/nature01997.html.

- ↑ MSN.com

- ↑ IAU Circular No. 9091 (November 2, 2009)

- ↑ Porco C. C., Baker E., Barbara J., Beurle K., Brahic A., Burns J. A., Charnoz S., Cooper N., Dawson D. D., Del Genio A. D., Denk T., Dones L., Dyudina U., Evans M. W., Giese B., Grazier K., Heifenstein P., Ingersoll A. P., Jacobson R. A., Johnson T. V., McEwen A., Murray C. D., Neukum G., Owen W. M., Perry J., Roatsch T., Spitale J., Squyres S., Thomas P. C., Tiscareno M., Turtle E., Vasavada A. R., Veverka J., Wagner R., West R. (2005). "Cassini Imaging Science: Initial results on Phoebe and Iapetus". Science 307 (5713): 1237–1242. doi:10.1126/science.1107981. PMID 15731440.

- ↑ JPL.NASA.GOV: News Releases

- ↑ Porco, Carolyn C. (2007). "Cassini, the first one thousand days". American Scientist 95 (4): 334–341

- ↑ http://trs-new.jpl.nasa.gov/dspace/bitstream/2014/10563/1/02-2613.pdf

- ↑ Cassini-Huygens: News

- ↑ Cassini Spacecraft to Dive Into Water Plume of Saturn Moon NASA.gov, March 10, 2008

- ↑ Cassini Tastes Organic Material at Saturn's Geyser Moon NASA.gov, March 26, 2008

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Catalog Page for PIA05380

- ↑ Cassini-Huygens: News

- ↑ Cassini-Huygens: News

- ↑ "Huge 'hurricane' rages on Saturn". BBC News. November 10, 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6135450.stm. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ "Cassini Probe Flies by Iapetus, Goes Into Safe Mode". Fox News. September 14, 2007. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,296726,00.html.

- ↑ "Cassini’s Tour of the Saturn System". Planetary Society accessdate=2009-02-26. http://www.planetary.org/explore/topics/cassini_huygens/tour.html#xm.

- ↑ "Cassini To Earth: 'Mission Accomplished, But New Questions Await!'". Science Daily. 2008-06-29. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/06/080628223103.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ↑ Cassini's proposed extended-extended mission tour

- ↑ NASA Extends Cassini's Tour of Saturn, Continuing International Cooperation for World Class Science

Further reading

- David M. Harland (2002). Mission to Saturn: Cassini and the Huygens Probe. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 1-85233-656-0.

- Ralph Lorenz and Jacqueline Mitton (2002). Lifting Titan's Veil: Exploring the Giant Moon of Saturn. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79348-3.

- Karl Grossman (1997). The Wrong Stuff: The Space Program's Nuclear Threat to Our Planet. Common Courage Press. ISBN 1-56751-125-2.

External links

- Cassini-Huygens main page at NASA

- Cassini Mission Homepage by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Cassini-Huygens Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Cassini Imaging Homepage

- CASSIE interactive web-browser-based mission explorer/simulator

- Cassini information by the National Space Science Data Center (NSSDC).

- Photo Gallery - full coverage

- Cassini's Tour de Saturn part A, B, C, D, E, F – descriptions of the 4-year tour of Saturn by Bruce Moomaw

- SpaceflightNow news coverage of the mission

- Countdown to Cancel the Cassini Space Probe by the Baltimore Peace Network in 1997 due to concerns over the use of plutonium

- Spacecraft Cassini is Visiting Saturn!—children's stories explaining the Cassini mission

- Yahoo group for the Cassini Huygens mission

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

_large.jpg)