Cardinality

In mathematics, the cardinality of a set is a measure of the "number of elements of the set". For example, the set A = {2, 4, 6} contains 3 elements, and therefore A has a cardinality of 3. There are two approaches to cardinality – one which compares sets directly using bijections and injections, and another which uses cardinal numbers. [1]

The cardinality of a set A is usually denoted | A |, with a vertical bar on each side; this is the same notation as absolute value and the meaning depends on context. Alternately, the cardinality of a set A may be denoted by  or # A.

or # A.

Contents |

Comparing sets

Case 1: | A | = | B |

- Two sets A and B have the same cardinality if there exists a bijection, that is, an injective and surjective function, from A to B.

- For example, the set E = {0, 2, 4, 6, ...} of non-negative even numbers has the same cardinality as the set N = {0, 1, 2, 3, ...} of natural numbers, since the function f(n) = 2n is a bijection from N to E.

Case 2: | A | ≥ | B |

- A has cardinality greater than or equal to the cardinality of B if there exists an injective function from B into A.

Case 3: | A | > | B |

- A has cardinality strictly greater than the cardinality of B if there is an injective function, but no bijective function, from B to A.

- For example, the set R of all real numbers has cardinality strictly greater than the cardinality of the set N of all natural numbers, because the inclusion map i : N → R is injective, but it can be shown that there does not exist a bijective function from N to R (see Cantor's diagonal argument).

Cardinal numbers

Above, "cardinality" was defined functionally. That is, the "cardinality" of a set was not defined as a specific object itself. However, such an object can be defined as follows.

The relation of having the same cardinality is called equinumerosity, and this is an equivalence relation on the class of all sets. The equivalence class of a set A under this relation then consists of all those sets which have the same cardinality as A. There are two ways to define the "cardinality of a set":

- The cardinality of a set A is defined as its equivalence class under equinumerosity.

- A representative set is designated for each equivalence class. The most common choice is the initial ordinal in that class. This is usually taken as the definition of cardinal number in axiomatic set theory.

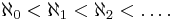

The cardinalities of the infinite sets are denoted

For each ordinal α, ℵα + 1 is the least cardinal number greater than ℵα.

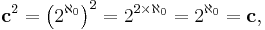

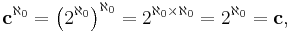

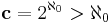

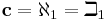

The cardinality of the natural numbers is denoted aleph-null (ℵ0), while the cardinality of the real numbers is denoted by c, and is also referred to as the cardinality of the continuum. We can show that c = 2ℵ0; this also being the cardinality of the set of all subsets of the natural numbers. The continuum hypothesis says that ℵ1 = 2ℵ0, i.e. 2ℵ0 is the smallest cardinal number bigger than ℵ0, i.e. there is no set whose cardinality is strictly between that of the integers and that of the real numbers. The continuum hypothesis still remains unresolved in an "absolute" sense[2]. See below for more details on the cardinality of the continuum.

Finite, countable and uncountable sets

If the axiom of choice holds, the law of trichotomy holds for cardinality. Thus we can make the following definitions:

- Any set X with cardinality less than that of the natural numbers, or | X | < | N |, is said to be a finite set.

- Any set X that has the same cardinality as the set of the natural numbers, or | X | = | N | = ℵ0, is said to be a countably infinite set.

- Any set X with cardinality greater than that of the natural numbers, or | X | > | N |, for example | R | = c > | N |, is said to be uncountable.

Infinite sets

Our intuition gained from finite sets breaks down when dealing with infinite sets. In the late nineteenth century Georg Cantor, Gottlob Frege, Richard Dedekind and others rejected the view of Galileo (which derived from Euclid) that the whole cannot be the same size as the part. One example of this is Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel.

The reason for this is that the various characterizations of what it means for set A to be larger than set B, or to be the same size as set B, which are all equivalent for finite sets, are no longer equivalent for infinite sets. Different characterizations can yield different results. For example, in the popular characterization of size chosen by Cantor, sometimes an infinite set A is larger (in that sense) than an infinite set B; while other characterizations may yield that an infinite set A is always the same size as an infinite set B.

For finite sets, counting is just forming a bijection (i.e., a one-to-one correspondence) between the set being counted and an initial segment of the positive integers. Thus there is no notion equivalent to counting for infinite sets. While counting gives a unique result when applied to a finite set, an infinite set may be placed into a one-to-one correspondence with many different ordinal numbers depending on how one chooses to "count" (order) it.

Additionally, different characterizations of size, when extended to infinite sets, will break different "rules" which held for finite sets. Which rules are broken varies from characterization to characterization. For example, Cantor's characterization, while preserving the rule that sometimes one set is larger than another, breaks the rule that deleting an element makes the set smaller. Another characterization may preserve the rule that deleting an element makes the set smaller, but break another rule. Furthermore, some characterization may not "directly" break a rule, but it may not "directly" uphold it either, in the sense that whichever is the case depends upon a controversial axiom such as the axiom of choice or the continuum hypothesis. Thus there are three possibilities. Each characterization will break some rules, uphold some others, and may be indecisive about some others.

If one extends to multisets, further rules are broken (assuming Cantor's approach), which hold for finite multisets. If we have two multisets A and B, A not being larger than B and B not being larger than A does not necessarily imply A has the same size as B. This rule holds for multisets that are finite. Needless to say, the law of trichotomy is explicitly broken in this case, as opposed to the situation with sets, where it is equivalent to the axiom of choice.

Dedekind simply defined an infinite set as one having the same size (in Cantor's sense) as at least one of its proper parts; this notion of infinity is called Dedekind infinite. This definition only works in the presence of some form of the axiom of choice, however, so will not be considered to work by some mathematicians.

Cantor introduced the above-mentioned cardinal numbers, and showed that (in Cantor's sense) some infinite sets are greater than others. The smallest infinite cardinality is that of the natural numbers (ℵ0).

Cardinality of the continuum

One of Cantor's most important results was that the cardinality of the continuum (c) is greater than that of the natural numbers (ℵ0); that is, there are more real numbers R than whole numbers N. Namely, Cantor showed that

- (see Cantor's diagonal argument).

The continuum hypothesis states that there is no cardinal number between the cardinality of the reals and the cardinality of the natural numbers, that is,

- (see Beth one).

However, this hypothesis can neither be proved nor disproved within the widely accepted ZFC axiomatic set theory, if ZFC is consistent.

Cardinal arithmetic can be used to show not only that the number of points in a real number line is equal to the number of points in any segment of that line, but that this is equal to the number of points on a plane and, indeed, in any finite-dimensional space. These results are highly counterintuitive, because they imply that there exist proper subsets and proper supersets of an infinite set S that have the same size as S, although S contains elements that do not belong to its subsets, and the supersets of S contain elements that are not included in it.

The first of these results is apparent by considering, for instance, the tangent function, which provides a one-to-one correspondence between the interval (−½π, ½π) and R (see also Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel).

The second result was first demonstrated by Cantor in 1878, but it became more apparent in 1890, when Giuseppe Peano introduced the space-filling curves, curved lines that twist and turn enough to fill the whole of any square, or cube, or hypercube, or finite-dimensional space. These curves are not a direct proof that a line has the same number of points as a finite-dimensional space, but they can be easily used to obtain such a proof.

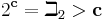

Cantor also showed that sets with cardinality strictly greater than  exist (see his generalized diagonal argument and theorem). They include, for instance:

exist (see his generalized diagonal argument and theorem). They include, for instance:

-

- the set of all subsets of R, i.e., the power set of R, written P(R) or 2R

- the set RR of all functions from R to R

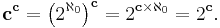

Both have cardinality

- (see Beth two).

The cardinal equalities

and

and  can be demonstrated using cardinal arithmetic:

can be demonstrated using cardinal arithmetic:

Examples and properties

- If X = {a, b, c} and Y = {apples, oranges, peaches}, then | X | = | Y | because {(a, apples), (b, oranges), (c, peaches)} is a bijection between the sets X and Y. The cardinality of each of X and Y is 3.

- If | X | < | Y |, then there exists Z such that | X | = | Z | and Z ⊆ Y.

- Sets with cardinality c

See also

- Aleph number

- Beth number

- Ordinality

- Countable set

References

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Cardinal Number." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CardinalNumber.html

- ↑ Penrose, R (2005), The Road to Reality: A Complete guide to the Laws of the Universe, Vintage Books, ISBN 0-099-44068-7