Cajun

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-5 million | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cajun French |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Predominantly Roman Catholic |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

Cajuns (pronounced /ˈkeɪdʒən/; French: les Cadiens or les Acadiens, [le kadjɛ̃, le zakadjɛ̃]) are an ethnic group mainly living in Louisiana, consisting of the descendants of Acadian exiles (French-speaking settlers from Acadia in what are now the maritime provinces of Canada - New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, or Prince Edward Island). Today, the Cajuns make up a significant portion of south Louisiana's population, and have exerted an enormous impact on the state's culture.[1]

Acadia consisted mainly of present-day Nova Scotia, and included parts of eastern Quebec, the other Maritime provinces, and modern-day Maine. The origin of the designation Acadia is credited to the explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano, who on his sixteenth century map applied the ancient Greek name "Arcadia" to the entire Atlantic coast north of Virginia. "Arcadia" derives from the Arcadia district in Greece which since Classical antiquity had the extended meanings of "refuge" or "idyllic place". The Dictionary of Canadian Biography says: "In the 17th century Champlain fixed its present orthography, with the 'r' omitted, and (the Canadian historian) W.F.Ganong has shown its gradual progress northwards, in a succession of maps, to its resting place in the Atlantic Provinces."[2]

Contents |

Ethnic group of national origin

The Cajuns retain a unique dialect of the French language and numerous other cultural traits that distinguish them as an ethnic group. Cajuns were officially recognized by the U.S. government as a national ethnic group in 1980 per a discrimination lawsuit filed in federal district court. Presided over by Judge Edwin Hunter, the case, known as Roach v. Dresser Industries Valve and Instrument Division (494 F.Supp. 215, D.C. La., 1980), hinged on the issue of the Cajuns' ethnicity. Significantly, Judge Hunter held in his ruling that:

| “ | We conclude that plaintiff is protected by Title VII's ban on national origin discrimination. The Louisiana Acadian (Cajun) is alive and well. He is 'up front' and 'main stream.' He is not asking for any special treatment. By affording coverage under the 'national origin' clause of Title VII he is afforded no special privilege. He is given only the same protection as those with English, Spanish, French, Iranian, Portuguese, Mexican, Italian, Irish, et al., ancestors. | ” |

|

—- Judge Edwin Hunter 1980. |

||

History of Acadian ancestors

The British evicted the Acadians from Acadia (which has since been resettled and consists of parts of present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, Canada) in the period 1755-1763. This has become known as the Great Upheaval or Le Grand Dérangement. At the time there was a war between France and Great Britain over the colony of New France. This war is known in the United States as the French and Indian War; it was one theater of the Seven Years' War that was fought chiefly in Europe.

The Acadians' migration from Canada and the Thirteen Colonies was spurred by the Treaty of Paris (1763) which ended the war. The treaty terms provided 18 months for unrestrained emigration. Many Acadians moved to the region of the Atakapa, often travelling via the French Colony of Saint-Domingue (present day Haiti).[3] Joseph Broussard led the first group 200 of Acadians to arrive in Louisiana on February 27, 1765 aboard the Santo Domingo.[4] On April 8, 1765, he was appointed militia captain and commander of the "Acadians of the Atakapas" region in St. Martinville, La.[5] Some of the settlers wrote poignant letters to their family scattered around the Atlantic to encourage them to join them at New Orleans. For example, Jean-Baptiste Semer, wrote to his father in France:

| “ | My dear father (...) you can come here boldly with my dear mother and all the other Acadian families. They will always be better off than in France. There are neither duties nor taxes to pay and the more one works, the more one earns without doing harm to anyone | ” |

|

—- Jean-Baptiste Semer 1766[6] |

||

Only after many of the Cajuns had moved to Louisiana, seeking to live under a French government, did they discover France had secretly ceded Louisiana to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762). The formal announcement of the transfer was made in December 1764. The Cajuns took part in the Rebellion of 1768 in an attempt to prevent the transfer. The Spanish formally asserted control in 1769.

The Acadians were scattered throughout the eastern seaboard. Families were split and put on ships with different destinations[7]. Many ended up west of the Mississippi River in what was then French-colonized Louisiana, including territory as far north as Dakota territory. France had ceded the colony to Spain in 1762, prior to their defeat by Britain and two years before the first Acadians began settling in Louisiana. The interim French officials provided land and supplies to the new settlers. The Spanish governor, Bernardo de Gálvez, later proved to be hospitable, permitting the Acadians to continue to speak their language, practice their native religion, Roman Catholicism—which was also the official religion of Spain—and otherwise pursue their livelihoods with minimal interference. Some families and individuals did travel north through the Louisiana territory to set up homes as far north as Wisconsin. Cajuns fought in the American Revolution. Although they fought for Spanish General Galvez, their contribution to the winning of the war has been recognized.[8]

"Galvez leaves New Orleans with an army of Spanish regulars and the Louisiana militia made up of 600 Cajun volunteers and captures the British strongholds of Fort Bute at Bayou Manchac, across from the Acadian settlement at St. Gabriel. And on September 21, they attack and capture Baton Rouge."

A review of the list of members shows many common Cajun names among soldiers who participated in the Battle of Baton Rouge and the Battle for West Florida. The Galvez Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution was formed in memory of those soldiers.[9] The Acadians' joining the fight against the British was partially a reaction to the British evicting them from Acadia.

The Spanish colonial government settled the earliest group of Acadian exiles west of New Orleans, in what is now south-central Louisiana—an area known at the time as Attakapas, and later the center of the Acadiana region. As Brasseaux wrote, "The oldest of the pioneer communities . . . Fausse Point, was established near present-day Loreauville by late June, 1765."[10] The Acadians shared the swamps, bayous and prairies with the Attakapa and Chitimacha Native American tribes.

After the end of American Revolutionary War, about 1,500 more Acadians arrived in New Orleans. About 3,000 Acadians had been deported to France during the Great Upheaval. In 1785 about 1,500 of them obtained the authorisation to emigrate to Louisiana, often to be reunited with their families or because they could not settle in France.[11] Mostly secluded until the early 1900s, Cajuns today are largely assimilated into the mainstream society and culture. Some Cajuns live in communities outside of Louisiana. Also, some people identify themselves as Cajun culturally despite lacking Acadian ancestry.

Ethnic mixing and alternate origins

Not all Cajuns descend solely from Acadian exiles who settled in south Louisiana in the eighteenth century, as many have intermarried with other groups. Their members now include people with ancestry of British, Spanish, German, Italian, Native American, Métis and French Creole settlers. Historian Carl A. Brasseaux asserted that it was this process of intermarriage that created the Cajuns in the first place.[1]

Non-Acadian French Creoles in rural areas were absorbed into Cajun communities. Some Cajun parishes, such as Evangeline and Avoyelles, possess relatively few inhabitants of Acadian origin. Their populations descend in many cases from settlers who migrated to the region from Quebec, Mobile, or directly from France. Theirs is regarded as the purest dialect of French spoken within Acadiana. Regardless, it is generally acknowledged that Acadian influences have prevailed in most sections of south Louisiana.

Many Cajuns also have ancestors who were not French. Many of the original settlers in French Acadia were English, for example the Melansons (originally Mallinson). Irish, German, Greek, and Italian colonists began to settle in Louisiana before and after the Louisiana Purchase, particularly on the German Coast along the Mississippi River north of New Orleans. People of Latin American origin, many Spanish people of Canary Islanders descent, a number of early Filipino settlers (notably in Saint Malo) from the cross-Pacific Galleon trade with neighboring Mexico, and descendants of African American slaves and some Cuban Americans, have also settled along the Gulf Coast and, in some cases, intermarried into Cajun families. Anglo-American settlers in the region often were assimilated into Cajun communities, especially those who arrived before the English language became predominant in southern Louisiana.

One obvious result of this cultural mixture is the variety of surnames that are common among the Cajun population. Surnames of the original Acadian settlers (which are documented) have been augmented by French and non-French family names that have become part of Cajun communities. The spelling of many family names has changed over time. (See, for example, Eaux).

Modern preservation and renewed connections

During the early part of the 20th century, attempts were made to suppress Cajun culture by measures such as forbidding the use of the Cajun French language in schools. After the Compulsory Education Act forced Cajun children to attend formal schools, American teachers threatened, punished, and sometimes beat their Cajun students in an attempt to force them to use English (a language many of them had not been exposed to before). During World War II, Cajuns often served as French interpreters for American forces in France; this helped to overcome prejudice.[12]

In 1968 the organization of Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) was founded to preserve the French language in Louisiana. Besides advocating for their legal rights, Cajuns also recovered for themselves a sense of ethnic pride and appreciation for their ancestry. Since the mid-1950s, relations between the Cajuns of the U.S. Gulf Coast and Acadians in the Maritimes and New England have been renewed, forming an Acadian identity common to Louisiana, New England, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

State Senator Dudley LeBlanc ("Coozan Dud", a Cajun slang nickname for "Cousin Dudley") took a group of Cajuns to Nova Scotia in 1955 for the commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the expulsion. The Congrès Mondial Acadien, a large gathering of Acadians and Cajuns held every five years since 1994, is another example of continued unity.

Sociologists Jacques Henry and Carl L. Bankston III have maintained that the preservation of Cajun ethnic identity is a result of the social class of Cajuns. During the eighteenth and nineteenth century, "Cajuns" came to be identified as the French-speaking rural people of Southwestern Louisiana. Over the course of the twentieth century, the descendants of these rural people became the working class of their region. This change in the social and economic circumstances of families in Southwestern Louisiana created nostalgia for an idealized version of the past. Henry and Bankston point out that "Cajun", which was formerly considered an insulting term, became a term of pride among Louisianans by the beginning of the twenty-first century.[13]

Culture

Geography

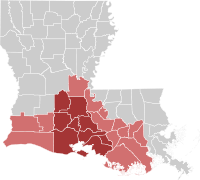

Geography had a strong correlation to Cajun lifestyles. Most Cajuns resided in Acadiana, where their descendants are still predominant. Cajun populations today are found also in the area southwest of New Orleans and scattered in areas adjacent to the French Louisiana region, such as to the north in Alexandria, Louisiana. Over the years, many Cajuns and Creoles also migrated to the Beaumont and Port Arthur area of Southeast Texas, in especially large numbers as they followed oil-related jobs in the 1970s and 1980s, when oil companies moved jobs from Louisiana to Texas. However, the city of Lafayette is referred to as "The Heart of Acadiana" because of its location, and it is a major center of Cajun-Creole culture.

Music

Cajun music is evolved from its roots in the music of the French-speaking Catholics of Canada. In earlier years the fiddle was the predominant instrument, but gradually the accordion has come to share the limelight. Cajun music gained national attention in 2007, when the Grammy Award for Best Zydeco or Cajun Music Album category was created.[14]

Cuisine

Outside Louisiana, and even within, some food writers wish to distinguish between Cajun and Louisiana Creole cuisine, maintaining that Creole dishes tend to be more sophisticated and continental while Cajun food is rural, more seasoned, sometimes spicy, and tends to be heartier. This distinction is based mostly on encounters with the cuisines as encountered in eateries in New Orleans. Outside the city, Cajuns and Creoles often intermingle socially and culturally, and chances are that the cooking of Cajuns and Creoles living in Lawtell, for example, have more in common with each other than the Creole dishes of a Lawtell resident and one from Isle Brevelle. Both cuisines tend to focus on local ingredients like locally available wild game (e.g., duck, rabbit), vegetables (e.g., okra, mirlitons), and grain (e.g., rice), which is where they remain distinctive, since many of these ingredients have never truly entered American mainstream cuisine and thus were available to displace local traditions.

Since many Cajuns and Creoles were farmers and not especially wealthy, they were known for not wasting any part of a butchered animal. Cracklins are a popular snack made by frying pork skins and boudin is created from the ground-up leftover parts of a hog after the best meat is taken, which is mixed with cooked rice. It is usually formed into a sausage, but can also be rolled in a ball and deep-fried.[15]

Language

Cajun French is a variety or dialect of the French language spoken primarily in the Acadiana region of Louisiana. At one time there were as many as seven dialects spread across the Cajun Heartland.

Recent documentation has been made of Cajun English, a French-influenced dialect of English spoken by Cajuns, either as a second language, in the case of the older members of the community, or as a first language by younger Cajuns.

Religious traditions

Cajuns are predominantly Roman Catholic. However, Protestant and Evangelical Christian denominations have made inroads among Cajuns, but not without controversy — many Cajuns will shun family members if they convert to any form of Protestantism because of the extreme persecution the Cajuns were subjected to by Protestants during the Great Expulsion of 1755, and throughout their history for maintaining their Catholicism.

The 1992 cookbook, Who's Your Mama, Are You Catholic and Can You Make a Roux by Cajun Chef Marcelle Bienvenue outlines long-standing beliefs that Cajun identity was rooted in community, cuisine, and very specifically, devout Roman Catholicism. Traditional Catholic religious observances such as Mardi Gras, Lent, and Holy Week are integral to many Cajun communities.

Mardi Gras

Mardi Gras, (French for "Fat Tuesday", also known as Shrove Tuesday), is the day before Ash Wednesday, which marks the beginning of Lent, a 40 day period of fasting and reflection in preparation for Easter Sunday. Mardi Gras was historically a time to use up the foods that were not to be used during Lent, including fat, eggs, and meat.

Mardi Gras celebrations in rural Acadiana are distinct from the more widely known celebrations in New Orleans and other metropolitan areas. One tradition is the wearing of a capuchon, which is a cone-shaped ceremonial hat. Another distinct feature of Cajun celebration centers on the courir (translated: to run). A group of people, usually on horseback, will approach a farmhouse and ask for something for the community gumbo pot. Often, the farmer or his wife will allow the riders to have a chicken, if they can catch it. The group then puts on a show, comically attempting to catch the chicken set out in a large open area. Songs are sung, jokes are told, and skits are acted out. When and if the chicken is caught, it is added to the pot at the end of the day. The Courir de Mardi Gras held in the small town of Mamou has become well known. This tradition has much in common with the observance of La Chandeleur, or Candlemas (February 2), by Acadians in Nova Scotia.

After New Orleans, the city of New Roads in Louisiana has the 2nd oldest Mardi Gras celebration in Louisiana. New Roads is located in Pointe Coupee Parish.

Easter

On Pâques (French for Easter), a game called pâquer, or pâque-pâque was played. Contestants selected hard-boiled eggs, paired off, and tapped the eggs together — the player whose egg did not crack was declared the winner. This is an old European tradition that has survived in Acadia until today. Today Easter is still celebrated by Cajuns with the traditional game of 'paque', but is now also celebrated in the same fashion as Christians throughout the United States with candy-filled baskets, "Easter bunny" stories, dyed eggs, and Easter Egg hunts.

Folk beliefs

One folk custom is belief in a traiteur, or Cajun healer, whose primary method of treatment involves the laying on of hands and of prayers. An important part of Cajun folk religion, the traiteur is a faith healer who combines Catholic prayer and medicinal remedies to treat a variety of ailments, including earaches, toothaches, warts, tumors, angina, and bleeding. Another is in the Rougarou, a version of a Loup Garou (French for werewolf), that will hunt down and kill Catholics that do not follow the rules of Lent. In some Cajun communities the Loup Garou of legend have taken on an almost protective role. Children are warned that Loup Garou can read souls, and that they only hunt and kill evil men and misbehaved horses.

Celebrations and gatherings

Cajuns, along with other Cajun Country residents, have a reputation for a joie de vivre (French for "joy of living"), in which hard work is appreciated as much as "passing a good time."

Community gatherings

In the culture, a coup de main (French for "to give a hand") is an occasion when the community gathers in order to assist one of their members with time-consuming or arduous tasks. Examples might include a barn raising, harvests, or assistance for the elderly or sick.

Festivals

Laissez les bons temps rouler is a more than a cliché phrase of the local culture, which means "let the good times roll", as nearly every village, town and city of any size has a yearly festival, celebrating an important part of the local culture and economy. The majority of Cajun festivals include a fais do-do ("go to sleep" in French) or street dance, usually to a live local band. Crowds at these festivals can range from a few hundred to more than 100,000.

Other festivals outside of Louisiana

- In Texas, the Winnie Rice Festival and other celebrations often highlight the Cajun influence in Southeast Texas.

- Major Cajun/Zydeco festivals are held annually in Rhode Island, which does not have a sizable Cajun population but is home to many Franco-Americans of Québécois and Acadian descent. It features Cajun culture and food, as well as authentic Louisiana musical acts both famous and unknown, drawing attendance not only from the strong Cajun/Zydeco music scene in Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York City and California, but from all over the world. In recent years the festival became so popular that there are now several such large summer festivals near the Connecticut-Rhode Island border: The Great Connecticut Cajun and Zydeco Music & Arts Festival, The Blast From The Bayou Cajun and Zydeco Festival, Rhythm & Roots Festival also in California the Cajun/Zydeco Festival; Bay Area Ardenwood Historic Farm, Fremont, Calif. and The Simi Valley Cajun, Creole Music Festival.

Tributes

Documentary films

- Spend it All (1971, color) director: Les Blank with Skip Gerson

- Hot Pepper (1973, color) director: Les Blank

- J'ai Été Au Bal (English: I Have Been To the Ball), by Les Blank, Chris Strachwitz & Maureen Gosling; narrated by Barry Jean Ancelet and Michael Doucet (Brazos Films). Louisiana French and Zydeco music documentary.

- Louisiana Story (1948, black and white) director: Robert Flaherty. Further addressed in 2006 documentary Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story, by a group at Louisiana State University.

Film

- Southern Comfort (film) (1981, color) director: Walter Hill, starring Powers Boothe

- Belizaire the Cajun (1986, color) director: Glen Pitre, starring Armand Assante

- Little Chenier (2006, color) director: Bethany Ashton, starring Johnathon Schaech

Literature

- Evangeline (1847), an epic poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow loosely based on the events surrounding the 1755 deportation. It became an American classic, and also contributed to a rebirth of Acadian identity in both Maritime Canada and in Louisiana.

- Bayou Folk (1894) by Kate Chopin who wrote about the Creoles and Cajuns (Acadiens).

- Children's book author Mary Alice Fontenot wrote several volumes on Cajun culture and history.

Songs

- Jambalaya (On the Bayou), (1952), a song credited to Hank Williams. Jambalaya is about life, parties and stereotypical food of Cajun cuisine.

- Acadian Driftwood (1975), a popular song based on the Acadian Expulsion by Robbie Robertson that appeared on The Band's album, Northern Lights - Southern Cross.

- Louisiana Man, an autobiographical song written and performed by Doug Kershaw. It became the first song broadcast back to Earth from the Moon by the astronauts of Apollo 12. The song not only sold millions of copies but over the years has become the symbol of Cajun music.

- Jolie Blonde: lyrics & song history of the traditional Cajun waltz (aka Jolie Blon, Jole Blon or Joli Blon) often referred to as "the Cajun National Anthem".

- Mississippi Queen, 1970 song by Mountain about a Cajun woman visiting from Mississippi

- Elvis Presley was a Cajun, a song from the 1991 Irish film The Commitments in which a 2-piece band plays along to the lyric "Elvis was a Cajun, he had a Cajun Heart"

- Amos Moses, a song by Jerry Reed about a fictional one-armed alligator-hunting Cajun man.

See also

- List of Cajuns

- French Canadians

- Great Upheaval

- Cajun cuisine

References

Sources

- Maria Hebert-Leiter "Becoming Cajun, Becoming American: The Acadian in American Literature from Longfellow to James Lee Burke". Baton Rouge,LA. :Louisiana State University Press, 2009 ISBN 978-0-8071-3435-1

- Dean Jobb, The Cajuns: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph, John Wiley & Sons, 2005 (published in Canada as The Acadians: A People's Story of Exile and Triumph)

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carl A. Brasseaux, Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, 2nd edition

- ↑ Link to Dictionnary of Canadian Biography online

- ↑ Gabriel Debien, "The Acadians in Santo-Domingo, 1764-1789" in: Glenn R. Conrad, ed., The Cajuns: Essays on their History and Culture Lafayette, La., 1978, 21-96.

- ↑ www.carencrohighschool.org "Broussard named for early settler Valsin Broussard"

- ↑ "History:1755-Joseph Broussard dit Beausoleil (c. 1702-1765)". http://www2.umoncton.ca/cfdocs/etudacad/1755/index.cfm?id=010505000&lang=en&style=G&admin=false&linking=.

- ↑ "Letter by Jean-Baptiste Semer, an Acadian in New Orleans, to His Father in Le Havre, April 20, 1766." Transl. Bey Grieve. Louisiana History 48 (spring 2007): 219-26 Link to full transcription of the Letter by Jean-Baptist Semer

- ↑ John Mack Faragher (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland, New York: W.W. Norton, 562 pages ISBN 0-393-05135-8 (online excerpt)

- ↑ Acadians who fought in the American Revolution

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Carl A. Brasseaux (1987), The Founding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life in Louisiana, 1765-1803 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987), pp. 91-92.

- ↑ Jean-Francois Mouhot (2009), Les Réfugiés Acadiens en France (1758-1785): L'Impossible Réintégration? Quebec: Septentrion, 456p.

- ↑ Tidwell, Michael. Bayou Farewell:The Rich Life and Tragic Death of Louisiana's Cajun Coast. Vintage Departures: New York, 2004.

- ↑ Blue Collar Bayou

- ↑ Grammy Awards

- ↑ Michael Stern. 500 Things to Eat Before It's Too Late: And the Very Best Places to Eat Them. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. ISBN 0547059078, 9780547059075. http://books.google.com/books?id=uha0mHZ-N8oC&lpg=PA141&ots=D_tqH6GuQC&dq=%22boudin%20ball%22&pg=PA141#v=onepage&q=%22boudin%20ball%22&f=false. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

External links

- "St. Martinville, Louisiana", Acadian Memorial

- "Erath, Louisiana", Acadian Museum

- "Living history museum, Lafayette, Louisiana", Vermilionville Website

- "The Silence of the Gators: Cajun Ethnicity and Intergenerational Transmission of Louisiana French", Multilingual Matters

- Margaret D. Bauer, "An Interview with Tim Gautreaux: 'Cartographer of Louisiana Back Roads'", Southern Spaces, 28 May 2009. http://southernspaces.org/2009/interview-tim-gautreaux-cartographer-louisiana-back-roads

- Chandeleur

- The Simi Valley Cajun, Creole Music Festival

- Jolie Blonde : lyrics & song history

- J'ai Été Au Bal

- Cajun/Zydeco Festival; Bay Area Ardenwood Historic Farm, Fremont, Calif.

- The Great Connecticut Cajun and Zydeco Music & Arts Festival

- Rhythm & Roots Festival

- The Blast From The Bayou Cajun and Zydeco Festival

- Cajun Culture

- Patricia A. Suchy and James V. Catano, "Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story," Southern Spaces, 27 April 2010.

- Charles Reagan Wilson. "Cajun South Louisiana", Southern Spaces, 12 March 2004.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||