Butterfly

| Butterflies | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Charaxes brutus natalensis in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| (unranked): | Rhopalocera |

| Subgroups | |

|

|

A butterfly is a mainly day-flying insect of the order Lepidoptera, the butterflies and moths. Like other holometabolous insects, the butterfly's life cycle consists of four parts, egg, larva, pupa and adult. Most species are diurnal. Butterflies have large, often brightly coloured wings, and conspicuous, fluttering flight. Butterflies comprise the true butterflies (superfamily Papilionoidea), the skippers (superfamily Hesperioidea) and the moth-butterflies (superfamily Hedyloidea). All the many other families within the Lepidoptera are referred to as moths.

Butterflies exhibit polymorphism, mimicry and aposematism. Some, like the Monarch, will migrate over long distances. Some butterflies have evolved symbiotic and parasitic relationships with social insects such as ants. Some species are pests because in their larval stages they can damage domestic crops or trees; however, some species are agents of pollination of some plants, and caterpillars of a few butterflies (e.g., Harvesters) eat harmful insects. Culturally, butterflies are a popular motif in the visual and literary arts.

Contents |

Life cycle

It is a popular belief that butterflies have very short life spans. However, butterflies in their adult stage can live from a week to nearly a year depending on the species. Many species have long larval life stages while others can remain dormant in their pupal or egg stages and thereby survive winters.[1]

Butterflies may have one or more broods per year. The number of generations per year varies from temperate to tropical regions with tropical regions showing a trend towards multivoltinism.

Egg

Butterfly eggs are protected by a hard-ridged outer layer of shell, called the chorion. This is lined with a thin coating of wax which prevents the egg from drying out before the larva has had time to fully develop. Each egg contains a number of tiny funnel-shaped openings at one end, called micropyles; the purpose of these holes is to allow sperm to enter and fertilize the egg. Butterfly and moth eggs vary greatly in size between species, but they are all either spherical or ovate.

Butterfly eggs are fixed to a leaf with a special glue which hardens rapidly. As it hardens it contracts, deforming the shape of the egg. This glue is easily seen surrounding the base of every egg forming a meniscus. The nature of the glue is unknown and is a suitable subject for research. The same glue is produced by a pupa to secure the setae of the cremaster. This glue is so hard that the silk pad, to which the setae are glued, cannot be separated.

Eggs are usually laid on plants. Each species of butterfly has its own hostplant range and while some species of butterfly are restricted to just one species of plant, others use a range of plant species, often including members of a common family.

The egg stage lasts a few weeks in most butterflies but eggs laid close to winter, especially in temperate regions, go through a diapause (resting) stage, and the hatching may take place only in spring. Other butterflies may lay their eggs in the spring and have them hatch in the summer. These butterflies are usually northern species, such as the Mourning Cloak (Camberwell Beauty) and the Large and Small Tortoiseshell butterflies.

Caterpillars

Butterfly larvae, or caterpillars, consume plant leaves and spend practically all of their time in search of food. Although most caterpillars are herbivorous, a few species such as Spalgis epius and Liphyra brassolis are entomophagous (insect eating).

Some larvae, especially those of the Lycaenidae, form mutual associations with ants. They communicate with the ants using vibrations that are transmitted through the substrate as well as using chemical signals.[2][3] The ants provide some degree of protection to these larvae and they in turn gather honeydew secretions.

Caterpillars mature through a series of stages called instars. Near the end of each instar, the larva undergoes a process called apolysis, in which the cuticle, a tough outer layer made of a mixture of chitin and specialized proteins, is released from the softer epidermis beneath, and the epidermis begins to form a new cuticle beneath. At the end of each instar, the larva moults the old cuticle, and the new cuticle expands, before rapidly hardening and developing pigment. Development of butterfly wing patterns begins by the last larval instar.

Butterfly caterpillars have three pairs of true legs from the thoracic segments and up to 6 pairs of prolegs arising from the abdominal segments. These prolegs have rings of tiny hooks called crochets that help them grip the substrate.

Some caterpillars have the ability to inflate parts of their head to appear snake-like. Many have false eye-spots to enhance this effect. Some caterpillars have special structures called osmeteria which are everted to produce smelly chemicals. These are used in defense.

Host plants often have toxic substances in them and caterpillars are able to sequester these substances and retain them into the adult stage. This helps making them unpalatable to birds and other predators. Such unpalatibility is advertised using bright red, orange, black or white warning colours. The toxic chemicals in plants are often evolved specifically to prevent them from being eaten by insects. Insects in turn develop countermeasures or make use of these toxins for their own survival. This "arms race" has led to the coevolution of insects and their host plants.[4]

Wing development

Wings or wing pads are not visible on the outside of the larva, but when larvae are dissected, tiny developing wing disks can be found on the second and third thoracic segments, in place of the spiracles that are apparent on abdominal segments. Wing disks develop in association with a trachea that runs along the base of the wing, and are surrounded by a thin peripodial membrane, which is linked to the outer epidermis of the larva by a tiny duct.

Wing disks are very small until the last larval instar, when they increase dramatically in size, are invaded by branching tracheae from the wing base that precede the formation of the wing veins, and begin to develop patterns associated with several landmarks of the wing.

Near pupation, the wings are forced outside the epidermis under pressure from the hemolymph, and although they are initially quite flexible and fragile, by the time the pupa breaks free of the larval cuticle they have adhered tightly to the outer cuticle of the pupa (in obtect pupae). Within hours, the wings form a cuticle so hard and well-joined to the body that pupae can be picked up and handled without damage to the wings.

Pupa

When the larva is fully grown, hormones such as prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) are produced. At this point the larva stops feeding and begins "wandering" in the quest of a suitable pupation site, often the underside of a leaf.

The larva transforms into a pupa (or chrysalis) by anchoring itself to a substrate and moulting for the last time. The chrysalis is usually incapable of movement, although some species can rapidly move the abdominal segments or produce sounds to scare potential predators.

The pupal transformation into a butterfly through metamorphosis has held great appeal to mankind. To transform from the miniature wings visible on the outside of the pupa into large structures usable for flight, the pupal wings undergo rapid mitosis and absorb a great deal of nutrients. If one wing is surgically removed early on, the other three will grow to a larger size. In the pupa, the wing forms a structure that becomes compressed from top to bottom and pleated from proximal to distal ends as it grows, so that it can rapidly be unfolded to its full adult size. Several boundaries seen in the adult color pattern are marked by changes in the expression of particular transcription factors in the early pupa.

Adult or imago

The adult, sexually mature, stage of the insect is known as the imago. As Lepidoptera, butterflies have four wings that are covered with tiny scales (see photo). The fore and hindwings are not hooked together, permitting a more graceful flight. An adult butterfly has six legs, but in the nymphalids, the first pair is reduced. After it emerges from its pupal stage, a butterfly cannot fly until the wings are unfolded. A newly emerged butterfly needs to spend some time inflating its wings with blood and letting them dry, during which time it is extremely vulnerable to predators. Some butterflies' wings may take up to three hours to dry while others take about one hour. Most butterflies and moths will excrete excess dye after hatching. This fluid may be white, red, orange, or in rare cases, blue.

External morphology

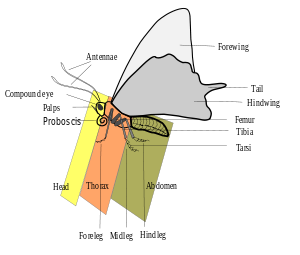

Parts of an adult butterfly |

Butterflies have two antennae, two compound eyes, and a proboscis |

Adult butterflies have four wings: a forewing and hindwing on both the left and the right side of the body. The body is divided into three segments: the head, thorax, and the abdomen. They have two antennae, two compound eyes, and a proboscis.

Scales

Butterflies are characterized by their scale-covered wings. The coloration of butterfly wings is created by minute scales. These scales are pigmented with melanins that give them blacks and browns, but blues, greens, reds and iridescence are usually created not by pigments but the microstructure of the scales. This structural coloration is the result of coherent scattering of light by the photonic crystal nature of the scales.[5][6][7] The scales cling somewhat loosely to the wing and come off easily without harming the butterfly.

Photographic and light microscopic images Zoomed-out view of an Inachis io. Closeup of the scales of the same specimen. High magnification of the coloured scales (probably a different species). Electron microscopic images A patch of wing Scales close up A single scale Microstructure of a scale Magnification Approx. ×50 Approx. ×200 ×1000 ×5000

Polymorphism

Many adult butterflies exhibit polymorphism, showing differences in appearance. These variations include geographic variants and seasonal forms. In addition many species have females in multiple forms, often with mimetic forms. Sexual dimorphism in coloration and appearance is widespread in butterflies. In addition many species show sexual dimorphism in the patterns of ultraviolet reflectivity, while otherwise appearing identical to the unaided human eye. Most of the butterflies have a sex-determination system that is represented as ZW with females being the heterogametic sex (ZW) and males homogametic (ZZ).[8]

Genetic abnormalities such as gynandromorphy also occur from time to time. In addition many butterflies are infected by Wolbachia and infection by the bacteria can lead to the conversion of males into females[9] or the selective killing of males in the egg stage.[10]

Mimicry

Batesian and Mullerian mimicry in butterflies is common. Batesian mimics imitate other species to enjoy the protection of an attribute they do not share, aposematism in this case. The Common Mormon of India has female morphs which imitate the unpalatable red-bodied swallowtails, the Common Rose and the Crimson Rose. Mullerian mimicry occurs when aposematic species evolve to resemble each other, presumably to reduce predator sampling rates, the Heliconius butterflies from the Americas being a good example.

Wing markings called eyespots are present in some species; these may have an automimicry role for some species. In others, the function may be intraspecies communication, such as mate attraction. In several cases, however, the function of butterfly eyespots is not clear, and may be an evolutionary anomaly related to the relative elasticity of the genes that encode the spots.[12][13]

Seasonal polyphenism

Many of the tropical butterflies have distinctive seasonal forms. This phenomenon is termed seasonal polyphenism and the seasonal forms of the butterflies are called the dry-season and wet-season forms. How the season affects the genetic expression of patterns is still a subject of research.[14] Experimental modification by ecdysone hormone treatment has demonstrated that it is possible to control the continuum of expression of variation between the wet and dry-season forms.[15] The dry-season forms are usually more cryptic and it has been suggested that the protection offered may be an adaptation. Some also show greater dark colours in the wet-season form which may have thermoregulatory advantages by increasing ability to absorb solar radiation.[16]

Bicyclus anynana is a species of butterfly that exhibits a clear example of seasonal polyphenism. These butterflies, endemic to Africa, have two distinct phenotypic forms that alternate according to the season. The wet-season forms have large, very apparent ventral eyespots whereas the dry-season forms have very reduced, oftentimes nonexistent, ventral eyespots. Larvae that develop in hot, wet conditions develop into wet-season adults where as those growing in the transition from the wet to the dry season, when the temperature is declining, develop into dry-season adults.[17] This polyphenism has an adaptive role in B. anynana. In the dry-season it is disadvantageous to have conspicuous eyespots because B. anynana blend in with the brown vegetation better without eyespots. By not developing eyespots in the dry-season they can more easily camouflage themselves in the brown brush. This minimizes the risk of visually mediated predation. In the wet-season, these brown butterflies cannot as easily rely on cryptic coloration for protection because the background vegetation is green. Thus, eyespots, which may function to decrease predation, are beneficial for B. anynana to express.[18]

Habits

Butterflies feed primarily on nectar from flowers. Some also derive nourishment from pollen,[19] tree sap, rotting fruit, dung[20], decaying flesh[21], and dissolved minerals in wet sand or dirt. Butterflies are important as pollinators for some species of plants although in general they do not carry as much pollen load as bees. They are however capable of moving pollen over greater distances.[22]

As adults, butterflies consume only liquids and these are sucked by means of their proboscis. They feed on nectar from flowers and also sip water from damp patches. This they do for water, for energy from sugars in nectar and for sodium and other minerals which are vital for their reproduction. Several species of butterflies need more sodium than provided by nectar. They are attracted to sodium in salt and they sometimes land on people, attracted by human sweat. Besides damp patches, some butterflies also visit dung, rotting fruit or carcasses to obtain minerals and nutrients. In many species, this mud-puddling behaviour is restricted to the males, and studies have suggested that the nutrients collected are provided as a nuptial gift along with the spermatophore during mating.[23]

Butterflies sense the air for scents, wind and nectar using their antennae. The antennae come in various shapes and colours. The hesperids have a pointed angle or hook to the antennae, while most other families show knobbed antennae. The antennae are richly covered with sensillae. A butterfly's sense of taste is coordinated by chemoreceptors on the tarsi, which work only on contact, and are used to determine whether an egg-laying insect's offspring will be able to feed on a leaf before eggs are laid on it.[24] Many butterflies use chemical signals, pheromones, and specialized scent scales (androconia) and other structures (coremata or 'Hair pencils' in the Danaidae) are developed in some species.

Vision is well developed in butterflies and most species are sensitive to the ultraviolet spectrum. Many species show sexual dimorphism in the patterns of UV reflective patches.[25] Color vision may be widespread but has been demonstrated in only a few species.[26][27]

Some butterflies have organs of hearing and some species are also known to make stridulatory and clicking sounds.[28]

Many butterflies, such as the Monarch butterfly, are migratory and capable of long distance flights. They migrate during the day and use the sun to orient themselves. They also perceive polarized light and use it for orientation when the sun is hidden.[29]

Many species of butterfly maintain territories and actively chase other species or individuals that may stray into them. Some species will bask or perch on chosen perches. The flight styles of butterflies are often characteristic and some species have courtship flight displays. Basking is an activity which is more common in the cooler hours of the morning. Many species will orient themselves to gather heat from the sun. Some species have evolved dark wingbases to help in gathering more heat and this is especially evident in alpine forms.[30]

Flight

- See also Insect flight

Like many other members of the insect world, the lift generated by butterflies is more than what can be accounted for by steady-state, non-transitory aerodynamics. Studies using Vanessa atalanta in a windtunnel show that they use a wide variety of aerodynamic mechanisms to generate force. These include wake capture, vortices at the wing edge, rotational mechanisms and Weis-Fogh 'clap-and-fling' mechanisms. The butterflies were also able to change from one mode to another rapidly.[31]

Migration

- See also Insect migration

Many butterflies migrate over long distances. Particularly famous migrations are those of the Monarch butterfly from Mexico to northern USA and southern Canada, a distance of about 4000 to 4800 km (2500–3000 miles). Other well known migratory species include the Painted Lady and several of the Danaine butterflies. Spectacular and large scale migrations associated with the Monsoons are seen in peninsular India.[32] Migrations have been studied in more recent times using wing tags and also using stable hydrogen isotopes.[33][34]

Butterflies have been shown to navigate using time compensated sun compasses. They can see polarized light and therefore orient even in cloudy conditions. The polarized light in the region close to the ultraviolet spectrum is suggested to be particularly important.[35]

It is suggested that most migratory butterflies are those that belong to semi-arid areas where breeding seasons are short.[36] The life-histories of their host plants also influence the strategies of the butterflies.[37]

Defense

Butterflies are threatened in their early stages by parasitoids and in all stages by predators, diseases and environmental factors. They protect themselves by a variety of means.

Chemical defenses are widespread and are mostly based on chemicals of plant origin. In many cases the plants themselves evolved these toxic substances as protection against herbivores. Butterflies have evolved mechanisms to sequester these plant toxins and use them instead in their own defense.[38] These defense mechanisms are effective only if they are also well advertised and this has led to the evolution of bright colours in unpalatable butterflies. This signal may be mimicked by other butterflies. These mimetic forms are usually restricted to the females.

Cryptic coloration is found in many butterflies. Some like the oakleaf butterfly are remarkable imitations of leaves.[39] As caterpillars, many defend themselves by freezing and appearing like sticks or branches. Some papilionid caterpillars resemble bird dropping in their early instars. Some caterpillars have hairs and bristly structures that provide protection while others are gregarious and form dense aggregations. Some species also form associations with ants and gain their protection (See Myrmecophile).

Behavioural defenses include perching and wing positions to avoid being conspicuous. Some female Nymphalid butterflies are known to guard their eggs from parasitoid wasps.[40]

Eyespots and tails are found in many lycaenid butterflies and these divert the attention of predators from the more vital head region. An alternative theory is that these cause ambush predators such as spiders to approach from the wrong end and allow for early visual detection.[41]

A butterfly's hind wings are thought to allow the butterfly to take swift, tight turns to evade predators.[42]

Notable species

There are between 15,000 and 20,000 species of butterflies worldwide. Some well-known species from around the world include:

- Swallowtails and Birdwings, Family Papilionidae

- Common Yellow Swallowtail, Papilio machaon

- Spicebush Swallowtail, Papilio troilus

- Lime Butterfly, Papilio demoleus

- Ornithoptera genus (Birdwings; the largest butterflies)

- Whites and Yellows, Family Pieridae

- Small White, Pieris rapae

- Green-veined White, Pieris napi

- Common Jezebel, Delias eucharis

- Blues and Coppers or Gossamer-Winged Butterflies, Family Lycaenidae

- Xerces Blue, Glaucopsyche xerces (extinct)

- Karner Blue, Lycaeides melissa samuelis (endangered)

- Red Pierrot, Talicada nyseus

- Metalmark butterflies, Family Riodinidae

- Duke of Burgundy, Hamearis lucina

- Plum Judy, Abisara echerius

- Brush-footed butterflies, Family Nymphalidae

- Painted Lady, or Cosmopolitan, Vanessa cardui

- Monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus

- Morpho genus

- Speckled Wood, Pararge aegeria

- Skippers, Family Hesperiidae

- Mallow Skipper, Carcharodus alceae

- Zabulon Skipper, Poanes zabulon

In culture

Art

Artistic depictions of butterflies have been used in many cultures including Egyptian hieroglyphs 3500 years ago.[43] Today, butterflies are widely used in various objects of art and jewelry: mounted in frame, embedded in resin, displayed in bottles, laminated in paper, and used in some mixed media artworks and furnishings.[44] Butterflies have also inspired the "butterfly fairy" as an art and fictional character, including in the Barbie Mariposa film.

Symbolism

According to the “Butterflies” chapter in Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, by Lafcadio Hearn, a butterfly is seen as the personification of a person's soul; whether they be living, dying, or already dead. One Japanese superstition says that if a butterfly enters your guestroom and perches behind the bamboo screen, the person whom you most love is coming to see you. However, large numbers of butterflies are viewed as bad omens. When Taira no Masakado was secretly preparing for his famous revolt, there appeared in Kyoto so vast a swarm of butterflies that the people were frightened — thinking the apparition to be a portent of coming evil.[45]

The Russian word for "butterfly", бабочка (bábochka), also means "bow tie". It is a diminutive of "baba" or "babka" (= "woman, grandmother, cake"), whence also "babushka" = "grandmother".

The Ancient Greek word for "butterfly" is ψυχή (psȳchē), which primarily means "soul", "mind".[46]

According to Mircea Eliade's Encyclopedia of Religion, some of the Nagas of Manipur trace their ancestry from a butterfly.[47]

In Chinese culture two butterflies flying together are a symbol of love. Also a famous Chinese folk story called Butterfly Lovers. The Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi once had a dream of being a butterfly flying without care about humanity, however when he woke up and realized it was just a dream, he thought to himself "Was I before a man who dreamt about being a butterfly, or am I now a butterfly who dreams about being a man?"

In some old cultures, butterflies also symbolize rebirth into a new life after being inside a cocoon for a period of time.

Jose Rizal delivered a speech in 1884 in a banquet and mentioned "the Oriental chrysalis ... is about to leave its cocoon" comparing the emergence of a "new Philippines" with that of butterfly metamorphosis.[48] He has also often used the butterfly imagery in his poems and other writings to express the Spanish Colonial Filipinos' longing for liberty.[49] Much later, in a letter to Ferdinand Blumentritt, Rizal compared his life in exile to a weary butterfly with sun-burnt wings.[50]

Some people say that when a butterfly lands on you it means good luck. However, in Devonshire, people would traditionally rush around to kill the first butterfly of the year that they see, or else face a year of bad luck.[51] Also, in the Philippines, a lingering black butterfly or moth in the house is taken to mean that someone in the family has died or will soon die.[52][53]

The idiom "butterflies in the stomach" is used to describe a state of nervousness.

In the NBC television show Kings, butterflies are the national symbol of the fictional nation of Gilboa and a sign of God's favor.

Technological inspiration

Researches on the wing structure of Palawan Birdwing butterflies led to new wide wingspan kite and aircraft designs.[54]

Studies on the reflection and scattering of light by the scales on wings of swallowtail butterflies led to the innovation of more efficient light-emitting diodes.[55]

The structural coloration of butterflies is inspiring nanotechnology research to produce paints that do not use toxic pigments and in the development of new display technologies.

The discoloration and health of butterflies in butterfly farms, is now being studied for use as indicators of air quality in several cities.

See also

- Butterfly Alphabet

- Butterfly zoo

- Differences between butterflies and moths

- Florida Museum of Natural History#McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity

- List of butterflies of Great Britain

- List of butterflies of India

- List of butterflies of Menorca

- List of butterflies of North America

- List of butterflies in Taiwan

- List of butterflies of Tobago

- List of U.S. state butterflies

- List of Australian butterflies

- Moth

Field guides to butterflies

Some field guides to butterfly species include:[56]

- Butterflies of North America, Jim P. Brock and Kenn Kaufman (2003)

- Butterflies through Binoculars: The East, Jeffrey Glassberg (1999)

- Butterflies through Binoculars: The West, Jeffrey Glassberg (2001)

- A Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies, Paul Opler (1994)

- A Field Guide to Western Butterflies, Paul Opler (1999)

- Peterson First Guide to Butterflies and Moths, Paul Opler (1994)

- Las Mariposas de Machu Picchu by Gerardo Lamas (2003)

- The Millennium Atlas of Butterflies in Britain and Ireland by Jim Asher (Editor), et al.

- Pocket Guide to the Butterflies of Great Britain and Ireland by Richard Lewington

- Butterflies of Britain and Europe (Collins Wildlife Trust Guides) by Michael Chinery

- Butterflies of Europe by Tom Tolman and Richard Lewington (2001)

- Butterflies of Europe New Field Guide and Key by Tristan Lafranchis (2004)

- Butterflies of Lebanon by Torben B. Larsen. Beirut. (1974)

- The butterflies of Saudi Arabia and its neighbours. by Torben B. Laren (Stacey intl.) (1984)

- The butterflies of Egypt by Torben B. Larsen (Apollo Books, Denmark). (1990)

- Field Guide to Butterlies of South Africa by Steve Woodhall (2005)

- The butterflies of Kenya and their natural history by Torben B. Larsen (OUP) (1991)

- Butterflies of Sikkim Himalaya and their Natural History by Meena Haribal (1994).

- Butterflies of Peninsular India by Krushnamegh Kunte, Universities Press (2005).

- Butterflies of the Indian Region by Col M. A. Wynter-Blyth, Bombay Natural History Society, Mumbai, India (1957).

- A Guide to Common Butterflies of Singapore by Steven Neo Say Hian (Singapore Science Centre)

- Butterflies of West Malaysia and Singapore by W.A.Fleming. (Longman Malaysia)

- The Butterflies of the Malay Peninsula by A.S. Corbet and H. M. Pendlebury. (The Malayan Nature Society)

- Butterflies of West Africa (two vols.) by Torben B. Larsen. (Apollo Books, Denmark) (2005)

- Oxford Butterflies of India by Thomas Gray, I.D.Kehimkar, J Punetha, Oxford University Press (2008)

Cited references

- ↑ Powell, J. A. 1987. Records of prolonged diapause in Lepidoptera. J. Res. Lepid. 25: 83-109.

- ↑ Devries, P.J. (1988). "The larval ant-organs of Thisbe irenea (Lepidoptera: Riodinidae) and their effects upon attending ants". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 94: 379. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1988.tb01201.x.

- ↑ Devries, Pj (Jun 1990). "Enhancement of Symbioses Between Butterfly Caterpillars and Ants by Vibrational Communication.". Science (New York, N.Y.) 248 (4959): 1104–1106. doi:10.1126/science.248.4959.1104. PMID 17733373.

- ↑ Ehrlich, P. R., and P. H. Raven. 1964. Butterflies and plants: a study in coevolution. Evolution 18:586 – 608

- ↑ Mason, C. W. (1927). The Journal of Physical Chemistry 31: 321. doi:10.1021/j150273a001.

- ↑ Vukusic, P., J. R. Sambles, and H. Ghiradella (2000) Optical Classification of Microstructure in Butterfly Wing-scales. Photonics Science News, 6, 61-66, EX.ac.uk

- ↑ Prum, Ro; Quinn, T; Torres, Rh (Feb 2006). "Anatomically diverse butterfly scales all produce structural colours by coherent scattering." (Free full text). The Journal of experimental biology 209 (Pt 4): 748–65. doi:10.1242/jeb.02051. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 16449568. http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16449568.

- ↑ Traut, W; Marec, F (Aug 1997). "Sex chromosome differentiation in some species of Lepidoptera (Insecta).". Chromosome research : an international journal on the molecular, supramolecular and evolutionary aspects of chromosome biology 5 (5): 283–91. doi:10.1023/B:CHRO.0000038758.08263.c3. ISSN 0967-3849. PMID 9292232.

- ↑ Rousset, F; Bouchon, D; Pintureau, B; Juchault, P; Solignac, M (Nov 1992). "Wolbachia endosymbionts responsible for various alterations of sexuality in arthropods.". Proceedings. Biological sciences / the Royal Society 250 (1328): 91–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.1992.0135. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 1361987.

- ↑ Jiggins, Francis M; Hurst, GD; Schulenburg, JH; Majerus, ME (2001). "Two male-killing Wolbachia strains coexist within a population of the butterfly Acraea encedon". Heredity 86 (Pt 2): 161. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00804.x. PMID 11380661.

- ↑ Meyer, A (Oct 2006). "Repeating patterns of mimicry." (Free full text). PLoS biology 4 (10): e341. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040341. ISSN 1544-9173. PMID 17048984. PMC 1617347. http://biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0040341.

- ↑ Brunetti CR et al. (10 2001). "The generation and diversification of butterfly eyespot color patterns.". J. of Cell Biology 11 (20): 1578–85. PMID 11676917 : 11676917.

- ↑ Brakefield, PM et al. (1996). "Development, plasticity and evolution of butterfly eyespot patterns.". Nature 384 (384): 236–242. doi:10.1038/384236a0. PMID 12809139.

- ↑ Brakefield, Pm; Kesbeke, F; Koch, Pb (Dec 1998). "The regulation of phenotypic plasticity of eyespots in the butterfly Bicyclus anynana.". The American naturalist 152 (6): 853–60. doi:10.1086/286213. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 18811432.

- ↑ Nijhout, Hf (Jan 2003). "Development and evolution of adaptive polyphenisms.". Evolution & development 5 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2003.03003.x. ISSN 1520-541X. PMID 12492404.

- ↑ Brakefield, PAUL M.; Larsen, Torben B. (1984). "The evolutionary significance of dry and wet season forms in some tropical butterflies". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 22: 1. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb00795.x.

- ↑ Lyytinen, A., P. M. Brakefield, L. Lindström, and J. Mappes. 2004. Does predation maintain eyespot plasticity in Bicyclus anynana. The Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 271:279-283.

- ↑ Brakefield, P. M., J. Gates, D. Keys, F. Kesbeke, P. J. Wijngaarden, A. Monteiro, V. French, and S. B. Carroll. 1996. Development, plasticity and evolution of butterfly eyespot patterns. Nature 384:236-242.

- ↑ Gilbert LE (1972). "Pollen feeding and reproductive biology of Heliconius butterflies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 69: 1402–1407. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.6.1403. http://www.pnas.org/content/69/6/1403.abstract.

- ↑ At 7 to 8 pm 27 October 2009 the BBC2 television program Ray Mears's Northern Wilderness showed a butterfly feeding from wolf faeces in the Canadian boreal forest

- ↑ At 7.30 to 8 pm 27 October 2009 the ITV1 television program Grimefighters showed a butterfly feeding from a decaying dead rat in a town in England

- ↑ Herrera, C.M. (1987). "Components of pollinator "quality": comparative analysis of a diverse insect assemblage.". Oikos (Oikos, Vol. 50, No. 1) 50 (1): 79–90. doi:10.2307/3565403. http://ebd06.ebd.csic.es/pdfs/Herrera.1987.Oikos.pdf.

- ↑ Molleman Freerk, Grunsven Roy H. A., Liefting Maartje, Zwaan Bas J., Brakefield Paul M. (2005) Is male puddling behaviour of tropical butterflies targeted at sodium for nuptial gifts or activity? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 86, (3):345-361

- ↑ "Article on San Diego Zoo website". Sandiegozoo.org. http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-butterfly.html. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Obara Y, Hidaki T. (1968). Recognition of the female by the male, on the basis of ultra-violet reflection, in the white cabbage butterfly Pieris rapae crucivora Boisduval. Proc. Japan Acad., 44: 829-832.

- ↑ Tadao Hirota and Yoshiomi Kato 2004 Color discrimination on orientation of female Eurema hecabe (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) Applied Entomology and Zoology Vol. 39:229-233 JST.go.jp

- ↑ Michiyo Kinoshita, Naoko Shimada And Kentaro Arikawa (1999) Color vision of the foraging swallowtail butterfly Papilio xuthus. The Journal of Experimental Biology 202:95 – 102 [1]

- ↑ Swihart, S. L (1967). Hearing in butterflies. J. Insect Physiol 13, 469

- ↑ Reppert, Steven M.; Haisun Zhu; White, Richard H. (2004) Polarized light helps monarch butterflies navigate. Current biology 14(2):155-158

- ↑ Ellers, J. and Carol L. Boggs (2002) The evolution of wing color in Colias butterflies: Heritability, Sex Linkage, and population divergence. Evolution, 56(4):836 – 840 Stanford.edu

- ↑ Srygley, R. B. and A. L. R. Thomas (2002) Aerodynamics of insect flight: flow visualisations with free flying butterflies reveal a variety of unconventional lift-generating mechanisms. Nature 420: 660-664. OX.ac.uk

- ↑ Williams, C. B. 1927 A study of butterfly migration in south India and Ceylon, based largely on records by Messrs. G Evershed, E.E.Green, J.C.F. Fryer and W. Ormiston. Trans. Ent. Soc. London 75:1-33

- ↑ Urquhart, F. A. & N. R. Urquhart. 1977. Overwintering areas and migratory routes of the Monarch butterfly (Danaus p. plexippus, Lepidoptera: Danaidae) in North America, with special reference to the western population. Can. Ent. 109: 1583-1589

- ↑ Wassenaar L.I., Hobson K.A. 1998. Natal origins of migratory monarch butterflies at wintering colonies in Mexico: new isotopic evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 95(26):15436-9. Full text PNAS.org

- ↑ Ivo Sauman, Adriana D. Briscoe, Haisun Zhu, Dingding Shi, Oren Froy, Julia Stalleicken, Quan Yuan, Amy Casselman, and Steven M. Reppert (2005) Connecting the Navigational Clock to Sun Compass Input in Monarch Butterfly Brain. Neuron. 46:457-467 Neuron.org

- ↑ Southwood, T. R. E. 1962. Migration of terrestrial arthropods in relation to habitat. Biol. Rev. 37:171-214

- ↑ Dennis, R L H, Tim G. Shreeve, Henry R. Arnold and David B. Roy (2005) Does diet breadth control herbivorous insect distribution size? Life history and resource outlets for specialist butterflies. Journal of Insect Conservation 9(3):187-200

- ↑ Nishida, Ritsuo (2002). Sequestration of defensive substances from plants by Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47:57–92

- ↑ Robbins, Robert K. (1981) The "False Head" Hypothesis: Predation and Wing Pattern Variation of Lycaenid Butterflies. American Naturalist 118(5):770-775

- ↑ Nafus, D. M. and I. H. Schreiner (1988) Parental care in a tropical nymphalid butterfly Hypolimas anomala. Anim. Behav. 36: 1425- 143

- ↑ William E. Cooper, Jr. (1998) Conditions favoring anticipatory and reactive displays deflecting predatory attack. Behavioral Ecology

- ↑ Hind Wings Help Butterflies Make Swift Turns to Evade Predators Newswise, Retrieved on January 8, 2008.

- ↑ Larsen, Torben (1994) Butterflies of Egypt. Saudi Aramco world. 45(5):24-27 Online

- ↑ "Table complete with real butterflies embedded in resin". Mfjoe.com. http://mfjoe.com/tag/furniture/. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Hearn, Lafcadio (1904). Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Thing. Dover Publications, Inc.. ISBN 0-486-21901-1.

- ↑ Hutchins, M., Arthur V. Evans, Rosser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003) Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Volume 3, Insects, Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, 2003.

- ↑ Rabuzzi, M. 1997. Butterfly etymology. Cultural Entomology November 1997 Fourth issue online

- ↑ "The Best Known Speech of Jose Rizal". Joserizal.info. http://joserizal.info/Writings/Speeches/speeches.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ "The Life and Writings of Dr. Jose Rizal". Joserizal.info. http://joserizal.info/Biography/man_and_martyr/chapter14.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ "193. Rizal, Dapitan, 19 December 1898". Univie.ac.at. http://www.univie.ac.at/Voelkerkunde/apsis/aufi/rizal/rbcor193.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Dorset Chronicle, May 1825, reprinted in: "The First Butterfly", in The Every-day Book and Table Book; or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, Sports, Pastimes, Ceremonies, Manners, Customs, and Events, Each of the Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Days, in Past and Present Times; Forming a Complete History of the Year, Months, and Seasons, and a Perpetual Key to the Almanac, Including Accounts of the Weather, Rules for Health and Conduct, Remarkable and Important Anecdotes, Facts, and Notices, in Chronology, Antiquities, Topography, Biography, Natural History, Art, Science, and General Literature; Derived from the Most Authentic Sources, and Valuable Original Communication, with Poetical Elucidations, for Daily Use and Diversion. Vol III., ed. William Hone, (London: 1838) p 678.

- ↑ "Death practices Philippine style". Sunstar.com.ph. 2005-10-30. http://www.sunstar.com.ph/static/dav/2005/10/30/feat/death.practices.philippine.style.html. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ don.herrington@livinginthephilippines.com. "Superstitions and Beliefs related to Death". Livinginthephilippines.com. http://www.livinginthephilippines.com/philculture/superstitions_and_beliefs.html. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ "An Introduction to The World of Birdwing Butterflies". Nagypal.net. 2000-05-28. http://www.nagypal.net/. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Vukusic, Pete and Ian Hooper. 2005. Directionally Controlled Fluorescence Emission in Butterflies Science. 310(5751):1151 DOI: 10.1126/science.1116612

- ↑ For a more comprehensive list, see the International Field Guides database

Other references

- Boggs, C., Watt, W., Ehrlich, P. 2003. Butterflies: Evolution and Ecology Taking Flight. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

- Darby, Gene, 1958. What Is A Butterfly. Chicago, Benefic Press. pp. 5 – 48.

- Heppner, J. B. 1998. Classification of Lepidoptera. Holarctic Lepidoptera, Suppl. 1.

- Monteiro, A. and N. E. Pierce. 2001. Phylogeny of Bicyclus (Lepidoptera : Nymphalidae) inferred from COI, COII, and EF-1 alpha gene sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 18:264-281.

- Nemos, F. ca. 1895. Europas bekannteste Schmetterlinge. Beschreibung der wichtigsten Arten und Anleitung zur Kenntnis und zum Sammeln der Schmetterlinge und Raupen Oestergaard Verlag, Berlin, (pdf 77MB)

- Peña, C., N. Waklberg, E. Weingartner, U. Kodandaramaiah, S. Nylin, A. V. L. Freitas, and A. V. Z. Brower. 2006. Higher level phylogeny of Satyrinae butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) based on DNA sequence data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40:29-49.

- Pyle, R. M. 1992. Handbook for Butterfly Watchers. Houghton Mifflin. First published, 1984. ISBN 0-395-61629-8

- Stevens, M. 2005. The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews 80:573-588.

External links

General interest

- The Royal Horticultural Society butterfly exhibition

- Papilionoidea on the Tree of Life Web project

- Butterflies on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

Regional lists

- Collodi Butterfly House Tuscany

- Butterflies and Moths of North America

- Butterflies of America

- Butterflies of Canada

- North American Butterfly Association (NABA)

- Butterflies and Moths in the Netherlands

- Butterflies of Spain and Portugal

- Insect and butterfly diversity of Pakistan

- Butterflies of the Philippines

- Butterflies of Southern India

- Butterflies of Sri Lanka

- Butterflies of Singapore

- Israel Insect World

- Singapore Butterfly Checklist

- Butterfly Conservation Society of Taiwan

- Butterflies of Morocco

- Butterflies of Indo-China Chiefly Thailand, Laos and Vietnam.

- Butterflies of Southeastern Sulawesi

- Naturalis Butterflies of Sulawesi (Illustrated pdf)

- Butterflies of Thailand

- Butterflies of Mexico

- Butterflies of Ghana

Literature

- Literaturatenbank Free downloads

Images/Movies

- BugGuide.net Many images of North American butterflies, many licensed via Creative Commons

- Butterfly Pictures and Information

- Butterfly of Brazil

- Reference quality large format photographs, common butterflies of North America

- Gallery of Florida Butterflies and Moths

- Butterfly Picture Gallery

- Photographs of most of the Butterflies in Southern California

- Butterflies of Southern Illinois

- Butterflies of France

- Butterflies of Spain and Portugal

- Butterfly Movies (Tree of Life)

- 1000+ photos of Massachusetts butterflies

- European butterfly pictures - common names and wildlife photography

- Online videos of Skippers of the Northeast-USA