Bunyip

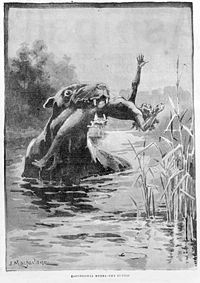

Drawing of a Bunyip in 1890 |

|

| Data | |

|---|---|

| First reported | Early 1800s |

| Country | Australia |

| Region | Throughout Australia |

| Habitat | Water |

The bunyip or kianpraty[1] is a large mythical creature from Aboriginal mythology, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes. The origin of the word bunyip has been traced to the Wemba-Wemba or Wergaia language of Aboriginal people of South-Eastern Australia.[2][3][4] However, the bunyip appears to have formed part of traditional Aboriginal beliefs and stories throughout Australia, although its name varied according to tribal nomenclature.[5] In his 2001 book, writer Robert Holden identified at least nine regional variations for the creature known as the bunyip, across Aboriginal Australia.[4] Various written accounts of bunyips were made by Europeans in the early and mid nineteenth century, as settlement spread across Australia.

Contents |

Meaning

The word bunyip is usually translated by Aboriginal Australians today as "devil" or " evil spirit".[6] However, this translation may not accurately represent the role of the bunyip in Aboriginal mythology or its possible origins before written accounts were made. Some modern sources allude to a linguistic connection between the bunyip and Bunjil, "a mythic 'Great Man' who made the mountains and rivers and man and all the animals."[7] The word bunyip may not have appeared in print in English until the mid 1840s.[8]

By the 1850s, bunyip had also become a "synonym for imposter, pretender, humbug and the like" in the broader Australian community.[2] The term bunyip aristocracy was first coined in 1853 to describe Australians aspiring to be aristocrats. In the early 1990s it was famously used by Prime Minister Paul Keating to describe members of the conservative Liberal Party of Australia opposition.[9]

The word bunyip can be still found in a number of Australian contexts including placenames such as the Bunyip River (which flows into Westernport Bay in southern Victoria) and the town of Bunyip, Victoria.

Characteristics

.jpg)

Descriptions of bunyips vary widely. George French Angus may have collected a description of a bunyip in his account of a "water spirit" from the Moorundi people of the Murray River before 1847, stating it is "much dreaded by them… It inhabits the Murray; but…they have some difficulty describing it. Its most usual form…is said to be that of an enormous starfish"[10] Robert Brough Smyth’s Aborigines of Victoria of 1878 devoted ten pages to the bunyip, but concluded "in truth little is known among the blacks respecting its form, covering or habits; they appear to have been in such dread of it as to have been unable to take note of its characteristics."[11] However, common features in many nineteenth century newspaper accounts include a dog-like face, dark fur, a horse-like tail, flippers, and walrus-like tusks or horns or a duck like bill.[12]

The "Challicum bunyip", an outline image of a bunyip carved by Aborigines into the bank of Fiery Creek, near Ararat, Victoria, was first recorded by The Australasian newspaper in 1851. According to the report, the bunyip had been speared after killing an Aboriginal man. Antiquarian Reynell Johns claimed that until the mid-1850s, Aboriginal people made a "habit of visiting the place annually and retracing the outlines of the figure [of the bunyip] which is about 11 paces long and 4 paces in extreme breadth."[13]

Debate over origins of the bunyip

Non Aboriginal Australians have made various attempts to understand and explain the origins of the bunyip as a physical entity over the past 150 years.

Writing in 1933, Charles Fenner suggested it was likely the "actual origin of the bunyip myth lies in the fact that from time to time seals have made their way up the …Murray and Darling (Rivers)." He provided examples of seals found as far inland as Overland Corner, Loxton and Conargo and reminded readers "the smooth fur, prominent 'apricot' eyes and the bellowing cry are characteristic of the seal."[14]

Another suggestion is that the bunyip may be a cultural memory of extinct Australian marsupials such as the Diprotodon or Palorchestes. This connection was first formally made by Dr. George Bennett of Australian Museum in 1871,[15] but in the early 1990s palaeontologist Pat Vickers-Rich and geologist Neil Archbold also cautiously suggested that Aboriginal legends "perhaps had stemmed from an acquaintance with prehistoric bones or even living prehistoric animals themselves… When confronted with the remains of some of the now extinct Australian marsupials, Aborigines would often identify them as the bunyip."[16]

Another connection to the bunyip is the shy Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus).[17] During the breeding season the male call of this marsh dwelling bird is a "low pitched boom,"[18] hence it is occasionally called the "bunyip bird."[7]

Early accounts collected by Settlers

During the early settlement of Australia by Europeans the notion that the bunyip was an actual unknown animal that awaited discovery became common. Early European settlers, unfamiliar with the sights and sounds of the island continent's peculiar fauna, regarded the bunyip as one more strange Australian animal and sometimes attributed unfamiliar animal calls or cries to it. It has also been suggested that nineteenth century bunyip-lore was reinforced by imported European memories, such as that of the Irish Púca.[7]

A large number of bunyip sightings occurred between 1840s and 1850s, particularly in the southeastern colonies of Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia, as European settlers extended their reach. The following is not an exhaustive list of accounts:

Hume find of 1818

One of the earliest accounts relating to a large unknown freshwater animal was in 1818[19] when Hamilton Hume and James Meehan found some large bones at Lake Bathurst in New South Wales. They did not call the animal a bunyip, but described the remains indicating the creature as very much like a hippopotamus or manatee. The Philosophical Society of Australasia later offered to reimburse Hume for any costs incurred in recovering a specimen of the unknown animal, but for various reasons Hume did not return to the lake.[20]

Wellington Caves fossils 1830

More significant was the discovery of fossilised bones of "some quadruped much larger than the ox or buffalo"[21] in the Wellington Caves in mid 1830 by bushman George Rankin and later, Thomas Mitchell. Sydney's Reverend John Dunmore Lang announced the find as "convincing proof of the deluge."[22] However, it was British anatomist Sir Richard Owen who identified the fossils as the gigantic marsupials Nototherium and Diprotodon. At the same time, some settlers observed "all natives throughout these... districts have a tradition (of) a very large animal having at one time existed in the large creeks and rivers and by many it is said that such animals now exist."[23]

First written use of the word bunyip in 1845

Fossils found near Geelong were revealed by The Geelong Advertiser in July 1845, under the headline Wonderful Discovery of a new Animal. It continued "On the bone being shown to an intelligent black (sic), he at once recognised it as belonging to the bunyip, which he declared he had seen. On being requested to make a drawing of it, he did so without hesitation." The account noted a story of an Aboriginal woman being killed by a bunyip, and the "most direct evidence of all," which was that of a man named Mumbowran, "who showed several deep wounds on his breast made by the claws of the animal." The account provided this description of the creature

| “ | The Bunyip, then, is represented as uniting the characteristics of a bird and of an alligator. It has a head resembling an emu, with a long bill, at the extremity of which is a transverse projection on each side, with serrated edges like the bone of the stingray. Its body and legs partake of the nature of the alligator. The hind legs are remarkably thick and strong, and the fore legs are much longer, but still of great strength. The extremities are furnished with long claws, but the blacks say its usual method of killing its prey is by hugging it to death. When in the water it swims like a frog, and when on shore it walks on its hind legs with its head erect, in which position it measures twelve or thirteen feet in height.[24] | ” |

Shortly after this account appeared, it was repeated in other Australian newspapers. However it appears to be the first use of the word bunyip in a written publication.

The Australian Museum's bunyip of 1847

In January 1846, a peculiar skull was taken from the banks of Murrumbidgee River near Balranald, New South Wales. Initial reports suggested that it was the skull of something unknown to science. The squatter who found it remarked "all the natives to whom it was shown called [it ] a bunyip"[25] By July 1847 several experts had identified the skull as the deformed foetal skull of a foal or calf.[26] At the same time however, the so-called bunyip skull was put on display in the Australian Museum (Sydney) for two days. Visitors flocked to see it and The Sydney Morning Herald said that it prompted many people to speak out about their 'bunyip sightings.'[27]

William Buckley's account of bunyips 1852

Another early written account is attributed to escaped convict William Buckley in his 1852 biography of 30 years living with the Wathaurong people. His 1852 account records "in... Lake Moodewarri [now Lake Modewarre] as well as in most of the others inland...is a...very extraordinary amphibious animal, which the natives call Bunyip." Buckley's account suggests he saw such a creature on several occasions. He adds "I could never see any part, except the back, which appeared to be covered with feathers of a dusky grey colour. It seemed to be about the size of a full grown calf... I could never learn from any of the natives that they had seen either the head or tail."[28] Buckley also claimed the creature was common in the Barwon River and cites an example he heard of an Aboriginal woman being killed by one. He emphasized the Bunyip was believed to have supernatural powers.[29]

In Popular Culture and Fiction

Numerous tales of the bunyip in written literature appeared in the 19th and early 20th century. These included a story in Andrew Lang's The Brown Fairy Book (1904). The Bunyip of Berkeley's Creek[30] is a contemporary Australian children's picture book about a bunyip.

Perhaps the best known bunyip character in Australia is Alexander Bunyip, created by children's author and illustrator Michael Salmon. First appearing in print in The Monster That Ate Canberra[31] in 1972, Alexander Bunyip went on to appear in many other books and even a live-action television series, Alexander Bunyip's Billabong, in which he was portrayed by Mike Meade.[32] A statue of Alexander is planned for the Gungahlin Library.[33]

Another recent depiction of the bunyip appears in the 1989 illustrated children's book A Kangaroo Court.[34]

A bunyip had an important role in the 1930s classic novel Mountain of the Moon (Chander Pahar in Bengali version), written by Bengali author Bibhutibhushan Banerjee.

The word bunyip has been used in other Australian contexts including The Bunyip newspaper as the banner of a local weekly newspaper published in the town of Gawler, South Australia. First published as a pamphlet by the Gawler Humbug Society in 1863, the name was chosen because, "the Bunyip is the true type of Australian Humbug!"[35] The word is also used in numerous other Australian contexts, including the House of the Gentle Bunyip, in Clifton Hill, Victoria.[36] There is also a coin operated Bunyip at Murray Bridge, South Australia at Sturt Reserve on the town's river front.[37]

Since World War II the bunyip has undergone some cultural crossover from Australia to the United States and beyond; as it now appears as a character in several role-playing and computer games such as; Garou Tribes (Werewolf: The Apocalypse) and as the name of a summoned creature in the popular MMORPG game, RuneScape. The bunyip is also a monster in AdventureQuest. This version is a magical, heavily built creature of the night that is part jackrabbit, part wolf, and part giant.

The cultural cross over from Australia to the USA may have some connection to the use of a bunyip (bunyap) as the symbol of the U.S. Air Force's 7th Fighter Squadron,[38] which was based in Australia in 1942, shortly after its formation. In addition, during the 1950s and 1960s, "Bertie the Bunyip" was a children's show in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, created by Lee Dexter, an Australian.[39]

Bunyips were featured on The Secret Saturdays in the episode "Into the Mouth of Darkness" with their vocal effects provided by Dee Bradley Baker. Here, the bunyips were depicted as small, furry, mischievous cryptids that resemble the Tasmanian Devil of Looney Tunes with small antlers.

The bunyip was also featured repeatedly on the US WB Soap "Charmed", most notably the episode "Nymphs Just Wanna Have Fun", where they're described as neither good nor evil [40].

Naomi Novik includes bunyips as a dangerous adversary in the Australian outback in Tongues of Serpents, the sixth installment of her novels of alternate Napoleonic-history era with dragons.

See also

- Yara-ma-yha-who, a creature from Australian Aboriginal mythology

- Min Min light, an unexplained phenomenon that may have its origins in Australian Aboriginal mythology

- Yowie or Wowee, a creature that has its origins in Australian Aboriginal mythology

- Australian Aboriginal mythology#Rainbow Serpent

- P. A. Yeomans, inventor of the Bunyip Slipper Imp, a plough for developing watersheds

- Marsupial Lion, possible explanation.

External links

- Bunyips ... enter the lair of the bunyip if you dare - interactive for kids / National Library of Australia

References

- ↑ E.E.Morris(1898) Austral English; A Dictionary of Australasian words, Phrases and Usages. p.65-66. McMillan and Co, New York. Reprinted Gale Research Company, Book Tower, Detroit, USA, 1968. [1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Joan Hughes (ed.)(1989) Australian Words and Their Origins. p.90. Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 019553087X

- ↑ Susan Butler (2009) The Dinkum Dictionary; The origin of Australian Words p.53. Text Publishing, Melbourne. ISBN 9781921351983

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Robert Holden (2001) Bunyips: Australia's folklore of fear. pps.15 National Library of Australia. ISBN 0642197327

- ↑ Bill Wannan(1970) Australian Folklore, p.101. Reprinted 1976. Lansdowne Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0 7018 0088 7

- ↑ See for example, Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker)'s story in Stradbroke Dreamtime. [2]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Gwenda Davey and Graham Seal(eds)(1993) The Oxford Companion to Australian Folklore, p.55-5. Oxford University Press, Melbourne ISBN 0195530578

- ↑ See Geelong Advocate July 2, 1845 at Peter Ravenscroft’s Bunyip and Inland Seal Archive[3]

- ↑ "Parliamentary decorum". http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=1732.

- ↑ George French Angus(1847) Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand. Vol 1, p.99. London. Reprinted 1969 Libraries Board of South Australia.

- ↑ Smyth cited in Robert Holden (2001) p.175

- ↑ For numerous examples see Peter Ravenscroft’s survey of nineteenth century newspaper accounts of the bunyip at The Bunyip and Inland Seal Archive [4]

- ↑ Johns cited in Robert Holden(2001) p.176. The page also reprints a drawing of the outline, which no longer exists.

- ↑ Charles Fenner (1933) Bunyips and Billabongs. pps.2-6. Angus and Robertson, Sydney

- ↑ Robert Holden(2001) p.90

- ↑ P.Vikers-Rich, J.M.Monaghan,R.F.Baird and T.H.Rich (eds) (1991)Vertebrate Palaeontology of Australasia. p.2. Pioneer Design Studio and Monash University. ISBN 0909674361. They also note that "legends about the mihirung paringmal of western Victorian Aborigines …may allude to the …extinct giant birds the Dromornithidae."

- ↑ Charles Fenner(1933) p.6

- ↑ Ken Simpson, Nicolas Day and Peter Trusler(1999) Field Guide to the Birds of Australia p.72 Viking Books, Australia. ISBN 0670 879185

- ↑ Robert Holden(2001) p.86

- ↑ See minutes cited (19 December 1821) in Peter Ravenscroft's The Bunyip and Inland Seal Archive[5]

- ↑ George Rankin cited in Robert Holden(2001) p.86

- ↑ J.D.Lang cited in Robert Holden(2001) p.86

- ↑ cited in Robert Holden(2001) p.88

- ↑ The Geelong Advertiser 2 July 1845 in Peter Ravenscroft's The Bunyip and Inland Seal Archive[6]

- ↑ Cited in Robert Holden(2001) p. 91

- ↑ W.S.Macleay and later, Professor Owen cited in Robert Holden(2001) pps.92-3

- ↑ Bunyips - Evidence

- ↑ Tim Flannery(Ed.)(2002): The Life and Adventures of William Buckley; 32 Years a wanderer amongst the Aborigines of the then unexplored country around Port Phillip, now the Province of Victoria by John Morgan. First published 1852. This edition, Text Publishing, Melbourne Australia. p.66. ISBN 1877008206

- ↑ Tim Flannery(Ed.)(2002) The Life and Adventures of William Buckley. p.138-9

- ↑ The Bunyip of Berkeley's Creek, Jenny Wagner ISBN 0-14-050126-6

- ↑ The Monster That Ate Canberra ISBN 0-957-95504-9, Michael Salmon

- ↑ Bunyip at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ (in English) Bunyip coming to Gungahlin. Australia: WIN News. 2009-09-04. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iphfduKumo0. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ A Kangaroo Court ISBN 0-333-45032-9, Mary O'Toole, illustrated by Keith McEwan

- ↑ "The Bunyip". Home Page. The Bunyip, (Gawler's Weekly Newspaper). 2000-06-07-06-07. http://www.bunyippress.com.au/fixed/history.html. Retrieved 2007-05-26. "Beneath the nineteenth-century dignity of colonial Gawler ran an undercurrent of excitement. Somewhere in the mildness of the spring afternoon an antiquated press clacked out a monotonous rhythm with a purpose never before known in the town. Then the undercurrent burst in a wave of jubilation - Gawler's first newspaper, "The Bunyip", was on the streets."

- ↑ The 1860s house was saved from demolition by community action and redeveloped as a home for low income people.

- ↑ "What to See & Do in Murray Bridge". Murray Bridge Tourism Information. Adelaide Hills On-Line. http://www.adhills.com.au/tourism/towns/murraybridge/attractions.html. Retrieved 2007-05-26. "When a coin is inserted in the machine the Bunyip raises from the depths of its cave, booming forth its loud ferocious roar."

- ↑ currently based at Holloman AFB, New Mexico

- ↑ Bertie The Bunyip

- ↑ http://charmed.wikia.com/wiki/Bunyip

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||