Brisbane

| Brisbane Queensland |

|||||||

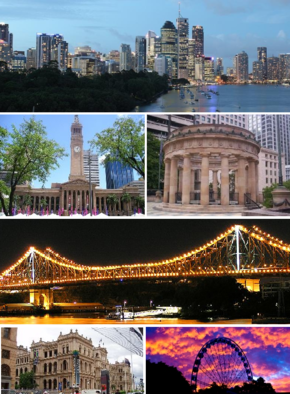

Top: Brisbane CBD, centre left: Brisbane City Hall, centre right: Shrine of Remembrance, centre: Story Bridge, bottom left: Conrad Treasury Casino, bottom right: Wheel of Brisbane. |

|||||||

Brisbane

|

|||||||

| Population: | 2,004,262 (2009)[1][2][3] (3rd) | ||||||

| • Density: | 918/km² (2,377.6/sq mi) (2006)[4] | ||||||

| Established: | 1824 | ||||||

| Area: | 5904.8 km² (2,279.9 sq mi) [5] | ||||||

| Time zone: | AEST (UTC+10) | ||||||

| Location: | |||||||

| LGA: | Brisbane, Ipswich, Logan, Moreton Bay, Redland, Scenic Rim | ||||||

| Region: | South East Queensland | ||||||

| County: | Stanley | ||||||

| State District: | various (38) | ||||||

| Federal Division: |

|

||||||

|

|||||||

Brisbane (pronounced /ˈbrɪzbən/[6]) is the capital and most populous city in the Australian state of Queensland and the third most populous city in Australia.[7] Brisbane's metropolitan area has an approximate population of 2 million[7]. A resident of Brisbane is commonly known as a "Brisbanite"[8].

The Brisbane central business district stands on the original settlement and is situated a bend of the Brisbane River approximately 23 kilometres from its mouth at Moreton Bay. The metropolitan area extends in all directions along the floodplain of the Brisbane River valley between the bay and the Great Dividing Range. While the city is governed by several municipalities, they are centred around the Brisbane City Council which has jurisdiction over the largest area and population in metropolitan Brisbane and is also Australia's largest Local Government Area by population.

Brisbane is named after the river on which it sits which, in turn, was named after Sir Thomas Brisbane, the Governor of New South Wales from 1821 to 1825. The first European settlement in Queensland was a penal colony at Redcliffe, 28 kilometres (17 mi) north of the Brisbane central business district, in 1824. That settlement was soon abandoned and moved to North Quay in 1825. Free settlers were permitted from 1842. Brisbane was chosen as the capital when Queensland was proclaimed a separate colony from New South Wales in 1859.

The city played a central role in the Allied campaign during World War II as the South West Pacific headquarters for General Douglas MacArthur. Brisbane has hosted many large cultural and sporting events including the 1982 Commonwealth Games, World Expo '88 and the final Goodwill Games in 2001. In 2008, Brisbane was classified as a gamma world city+ in the World Cities Study Group’s inventory by Loughborough University.[9] It was also rated the 16th most liveable city in the world in 2009 by The Economist.

Contents |

History

Prior to European settlement, the Brisbane area was inhabited by the Turrbal and Jagera people,[10] whose ancestors migrated to the region from across the Torres Strait. They knew the area as Mian-jin, meaning "place shaped as a spike".

The Moreton Bay area was initially explored by Matthew Flinders. On 17 July 1799, Flinders landed at what is now known as Woody Point, which he named "Red Cliff Point", after the red-coloured cliffs visible from the bay.[11] In 1823, Governor of New South Wales, Thomas Brisbane, instructed that a new northern penal settlement be developed, and an exploration party led by John Oxley further explored Moreton Bay. Oxley discovered, named and explored the Brisbane River as far as Goodna, 20 kilometres (12 mi) upstream from the Brisbane central business district.[12] Oxley recommended Red Cliff Point for the new colony, reporting that ships could land at any tide and easily get close to the shore.[13]

The party settled in Redcliffe on 13 September 1824, under the command of Lieutenant Henry Miller with 14 soldiers—some with wives and children—and 29 convicts. However, this settlement was abandoned after a year, and the colony was moved to a site on the Brisbane River now known as North Quay, 28 kilometres (17 mi) south, that offered a more reliable water supply. Chief Justice Forbes gave the new settlement the name of Edenglassie before it was named Brisbane.[14]

Non-convict European settlement of the Brisbane region commenced in 1838.[15] German missionaries settled at Zions Hill, Nundah, as early as 1837, five years before Brisbane was officially declared a free settlement. The band consisted of two ministers, Christopher Eipper (1813–1894) and Carl Wilhelm Schmidt, and lay missionaries Haussmann, Johann Gottried Wagner, Niquet, Hartenstein, Zillman, Franz, Rode, Doege and Schneider.[16] They were allocated 260 hectares and set about establishing the mission, which became known as German Station.[17]

Free settlers entered the area over the following five years and by the end of 1840 Robert Dixon began work on the first plan of Brisbane Town in anticipation of future development.[18] Queensland was proclaimed a separate colony on 6 June 1859,[19] with Brisbane chosen as its capital, although it was not incorporated as a city until 1902. Over twenty small municipalities and shires were amalgamated in 1925, to form the City of Brisbane which is governed by the Brisbane City Council.[20][21]

1930 was a significant year for Brisbane, with the construction of landmarks that helped define the character of the city. The Story Bridge and Brisbane City Hall, then the city's tallest buildings, were both completed. Additionally, the Shrine of Remembrance, in ANZAC Square, became Brisbane's main war memorial.[22]

During World War II, Brisbane became central to the Allied campaign when the AMP Building (now called MacArthur Central) was used as the South West Pacific headquarters for General Douglas MacArthur, chief of the Allied Pacific forces. MacArthur had previously rejected use of the University of Queensland complex as his headquarters, as the distinctive bends in the river at St Lucia could have aided enemy bombers. Also used as a headquarters by the American troops during World War II was the T & G Building.[23] Approximately 1,000,000 US troops passed through Australia during the war, as the primary coordination point for the South West Pacific.[24] In 1942 Brisbane was the site of a violent clash between visiting US military personnel and Australian servicemen and civilians which resulted in one death and several injuries. This incident became known colloquially as the Battle of Brisbane.[25]

Postwar Brisbane had developed a "big country town" stigma, an image the city's politicians and marketers were very keen to remove.[26][27] Despite steady growth, Brisbane's development was punctuated by infrastructure problems. The State government under Joh Bjelke-Petersen began a major program of change and urban renewal, beginning with the Central Business District (CBD) and inner suburbs. Trams in Brisbane were a popular mode of public transport, and the city became the last Australian city to completely close its tram network in 1969. The 1974 Brisbane flood was a major disaster which temporarily crippled the city. During this era, Brisbane grew and modernised rapidly becoming a destination of interstate migration. Some of Brisbane's popular landmarks were lost, including the Bellevue Hotel in 1977 and Cloudland in 1982, demolished in controversial circumstances by the Deen Brothers demolition crew. Major public works included the Riverside Expressway, the Gateway Bridge, and later, the redevelopment of South Bank, starting with the Queensland Art Gallery.

Brisbane hosted the 1982 Commonwealth Games and the 1988 World Exposition (known locally as World Expo 88). These events were accompanied by a scale of public expenditure, construction and development not previously seen in the state of Queensland.[28][29]

Brisbane's population growth has exceeded the national average every year since 1990 at an average rate of around 2.2% per year.

Geography

Brisbane is in the southeast corner of Queensland, Australia. The city is centred along the Brisbane River, and its eastern suburbs line the shores of Moreton Bay. The greater Brisbane region is on the coastal plain east of the Great Dividing Range. Brisbane's metropolitan area sprawls along the Moreton Bay floodplain from Caboolture in the north to Beenleigh in the south, and across to Ipswich in the south west.

The city of Brisbane is hilly.[30] The urban area, including the central business district, are partially elevated by spurs of the Herbert Taylor Range, such as the summit of Mount Coot-tha, reaching up to 300 metres (980 ft) and the smaller Enoggera Hill. Other prominent rises in Brisbane are Mount Gravatt and nearby Toohey Mountain. Mount Petrie at 170 metres (560 ft) and the lower rises of Highgate Hill, Mount Ommaney, Stephens Mountain and Whites Hill are dotted across the city.

The city is on a low-lying floodplain. Many suburban creeks criss-cross the city, increasing the risk of flooding. The city has suffered two major floods since colonisation, in 1893 and 1974. The 1974 Brisbane flood occurred partly as a result of "Cyclone Wanda". Heavy rain had fallen continuously for three weeks before the Australia Day weekend flood (26 – 27 January 1974).[31] The flood damaged many parts of the city, especially the suburbs of Oxley, Bulimba, Rocklea, Coorparoo, Toowong and New Farm. The City Botanic gardens were inundated, leading to a new colony of mangroves forming in the City Reach of the Brisbane River.[32]

Urban Structure

The Brisbane central business district (CBD) lies in a curve of the Brisbane river. The CBD covers only 2.2 km2 (0.8 sq mi) and is walkable.

Central streets are named after members of the royal family. Queen Street is Brisbane's traditional main street. Streets named after female members (Adelaide, Alice, Ann, Charlotte, Elizabeth, Margaret, Mary) run parallel to Queen Street and Queen Street Mall (named in honour of Queen Victoria) and perpendicular to streets named after male members (Albert, Edward, George, William).

The city has retained some heritage buildings dating back to 1820s. The Old Windmill, in Wickham Park, built by convict labour in 1824,[33][34] is the oldest surviving building in Brisbane. The Old Windmill was originally used for the grinding of grain and a punishment for the convicts who manually operated the grinding mill. The Old Windmill tower’s other significant claim to fame, largely ignored, is that the first television signals in the southern hemisphere were transmitted from it by experimenters in April 1934 — long before TV commenced in most places. These experimental TV broadcasts continued until World War II.[33]

The Old Commissariat Store, on William Street, built by convict labour in 1828, was originally used partly as a grainhouse, has also been a hostel for immigrants and used for the storage of records. Built with Brisbane tuff from the nearby Kangaroo Point Cliffs and sandstone from a quarry near today's Albion Park Racecourse, it is now the home of the Royal Historical Society of Brisbane. It contains a museum and can also be hired for small functions.[35][36][37]

The city has a density of 379.4 people per square kilometre, which is high for an Australian city and comparable to that of Sydney. However like many western cities, Brisbane sprawls into the greater metropolitan area. The lower population density reflects the fact that most of Brisbane's housing stock consists of detached houses.

Early legislation decreed a minimum size for residential blocks resulting in few terrace houses being constructed in Brisbane. Recently the density of the city and inner city neighbourhoods has increased with the construction of apartments, with the result that the population of the central business district has doubled over the last 5 years[38] and closing the gap on Sydney and Melbourne.[39]

The high density housing that existed came in the form of miniature Queenslander-style houses which resemble the much larger traditional styles but are sometimes only one quarter the size. These miniature Queenslanders are becoming scarce but can still be seen in the inner city suburbs.

Multi residence accommodations (such as apartment blocks) are relatively new to Brisbane, with few such blocks built before 1970, other than in inner suburbs such as New Farm. Pre-1950 housing was often built in a distinctive architectural style known as a Queenslander, featuring timber construction with large verandahs and high ceilings. The relatively low cost of timber in South-East Queensland meant that until recently most residences were constructed of timber, rather than brick or stone. Many of these houses are elevated on stumps (also called "stilts"), that were originally timber, but are now frequently replaced by steel or concrete.

Currently, Brisbane has two buildings greater than 200 metres in height. The tallest is Riparian Plaza, which measures 250 metres. Aurora Tower is the tallest building to roof height, at 207 metres, although it will be overtaken by the currently under construction Soleil and Infinity.

|

|

|

|

Climate

Brisbane has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) with hot, humid summers and dry, mild winters.[40] From November through March, thunderstorms are common over Brisbane, with the more severe events accompanied by large damaging hail stones, torrential rain and destructive winds.

The city's highest recorded temperature was 43.2 °C (110 °F) on 26 January 1940. On 19 July 2007, Brisbane's temperature fell below the freezing point for the first time since records began, registering −0.1 °C (31.8 °F) at the airport.[41]

Brisbane's wettest day was 21 January 1887, when 465 millimetres (18.3 in) of rain fell on the city, the highest maximum daily rainfall of Australia's capital cities.

From 2006 until 2010, Brisbane and surrounding temperate areas had been experiencing the most severe drought in over a century, with dam levels dropping below one quarter of their capacity. Residents were mandated by local laws to observe level 6 water restrictions on gardening and other outdoor water usage. Per capita water usage is below 140 litres per day, giving Brisbane one of the lowest per capita usages of water of any Western city in the world.[42] A reversal of fortune in early 2010 has seen Brisbane's water storage climb to over 98% of maximum capacity.

Dust storms in Brisbane are extremely rare; on 23 September 2009, however, a severe dust storm blanketed Brisbane, as well as other parts of eastern Australia.[43][44]

| Climate data for Brisbane | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 43.2 (109.8) |

41.7 (107.1) |

37.9 (100.2) |

33.7 (92.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

35.4 (95.7) |

35.1 (95.2) |

38.7 (101.7) |

34.0 (93.2) |

40.0 (104) |

43.2 (109.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

30.0 (86) |

28.9 (84) |

27.2 (81) |

24.5 (76.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.2 (81) |

27.8 (82) |

29.4 (84.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.8 (67.6) |

17.3 (63.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.8 (49.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.2 (54) |

10.0 (50) |

5.0 (41) |

5.0 (41) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 95.9 (3.776) |

127.7 (5.028) |

89.3 (3.516) |

56.3 (2.217) |

63.6 (2.504) |

59.6 (2.346) |

23.0 (0.906) |

35.6 (1.402) |

26.3 (1.035) |

61.3 (2.413) |

116.2 (4.575) |

128.4 (5.055) |

883.3 (34.776) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 11.7 | 11.8 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 119.9 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[45] | |||||||||||||

Governance

Unlike other Australian capital cities, a large portion of the greater metropolitan area of Brisbane is controlled by a single local government entity, the Brisbane City Council, inside the City of Brisbane LGA. Since the creation of the Brisbane City Council in 1925 the urban areas of Brisbane have expanded considerably past the City Council boundaries[46]. Prior to that, a far smaller area (comprising the inner suburbs of Brisbane today) was controlled by the Brisbane Municipal Council.

Brisbane City Council is the largest local government body (in terms of population and budget) in Australia. The Council, formed by the merger of twenty smaller councils in 1925, has jurisdiction over an area of 1,367 km2 (528 sq mi). The Council's annual budget is approximately $1.6 billion, and it has an asset base of $13 billion.[47]

The remainder of the metropolitan area falls into the LGAs of Logan City to the south, Moreton Bay Region in the northern suburbs, the City of Ipswich to the south west, Redland City to the south east on the bayside, with a small strip in on the far east of the Scenic Rim Region.

Economy

Brisbane has the largest economy of any city between Sydney and Singapore, and has seen consistent economic growth in recent years as a result of the resources boom. White-collar industries include information technology, financial services, higher education and public sector administration generally concentrated in and around the central business district and recently established office areas in the inner suburbs.

Blue-collar industries, including petroleum refining, stevedoring, paper milling, metalworking and QR railway workshops, tend to be located on the lower reaches of the Brisbane River and in new industrial zones on the urban fringe. Tourism is an important part of the Brisbane economy, both in its own right and as a gateway to other areas of Queensland.[48]

Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Queensland State Government has been developing technology and science industries in Queensland as a whole, and Brisbane in particular, as part of its "Smart State" initiative.[49] The government has invested in several biotechnology and research facilities at several universities in Brisbane. The Institute for Molecular Bioscience at the University of Queensland (UQ) Saint Lucia Campus is a large CSIRO and Queensland state government initiative for research and innovation that is currently being emulated at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Campus at Kelvin Grove with the establishment of the Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation (IHBI).[50]

Brisbane is one of the major business hubs in Australia.[51] Most major Australian companies, as well as numerous international companies, have contact offices in Brisbane, while numerous electronics businesses have distribution hubs in and around the city. DHL Global's Oceanic distribution warehouse is located in Brisbane, as is Asia Pacific Aerospace's headquarters. Home grown major companies include Suncorp-Metway Limited, Flight Centre, Sunsuper, Orrcon, Credit Union Australia, Boeing Australia, Donut King, Wotif.com, WebCentral, PIPE Networks, Krome Studios, NetBox Blue, Mincom Limited, TechnologyOne and Virgin Blue.

Brisbane has the fourth highest median household income of the Australian capital cities at $40,973.[52]

Port of Brisbane

The Port of Brisbane is on the lower reaches of the Brisbane River and on Fisherman's Island at the rivers mouth, and is the 3rd most important port in Australia for value of goods.[53] Container freight, sugar, grain, coal and bulk liquids are the major exports. Most of the port facilities are less than three decades old and some are built on reclaimed mangroves and wetlands.

The Port is a part of the Australia TradeCoast, the country's fastest-growing economic development area.[54] Geographically, Australia TradeCoast occupies a large swathe of land around the airport and port. Commercially, the area has attracted a mix of companies from throughout the Asia Pacific region.[54]

Retail

Brisbane has a range of retail precincts, both in the Central Business District and in surrounding suburbs. The Queen Street Mall has a vast array of cafes, restaurants, cinemas, gift shops and shopping centres including: Wintergarden, Broadway on the Mall, QueensPlaza, Brisbane Arcade, Queen Adelaide Building, Tattersalls Arcade and The Myer Centre.

The majority of retail business is done within the suburbs of Brisbane in shopping centres which include major department store chains. There are 3 major Westfield shopping centres in Brisbane located in the suburbs of Chermside (Westfield Chermside), Mount Gravatt (Westfield Garden City) and Carindale (Westfield Carindale).[55]

Other large shopping centres exist at Indooroopilly (Indooroopilly Shopping Centre), Toombul (Centro Toombul) and Mitchelton (Brookside Shopping Centre). Other major shopping centres through-out the metropolitan area include North Lakes (Westfield North Lakes), Strathpine (Westfield Strathpine) and Loganholme (Logan Hyperdome).

Demographics

| Significant overseas born populations[56] | |

| Country of birth | Population (2006) |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 95,315 |

| New Zealand | 73,128 |

| South Africa | 12,824 |

| Vietnam | 11,857 |

| People's Republic of China | 11,418 |

| Philippines | 9,871 |

| Germany | 8,645 |

| India | 7,544 |

| Netherlands | 7,014 |

| Fiji | 6,791 |

| Papua New Guinea | 6,706 |

| Italy | 6,704 |

| Malaysia | 6,686 |

| United States | 6,057 |

| Hong Kong | 6,036 |

| South Korea | 4,841 |

| Brisbane population by year |

||

|---|---|---|

| 1859 | 6,000 | |

| 1942 | 750,000 | |

| 2010 | 2,000,000[57] | |

| 2026 | 2,908,000[57] | Projected |

| 2056 | 4,955,100[57] | Projected |

The statistical division of Brisbane includes much of Brisbane's Local Government Area as well as the cities of Ipswich, Moreton Bay, Logan City and Redland City which demographically are part of a single conurbation. The 2006 census reported 1,763,131 residents within the Brisbane Statistical Division, making it the third largest city in Australia.[58] Brisbane recorded the largest growth rate of all capital cities in the last Census, with an annual growth rate of 2.2%.[59] The median age across the city was 35 years.[5]

The 2006 census showed that 1.7% of Brisbane's population were of indigenous origin and 21.7% were born overseas. Of those born outside of Australia, the three main countries of birth were New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom.

Approximately 16.1% of households spoke a language other than English, with the most common languages being Mandarin 1.1%, Vietnamese 0.9%, Cantonese 0.9%, Italian 0.6% and Samoan 0.5%. Areas of significant overseas populations were in the southern region of Moorooka where those of African descent reside. Most of the Vietnamese population reside in the suburbs of Darra and Inala while those from Mainland China are often found not in one particular area but all around Brisbane. Sunnybank is where most of the majority of the Chinese population reside, consisting mainly of people from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Brisbane has the highest population of Republic of China (Taiwanese) citizens in Australia. It has been estimated that the population has grown to an estimated 35 000+, making them the highest Asian population in Brisbane. Consequently, Sunnybank and its surrounding suburbs have often been dubbed as the "Real Chinatown" and "Taiwan Town".

The inner southern suburbs were considered the most densely populated areas of Southern European descent, primarily Greek and Italian. There are also a major number of Bosnians, Croatians, Indians, Pakistanis, South Africans and Fijians in the city.

Education

Brisbane has multi-campus universities and colleges including the University of Queensland, Queensland University of Technology and Griffith University. Other universities which have campuses in Brisbane include the Australian Catholic University, Central Queensland University, James Cook University, University of Southern Queensland and the University of the Sunshine Coast.

There are three major TAFE colleges in Brisbane; the Brisbane North Institute of TAFE, the Metropolitan South Institute of TAFE, and the Southbank Institute of TAFE.[60] Brisbane is also home to numerous other independent tertiary education providers, including the Australian College of Natural Medicine, the Brisbane College of Theology, QANTM, as well as Jschool: Journalism Education & Training.

The majority of Brisbane's preschool, primary, and secondary schools are run under the jurisdiction of Education Queensland, a branch of the Queensland Government.[61] There are also a large number of independent and Roman Catholic run schools.

Culture

Arts and entertainment

Brisbane has a growing live music scene, both popular and classical. The Queensland Performing Arts Centre (QPAC), which is located at South Bank, consists of the Lyric Theatre, a Concert Hall, Cremorne Theatre and the Playhouse Theatre. The Queensland Ballet, Opera Queensland, Queensland Theatre Company and other performance art groups stage performances in the different venues. It is also the major performing venue for The Queensland Orchestra, Brisbane's only professional symphony orchestra and Queensland's largest performing arts company. The Queensland Conservatorium, in which professional companies and Conservatorium students also stage performances, is located within the South Bank Parklands.

Brisbane is home to arguably the largest community choral scene in Australia. Numerous choirs present countless performances across the city annually. These choirs include the Brisbane Chorale, Queensland Choir, Brisbane Chamber Choir, Canticum Chamber Choir, Brisbane Concert Choir, Imogen Children's Chorale and Brisbane Birralee Voices. Due to the lack of a suitable purpose built performance venue for choral music, these choirs typically perform in the city's many churches with The Cathedral of St Stephen and St John's Cathedral perhaps presenting more choral music performances than any other venue in the city.

The Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), opened in December 2006, is one of the latest additions to the South Bank precinct and houses some of the most well-known pieces of modern art from within and outside Australia. GOMA is the largest modern art gallery in Australia. GOMA holds the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) which focuses on contemporary art from the Asia and Pacific in a variety of media from painting to video work. In Addition, its size enables the gallery to exhibit particularly large shows — the Andy Warhol exhibition being the largest survey of his work in Australia. GOMA also boasts Australia's largest purpose-built Cinémathèque. The Gallery of Modern Art is located next to the State Library of Queensland and the Queensland Art Gallery.

Along with Beijing, Berlin, Birmingham and Marseille, Brisbane was nominated as one of the Top 5 International Music Hotspots by Billboard in 2007. There are also popular entertainment pubs and clubs within both the City and Fortitude Valley.[62][63]

The Brisbane Powerhouse in New Farm and the Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts on Brunswick Street in Fortitude Valley also feature diverse programs featuring exhibitions and festivals of visual art, music and dance.

The La Boite Theatre Company performs at the Roundhouse Theatre at Kelvin Grove. Twelfth Night Theatre at Bowen Hills is also a professional theatre. The Powerhouse complex stages a range of productions.

There are numerous amateur theatre groups in Brisbane. The oldest is the Brisbane Arts Theatre which was founded in 1936. It has a regular adult and children's theatre and is located in Petrie Terrace.

Annual events

Major cultural events in Brisbane include the Ekka (the Royal Queensland Show), held each August, and the Riverfestival, held each September at South Bank Parklands and surrounding areas. Warana, (meaning Blue Skies), was a former spring festival which began in 1961 and was held in September each year. Run as a celebration of Brisbane, Warana was similar to Melbourne's Moomba festival. In 1996 the annual festival was changed to a biennial Brisbane Festival.[64]

The Brisbane International Film Festival (BIFF) is held in July/August in a variety of venues around Brisbane including the Regent Cinema in Queen Street Mall. BIFF features new films and retrospectives by domestic and international filmmakers along with seminars and awards.

The Paniyiri festival at Musgrave Park (corner of Russell and Edmondstone Streets, South Brisbane) is an annual Greek cultural festival held on the first weekend in May. The Brisbane Medieval Fayre and Tournament is held each June in Musgrave Park.

The Valley Fiesta is an annual three-day event organised by the Valley Chamber of Commerce. It was launched by Brisbane Marketing in 2002 to promote Fortitude Valley as a hub for arts and youth culture. It features free live music, market stalls, food and drink from many local restaurants and cafés, and other entertainment.

The Bridge to Brisbane fun run has become a major annual charity event for Brisbane.

Tourism and recreation

Mount Coot-tha

Tourism plays a major role in Brisbane's economy, being the third-most popular destination for international tourist after Sydney and Melbourne.[65] Popular tourist and recreation areas in Brisbane include the South Bank Parklands, Roma Street Parkland, the City Botanic Gardens, Brisbane Forest Park and Portside Wharf. The Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary opened in 1927 and was the world's first koala sanctuary.[66]

The suburb of Mount Coot-tha is home to a popular state forest, and the Brisbane Botanic Gardens which houses the Sir Thomas Brisbane Planetarium and the "Tsuki-yama-chisen" Japanese Garden (formerly of the Japanese Government Pavilion of Brisbane's World Expo '88).

Brisbane has over 27 km (16.8 mi) of bicycle pathways, mostly surrounding the Brisbane river and city centre, extending to the west of the city.[67] The river itself was popular with bathers, and it permitted boating excursions to Moreton Bay when the main port was in the city reaches.[66] Today fishing and boating are more common. Other popular recreation activities include the Story Bridge adventure climb and rock climbing at the Kangaroo Point cliffs.

Sport

Brisbane has hosted several major sporting events including the 1982 Commonwealth Games and the 2001 Goodwill Games. The city also hosted events during the 1987 Rugby World Cup, 1992 Cricket World Cup, 2000 Sydney Olympics, the 2003 Rugby World Cup and hosted the Final of the 2008 Rugby League World Cup. In 2005, then Premier Peter Beattie announced plans for Brisbane to bid to host the 2024 Olympic Games,[68] which in August 2008 received in principle Australian Olympic Committee support, including that of the Queensland Premier Anna Bligh and Brisbane Lord Mayor Campbell Newman.[69]

The city's major sporting venues include Brisbane Cricket Ground, Sleeman Centre at Chandler, Suncorp Stadium, Ballymore Stadium and the stadium facilities of the Queensland Sport and Athletics Centre in Nathan. With the closure of the Milton Tennis grounds in 1994, Brisbane lacked a major tennis facility. In 2005, the State Government approved the State Tennis Centre a new A$65 million tennis stadium. The construction was completed in 2008. The Brisbane International is held here from January 2009.

Brisbane has teams in all major interstate competitions, excluding the National Basketball League.

| Sport | Team Name | League | Stadium | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rugby League | Queensland | State of Origin | Suncorp Stadium | [70] |

| Brisbane Broncos | National Rugby League | [71] | ||

| Rugby Union | Queensland Reds | Super 14 | [72] | |

| Association football | Brisbane Roar | A-League | [73] | |

| Cricket | Queensland Bulls | Sheffield Shield Ford Ranger One Day Cup KFC Twenty20 Big Bash |

The Gabba | [74] |

| Australian rules football | Brisbane Lions | Australian Football League | [75] | |

| Netball | Queensland Firebirds | ANZ Championship | Chandler Arena | [76] |

Media

The main newspapers of Brisbane are The Courier-Mail and The Sunday Mail, both owned by News Corporation. Brisbane receives the national daily, The Australian, and the Weekend Australian, together with Fairfax papers Australian Financial Review, the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, and Fairfax website Brisbane Times. There are community and suburban newspapers throughout the metropolitan and regional areas, including Brisbane News and City News, many of which are produced by Quest Community Newspapers. mX, a free daily commuter newspaper, was launched in 2007, following the newspaper's success in Melbourne and Sydney.

Brisbane is served by all five major television networks in Australia, which broadcast from the summit of Mount Coot-tha. The three commercial stations, Seven, Nine, and Ten, are accompanied by two government networks, ABC and SBS, with all five providing digital television. 31, a community station, also broadcasts in Brisbane. Optus, Foxtel and Austar all operate PayTV services in Brisbane, via cable and satellite means.

The ABC transmits all five of its radio networks to Brisbane; 612 ABC Brisbane, ABC Classic FM, ABC NewsRadio, Radio National, and Triple J. SBS broadcasts its national radio network. Brisbane is serviced by major commercial radio stations, including 4KQ, 4BC, 4BH, 97.3 FM, B105 FM, Nova 106.9, and Triple M. Brisbane is also serviced by major community radio stations such as 96five Family FM, 4MBS Classic FM 103.7, 4EB FM and 4ZZZ 102.1.

Bris Vegas

"Bris Vegas" is a nickname given to the city. This has been attributed to an Elvis Presley tribute CD[77] and the city's growing live music scene.[78] It is believed to have been first used in print in a 1996 edition of The Courier-Mail,[77] also approximately the time of the opening of the Treasury Casino in Brisbane and the popularisation of poker machines in Brisbane bars and clubs, a play on the popular gaming ground of Las Vegas. The name has also been attributed to the city's nightlife[79], compact size of the central business district and previous lack of sophistication when compared with more populated Australian cities[80][81] and also to Las Vegas.[82]

Infrastructure

Health

Brisbane is covered by Queensland Health's "Northside" and "Southside" health service areas.[83] Within the greater Brisbane area there are 8 major public hospitals, 4 major private hospitals, and smaller public and private facilities. Specialist and general medical practices are located in the CBD, and most suburbs and localities. Private hospitals in Brisbane include Greenslopes Private Hospital, Redlands Private Hospital, Mater Private Hospital, Brisbane Private, Wesley and RBH Private.

Transport

Brisbane has an extensive transportation network within the city, as well as connections to regional centres, interstate and to overseas destinations. The use of urban public transport is still only a small component of total passenger transport, the largest component being travel by private car.[84]

Public transport is provided by bus, rail and ferry services. Bus services are operated by public and private operators whereas trains and ferries are operated by public agencies. The Brisbane central business district (CBD) is the central hub for all public transport services with services focusing on Queen Street Bus Station, Roma Street and Central railway stations, and various city ferries wharves. Brisbane's CityCat high speed ferry service, popular with tourists and commuters, operates services along the Brisbane River between the University of Queensland and Apollo Road.

The Citytrain urban rail network consists of 10 suburban lines and covers mostly the west, north and east sides of the city. It also provides the route for an Airtrain service under joint public/private control between the City and Brisbane Airport. Since 2000, Brisbane has been developing a network of busways, including the South East Busway and the Inner Northern Busway, to provide faster bus services. "TransLink", an integrated ticketing system operates across the public transport network.

The Brisbane River has created a barrier to some road transport routes. In total there are ten road bridges, mostly concentrated in the inner city area. This has intensified the need for transport routes to focus on the inner city. There are also three railway bridges and two pedestrian bridges. The Eleanor Schonell Bridge (originally named, and still generally known as, The Green Bridge) between the University of Queensland and Dutton Park is for use by buses, pedestrians and cyclists. There are currently multiple tunnel and bridge projects underway as part of the TransApex plan.

An extensive network of pedestrian and cyclist pathways have been created along the banks of the Brisbane River to form a Riverwalk network.[85]

Brisbane is served by several freeways. The Pacific Motorway connects the central city with the Gold Coast to the south. The Ipswich Motorway connects the city with Ipswich to the west via the southern suburbs, while the Western Freeway and the Centenary Freeway provide a connection between Brisbane's inner-west and the outer south-west, connecting with the Ipswich Motorway south of the Brisbane River. The Bruce Highway is Brisbane's main route north of the city to the rest of the State. The Bruce Highway terminates 1,700 km (1,056 mi) away in Cairns and passes through most major cities along the Queensland coast. The Gateway Motorway is a private toll road which connects the Gold Coast and Sunshine Coasts by providing an alternate route via the Gateway Bridge avoiding Brisbane's inner city area. The Port of Brisbane Motorway links the Gateway to the Port of Brisbane, while Inner City Bypass and the Riverside Expressway act as the inner ring freeway system to prevent motorists from travelling through the city's congested centre.[86]

Brisbane's population growth placed strains on South East Queensland's transport system. The State Government and Brisbane City Council have responded with infrastructure plans and increased funding for transportation projects, such as the South East Queensland Infrastructure Plan and Program. Most of the focus has been placed on expanding current road infrastructure, particularly tunnels and bypasses, as well as improving the public transport system.

Brisbane Airport (IATA code: BNE) is the city's main airport, the third busiest in Australia after Sydney Airport and Melbourne Airport. It is located north-east of the city centre and provides domestic and international passenger services. In the 2008-2009 year, Brisbane Airport handled over 18.5 million passengers. The airport is serviced by the Brisbane Airtrain which provides a rail service from Brisbane's city centre to and from the airport. Archerfield Airport (in Brisbane's southern suburbs) acts as a general aviation airport.

Utilities

Water storage, treatment and delivery for Brisbane is handled by SEQ Water, which sells on to Queensland Urban Utilities (previously Brisbane Water) for distribution to the greater Brisbane area. Water for the area is stored in one of three dams; Wivenhoe, Somerset and North Pine. As of 13 May 2005, Brisbane has enforced water restrictions due to drought.[87] This has also led to the State Government announcing that recycled sewage will be pumped into the dams once the pipeline is complete in 2009.[88]

Electricity and gas grids in Brisbane are handled by Energex (electricity), and Origin Energy (gas), with each company previously holding a monopoly on domestic retail supply. Since 1 July 2007 Queensland regulation changes have opened up the retail energy market, allowing multiple companies to resell both gas and electricity.[89]

Metropolitan Brisbane is serviced by all major and most minor telecommunications companies and their networks. Brisbane has the largest number of enabled DSL telephone exchanges in Queensland. An increasing number are also enabled with special hardware (DSLAMs) which enable high speed ADSL2+ internet access. The Brisbane CBD also features a complete underground fibre optics network, with numerous connections to the inner suburbs provided by various service providers.

Telstra and Optus provide both high speed internet as well as Pay TV through their cable services for the bulk of the city's metropolitan area. Both of these providers also host wireless networks with hotspots within both the inner and suburban areas. In addition, 3 Mobile, Telstra, Optus and Vodafone all operate both 2.5G, 3G and 3.5G mobile phone networks citywide.[90]

Sister cities

Brisbane has sister city relations with the following cities:[91]

Kobe, Japan (1985)

Kobe, Japan (1985) Auckland, New Zealand (1988)

Auckland, New Zealand (1988) Shenzhen, China (1992)

Shenzhen, China (1992) Semarang, Indonesia (1993)

Semarang, Indonesia (1993) Kaohsiung, Taiwan (1997)

Kaohsiung, Taiwan (1997) Daejon, Republic of Korea (2002)

Daejon, Republic of Korea (2002) Chongqing, China (2005)

Chongqing, China (2005) Abu Dhabi, UAE (2009)

Abu Dhabi, UAE (2009)

See also

- Brisbane-related articles

- South East Queensland

References

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009-04-23). [http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/3218.0~2008-09~Main+Features~Main+Features?OpenDocument 08~Main+Features~Main+Features?OpenDocument "3218.0 - Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2007-08"]. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/3218.0~2008-09~Main+Features~Main+Features?OpenDocument 08~Main+Features~Main+Features?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009-09-16). "1216.0 - Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC), Jul 2009, Queensland". http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/8EA943A639BE6767CA2576320019FDC1/$File/12160_jul%202009_qld%20maps.pdf. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (2010-05-21). "1216.0.55.003 - Australian Statistical Geography Standard: Design of the Statistical Areas Level 4, Capital Cities and Statistical Areas Level 3, May 2010". http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/1216.0.55.003Main%20Features4May%202010?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=1216.0.55.003&issue=May%202010&num=&view=. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008-03-17). "Explore Your City Through the 2006 Census Social Atlas Series". http://abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/4a256353001af3ed4b2562bb00121564/45b3371f4a681356ca25740e007c92bf!OpenDocument. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Community Profile Series : Brisbane (Statistical Division)". 2006 Census of Population and Housing. http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ProductSelect?newproducttype=Community+Profiles&collection=Census&period=2006&areacode=305&breadcrumb=LP¤taction=201&action=401. Retrieved 2008-01-21. Map

- ↑ Macquarie ABC Dictionary. The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd. 2003. p. 121. ISBN 0 876429 37 2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 1

- ↑ http://www.transport.qld.gov.au/resources/file/ebd16a04bf3f712/Pdf_retina_report_0410_p3.pdf

- ↑ Beaverstock, J.V.; Smith, R.G.; Taylor, P.J.. "The World According to GaWC 2008". Globalization and World Cities. http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2008t.html.

- ↑ "Tom Petrie's Early Reminiscences of Early Queensland". http://www.seqhistory.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=95%3Apart1chpt1&catid=42%3Atom-petrie&Itemid=67&limitstart=4. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ "Redcliffe". Travel (The Sydney Morning Herald). 8 February 2004. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2005/02/17/1108500203689.html. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ "John Oxley Governor Report". http://www.seqhistory.com/john-oxley/139-john-oxley-1823-governorreport?start=2. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Potter, Ron. "Place Names of South East Queensland". Piula Publications. http://www.dovenetq.net.au/~piula/Placenames/page55.html. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ↑ compiled by Royal Automobile Club of Queensland. (1980). Seeing South-East Queensland (2 ed.). RACQ. pp. 7. ISBN 0-909518-07-6.

- ↑ "About Redcliffe". Redcliffe City Council. http://www.redcliffe.qld.gov.au/about_us.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ↑ Lybaek, Lena; Konrad Raiser, Stefanie Schardien (2004). Gemeinschaft der Kirchen und gesellschaftliche Verantwortung. Münster: LIT. pp. 114. ISBN 978-3825870614.

- ↑ "Christopher Eipper (1813 - 1894)". Street Signs — And What They Mean. Pelican Waters Shire Council. http://www.pelicanwaters.com/pelicanwaters-streetsigns.php. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ de Strzelecki, Paul Edmond (1845). Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land: Accompanied by a Geological Map, Sections, and Diagrams. London, United Kingdom: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- ↑ Establishing Queensland's borders

- ↑ "Organisation chart". Brisbane City Council. http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/BCC:STANDARD:827799619:pc=PC_95. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ "Jolly, William Alfred (1881 - 1955)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090501b.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ "Brisbane". ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee (Qld) Incorporated. 1998. http://www.anzacday.org.au/education/tff/memorials/queensland.html. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Peter Dunn (2 March 2005). "Hirings Section". Australia @ War. http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/ausarmy/hiringsno1lofc.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ "QM Supply in the Pacific during WWII". Quartermaster Professional Bulletin. Spring 1999. http://www.quartermaster.army.mil/OQMG/professional_bulletin/1999/spring1999/QM%20Supply%20in%20the%20Pacific%20During%20WWII.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Peter Dunn (27 August 2005). "The Battle Of Brisbane — 26 & 27 November 1942". Australia @ War. http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/ozatwar/bob.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Brisbane’s last in but best-dressed, Brooke Falvey, City news, July 11, 2008.

- ↑ She picked me up at a dance one night, Joan and Bill Bentson, Queensland Government.

- ↑ "ACGA Past Games 1982". Commonwealth Games Australia. http://www.commonwealthgames.org.au/Templates/Games_PastGames_1982.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Rebecca Bell. "Expo 88 / Brisbane". OZ Culture. http://www.ozbird.com/oz/OzCulture/expo88/brisbane/default.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Gregory, Helen (2007). Brisbane Then and Now. Wingfield, South Australia: Salamander Books. pp. 60. ISBN 9781741730111.

- ↑ Gunn, Angus M. (1978). Habitat: Human Settlements in an Urban Age. Pergamon Press. pp. 178. ISBN 0080214878.

- ↑ "Timeline for Brisbane River" (PDF). Coastal CRC. http://www.coastal.crc.org.au/pdf/HistoricalCoastlines/App_3_Timeline_BrisbaneRiver.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Campbell Newman, "bmag", 3 November 2009

- ↑ "TimeWalks Brisbane — Windmill". Queensland Government. 24 March 2008. http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/oh/treasures/timewalks/bris/1870/windmill. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ Statham-Drew, Pamela (1990). The Origin of Australia's Capital Cities. Cambridge University Press. pp. 257. ISBN 978-0521408325.

- ↑ Pike, Jeffrey (2002). Australia. Insight. ISBN 978-9812347992.

- ↑ "The Commissariat Stores". http://www.queenslandhistory.org.au/comm.html. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Population Growth Australian Bureau of Statistics - Accessed 28 December 2007

- ↑ "Indicator: HS-06 Population density patterns in major cities". Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Government of Australia. http://www.environment.gov.au/soe/2006/publications/drs/indicator/257/index.html. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ↑ Linacre, Edward; Geerts, Bart (1997). Climates and Weather Explained. London: Routledge. p. 379. ISBN 0-415-12519-7. http://books.google.com/?id=mkZa1KLHCAQC&lpg=PA379&pg=PA379#v=onepage&q=.

- ↑ Daniel Sankey and Tony Moore (19 July 2007). "Coldest day on record for Brisbane". The Brisbane Times. http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/articles/2007/07/19/1184559902397.html. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ "Brisbane residents best water savers in world: Newman". ABC News. http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2007/08/27/2016895.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-19.

- ↑ Cubby, Ben (2009-09-23). "Global warning: Sydney dust storm just the beginning". Brisbane Times (Brisbane). http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/global-warning-sydney-dust-storm-just-the-beginning-20090923-g1fi.html. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ↑ Brisbane on alert as dust storms sweep east

- ↑ "Brisbane". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_040913_All.shtml. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ↑ "Brisbane City Council". NetCat. http://www.netcat.com.au/NETCAT/STANDARD/PC_4.html. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ "Annual Report and Financial Statements". Brisbane City Council. http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/BCC:STANDARD:1658601192:pc=PC_1297. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ Department of Tourism, Regional Development and Industry (14 December 2007). "Brisbane's business visitors drive $412 million domestic tourism increase". Brisbane Marketing. http://www.brisbanemarketing.com.au/%5Cnews-and-events%5Cnews-article.aspx?id=171. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ "What is the Smart State". Queensland Government. http://www.smartstate.qld.gov.au/strategy/index.shtm#what. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ Peter Beattie (4 December 2007). "Brain power drives Smart State". The Courier Mail. News.com.au. http://www.news.com.au/couriermail/story/0,23739,22867846-27197,00.html. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ "Brisbane business visitor numbers skyrocket". Brisbane Marketing Convention Bureau. e-Travel Blackboard. 3 January 2008. http://www.etravelblackboard.com/index.asp?id=73027&nav=13. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ "2006 Census QuickStats by Location". Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/PopularAreas?ReadForm&prenavtabname=Popular%20Locations&type=popular&&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&textversion=false&collection=Census&period=2006&producttype=QuickStats&method=&productlabel=&breadcrumb=PL&topic=&. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ↑ "Brisbane Container Terminal, Australia". Port Technology. http://72.14.253.104/search?q=cache:OpXT0QTpjWEJ:www.port-technology.com/projects/brisbane/index.html+http://www.port-technology.com/projects/brisbane/index.html&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=au. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "About Us". Australia TradeCoast. http://www.australiatradecoast.com.au/AboutAustraliaTradeCoast/index.aspx. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ "History". Westfield Group. http://www.westfield.com/corporate/about/history.html. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Community Profile Series : Brisbane (Major Statistical Region)". 2006 Census of Population and Housing. http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ProductSelect?newproducttype=Community+Profiles&collection=Census&period=2006&areacode=31&breadcrumb=LP¤taction=201&action=401. Retrieved 27 December 2009. refer "Basic Community Profile - Brisbane" sheet B10

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 "Growth in Melbourne". 3218.0 - Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2007-08. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 04-23-2009. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/3218.0~2007-08~Main+Features~Victoria?OpenDocument. Retrieved 11-09-2009.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "2006 Census QuickStats: Brisbane (Statistical Division)". 2006 Census QuickStats. http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/LocationSearch?collection=Census&period=2006&areacode=305&producttype=QuickStats&breadcrumb=PL&action=401. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ "3218.0 - Regional Population Growth, Australia, 1996 to 2006". Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3218.0Main%20Features31996%20to%202006?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3218.0&issue=1996%20to%202006&num=&view=#CAPITAL%20CITY%20GROWTH. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ "TAFE Queensland". Queensland Government. http://www.tafe.qld.gov.au/dds/search/browseLocations.do?call_centre_mode=false&externalCallMode=false&breadCrumbsBase=%3Ca+href%3D%22%2F%22+title%3D%22Home%22%3EHome%3C%2Fa%3E&ins_spec=false. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "Education Queensland". Queensland Government. http://education.qld.gov.au/eq/. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "Billboard Loves Brisbane". Music News. Triple J. http://www.abc.net.au/triplej/musicnews/s1838651.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ "Beijing, Berlin among music hot spots in 2007". Music News. Reuters. 1 January 2007. http://www.reuters.com/article/musicNews/idUSN0126189720070102?pageNumber=2&virtualBrandChannel=0&sp=true. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ "History". Brisbane Festival. http://www.brisbanefestival.com.au/history.html. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ↑ "International Market Tourism Facts" (PDF). Tourism Australia. http://www.tourismaustralia.com/content/Research/Factsheets/TopTen_Regions_Dec2006.pdf.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Gregory, Helen (2007). Brisbane Then and Now. Wingfield, South Australia: Salamander Books. pp. 140. ISBN 9781741730111.

- ↑ "Cycling in Brisbane". OurBrisbane. http://www.ourbrisbane.com/activeandhealthy/recreation/cycling/. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ↑ Eleanor Hall (1 April 2005). "Brisbane keen to bid for 2024 Olympics". The World Today. ABC. http://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/content/2005/s1336250.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ Brisbane could host Olympics in 2024

- ↑ "Club Info". National Rugby League. http://www.nrl.com/Clubs/Broncos/tabid/10255/default.aspx. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ "Origin of State Colours Queensland Maroons & NSW Blues". RL1908. http://www.rl1908.com/Origin/colours.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ "Our History". Queensland Rugby Union. http://www.queenslandreds.com.au//qru/qru.rugby/page/62650. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ "History". Brisbane Roar FC. http://www.brisbaneroar.com.au/. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ "Introduction". Queensland Bulls. http://www.qldcricket.com.au/default.asp?PageID=2. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ "All About the Brisbane Lions". Brisbane Lions. http://www.lions.com.au/TheClub/History/BrisbaneLions/tabid/5161/Default.aspx. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ "History of Netball Queensland". Netball Queensland. http://www.netballq.org.au/extra.asp?id=78&OrgID=3. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Tilston, John. Meanjin to Brisvegas: Brisbane Comes of Age. pp. 147–148. ISBN 1-4116-5216-9..

- ↑ "Billboard Backs Brisvegas". The Age. 2007-01-25. http://www.theage.com.au/news/music/billboard-backs-brisvegas/2007/01/25/1169594410115.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap1. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ "City Guide: Brisbane". BBC Sport. 2003-09-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/rugby_union/rugby_world_cup/venues_guide/2982769.stm. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ "QLD: From Brisvegas to Brismanhattan". AAP General News. 2004-09-09. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-98858942.html. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ "Brisbane Residents Embrace City Living". The Age. 2005-11-02. http://www.theage.com.au/news/National/Brisbane-residents-embrace-city-living/2005/11/02/1130823270850.html. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ Amanda Horswill (2007-05-15). "What's in a Name?". The Courier Mail. http://www.news.com.au/couriermail/story/0,23739,21727715-27197,00.html. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ "Profiles — Hospitals". Queensland Health. http://www.health.qld.gov.au/wwwprofiles/default.asp. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ↑ "Year Book Australia, 2005". ABS. http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/d81efef6e2252cf4ca256f7200833049!OpenDocument. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "About RiverWalk". Brisbane City Council. http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/BCC:STANDARD::pc=PC_1217. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ "The upgrade". Gateway Upgrade Project. http://www.gatewayupgradeproject.com.au/asp/index.asp?sid=5&page=upgradeIntro. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ↑ Emma Chalmers, Jeremy Pierce and Neil Hickey (8 February 2008). "Queensland Water Commission retain restrictions". The Courier Mail. news.com.au. http://www.news.com.au/couriermail/story/0,23739,23178059-952,00.html. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ↑ Peter Beattie. "SEQ Will Ave Purified Recycled Water But No Vote: Premier" (Ministerial media statement). Queensland Government. http://statements.cabinet.qld.gov.au/MMS/StatementDisplaySingle.aspx?id=50056. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ "Full Retail Competition". Queensland Department of Mines and Energy. http://www.energy.qld.gov.au/frc.cfm. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ↑ Roland Tellzen (1 April 2008). "Mobile broadband takes off". The Australian. news.com.au. http://www.australianit.news.com.au/story/0,24897,23460734-5013037,00.html. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ↑ "List of Sister Cities". Brisbane City Council. 6 November 2009. http://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/BCC:BASE:1730978129:pc=PC_2707. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

External links

- Brisbane travel guide from Wikitravel

- BRISbites: Suburban Sites (History)

- Our Brisbane - Council administered information site

- City of Brisbane

- Brisbane street map

- Official tourism website of Brisbane

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||