Outlaw

An outlaw or bandit is a person living the lifestyle of outlawry; the word literally means "outside the law".[1]

In the common law of England, a "Writ of Outlawry" made the pronouncement Caput gerat lupinum ("Let his be a wolf's head," literally "May he bear a wolfish head") with respect to its subject, using "head" to refer to the entire person (cf. "per capita") and equating that person with a wolf in the eyes of the law: Not only was the subject deprived of all legal rights of the law being "out"side of the "law", but others could kill him on sight as if he was a wolf or other wild animal. Outlawry was thus one of the harshest penalties in the legal system, since the outlaw had only himself to protect himself, but it also required no enforcement on the part of the justice system. Compare "Outlaw" to Ostracism in Athens, which was a similar concept.

Though the judgment of outlawry is now obsolete (even though it inspired the pro forma Outlawries Bill which is still to this day introduced in the British House of Commons during the State Opening of Parliament), romanticised outlaws became stock characters in several fictional settings. This was particularly so in the United States, where outlaws were popular subjects of newspaper coverage and stories in the 19th century, and 20th century fiction and Western movies. Thus, "outlaw" is still commonly used to mean those violating the law[2] or, by extension, those living that lifestyle, whether actual criminals evading the law or those merely opposed to "law-and-order" notions of conformity and authority (such as the "outlaw country" music movement in the 1970s).

The term "bandit" is now largely considered to be part of the English slang lexicon.

A feature of older legal systems

Ancient Rome

Among other forms of exile, Roman law included the penalty of interdicere aquae et ignis ("to forbid fire and water"). People so penalized were required to leave Roman territory and forefeit their property. If they returned, they were effectively outlaws; providing them the use of fire or water was illegal, and they could be killed at will without legal penalty.[3]

Interdicere aquae et ignis was traditionally imposed by the tribune of the plebs, and is attested to have been in use during the First Punic War of the third century BCE by Cato the Elder.[4] It was later also applied by many other officials, such as the Senate, magistrates,[5], and Julius Caesar as a general and provincial governor during the Gallic Wars.[6] It fell out of use during the early Empire. [7]

In the UK

In English common law, an outlaw was a person who had defied the laws of the realm, by such acts as ignoring a summons to court, or fleeing instead of appearing to plead when charged with a crime. In the earlier law of Anglo-Saxon England, outlawry was also declared when a person committed a homicide and could not pay the weregild, the blood-money, that was due to the victim's kin.

Criminal

The term Outlawry referred to the formal procedure of declaring someone an outlaw, i.e. putting him outside of the sphere of legal protection. In the common law of England, a judgment of (criminal) outlawry was one of the harshest penalties in the legal system, since the outlaw could not use the legal system to protect them if needed, e.g. from mob justice. To be declared an outlaw was to suffer a form of civil or social[8] death. The outlaw was debarred from all civilized society. No one was allowed to give him food, shelter, or any other sort of support – to do so was to commit the crime of aiding and abetting, and to be in danger of the ban oneself. In effect, (criminal) outlaws were criminals on the run who were "wanted dead or alive".

An outlaw might be killed with impunity; and it was not only lawful but meritorious to kill a thief flying from justice — to do so was not murder. A man who slew a thief was expected to declare the fact without delay, otherwise the dead man’s kindred might clear his name by their oath and require the slayer to pay weregild as for a true man[9]. Because the outlaw has defied civil society, that society was quit of any obligations to the outlaw — outlaws had no civil rights, could not sue in any court on any cause of action, though they were themselves personally liable.

By the rules of common law, a criminal outlaw did not need to be guilty of the crime he was outlawed for. If a man was accused of a crime and, instead of appearing in court and defending himself from accusations, fled from justice, he was committing serious contempt of court which was itself a capital crime; so even if he were innocent of the crime he was originally accused of, he was guilty of evading justice.

In the context of criminal law, outlawry faded not so much by legal changes as by the greater population density of the country, which made it harder for wanted fugitives to evade capture; and by the international adoption of extradition pacts.

The Third Reich made extensive use of the concept.[10] Prior to the Nuremberg Trials, the British jurist Lord Chancellor Lord Simon attempted to resurrect the concept of outlawry in order to provide for summary executions of captured Nazi war criminals. Although Simon's point of view was supported by Winston Churchill, American and Soviet attorneys insisted on a trial, and he was thus overruled.

Civil

There was also civil outlawry. Civil outlawry did not carry capital punishment with it, and it was imposed on defendants who fled or evaded justice when sued for civil actions like debts or torts. The punishments for civil outlawry were nevertheless harsh, including confiscation of chattels (movable property) left behind by the outlaw.

In the civil context, outlawry became obsolescent in civil procedure by reforms that no longer required summoned defendants to appear and plead. Still, the possibility of being declared an outlaw for derelictions of civil duty continued to exist in English law until 1879 and in Scots law until the late 1940s. Since then, failure to find the defendant and serve process is usually interpreted in favour of the plaintiff, and harsh penalties for mere nonappearance (merely presumed flight to escape justice) no longer apply.

In other countries

Outlawry also existed in other ancient legal codes, such as the ancient Norse and Icelandic legal code. These societies did not have any police force or prisons and criminal sentences were therefore restricted to either fines or outlawry.

Hobsbawm's Bandits

The colloquial sense of an outlaw as bandit or brigand is the subject of a monograph by British author Eric Hobsbawm:[11]. Hobsbawm's book discusses the bandit as a symbol, and mediated idea, and many of the outlaws he refers to, such as Ned Kelly, Mr. Dick Turpin, and Billy the Kid, are also listed below. According to Hobsbawm

The point about social bandits is that they are peasant outlaws whom the lord and state regard as criminals, but who remain within peasant society, and are considered by their people as heroes, as champions, avengers, fighters for justice, perhaps even leaders of liberation, and in any case as men to be admired, helped and supported. This relation between the ordinary peasant and the rebel, outlaw and robber is what makes social banditry interesting and significant ... Social banditry of this kind is one of the most universal social phenomena known to history.

Famous outlaws

The stereotype owes a great deal to English folklore precedents, in the tales of Robin Hood and of gallant highwaymen. But outlawry was once a term of art in the law, and one of the harshest judgments that could be pronounced on anyone's head.

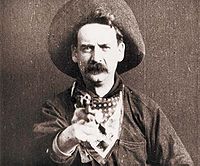

The outlaw is familiar to contemporary readers as an archetype in Western movies, depicting the lawless expansionism period of the United States in the late 19th century. The Western outlaw is typically a criminal who operates from a base in the wilderness, and opposes, attacks or disrupts the fragile institutions of new settlements. By the time of the Western frontier, many jurisdictions had abolished the process of outlawry, and the term was used in its more popular meaning.

American Western

- Big Nose George

- Joaquin Murietta

- Tom Bell

- The Sundance Kid

- William Quantrill

- Jim Miller

- Sam Bass

- Kid Curry

- Butch Cassidy

- Billy the Kid

- John Wesley Hardin

- Jesse James

- Frank James

- Cole Younger

- Belle Starr

- Black Jack

- Black Bart

- John Daly

- Tiburcio Vasquez

- Reno Gang

- Rufus Buck Gang

- Dalton Gang

- The Clantons

Argentinian

- Juan Bautista Bailoretto

- Mate Cocido (Segundo David Peralta)

Australian

In Australia two gangs of bushrangers have been made outlaws – that is they were declared to have no legal rights and anybody was empowered to shoot them without the need for an arrest followed by a trial.

- Ben Hall – the New South Wales colonial government passed a law in 1865 which outlawed the gang (Hall, John Gilbert and John Dunn) and made it possible for anyone to shoot them. There was no need for the outlaws to be arrested and for there to be a trial — the law was essentially a bill of attainder.[12]

- Ned Kelly – The Victorian colonial government passed a law on 30 October 1878 to make the Kelly gang outlaws: they no longer had any legal rights and they could be shot by anyone. The law was modelled on the 1865 legislation passed against the gang of Ben Hall. As well as Ned Kelly, his brother Dan Kelly was subject to the warrant as well as Joe Byrne and Steve Hart.[13]

Brazilian

Cangaceiros

- Lampião – Brazilian outlaw who led the Cangaços, a band of feared marauders and outlaws who terrorized Northeastern Brazil during the 1920 – 1930's.

British

- Hereward the Wake – Saxon outlaw during the Norman conquest of England

- John Nevison – 17th century highwayman[14]

- James MacLaine – Scottish highwayman

- William Plunkett – English highwayman

- Tom King – fictional English highwayman

- Sawney Beane – Scottish outlaw

- Edgar the Outlaw – English king

- Robin Hood – Legendary Medieval English outlaw

- Eustace Folville – English outlaw and soldier

- Adam the Leper – Fourteenth-century English gang-leader

- Rob Roy – Scottish Chieftain.

- Twm Siôn Cati – Welsh Outlaw from Tregaron in Tudor times, ended up mayor of Brecon

- James Hind – 17th century highwayman

- John Clavell – English highwayman, author, and lawyer

- Claude Duval – French-born highwayman in England

- John Wilkes – 18th century English politician

Canadian

- Simon Gunanoot

- Slumach

- Bill Miner

- Ken Leishman – In 1966 he managed to hijack $383,497 worth of gold from the Winnipeg International Airport, amounting to the largest gold heist in Canadian history.

Croatian

Hajduci

- Mijat Tomić

- Andrijica Šimić

East Asian

- Song Jiang – Historical Chinese outlaw immortalised in the classic Water Margin

- Zhang Xianzhong – nicknamed Yellow Tiger, was a Chinese bandit and rebel leader who conquered Sichuan Province in the middle of the 17th century.

- Lao Pie-fang – known as Hun-hutze (red beard), was a bandit chieftain in western Liaoning.

- Wang Delin – bandit, soldier and leader of the National Salvation Army resisting the Japanese pacification of Manchukuo.

- Hong Gildong – Fictitious Korean outlaw

- Ishikawa Goemon – Legendary Japanese thief featured in kabuki plays

- Nezumi Kozō – Japanese thief

- Saigō Takamori – the last true Samurai, he led the Satsuma Rebellion

France

- Louis Dominique Bourguignon, also known as Cartouche

German

- Eppelein von Gailingen

- Frederick of Isenberg

- Hannikel

- Johannes Bückler, nicknamed Schinderhannes

- Matthias Klostermayr, aka Bavarian Hiasl, aka Hiasl of Bavaria, aka der Bayerische Hiasl, aka da Boarische Hiasl

- Mathias Kneißl

- Hans Kohlhase

- Martin Luther was outlawed in 1521 by the Edict of Worms[15]

- Schinderhannes

Greek

Klephtes

- Odysseas Androutsos

- Markos Botsaris

- Athanasios Diakos

- Geórgios Karaïskákis

- Theodoros Kolokotronis

- Nikitaras

Hungarian

- Rózsa Sándor (the most famous Hungarian highwayman)

Icelandic

- Gísli Súrsson

- Grettir Ásmundarson

Irish

- Grace O'Malley

- Redmond O'Hanlon

- Neesy O'Haughan

- Tiger Roche

- Captain Gallagher

- Sean Kelly

Italian

- Carmine Crocco (1830–1905) – Italian bandit and folk hero

- Salvatore Giuliano (1922–1950) – Sicilian bandit and separatist

- Giuseppe Musolino (1876–1956) – Calabrian outlaw and folk hero

- Nicola Napolitano (1838–1863) – Neapolitan bandit

- Gaspare Pisciotta (1924–1954) – Sicilian bandit and separatist

- Francesco Paolo Varsallona – notorious Sicilian bandit leader

Mexican

- Doroteo Arango Arambula – Better known as Pancho Villa, a general in the Mexican Revolution

- Jesus Salgado – led an agrarian revolt in the state of Guerrero during the Mexican Revolution

- Heraclio Bernal, also known as the "Thunderbolt of Sinaloa"

Middle Eastern and Indian

- Simko Shikak – Kurdish bandit and rebel leader[16]

- Dulla Bhatti – was a Punjabi who led a rebellion against the Mughal emperor Akbar. His act of helping a poor peasant's daughter to get married led to a famous folk take which is still recited every year on the festival of Lohri by Punjabis.

- Veerappan, South India's most famous bandit, Elephant poacher, sandalwood smuggler

- Phoolan Devi – one of India's most famous dacoits ("armed robber").[17]

- Shiv Kumar Patel – led one of the few remaining bands of outlaws that have roamed central India for centuries.[18]

- Hashshashin – militant Ismaili Muslim sect, active from the 8th to the 14th centuries.

- Thuggee – Indian network of secret fraternities engaged in murdering and robbing travellers.[19]

Norwegian

Panamanian

- Derienni

Russian

- Nightingale the Robber – myth

- Yermak Timofeyevich – 16th century Cossack outlaw and explorer

- Stenka Razin – Cossack leader

- Yemelyan Pugachov – pretender to the Russian throne

Serbian

- Jovo Stanisavljevic Caruga, Serb

Spanish

- Diego Corrientes Mateos Andalusian (1757–1781)

- El Guapo Andalusian (born 1546) who is reputed to be the source for part one chapter 22 of Don Quixote by Cervantes.

Turkish

- İnce Memed, a legendary fictional character by Yaşar Kemal

- Atçalı Kel Mehmet Efe, an outlaw who led a local revolt against Ottoman Empire

- Çakırcalı Mehmet Efe, one of the most powerful outlaws of late Ottoman era

Others

- Tadas Blinda, in Lithuania

- Juraj Jánošík, in Slovakia

- Johann Georg Grasel, in Moravia

- Andrij Savka, in Lemkivshchyna; defender of the Lemkos against Polish and Hungarian nobility

Outlawing as political weapon

There have been many instances in military and/or political conflicts throughout History whereby one side declares the other as being "illegal", as was the case with emperor Napoleon whom the Congress of Vienna, in 13 March 1815, declared to be "outside the law". In modern times, the government of the First Spanish Republic, unable to reduce the Cantonalist rebellion centered in Cartagena, Spain, declared the Cartagena fleet to be "piratic", which allowed any nation to prey on it.

Taking the opposite road, some outlaws became political leaders, such as Ethiopia's Kassa Hailu who became Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia.

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ Black's Law Dictionary at 1255 (4th ed. 1951), citing 22 Viner, Abr. 316.

- ↑ Black's Law Dictionary at 1255 (4th ed. 1951), citing Oliveros v. Henderson, 116 S.C. 77, 106 S.E. 855, 859.

- ↑ Berger, Adolf. "Interdicere aqua et igni," in Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law, p. 507

- ↑ Kelly, Gordon P. A history of exile in the Roman republic. Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 28

- ↑ Berger, 507.

- ↑ Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallico, book VI, section XLIV.

- ↑ Berger, 507.

- ↑ Zygmunt Bauman, "Modernity and Holocaust".

- ↑ F. Pollock and F. W. Maitland, The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (1895, 2nd. ed., Cambridge, 1898, reprinted 1968).

- ↑ Shirer,"The Third Reich."

- ↑ Bandits, E J Hobsbawm, pelican 1972

- ↑ "Ben Hall and the outlawed bushrangers". Culture and Recreation Portal. Australian Government. 15 April 2008. http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/benhall. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ Cowie, N. (5 July 2002). "Felons' Apprehension Act (Act 612)". http://www.bailup.com/outlaws.htm. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ BBC Inside Out – Highwaymen

- ↑ Bratcher, Dennis. "The Edict of Worms (1521)". The Voice: Biblical and Theological Resources for Growing Christians. http://www.crivoice.org/creededictworms.html. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ Simko, Bandit Leader, Said to Have Defeated Persian Troops., The New York Times

- ↑ Indian bandits kill 13 villagers, BBC News, October 29, 2004

- ↑ Indian bandit slain in gun battle with police, International Herald Tribune, July 23, 2007

- ↑ BBC – Religion & Ethics – Origins of the word 'thug'