Okra

| Abelmoschus esculentus | |

|---|---|

.jpg) |

|

| Okra flower bud and immature seed pod | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Genus: | Abelmoschus |

| Species: | A. esculentus |

| Binomial name | |

| Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench |

|

|

|

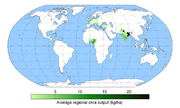

| Worldwide okra production | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Hibiscus esculentus L. |

|

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus Moench, pronounced US: /ˈoʊkrə/, UK: /ˈɒkrə/, known in many English-speaking countries as lady's fingers or gumbo) is a flowering plant in the mallow family. It is valued for its edible green seed pods. Originating in Africa, the plant is cultivated in tropical, subtropical and warm temperate regions around the world.[1]

Contents |

Vernacular names

The name "okra", most often used in the United States and the Philippines, is of West African origin and is cognate with "ọ́kụ̀rụ̀" in Igbo, a language spoken in Nigeria.[2] Okra is often known as lady's fingers outside of the United States.[3] In various Bantu languages, okra is called "kingombo" or a variant thereof, and this is the origin of its name in Portuguese ("quiabo"), Spanish, Dutch and French, and also of the name "gumbo", used in parts of the United States and English-speaking Caribbean for either the vegetable, or a stew based on it[4]. Among Anglophone inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent, it is often called bhindi.

Structure and physiology

The species is an annual or perennial, growing to 2 m tall. It is related to such species as cotton, cocoa, and hibiscus. The leaves are 10–20 cm long and broad, palmately lobed with 5–7 lobes. The flowers are 4–8 cm diameter, with five white to yellow petals, often with a red or purple spot at the base of each petal. The fruit is a capsule up to 18 cm long, containing numerous seeds.

Abelmoschus esculentus is cultivated throughout the tropical and warm temperate regions of the world for its fibrous fruits or pods containing round, white seeds. It is among the most heat- and drought-tolerant vegetable species in the world—but severe frost can damage the pods—and will tolerate poor soils with heavy clay and intermittent moisture.

In cultivation, the seeds are soaked overnight prior to planting to a depth of 1–2 cm. Germination occurs between six days (soaked seeds) and three weeks. Seedlings require ample water. The seed pods rapidly become fibrous and woody and must be harvested within a week of the fruit being pollinated to be edible.[4] The fruits are harvested when immature and eaten as a vegetable.

Origin and distribution

Okra is an allopolyploid of uncertain parentage (proposed parents include Abelmoschus ficulneus, Abelmoschus tuberculatus and a reported "diploid" form of okra). Truly wild, as opposed to naturalised, populations, are not definitely known, and the species may be a cultigen.

The geographical origin of okra is disputed, with supporters of South Asian, Ethiopian and West African origins. Supporters of a South Asian origin point to the presence of its proposed parents in that region. Opposed to this is the lack of a word for okra in the ancient languages of India suggests that it arrived there in the Common Era. Supporters of a West African origin point to the greater diversity of okra in that region; however confusion between Okra and Abelmoschus caillei (West African okra) casts doubt on those analyses.

The Egyptians and Moors of the 12th and 13th centuries used the Arabic word for the plant, suggesting that it had come from the east. The plant may have entered south west Asia across the Red Sea or the Bab-el-Mandeb strait to the Arabian Peninsula, rather than north across the Sahara, or from India. One of the earliest accounts is by a Spanish Moor who visited Egypt in 1216, who described the plant under cultivation by the locals who ate the tender, young pods with meal.[4].

From Arabia, the plant spread around the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and eastward. The plant was introduced to the Americas by ships plying the Atlantic slave trade[5] by 1658, when its presence was recorded in Brazil. It was further documented in Suriname in 1686.

Okra may have been introduced to southeastern North America in the early 18th century. It was being grown as far north as Philadelphia by 1748. Thomas Jefferson noted that it was well established in Virginia by 1781. It was commonplace throughout the southern United States by 1800 and the first mention of different cultivars was in 1806.[4]

Culinary use

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 129 kJ (31 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 7.03 g |

| Sugars | 1.20 g |

| Dietary fiber | 3.2 g |

| Fat | 0.10 g |

| Protein | 2.00 g |

| Water | 90.17 g |

| Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient database |

|

The products of the plant are mucilaginous, resulting in the characteristic "goo" or slime when the seed pods are cooked; the mucilage contains a usable form of soluble fiber. While many people enjoy okra cooked this way, others prefer to minimise sliminess; keeping the pods intact and cooking quickly help to achieve this. To avoid sliminess, okra pods are often briefly stir-fried, or cooked with acidic ingredients such as citrus, tomatoes, or vinegar. A few drops of lemon juice will usually suffice. Alternatively the pods can be sliced thinly and cooked for a long time, so that the mucilage dissolves, as in gumbo. The cooked leaves can also be used as a powerful soup thickener. The immature pods may also be pickled.

In Syria, Egypt, Greece, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Yemen,[6] and other parts of the eastern Mediterranean, including Cyprus and Israel, okra is widely used in a thick stew made with vegetables and meat. It is one of the most popular vegetables among West Asians, North Indians and Pakistanis alike. In most of West Asia, okra is known as bamia or bamya. West Asian cuisine usually uses young okra pods and they are usually cooked whole. In India, the harvesting is done at a later stage, when the pods and seeds are larger.

It is popular in Indian and Pakistan, where chopped pieces are stir fried with spices, pickled, salted or added to gravy-based preparations like Bhindi Ghosht or sambar. In western parts of India (Gujarat, Maharashtra), okra is often stir-fried with some sugar. Okra is also used in Kadhi.

In Caribbean islands, okra is eaten as soup, often with fish. In Haiti it is cooked with rice and maize, and also used as a sauce for meat. It became a popular vegetable in Japanese cuisine toward the end of the 20th century, served with soy sauce and katsuobushi, or as tempura.

Okra forms part of several regional "signature" dishes. Frango com quiabo (chicken with okra) is a Brazilian dish that is especially famous in the region of Minas Gerais. Gumbo, a hearty stew whose key ingredient is okra, is found throughout the Gulf Coast of the United States and in the South Carolina Lowcountry. Breaded, deep fried okra is eaten in the southern United States. Okra is also an ingredient expected in callaloo, a Caribbean dish and the national dish of Trinidad and Tobago. Okra is also eaten in Nigeria, where draw soup is a popular dish, often eaten with garri or cassava. In Vietnam, okra is the important ingredient in the dish canh chua.

Okra leaves may be cooked in a similar way to the greens of beets or dandelions.[7] The leaves are also eaten raw in salads. Okra seeds may be roasted and ground to form a caffeinate-free substitute for coffee.[4] When importation of coffee was disrupted by the American Civil War in 1861, the Austin State Gazette noted, "An acre of okra will produce seed enough to furnish a plantation of fifty negroes with coffee in every way equal to that imported from Rio."[8]

Okra oil is a pressed seed oil, extracted from the seeds of the okra. The greenish-yellow edible oil has a pleasant taste and odor, and is high in unsaturated fats such as oleic acid and linoleic acid.[9] The oil content of the seed can be quite high at about 40%. Oil yields from okra crops are also high. At 794 kg/ha, the yield was exceeded only by that of sunflower oil in one trial.[10] Common Okra seed is reported to contain only 15% oil [11]

Medicinal properties

Unspecified parts of the plant reportedly possess diuretic properties.[12][13]

See also

- Abelmoschus caillei (West African okra)

- Molokhiya, also called "bush okra"

- Luffa, also called "Chinese okra"

References

- ↑ National Research Council (2006-10-27). "Okra". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables. Lost Crops of Africa. 2. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-10333-6. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=11763&page=287. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ McWhorter, John H. (2000). The Missing Spanish Creoles: Recovering the Birth of Plantation Contact Languages. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-21999-6. http://books.google.com/?id=czFufZI4Zx4C&pg=PA77. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ↑ "Alternative Cold Remedies: Lady's Fingers Plant", curing-colds.com (accessed 3 June 2009)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Okra, or 'Gumbo,' from Africa, tamu.edu

- ↑ " Okra gumbo and rice" by Sheila S. Walker, The News Courier, unknown date

- ↑ Julia Devlin and Peter Yee. Trade Logistics in Developing Countries: The Case of the Middle East and North Africa. p. 445

- ↑ Okra Greens and Corn Saute, recipe copyrighted to "c.1996, M.S. Milliken & S. Feniger", hosted by foodnetwork.com

- ↑ Austin State Gazette [TEX.], November 9, 1861, p. 4, c. 2, copied in Confederate Coffee Substitutes: Articles from Civil War Newspapers, University of Texas at Tyler

- ↑ Franklin W. Martin (1982). "Okra, Potential Multiple-Purpose Crop for the Temperate Zones and Tropics". Economic Botany 36: 340–345.

- ↑ Mays, D.A., W. Buchanan, B.N. Bradford, and P.M. Giordano (1990). "Fuel production potential of several agricultural crops". Advances in new crops: 260–263.

- ↑ J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1920, 42 (1), pp 166–170 "Okra Seed Oil"

- ↑ Felter, Harvey Wickes & Lloyd, John Uri. "Hibiscus Esculentus.—Okra.", King's American Dispensatory, 1898, retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Abelmoschus esculentus - (L.)Moench.", Plants for a Future, June 2004, retrieved March 23, 2007.