Berber people

Abd al-Qadir • Idir • Massinissa Guermah

Abd el-Krim • Ferhat Mehenni • Ibrahim Afellay Zinedine Zidane • Moussa Ag Amastan• Tariq ibn Ziyad |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Berber languages, Arabic, French, Spanish (in Morocco and Spain) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Predominantly Islam. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iberians, Egyptians |

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are discontinuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke various Berber languages, which together form a branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. Today many of them speak Darija and also French in the Maghreb, due to the French colonization of the Maghreb, and especially Spanish in Morocco. Today most Berber-speaking people live in Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Tunisia.[1][2]

Many Berbers call themselves some variant of the word Imazighen (singular: Amazigh), possibly meaning "free people" or "free and noble men"[1] (the word has probably an ancient parallel in the Roman name for some of the Berbers, "Mazices").

The best known of the ancient Berbers were the Roman author Apuleius, Saint Augustine of Hippo, and the Roman general Lusius Quietus, who was instrumental in defeating the major Jewish revolt of 115–117. Famous Berbers of the Middle Ages included Tariq ibn Ziyad, a general who conquered Hispania; Abbas Ibn Firnas, a prolific inventor and early pioneer in aviation; Ibn Battuta, a medieval explorer who traveled the longest known distances in pre-modern times; and Estevanico, an early explorer of the Americas. Well-known modern Berbers include Zinedine Zidane, a French-born international football star.

Contents |

Etymology

Because the term Berber appeared for the first time after the end of the Roman Empire, the relevance of its use for the previous period is not accepted by all historians of antiquity.[3]

According to Leo Africanus, Amazigh meant "free men," though this has been disputed, because there is no root of M-Z-Gh meaning "free" in modern Berber languages. It also has a cognate in the Tuareg word "amajegh," meaning "noble".[4][5] This term is common in Morocco, especially among Central-Upper-North Morocco Tamazight and Central-Upper-North-South Morocco Tamazight speakers,[6] but elsewhere within the Berber homeland a local, more particular term, such as Kabyle or Chaoui, is more often used instead.[7] Historically, Berbers have been known by variously terms, for instance, as Meshwesh or Mashewesh by the Egyptians, as the Libyans by the ancient Greeks,[8] as Numidians and Mauri by the Romans, and as Moors by medieval and early modern Europeans. The modern English term, Berber, is probably borrowed from Italian or Arabic, but the deeper etymology of this word is not certain. (See also: Berber (Etymology).) The use of the term Berber spread in the period following the arrival of the Vandals during their major invasions. The history of a Roman consul in Africa made reference for the first time to the term "barbarian" to describe Numidia. Arab historians, some time after, also mentioned the Berbers.[9]

Prehistory

Early inhabitants of the central Maghreb left behind significant remains including remnants of hominid occupation from ca. 200,000 B.C. found near Saïda. Neolithic civilization (marked by animal domestication and subsistence agriculture) developed in the Saharan and Mediterranean Maghrib between 6000 and 2000 B.C. This type of economy, so richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer cave paintings in southeastern Algeria, predominated in the Maghreb until the classical period. The amalgam of peoples of North Africa coalesced eventually into a distinct native population. The Berbers lacked a written language and hence tended to be overlooked or marginalized in historical accounts.

The Berbers have lived in North Africa between western Egypt and the Atlantic Ocean for as far back as records of the area go. Evidence of these early inhabitants of the region are found on the rock art across the Sahara. References to them also occur often in ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sources. Berber groups are first mentioned in writing by the ancient Egyptians during the Predynastic Period, and during the New Kingdom the Egyptians later fought against the Meshwesh and Libu tribes on their western borders. From about 945 BCE the Egyptians were ruled by Meshwesh immigrants who founded the Twenty-second Dynasty under Shoshenq I, beginning a long period of Berber rule in Egypt. They long remained the main population of the Western Desert; the Byzantine chroniclers often complained of the Mazikes (Amazigh) raiding outlying monasteries there.

For many centuries the Berbers inhabited the coast of North Africa from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean. Over time, the coastal regions of North Africa saw a long parade of invaders and colonists including Phoenicians (who founded Carthage), Greeks (mainly in Cyrene, Libya), Romans, Vandals and Alans, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans, and the French and Spanish. Most if not all of these invaders have left some imprint upon the modern Berbers as have slaves brought from throughout Europe (some estimates place the number of European slaves brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period as high as 1.25 million).[10] Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, sub-Saharan Africans, and nomads from East Africa also left impressions upon the Berber peoples.

In historical times, the Berbers expanded south into the Sahara (displacing earlier populations such as the Azer and Bafour), and have in turn been mainly culturally assimilated in much of North Africa by Arabs, particularly following the incursion of the Banu Hilal in the 11th century.

The areas of North Africa which retained the Berber language and traditions have, in general, been the highlands of Kabylie and Morocco, most of which in Roman and Ottoman times remained largely independent, and where the Phoenicians never penetrated far beyond the coast. These areas have been affected by some of the many invasions of North Africa, most recently that of the French.

Some pre-Islamic Berbers were Christians[11] (but evolved their own Donatist doctrine),[12] some were Jewish, and some adhered to their traditional polytheist religion. The best known of them were the Roman author Apuleius and St. Augustine.

History of Berber people in the Maghreb

During the pre-Roman era, several successive independent states (Massylii) existed before the king Massinissa unified the people of Numidia.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches (Botr and Barnès), descended from Mazigh ancestors, who were themselves divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (e.g. Sanhadja, Houaras, Zenata, Masmouda, Kutama, Awarba, Berghwata, etc). All these tribes had independence and territorial decisions.[19][20]

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb, Sudan, Andalusia, Italy, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Egypt, etc. Ibn Khaldun provides a table summarizing the Berber dynasties: Zirid, Banu Ifran, Maghrawa, Almoravid, Hammadid, Almohad, Merinid, Abdalwadid, Wattasid , Meknassa and Hafsid dynasties.[19][21]

They belong to a powerful, formidable, brave and numerous people; a true people like so many others the world has seen - like the Arabs, the Persians, the Greeks and the Romans. The men who belong to this family of peoples have inhabited the Maghreb since the beginning.—Ibn Khaldun, 14th century Arab historian[12]

Numidia

Numidia (202 BC – 46 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in present-day Algeria and part of Tunisia (North Africa) that later alternated between being a Roman province and being a Roman client state, and is no longer in existence today. It was located on the eastern border of modern Algeria, bordered by the Roman province of Mauretania (in modern day Algeria and Morocco) to the west, the Roman province of Africa (modern day Tunisia) to the east, the Mediterranean Sea to the north, and the Sahara Desert to the south. Its people were the Numidians.

The name Numidia was first applied by Polybius and other historians during the third century BC to indicate the territory west of Carthage, including the entire north of Algeria as far as the river Mulucha (Muluya), about 100 miles west of Oran. The Numidians were conceived of as two great tribal groups: the Massylii in eastern Numidia, and the Masaesyli in the west. During the first part of the Second Punic War, the eastern Massylii under their king Gala were allied with Carthage, while the western Masaesyli under king Syphax were allied with Rome. However in 206 BC, the new king of the eastern Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax of the Masaesyli switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa of the Massylii. At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa's territory extended from Mauretania to the boundary of the Carthaginian territory, and also southeast as far as Cyrenaica, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage (Appian, Punica, 106) except towards the sea.

Masinissa was succeeded by his son Micipsa. When Micipsa died in 118, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and Masinissa's illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha, of Berber origin, who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarreled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal. After Jugurtha defeated him in open battle, Adherbal fled to Rome for help. The Roman officials, allegedly due to bribes but perhaps more likely because of a desire to quickly end conflict in a profitable client kingdom, settled the fight by dividing Numidia into two parts. Jugurtha was assigned the western half. However, soon after conflict broke out again, leading to the Jugurthine War between Rome and Numidia.

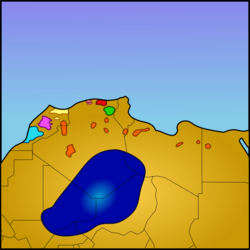

Numidia around 220 BC |

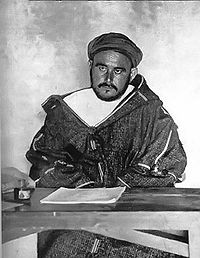

Jugurtha, king of Numidia |

Massinissa famous king of Numidia. Roman era. |

Berbers and the Islamic conquest

Unlike the conquests of previous religions and cultures, the coming of Islam, which was spread by Arabs, was to have pervasive and long-lasting effects on the Maghreb. The new faith, in its various forms, would penetrate nearly all segments of society, bringing with it armies, learned men, and fervent mystics, and in large part replacing tribal practices and loyalties with new social norms and political idioms.

Nonetheless, the Islamization and Arabization of the region were complicated and lengthy processes. Whereas nomadic Berbers were quick to convert and assist the Arab conquerors, not until the 12th century, under the Almohad Dynasty, did the Christian and Jewish communities become marginalized.

The first Arab military expeditions into the Maghrib, between 642 and 669 CE, resulted in the spread of Islam. These early forays from a base in Egypt occurred under local initiative rather than under orders from the central caliphate. But, when the seat of the caliphate moved from Medina to Damascus, the Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty ruling from 661 to 750) recognized that the strategic necessity of dominating the Mediterranean dictated a concerted military effort on the North African front. In 670, therefore, an Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi established the town of Qayrawan about 160 kilometers south of present-day Tunis and used it as a base for further operations.

Abu al Muhajir Dinar, Uqba's successor, pushed westward into Algeria and eventually worked out a modus vivendi with Kusaila, the ruler of an extensive confederation of Christian Berbers. Kusaila, who had been based in Tilimsan (Tlemcen), became a Muslim and moved his headquarters to Takirwan, near Al Qayrawan.

But this harmony was short-lived. Arab and Berber forces controlled the region in turn until 697. By 711, Umayyad forces helped by Berber converts to Islam had conquered all of North Africa. Governors appointed by the Umayyad caliphs ruled from Kairouan, capital of the new wilaya (province) of Ifriqiya, which covered Tripolitania (the western part of present-day Libya), Tunisia, and eastern Algeria.

The spread of Islam among the Berbers did not guarantee their support for the Arab-dominated caliphate due to the discriminatory attitude of the Arabs. The ruling Arabs alienated the Berbers by taxing them heavily; treating converts as second-class Muslims; and, at worst, by enslaving them. As a result, widespread opposition took the form of open revolt in 739-40 under the banner of Kharijite Islam. The Kharijites had been fighting Umayyad rule in the East, and many Berbers were attracted by the sect's seemingly egalitarian precepts.

After the revolt, Kharijites established a number of theocratic tribal kingdoms, most of which had short and troubled histories. But others, like Sijilmasa and Tilimsan, which straddled the principal trade routes, proved more viable and prospered. In 750, the Abbasids, who succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers, moved the caliphate to Baghdad and reestablished caliphal authority in Ifriqiya, appointing Ibrahim ibn al Aghlab as governor in Kairouan. Though nominally serving at the caliph's pleasure, Al Aghlab and his successors, the Aghlabids, ruled independently until 909, presiding over a court that became a center for learning and culture.

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands, Abd ar Rahman ibn Rustam ruled most of the central Maghrib from Tahert, southwest of Algiers. The rulers of the Rustamid imamate, which lasted from 761 to 909, each an Ibadi Kharijite imam, were elected by leading citizens. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice. The court at Tahert was noted for its support of scholarship in mathematics, astronomy, astrology, theology, & law. But the Rustamid imams failed, by choice or by neglect, to organize a reliable standing army. This important factor, accompanied by the dynasty's eventual collapse into decadence, opened the way for Tahert's demise under the assault of the Fatimids.

Berbers in Al-Andalus

The Muslims who invaded Iberia in 711 were mainly Berbers, and were led by a Berber, Tariq ibn Ziyad, though under the suzerainty of the Arab Caliph of Damascus Abd al-Malik and his North African Viceroy, Musa ibn Nusayr. A second mixed army of Arabs and Berbers came in 712 under Ibn Nusayr himself. They supposedly helped the Umayyad caliph Abd ar-Rahman I in Al-Andalus, because his mother was a Berber. During the Taifa era, the petty kings came from a variety of ethnic groups; some—for instance the Zirid kings of Granada--were of Berber origin. The Taifa period ended when a Berber dynasty—the Almoravids from modern-day Morocco --took over Al-Andalus; they were succeeded by the Almohad dynasty from Morocco, during which time al-Andalus flourished.

In the power hierarchy, Berbers were situated between the Arabic aristocracy and the Muladi populace. Ethnic rivalry was one of the most important factors driving Andalusi politics. Berbers made up as much as 20% of the population of the occupied territory.[22]

After the fall of the Caliphate, the taifa kingdoms of Toledo, Badajoz, Málaga and Granada had Berber rulers.

Arabization of Northwest Africa

Before the 9th century, most of Northwest Africa was a Berber-speaking Muslim area. The process of Arabization only became a major factor with the arrival of the Banu Hilal, a tribe sent by the Fatimids of Egypt to punish the Berber Zirid dynasty for having abandoned Shiism. The Banu Hilal reduced the Zirids to a few coastal towns, and took over much of the plains; their influx was a major factor in the Arabization of the region, and in the spread of nomadism in areas where agriculture had previously been dominant.

Soon after the independence in the middle of the 20th century, the countries of North Africa established Arabic as their official language, replacing French (except in Libya), although the shift from French to Arabic for official purposes continues even to this day. As a result, most Berbers had to study and know Arabic, and had no opportunities until the 21st century to use their mother tongue at school or university. This may have accelerated the existing process of Arabization of Berbers, especially in already bilingual areas, such as among the Chaouis.

Berberism had its roots before the independence of these countries, but was limited to some Berber elite. It only began to gain success when North African states replaced the colonial language with Arabic and identified exclusively as Arab nations, downplaying or ignoring the existence and the cultural specificity of Berbers. However, its distribution remains highly uneven. In response to its demands, Morocco and Algeria have both modified their policies, with Algeria redefining itself constitutionally as an "Arab, Berber, Muslim nation".

Now, Berber is a "national" language in Algeria and is taught in some Berber speaking areas as a non-compulsory language. In Morocco, Berber has no official status, but is now taught as a compulsory language regardless of the area or the ethnicity.

Berbers have reached high positions in the social hierarchy; good examples are the former president of Algeria, Liamine Zeroual, and the former prime minister of Morocco, Driss Jettou. In Algeria, furthermore, Chaoui Berbers are over-represented in the Army for historical reasons.

Berberists who openly show their political orientations rarely reach high hierarchical positions. But, Khalida Toumi, a feminist and Berberist militant, has been nominated as head of the Ministry of Communication in Algeria.

A Berber family crossing a ford - scene in Algeria |

Kabyle women |

Young Berber woman, Tunisia 1910 |

Persecution

There are past & present complaints of persecution of Berbers by Arab authorities through both exclusivities: Pan-Arabism and Islamism,[23] their issue of identity is due to the pan-arabist ideology of the former Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, activists: "It is time—long past overdue—to confront the racist arabization of the Amazigh lands."[24]

Modern-day Berbers

Berbers represent the major ethnic origin in North Africa, although up to perhaps a certain extent interbred with other elements (Arab, Subsaharian, Iberian , Punic...), but only about half of the Moroccan population and a third of the Algerian can be identified nowadays as Berber by speaking a Berber language (see there for estimates). Nevertheless, the culture of many Arabic-speaking ethnic groups in these countries is very similar to that of their Berber neighbours and often language may be the only difference between Berbers and Arabs in the Maghreb. Thus, very high estimates of Berber population might include ethnic groups which no longer speak a Berber language. There are also smaller Berber populations in Libya and Tunisia, though exact statistics are unavailable [2] and very small groups in Egypt and Mauritania. Tuareg Berber spread southwards to Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Prominent Berber groups include the Kabyles of northern Algeria, who number about 4 million and have kept, to a large degree, their original language and culture; and the Shilha or Chleuh (French, from Arabic Shalh and Shilha ašəlḥi) of south Morocco, numbering about 8 million. Other groups include the Riffians of north Morocco, the Shawiya language of Algeria, and the Tuareg of the Sahara. There are about 2.2 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians and the Kabyles in the Netherlands, Belgium and France.

Though stereotyped in the West as nomads, most Berbers were in fact traditionally farmers, living in mountains relatively close to the Mediterranean coast, or oasis dwellers; but the Tuareg and Zenaga of the southern Sahara, were nomadic. Some groups, such as the Chaouis, practiced transhumance.

In January 2010, Morocco's Berbers get their own TV channel.[25]

Political tensions have arisen between some Berber groups (especially the Kabyle) and North African governments over the past few decades, partly over linguistic and cultural issues; for instance, in Morocco, giving children Berber names was banned.

Nomadic Berber in Morocco |

Berber shepherd, Morocco |

Berber man in Morocco |

Rachid Kaci, French politician |

|

Mouloud Aounit, French politician |

Berber woman |

Tuareg woman in Mali |

Moroccan Berber in the valley of the Draa river |

Young Berber in typical clothes photographed near Zagora, Morocco |

Tuareg woman from Mali |

Algerian woman of Biskra in traditional clothes, 1917 |

Ahmed Aboutaleb Dutch politician |

Driss Jettou, former Prime Minister of Morocco |

Typical Berber musicians |

Young Riffian boy |

Berber musicians |

Moroccan Berber men at Amazigh Festival in Fes |

Berber warriors during a show in Agadir |

Berber family drinking tea, Atlas Mountains |

Tunisian Berber |

Rifan woman with hat |

Berber children, Atlas Mountains |

History outside the Maghreb

Berbers set up colonies in Mauritania[26] near the Malian imperial capital of Timbuktu.[27]

Diaspora

For historical reasons , Berbers also have emigrated in Europe , notably France , where many Algerian Berbers have emigrated (such as Zinedine Zidane born to Kabyle parents). As well as in Belgium and Netherlands (such as Riffians of Morocco) , in Spain but also in Canada and to a less extent in USA.

Linguistics

The Berber languages form a branch of Afro-Asiatic, and thus descended from the proto-Afro-Asiatic language; on the basis of linguistic migration theory, this is believed by some historical linguists (notably Igor Diakonov and Christopher Ehret) to have originated in northeast Africa no earlier than 12,000 years ago, although Alexander Militarev argues instead for an origin in the Middle East. Ehret specifically suggests identifying the Capsian culture with speakers of languages ancestral to Berber and/or Chadic, and sees the Capsian culture as having been brought there from the African coast of the Red Sea. It is still disputed which branches of Afro-Asiatic are most closely related to Berber, but most linguists accept at least one of Semitic and Chadic as among its closest relatives within the family (see Afro-Asiatic languages.)

There are between 30 and 40 million speakers of Berber languages in North Africa (see population estimation), principally concentrated in Morocco, Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Libya, and with smaller communities as far east as Egypt and as far south as Burkina Faso.

Their dialects, the Berber languages, form a branch of the Afroasiatic linguistic family comprising many closely related varieties, including Riff, Kabyle and Shilha, with a total of roughly 30-40 million speakers. A frequently used generic name for all Berber languages is Tamazight, though this may also be used to refer specifically to Central Morocco Tamazight or Riff.

Ethnic groups

- In Morocco:

- Shilha (Chleuh): Central and Upper-Southern Atlas mountains

- Central Atlas Imazighen: Central and Upper-Northern Atlas mountains

- Riffians: Coastal North Highlands Rif mountains

- In Algeria:

- Chenoui

- Shawiya (Chaoui)

- Kabyle (Zwawa)

- Mozabite

- Tuareg (Tamahaq)

- In Libya:

- Nafusi (Infusen)

- In Egypt:

- Siwi (Isiwiyen), in the Siwa valley of Egypt

- Multiple countries:

- Tuareg

- Zenata

Religions and beliefs

Berbers are mostly Sunni Muslim, while the Mozabites of the Saharan Mozabite Valley are mostly Ibadite. Until the 1960s, there was also an important Jewish Berber community in Morocco,[28] but emigration reduced their number to only a few individuals nowadays. Historically, the small minority of Christian Berbers assimilated into French culture and moved to France after independence (with some pied-noirs being of Berber or part-Berber blood), leaving no more than minuscule numbers in North Africa. However, the Kabyle community in Algeria has decent sized Christian minorities both Protestant and Roman Catholic.

Greek-Berber beliefs

The well-known connections between the ancient Berbers and the ancient Greeks were in Cyrenaica where the Greeks had established colonies. The Greeks influenced the eastern Berber pantheon, but they were also influenced by the Berber culture and beliefs. Generally, the Libyan-Greek relationships knew two different periods. In the first period, the Greeks had peaceful relationships with the Libyans. Later, there existed wars between them. These social relationships were mirrored in their beliefs.

Before the battle of Irassa (570 BC)

The first notable appearance of the Libyan influence on the Cyrenaican-Greek beliefs is the name Cyrenaica itself. This name was originally the name of a legendary (mythic) Berber woman warrior who was known as Cyre. Cyre was ,according to the legend, a courageous lion-hunting woman. She gave her name to the city Cyrene. The emigrating Greeks made her as their protector besides their Greek god Apollo.[29]

The Greeks of Cyrenaica seemed also to have adopted some Berber customs and intermarried with the Berber women. Herodotus (Book IV 120) reported that the Libyans taught the Greeks how to yoke four horses to a chariot. The Cyrenaican Greeks built temples for the Libyan god Amon instead of their original god Zeus. They later identified their supreme god Zeus with the Libyan Amon.[30] Some of them continued worshipping Amon himself. Amon's cult was so widespread among the Greeks that even Alexander the Great decided to be declared as the son of Zeus in the Siwan temple by the Libyan priests of Amon.[31]

The ancient historians mentioned that some Greek deities were of Libyan origin. The daughter of Zeus Athena was considered by some ancient historians, like Herodotus, to have been of Libyan origin. Those ancient historians stated that she was originally honored by the Berbers around Lake Tritonis where she has been born from the god Poseidon and Lake Tritonis, according to the Libyan legend. Herodotus wrote that the Aegis and the clothes of Athena are typical for Libyan woman.

Herodotus stated also that Poseidon (an important Greek sea god) was adopted from the Libyans by the Greeks. He emphasized that no other people worshipped Poseidon from early times than the Libyans who spread his cult:

[..]these I think received their naming from the Pelasgians, except Poseidon; but about this god the Hellenes learnt from the Libyans, for no people except the Libyans have had the name of Poseidon from the first and have paid honour to this god always.[32]

Some other Greek deities were related to Libya. The goddess Lamia was believed to have originated in Libya, like Medusa and the Gorgons. The Greeks seem also to have met the god Triton in Libya. The Greeks may have believed that the Hesperides was situated in modern Morocco. Some scholars situate it in Tangier where Antaios lived, according to some myths. The Hesperides were believed to be the daughters of Atlas a god that is associated with the Atlas mountains by Herodotus. The Atlas mountain was worshipped by the Berbers.

After the Battle of Irassa

.jpg)

The Greeks and the Libyans began to break their harmony in the period of the Battus II.[33] Battus II began secretly to invite other Greek groups to Libya. The Libyans considered that as a danger that has to be stopped. The Berbers began to fight against the Greeks, sometimes in alliance with the Egyptians and other times with the Carthaginians. Nevertheless, the Greeks were the victors. Some historians believe that the myth of Antaios was a reflection of those wars between the Libyans and Greeks.[34] The legend tells that he was the undefeatable protector of the Libyans. He was the son of the god Poseidon and Gaia. He was the husband of the Berber goddess Tinjis. He used to protect the lands of the Berbers until he was slain by the Greek hero Heracles who married Tingis and fathered the son Sufax (Berber-Greek son). Some Libyan kings, like Juba I, claimed to be the descendants of Sufax. While some sources described him as the king of Irassa, Plutarch reported that the Libyans buried Antaios in Tangier:

In this city (Tangier) the Libyans say that Antaeus is buried; and Sertorius had his tomb dug open, the great size of which made him disbelieve the Barbarians...(Plutarch, The Parallel Lives)[35]

In the Greek iconography, Antaeus was clearly distinguished from the Greek appearance. He was depicted with long hair and beard that was typical for the Eastern Libyans.

Important Berbers in Islamic history

Yusuf ibn Tashfin (c. 1061 - 1106) was the Berber Almoravid ruler in North Africa and Al-Andalus (Morrish Iberia). He took the title of amir al-muslimin (commander of the Muslims) after visiting the Caliph of Baghdad 'amir al-moumineen" ("commander of the faithful")and officially receiving his support. He was either a cousin or nephew of Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar, the founder of the Almoravid dynasty. He united all of the Muslim dominions in the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain) to the Kingdom of Morocco (circa 1090), after being called to the Al-Andalus by the Emir of Seville.

Alfonso was defeated on October 23, 1086, at the battle of Sagrajas, at the hands of Yusuf ibn Tashfin, and Abbad III al-Mu'tamid.

Yusuf bin Tashfin is the founder of the famous Moroccan city Marrakech (in Berber Murakush, corrupted to Morocco in English). He himself chose the place where it was built in 1070 and later made it the capital of his Empire. Until then the Almoravids had been desert nomads, but the new capital marked their settling into a more urban way of life.

Abu Abd Allah Muhammad Ibn Tumart (c. 1080 - c. 1130), was a Berber religious teacher and leader from the Masmuda tribe who spiritually founded the Almohad dynasty. He is also known as El-Mahdi (المهدي) in reference to his prophesied redeeming. In 1125 he began open revolt against Almoravid rule. The name "Ibn Tumart" comes from the Berber language and means "son of the earth."[36]

Tariq ibn Ziyad (died 720), known in Spanish history and legend as Taric el Tuerto (Taric the one-eyed), was a Berber Muslim and Umayyad general who led the conquest of Visigothic Hispania in 711. He is considered to be one of the most important military commanders in Spanish history. He was initially the deputy of Musa ibn Nusair in North Africa, and was sent by his superior to launch the first thrust of an invasion of the Iberian peninsula. Some claim that he was invited to intervene by the heirs of the Visigothic King, Wittiza, in the Visigothic civil war.

On April 29, 711, the armies of Tariq landed at Gibraltar (the name Gibraltar is derived from the Arabic name Jabal Tariq, which means mountain of Tariq, or the more obvious Gibr Al-Tariq, meaning rock of Tariq). Upon landing, Tariq is said to have burned his ships then made the following speech, well-known in the Muslim world, to his soldiers:

- O People ! There is nowhere to run away! The sea is behind you, and the enemy in front of you: There is nothing for you, by God, except only sincerity and patience. (as recounted by al-Maqqari).

Ibn Battuta (born February 24, 1304; year of death uncertain, possibly 1368 or 1377) was a Berber[37] Sunni Islamic scholar and jurisprudent from the Maliki Madhhab (a school of Fiqh, or Sunni Islamic law), and at times a Qadi or judge. However, he is best known as a traveler and explorer, whose account documents his travels and excursions over a period of almost thirty years, covering some 73,000 miles (117,000 km). These journeys covered almost the entirety of the known Islamic world, extending from present-day West Africa to Pakistan, India, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia and China, a distance readily surpassing that of his predecessor, near-contemporary Marco Polo.

Abu Ya'qub Yusuf (died on July 29, 1184) was the second Almohad caliph. He reigned from 1163 until 1184. He had the Giralda in Seville built.

Abu Yaqub al-Mustansir Yusuf Caliph of Morocco from 1213 until his death. Son of the previous caliph, Muhammad an-Nasir, Yusuf assumed the throne following his father's death, at the age of only 16 years.

Ziri ibn Manad (died 971), founder of the Zirid dynasty in the Maghreb. Ziri ibn Manad was a clan leader of the Berber Sanhaja tribe who, as an ally of the Fatimids, defeated the rebellion of Abu Yazid (943-947). His reward was the governorship of the western provinces, an area that roughly corresponds with modern Algeria north of the Sahara.

Muhammad Awzal was a religious Berber poet. He is considered the most important author of the Shilha literary tradition. He was born around 1670 in the village of al-Qasaba in the region of Sous, Morocco and died in 1748/9 (1162 of the Egira).

Muhammad al-Jazuli From the tribe of Jazulah which was settled in the Sus area of Morocco between the Atlantic Ocean and the Atlas Mountains. He is most famous for compiling the Dala'il al-Khayrat, an extremely popular Muslim prayer book.

Important Berbers in Christian history

Before the arrival of Islam into the region, most Berber groups were Christians, and a number of Berber theologians were important figures in the development of western Christianity. In particular, the Berber Donatus Magnus was the founder of a Christian group known as the Donatists. The 4th century Catholic Church viewed the donatists as heretics and the dispute led to a schism in the Church dividing North African Christians.[38]

The Romano-Berber theologian known as Augustine of Hippo (modern Chaoui city of Annaba, Algeria), who is recognized as a saint and a Doctor of the Church by Roman Catholicism and the Anglican Communion, was an outspoken opponent of Donatism.[39]

| “ | Of all the fathers of the church, St. Augustine was the most admired and the most influential during the Middle Ages... Augustine was an outsider - a native North African whose family was not Roman but Berber... He was a genius - an intellectual giant.[40] | ” |

Many believe that Arius, another early Christian theologian who was deemed a heretic by the Catholic Church, was of Libyan and Berber descent.

Another Berber cleric, Saint Adrian of Canterbury, travelled to England and played a significant role in its early medieval religious history.

Architecture

.jpg) Ait Benhaddou |

Mosque Koutoubia in Marrakech |

The Giralda, built by the Berbers in Andalus |

Torre del Oro, Sevilla; built by the berber dynasty of the Almohads |

Agdal wall, and gardens; Meknes |

Architecture of Bejaia |

Market on the main square of Ghardaïa. |

Tombs

Medghasen's tomb |

Tomb of Massinissa |

The Medracen Tomb, probably dating to the second century BC, is located near Lambaesis in Algeria[41] |

Berber culture

Traditionally, men take care of livestock. They migrate by following the natural cycle of grazing, and seeking water and shelter. They are thus assured with an abundance of wool, cotton and plants used for dyeing. For their part, women look after the family and handicrafts - first for their personal use, and secondly for sale in the souqs in their locality. The Berber tribes traditionally weave kilims. The tapestry maintains the traditional appearance and distinctiveness of the region of origin of each tribe, which has in effect its own repertoire of drawings. The textile of plain weave is represented by a wide variety of stripes, and more rarely by geometrical patterns such as triangles and diamonds. Additional decorations such as sequins or fringes, are typical of Berber weave in Morocco. The nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyle of the Berbers is very suitable for weaving kilims. The customs and traditions differ from one region to another.[42]

The social structure of the Berbers is tribal. A leader is appointed to command the tribe. In the Middle Ages, many women had the power to govern, such as Kahina and Tazoughert Fatma in Aurès, Tin Hinan in Hoggar, Chemci in Aït Iraten, Fatma Tazoughert in the Aurès. Lalla Fatma N'Soumer was a Berber woman in Kabylia who fought against the French.

The majority of Berber tribes currently have men as heads of the tribe. In Algeria, the el Kseur platform in Kabylia gives tribes the right to fine criminal offenders. In areas of Chaoui, tribal leaders enact sanctions against criminals.[43] The Tuareg have a king who decides the fate of the tribe and is known as Amenokal. It is a very hierarchical society. The Mozabites are governed by the spiritual leaders of Ibadism. The Mozabites lead communal lives. During the crisis of Berriane, the heads of each tribe resolved the problem and began talks to end the crisis between the Maliki and Ibadite movements.[44] In marriages, the man selects the woman, and depending on the tribe, the family often makes the decision. In comparison, in the Tuareg culture, the woman chooses her future husband. The rites of marriage are different for each tribe. Families are either patriarchal or matriarchal, according to the tribe.

Cuisine

Berber cuisine is a traditional cuisine which has evolved little over time. It differs from one area to another within North Africa.

Principal Berber foods are:

- Couscous, a pasta dish

- Tajine, a dish made in various forms

- Pastilla

- bread made with traditional yeast

- "Bouchiar" (fine yeastless wafers soaked in butter and natural honey)

- "Bourjeje" (pancake containing flour, eggs, yeast and salt)

- "Tahricht" (sheep offal: brains, tripe, lungs, and heart): these organ meats are rolled up with the intestines on an oak stick and cooked on embers in specially designed ovens. The meat is coated with butter to make it even tastier. This dish is served mainly at festivities.

Although they are the original inhabitants of North Africa, and in spite of numerous incursions by Phoenicians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans and French, Berbers lived in very contained communities. Having been subject to limited external influences, these populations lived free from acculturating factors.

Some notable Berber dishes

Customized Tajine |

Couscous dish |

Turkey Tajine seasoned with potatoes |

|

.jpg) Tunisian wine |

Algerian wine |

Music

Berber music, the traditional music of North Africa, has a wide variety of regional styles. The best known are the Moroccan music, the popular Kabyle and chawi music of Algeria, and the widespread Tuareg music of Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali.

The instruments used are the bendir (large drums) and Gambra (a lute), which accompanying songs and dances.

Algeria

Traditional Kabylian music consists of vocalists accompanied by a rhythm section, consisting of t'bel (tambourine) and bendir (frame drum), and a melody section, consisting of a ghaita (bagpipe) and ajouag (flute).

Kabylian music has been popular in France since the 1930s, when it was played at cafés. As it evolved, Western string instruments and Arab musical conventions, like large backing orchestras, were added.

By the time raï, a style of Algerian popular music, became popular in France and elsewhere in Europe, Kabylian artists began using less traditional instruments and formats. Hassen Zermani's all-electric Takfarinas and Abdelli's work with Peter Gabriel's Real World helped bring Kabylian music to new audiences, while the murder of Matoub Lounes inspired many Kabylians to rally around their popular musicians.

Morocco

There are three varieties of Berber folk music: village and ritual music, and the music performed by professional musicians. Village music is performed collectively for dancing, including ahidus and ahouach dances. Instruments include flutes and drums. These dances begin with a chanted prayer. Ritual music is performed at regular ceremonies to celebrate marriages and other important life events. Ritual music is also used as protection against evil spirits. Professional musicians (imdyazn) travel in groups of four, led by a poet (amydaz). The amydaz performs improvised poems, often accompanied by drums and rabab (a one-stringed fiddle), along with a bou oughanim who plays a double clarinet and acts as a clown for the group.

The Chleuh Berbers have professional musicians called rwais who play in ensembles consisting of lutes, rababs and cymbals, with any number of vocalist. The leader, or rayes, leads the choreography and music of the group. These performances begin with an instrumental astara on rabab, which also gives the notes of the melody which follows. The next phase is the amarg, or sung poetry, and then ammussu, a danced overture, tammust, an energetic song, aberdag, a dance, and finally the rhythmically swift tabbayt. There is some variation in the presentation of the order, but the astara always begins, and the tabbayt always ends.

Festivals

- Fantasia

- Imilchil Marriage Festival

- Udayn n Acur

Genetics

The population genetics of North Africans has been heavily influenced by geography. The Sahara desert to the south and the Mediterranean Sea to the North were important barriers to gene flow in prehistoric times. However Eurasia and Africa form a single land mass at the Suez. At the Straits of Gibraltar, Africa and Europe are separated by only 15 km (9 mi). At periods of low sea-levels, such as during a glacial maximum, islands that are currently submerged would appear in the Mediterranean and possibly in between the Gibraltar straits. These may have encouraged humans to "island hop" between Africa and Europe. During wetter phases of the Sahara, Sub-Saharan Africans would have expanded into North Africa. West Asian populations would have also been attracted to a wet Sahara. West Asian populations could also migrate into Africa via the coastal regions of the Mediterranean.

As a result of these geographic influences, the genetic profile of Berber populations is a complex mosaic of European, Sub-Saharan African and West Asian influences. Though North Africa has experienced gene-flow from the surrounding regions, it has also experienced long periods of genetic isolation, allowing a distinctive genetic markers to evolve in Berber populations.

Current scientific debate is concerned with determining the relative contributions of different periods of gene flow to the current gene pool of North Africans. Anatomically modern humans are known to have been present in North Africa during the Upper Paleolithic 45,000 years ago as attested by the Aterian culture. With no apparent continuity, 22,000 years ago, the Aterian was succeeded by the Iberomaurusian culture which shared similarities with Iberian cultures. The Iberomaurusian was succeeded by the Capsian, a pre-neolithic culture. About 9,000 years ago the Saharan entered a wet phase which attracted Neolithic peoples from the Near East and Sub-Saharan Africans. In historic times, North Africa was occupied by several peoples including Phoenicians (814–146 BCE), Romans (146 BCE–439 CE), Vandals (439–534 CE),and Byzantines (534–647 CE). In the 7th Century a migration of Bedouin peoples from the Arabian peninsula brought Arabic languages into North Africa.[45]

Y-chromosome

Haplogroup E is the most prevalent haplogroup amongst the Berbers accounting for up to 87% of Y-chromosomes among some Berber populations. Haplogroup E is thought to have emerged in East-Africa and would have later dispersed into North Africa and Eurasia . The major sub-clades of haplogroup E found amongst Berbers belong to E1b1b1 which is believed to have emerged in East Africa. Common subclades include, E1b1b1a, E1b1b1b and E1b1b1*. E1b1b1b is distributed along a west-to-east cline with frequencies which can reach as high as 80% in Northwest Africa. E1b1b1a has been observed at low to moderate frequencies among Berber populations with significantly higher frequencies observed in Northeast Africa relative to Northwest Africa.[46][47]

Eurasian haplogroups such as Haplogroup J and Haplogroup R1 have also been observed at moderate frequencies. A thorough study by Arredi et al. (2004) which analyzed populations from Algeria concludes that the North African pattern of Y-chromosomal variation (including both J1 and E3b2 main haplogroups) is largely of Neolithic origin, which suggests that the Neolithic transition in this part of the world was accompanied by demic diffusion of Berber–speaking pastoralists from the Middle East [46][48] Haplogroup E1a has also been detected at frequencies of 1.6-3.4%. E1a is typically observed in Sub-Saharan populations, however its presence among Berber populations is thought to be ancient as it has been detected in Iberia and among remains of Aboriginals from the Canary Islands. Haplogroup E1b1a has also been observed at low frequencies. E1b1a is most frequent in sub-saharan Africa and is thought to have expanded recently following the adoption of agriculture and Iron-working. It is thus believed to be a recent introduction into the Berber gene-pool.

E1b1b1b (E-M81); formerly E3b1b, E3b2

E1b1b1b (E-M81) is the most common Y chromosome haplogroup in North Africa, dominated by its sub-clade E-M183. It is thought to have originated in North Africa 5,600 years ago. The parent clade E1b1b originated in East Africa.[49][50] Colloquially referred to as the Berber marker for its prevalence among Mozabite, Middle Atlas, Kabylian and other Amazigh groups, E-M81 is also quite common among North African groups. It reaches frequencies of up to 80% in some parts of the Maghreb. This includes the Saharawish for whose men Bosch et al. (2001) reports that approximately 76% are M81+.

This haplogroup is also found of some amounts in the Iberian Peninsula,[51] probably due to ancient migrations during the Islamic, Roman, and Carthaginian empires, as well as the influence of Sephardic Jews.[52] In Iberia generally it is more common than E1b1b1a (E-M78),[53] unlike in the rest of Europe, and as a result this E-M81 is found throughout Latin America[54] and among Hispanic men in USA.[55] As an exceptional case in Europe, this sub-clade of E1b1b1 has also been observed at 40% the Pasiegos from Cantabria.[50]

In smaller numbers, E-M81 men can be found in Sudan, Lebanon, Turkey, and amongst Sephardic Jews.

There are two recognized sub-clades, although one is much more important than the other.

- Sub Clades of E1b1b1b (E-M81):

-

- E1b1b1b1 (E-M107). Underhill et al. (2000) found one example in Mali.

- E1b1b1b2 (E-M183). Individuals with the defining marker for this clade, M81, also test positive, in tests so far, for M183. As of October 23, 2008, the SNP M165 is currently considered to define a subclade, "E1b1b1b2a"[56].

-

Mitochondrial DNA

mtDNA, by contrast, is inherited only from the mother.According to Macaulay et al. 1999, "one-third of Mozabite Berber mtDNAs have a Near Eastern ancestry, probably having arrived in North Africa ∼50,000 years ago, and one-eighth have an origin in sub-Saharan Africa. Europe appears to be the source of many of the remaining sequences, with the rest having arisen either in Europe or in the Near East." [Maca-Meyer et al. 2003] analyze the "autochthonous North African lineage U6" in mtDNA, concluding that:

The most probable origin of the proto-U6 lineage was the Near East. Around 30,000 years ago it spread to North Africa where it represents a signature of regional continuity. Subgroup U6a reflects the first African expansion from the Maghreb returning to the east in Paleolithic times. Derivative clade U6a1 signals a posterior movement from East Africa back to the Maghreb and the Near East. This migration coincides with the probable Afroasiatic linguistic expansion.

A genetic study by Fadhlaoui-Zid et al. 2004[57] argues concerning certain exclusively North African haplotypes that "expansion of this group of lineages took place around 10,500 years ago in North Africa, and spread to neighbouring population", and apparently that a specific Northwestern African haplotype, U6, probably originated in the Near East 30,000 years ago but has not been highly preserved and accounts for 6-8% in southern Moroccan Berbers, 18% in Kabyles and 28% in Mozabites. Rando et al. 1998 (as cited by [3]) "detected female-mediated gene flow from sub-Saharan Africa to NW Africa" amounting to as much as 21.5% of the mtDNA sequences in a sample of NW African populations; the amount varied from 82% (Tuaregs) to 4% (Rifains). This north-south gradient in the sub-Saharan contribution to the gene pool is supported by Esteban et al.[58] Nevertheless, individual Berber communities display a considerably high mtDNA heterogeneity among them. The Berbers of Jerba Island, located in South Eastern Tunisia, display an 87% Eurasian contribution with no U6 haplotypes,[59] while the Kesra of Tunisia, for example, display a much higher proportion of typical sub-Saharan mtDNA haplotypes (49%),[60] as compared to the Zriba (8%). According to the article, "The North African patchy mtDNA landscape has no parallel in other regions of the world and increasing the number of sampled populations has not been accompanied by any substantial increase in our understanding of its phylogeography. Available data up to now rely on sampling small, scattered populations, although they are carefully characterized in terms of their ethnic, linguistic, and historical backgrounds. It is therefore doubtful that this picture truly represents the complex historical demography of the region rather than being just the result of the type of samplings performed so far."

Additionally, recent studies have discovered a close mitochondrial link between Berbers and the Saami of Scandinavia which confirms that the Franco-Cantabrian refuge area of southwestern Europe was the source of late-glacial expansions of hunter-gatherers that repopulated northern Europe after the Last Glacial Maximum and reveals a direct maternal link between those European hunter-gatherer populations and the Berbers.[60][61] With regard to Mozabite Berbers, one-third of Mozabite Berber mtDNAs have a Near Eastern ancestry, probably having arrived in North Africa ∼50,000 years ago, and one-eighth have an origin in sub-Saharan Africa. Europe appears to be the source of many of the remaining sequences, with the rest having arisen either in Europe or in the Near East."[62]

According to the most recent and thorough study about Berber mtDNA from Coudray et al. 2008 that analysed 614 individuals from 10 different regions (Morocco (Asni, Bouhria, Figuig, Souss), Algeria (Mozabites), Tunisia (Chenini-Douiret, Sened, Matmata, Jerba) and Egypt (Siwa))[63] the results may be summarized as follows :

- Total Eurasian lineages (H, HV, R0, J, T, U (without U6), K, N1, N2, X) : 50-90%

- Total sub-Saharan lineages (L0, L1, L2, L3, L4, L5) : 20-50

- Total North African lineages (U6, M1) : 0-30

The Berber mitochondrial pool is characterized by an "overall high frequency of Western Eurasian haplogroups, a somehow lower frequency of sub-Saharan L lineages, and a significant (but differential) presence of North African haplogroups U6 and M1".[64] And according to Cherni et al. 2008 "the post-Last glacial maximum expansion originating in Iberia not only led to the resettlement of Europe but also of North Africa".[65]

Autosomal DNA

Berbers display a heterogeneous autosomal profile but in general autosomal markers are predominantly European or Eurasian with a minor but significant Sub-Saharan African component. As a result, Berber populations possess a genetic profile that is intermediate between Europeans and Sub-Saharan Africans. Analysis of HLA markers has shown that Berbers have a close genetic relationship with Mediterranean Europeans but also possess some characteristics of Sub-Saharan Africans.[66][67]

Genetic influence

Genetic influences on Europe

There are a number of genetic markers which are characteristic of Horn African and North African populations which are to be found in European populations signifying ancient and modern population movements across the Mediterranean. These markers are to be found particularly in Mediterranean Europe but some are also prevalent, at low levels, throughout the continent.

Y-chromosome DNA

The general parent Y-chromosome Haplogroup E1b1b (formerly known as E3b), which originated in either the Horn of Africa[68] or the Near East,[56] is by far the most common clade in North and Northeast Africa, and is also common throughout the majority of Europe, particularly in the Mediterranean and South Eastern Europe. E1b1b reaches its highest concentration in Greece and the Balkan region, but also enjoys a significant presence in other regions such as Hungary, Italy, France, Iberia and Austria. [4].[68]

Outside of North and Northeast Africa, E1b1b's two most prevalent clades are E1b1b1a (E-M78, formerly E3b1a) and E1b1b1b (E-M81, formerly E3b1b).

E1b1b1a is the most common subclade of E1b1b and is present throughout Europe. It was originally thought to have been a marker of Neolithic migrations (perhaps coinciding with the introduction of Agriculture into Europe) from Anatolia to Europe, via the Balkans, where it enjoys the highest frequency. However, Cruciani's latest study suggests that it actually arrived into the Balkans from Western Asia during the Palaeolithic, and then spread throughout Europe much later (circa 5300 years ago) due to a population expansion originating from within the Balkans.

A study from Semino (published 2004) showed that Y-chromosome haplotype E1b1b1b (E-M81), is specific to North African populations and almost absent in Europe except the Iberia (Spain and Portugal) and Sicily.[68] Another 2004 study showed that E1b1b1b is found present, albeit at low levels throughout Southern Europe (ranging from 1.5% in Northern Italians, 2.2% in Central Italians, 1.6% in southern Spaniards, 3.5% in the French, 4% in the Northern Portuguese, 12.2% in the southern Portuguese and 41.2% in the genetic isolate of the Pasiegos from Cantabria).[69] The findings of this latter study contradict a more thorough analysis Y-chromosome analysis of the Iberian peninsula according to which haplogroup E1b1b1b surpasses frequencies of 10% in Southern Spain. The study points only to a very limited influence from northern Africa and the Middle East both in historic and prehistoric times.[70] The absence of microsatellite variation suggests a very recent arrival from North Africa consistent with historical exchanges across the Mediterranean during the period of Islamic expansion, namely of Berber populations.[68] A study restricted to Portugal, concerning Y-chromosome lineages, revealed that "The mtDNA and Y data indicate that the Berber presence in that region dates prior to the Moorish expansion in 711 AD... Our data indicate that male Berbers, unlike sub-Saharan immigrants, constituted a long-lasting and continuous community in the country".[71]

Haplotype V(p49/TaqI), a characteristic North African haplotype, may be also found in the Iberian peninsula, and a decreasing North-South cline of frequency clearly establishes a gene flow from North Africa towards Iberia which is also consistent with Moorish presence in the peninsula.[72] This North-South cline of frequency of halpotype V is to be observed throughout the Mediterranean region, ranging from frequencies of close to 30% in southern Portugal to around 10% in southern France. Similarly, the highest frequency in Italy is to be found in the southern island of Sicily (28%).[73][74]

A wide ranging study (published 2007) using 6,501 unrelated Y-chromosome samples from 81 populations found that: "Considering both these E-M78 sub-haplogroups (E-V12, E-V22, E-V65) and the E-M81 haplogroup, the contribution of northern African lineages to the entire male gene pool of Iberia (barring Pasiegos), continental Italy and Sicily can be estimated as 5.6%, 3.6%, and 6.6%, respectively."[74]

A very recent study about Sicily by Gaetano et al. 2008 found that "The Hg E3b1b-M81, widely diffused in northwestern African populations, is estimated to contribute to the Sicilian gene pool at a rate of 6%." and "confirms the genetic affinity between Sicily and North Africa".[75]

According to the most recent and thorough study about Iberia by Adams et al. 2008 that analysed 1140 unrelated Y-chromosome samples in Iberia, a much more important contribution of northern African lineages to the entire male gene pool of Iberia was found : "mean North African admixture is 10.6%, with wide geographical variation, ranging from zero in Gascony to 21.7% in Northwest Castile".[76][77]

Mitochondrial DNA

Genetic studies on Iberian populations also show that North African mitochondrial DNA sequences (haplogroup U6) and sub-Saharan sequences (Haplogroup L), although present at only low levels, are still at much higher levels than those generally observed elsewhere in Europe.[78][79][80] Haplogroup U6 have also been detected in Sicily and South Italy at very low levels.[81] It happens also to be a characteristic genetic marker of the Saami populations of Northern Scandinavia.[82] It is difficult to ascertain that U6's presence is the consequence of Islam's expansion into Europe during the Middle Ages, particularly because it is more frequent in the north of the Iberian Peninsula rather than in the south. In smaller numbers it is also attested too in the British Isles, again in its northern and western borders. It may be a trace of a prehistoric neolithic/megalithic expansion along the Atlantic coasts from North Africa, perhaps in conjunction with seaborne trade. One subclade of U6 is particularly common among Canarian Spaniards as a result of native Guanche (proto-Berber) ancestry.

Genetic influences on Latin America

As a consequence of Spanish and Portuguese colonization of Latin America, E-M81 is also found throughout Latin America[83][84][85] and among Hispanic men in USA.[86]

See also

- Amazigh Moroccan Democratic Party

- Ancient Libya

- Arabized Berber

- Barbary Coast

- Barbary pirate

- Berber Jews

- Berber languages

- Berber mythology

- Berber pantheon

- Berberism

- Guanches, an indigenous people in the Canary Islands.

- Kabylie, a coastal Berber area, inhabited by Kabyles.

- List of Imazighen

- Masmouda, ancestors of Atlas Chleuhs

- Moors

- Rif, a coastal Berber area, inhabited by Riffis.

- Senhaja, ancestors of Souss Chleuhs.

- Sidi Brahim

- Tamazgha, Berber name for North Africa.

- Tuareg, a Saharan Berber group.

- Zenata, ancestors of Riffis and Chaouis.

References

- Brett, Michael; Fentress, Elizabeth (1997) [ISBN 0-631-16852-4], The Berbers (The Peoples of Africa), ISBN 0-631-20767-8 (Pbk)

- Ehret, Christopher, The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800, ISBN 0813920841

- Celenko, Theodore, ed. (December 1996), Egypt In Africa, Indianapolis Museum of Art, ISBN 978-0253332691

- Cabot-Briggs, L. (2009-10-28), "The Stone Age Races of Northwest Africa", American Anthropologist 58 (3): 584–585, doi:10.1525/aa.1956.58.3.02a00390

- Hiernaux, Jean, The people of Africa, People of the world series, ISBN 0684140403

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 2004

- Encarta, 2005

- Blanc, S. H. (1854), Grammaire de la langue basque (d'apres celle de Larramendi), Lyons & Paris, http://www.archive.org/details/grammairedelala00blangoog

- Cruciani, F; La Fratta, B; Santolamazza; Sellitto; Pascone; Moral; Watson; Guida et al. (May 2004), "Phylogeographic analysis of haplogroup E3b (E-M215) y chromosomes reveals multiple migratory events within and out of Africa.", American journal of human genetics 74 (5): 1014–22, doi:10.1086/386294, ISSN 0002-9297, PMID 15042509

- Entwistle, William J. (1936), The Spanish Language, London, ISBN 0571064043 (as cited in Michael Harrison's work, 1974.)

- Gans, Eric Lawrence (1981), The Origin of Language, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04202-6

- Gèze, Louis (1873) (in French), Eléments de grammaire basque, Beyonne, http://www.archive.org/details/elmentsdegramm00gzuoft

- Hachid, Malika (2001), Les Premiers Berberes, EdiSud, ISBN 2744902276

- Hagan, Helene E. (2001), The Shining Ones: an Etymological Essay on the Amazigh Roots of Ancient Egyptian Civilisation, XLibris, ISBN 978-0-7388-2567-0

- Hagan, Helene E. (2006), Tuareg Jewelry: Traditional Patterns and Symbols, XLibris, ISBN 1425704530

- Harrison, Michael (1974), The Roots of Witchcraft, Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, ISBN 0426158512

- Hoffman, Katherine E., and Susan Gilson Miller, eds. Berbers and Others: Beyond Tribe and Nation in the Maghrib (Indiana University Press; 2010) 225 pages; scholarly studies of identity, creativity, history, and activism

- Hualde, J. I. (1991), Basque Phonology, London & New York: Routledge, ISBN 0415056551

- Martins, J. P. de Oliveira (1930), A History of Iberian Civilization, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0815403003

- Myles, S; Bouzekri; Haverfield; Cherkaoui; Dugoujon; Ward (Jun 2005), "Genetic evidence in support of a shared Eurasian-North African dairying origin.", Human genetics 117 (1): 34–42, doi:10.1007/s00439-005-1266-3, ISSN 0340-6717, PMID 15806398

- Nebel, A; Landau-Tasseron; Filon; Oppenheim; Faerman (Jun 2002), "Genetic evidence for the expansion of Arabian tribes into the Southern Levant and North Africa.", American journal of human genetics 70 (6): 1594–6, doi:10.1086/340669, ISSN 0002-9297, PMID 11992266

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1915-1923), Men of the Old Stone Age, New York, http://www.archive.org/details/menofoldstoneage00osbouoft

- Renan, Ernest (1873) [First published Paris, 1858] (in French), De l'Origine du Langage, Paris: La société berbère

- Ripley, W. Z. (1899), The Races of Europe, New York: D. Appleton & Co.

- Ryan, William; Pitman, Walter (1998), Noah's Flood: The new scientific discoveries about the event that changed history, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0684810522

- Saltarelli, M. (1988), Basque, New York: Croom Helm, ISBN 0709933533

- Semino, O; Magri, PJ; Benuzzi; Lin; Al-Zahery; Battaglia; Maccioni; Triantaphyllidis et al. (May 2004), "Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area.", American journal of human genetics 74 (5): 1023–34, doi:10.1086/386295, ISSN 0002-9297, PMID 15069642

- Silverstein, Paul A. (2004), Algeria in France: Transpolitics, Race, and Nation, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253344514

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Morocco's Berbers Battle to Keep From Losing Their Culture. San Francisco Chronicle. March 16, 2001.

- ↑ Berbers: The Proud Raiders. BBC World Service.

- ↑ Journée d'étude Africa Antiqua sur l'historiographie de l'Afrique du Nord. Voir les remarques de M. Lenoir en fin de compte rendu

- ↑ Brett, M.; Fentress, E.W.B. (1996), The Berbers, Blackwell Publishing, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Maddy-weitzman, B. (2006), "Ethno-politics and globalisation in North Africa: The berber culture movement*" (PDF), The Journal of North African Studies 11 (1): 71–84, doi:10.1080/13629380500409917, http://taylorandfrancis.metapress.com/index/J28P5N4836V252T6.pdf, retrieved 2007-07-17

- ↑ (French) INALCO report on Central Morocco Tamazight: maps, extension, dialectology, name

- ↑ Mohand Akli Haddadou, Le guide de la culture berbère, Paris Méditerranée, 2000, p.13-14

- ↑ Brian M. Fagan, Roland Oliver, Africa in the Iron Age: c 500 BCE to 1400 CE p. 47

- ↑ Ibn Khaldoun, Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale

- ↑ European slaves in North Africa, Washington Times, 10 March 2004

- ↑ The Last Christians Of North-West Africa: Some Lessons For Orthodox Today

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 The Berbers, BBC World Service | The Story of Africa

- ↑ Histoire de l'émigration kabyle en France au XXe siècleréalités culturelles ... De Karina Slimani-Direche

- ↑ Google Books

- ↑ Les cultures du Maghreb De Maria Angels Roque, Paul Balta, Mohammed Arkoun

- ↑ Histoire de l'émigration kabyle en France au XXe siècle réalités culturelles ... De Karina Slimani-Direche

- ↑ Dialogues d'histoire ancienne à l'Université de Besançon, Centre de recherches d'histoire ancienne

- ↑ Les cultures du Maghreb de Maria Angels Roque, Paul Balta et Mohammed Arkoun

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale De Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin

- ↑ Google Books

- ↑ (French) Google Books

- ↑ Spain - Al Andalus, Library of Congress

- ↑ Kabylia.info

- ↑ Kabylia.info

- ↑ Google.com

- ↑ Historical Dictionaries : North Africa

- ↑ Berbers and Blacks: Impressions of Morocco, Timbuktu and Western Sudan, David Prescott Barrows

- ↑ Mondeberbere.com

- ↑ K. Freeman Greek city state- N.Y. 1983, p. 210.

- ↑ Oric Bates, The Eastern Libyans.

- ↑ Mohammed Chafik, revue Tifinagh...

- ↑ Herodotus Book 2: Euterpe 50

- ↑ the word Battus is believed to be originally a Berber word meaning King in the Berber language

- ↑ Oric Bates. The Eastern Libyans, Franc Cass Co. p. 260

- ↑ Plutarch, The Parallel Lives: The Life of Sertorius.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of the Orient - Ibn Tumart

- ↑ Ross E. Dunn, The Adventures of Ibn Battuta - A Muslim Traveler of the 14th Century, University of California, 2004 ISBN 0-520-24385-4.

- ↑ "The Donatist Schism. External History." History of the Christian Church, Volume III: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity. 311-600 CE. [1]

- ↑ Augustine's Letter to the Donatists (Letter 76).

- ↑ Cantor, Norman (1993), The Civilization of the Middle Ages, Harper, p. 74, ISBN 0060925531

- ↑ Montagu Colvin, Howard. Architecture and the After-life. 1991, page 26

- ↑ ABC Amazigh. An editorial experience in Algeria, 1996-2001 experience, Smaïl Medjeber

- ↑ Elwaten, Hassan Moali, 31 August 2008, to honor the tribe

- ↑ Hadj-Brahim nechat-Member-of-Elwaten, Salima Tlemçani, 18 June 2008

- ↑ Rando (1998), "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Northwest African populations reveals genetic exchanges with European, Near-Eastern, and sub-Saharan populations", Annals of Human Genetics, http://pagesperso-orange.fr/bsecher/Articles/Rando.pdf

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Semino et al., O; Magri, C; Benuzzi, G; Lin, AA; Al-Zahery, N; Battaglia, V; MacCioni, L; Triantaphyllidis, C et al. (2004), "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area", American journal of human genetics 74 (5): 1023–34, doi:10.1086/386295, PMID 15069642, PMC 1181965, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1181965/

- ↑ Kujanova, Martina; Pereira, Luísa; Fernandes, VeróNica; Pereira, Joana B.; Černý, Viktor (2009), "Near Eastern Neolithic genetic input in a small oasis of the Egyptian Western Desert", American Journal of Physical Anthropology 140 (2): 336, doi:10.1002/ajpa.21078, PMID 19425100, http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/122377292/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

- ↑ although later papers have suggested that this date could have been as longas ten thousand years ago, with the transition from the Oranian to the Capsian culture in North Africa. SpringerLink - Journal Article

- ↑ Arredi et al. (2004)

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Scozzari, R, Vona, Aman et al. (May 2004), "Phylogeographic analysis of haplogroup E3b (E-M215) y chromosomes reveals multiple migratory events within and out of Africa", Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (5): 1014–22, doi:10.1086/386294, ISSN 0002-9297, PMID 15042509

- ↑ According to Adams et al. (2008) that analysed 1140 unrelated Y-chromosome samples in Iberia : "mean North African admixture is 10.6%, with wide geographical variation, ranging from zero in Gascony to 21.7% in Northwest Castile".

- ↑ Gonçalves et al. (2005)

- ↑ See for example Flores et al. (2004).

- ↑ See the remarks of genetic genealogist Robert Tarín for example. We can add 6.1% (8 out of 132) in Cuba, Mendizabal et al. (2008); 5.4% (6 out of 112) in Brazil (Rio de Janeiro), "The presence of chromosomes of North African origin (E3b1b-M81; Cruciani et al., 2004) can also be explained by a Portuguese-mediated influx, since this haplogroup reaches a frequency of 5.6% in Portugal (Beleza et al., 2006), quite similar to the frequency found in Rio de Janeiro (5.4%) among European contributors.", Silva et al. (2006)

- ↑ 2.4% (7 out of 295) among Hispanic men from California and Hawaii, Paracchini et al. (2003)

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Y-DNA Haplogroup E and its Subclades - 2008

- ↑ Fadhlaoui-Zid K, Plaza S, Calafell F, Ben Amor M, Comas D, Bennamar El gaaied A (May 2004), "Mitochondrial DNA heterogeneity in Tunisian Berbers", Ann. Hum. Genet. 68 (Pt 3): 222–33, doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00096.x, ISSN 0003-4800, PMID 15180702

- ↑ Esteban E, González-Pérez E, Harich N et al. (Mar 2004), "Genetic relationships among Berbers and South Spaniards based on CD4 microsatellite/Alu haplotypes", Ann. Hum. Biol. 31 (2): 202–12, doi:10.1080/03014460310001652275, ISSN 0301-4460, PMID 15204363

- ↑ Loueslati BY, Cherni L, Khodjet-Elkhil H et al. (January 2006), "Islands inside an island: reproductive isolates on Jerba island", Am. J. Hum. Biol. 18 (1): 149–53, doi:10.1002/ajhb.20473, ISSN 1042-0533, PMID 16378336

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Cherni L, Loueslati BY, Pereira L, Ennafaâ H, Amorim A, El Gaaied AB (February 2005), "Female gene pools of Berber and Arab neighboring communities in central Tunisia: microstructure of mtDNA variation in North Africa", Hum. Biol. 77 (1): 61–70, doi:10.1353/hub.2005.0028, ISSN 0018-7143, PMID 16114817

- ↑ Achilli A, A, Semino, Torroni et al. (May 2005), "Saami and Berbers--an unexpected mitochondrial DNA link", Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76 (5): 883–6, doi:10.1086/430073, ISSN 0002-9297, PMID 15791543

- ↑ Macaulay et al. (1999), The Emerging Tree of West Eurasian mtDNAs: A Synthesis of Control-Region Sequences and RFLPs, Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64:232–249, 1999

- ↑ Data from Achilli et al. 2005; Brakez et al. 2001; Cherni et al. 2005; Fadhlaoui-Zid et al. 2004; Krings et al.1999; Loueslati et al. 2006; Macaulay et al. 1999; Olivieri et al. 2006; Plaza et al. 2003; Rando et al. 1998; Stevanovitchet al. 2004; Coudray et al.2008; Cherni et al. 2008

- ↑ Coudray C, Olivieri A, Achilli A et al. (March 2009), "The complex and diversified mitochondrial gene pool of Berber populations", Annals of Human Genetics 73 (2): 196–214, doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00493.x, ISSN 0003-4800, PMID 19053990

- ↑ Cherni L, L, Pereira, Pereira JB et al. (June 2009), "Post-last glacial maximum expansion from Iberia to North Africa revealed by fine characterization of mtDNA H haplogroup in Tunisia", American Journal of Physical Anthropology 139 (2): 253–60, doi:10.1002/ajpa.20979, ISSN 0002-9483, PMID 19090581

- ↑ Piancatelli, D.; Canossi, A.; Aureli, A.; Oumhani, K.; Del Beato, T.; Di Rocco, M.; Liberatore, G.; Tessitore, A. et al. (2004), "Human leukocyte antigen-A, -B, and -Cw polymorphism in a Berber population from North Morocco using sequence-based typing", Tissue Antigens 63 (2): 158, doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00161.x, PMID 14705987, http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118742130/abstract.

- ↑ Hajjej, A.; Kaabi, H.; Sellami, M. H.; Dridi, A.; Jeridi, A.; El Borgi, W.; Cherif, G.; Elgaaied, A. et al. (2006), "The contribution of HLA class I and II alleles and haplotypes to the investigation of the evolutionary history of Tunisians", Tissue Antigens 68 (2): 153, doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00622.x, PMID 16866885, http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118585922/abstract.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 Santachiara-Benerecetti, AS, King, Torroni et al. (May 2004), "Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area", American Journal of Human Genetics 74 (5): 1023–34, doi:10.1086/386295, ISSN 0002-9297, PMID 15069642

- ↑ Cruciani et al., 2004, Phylogeography of the Y-Chromosome Haplogroup E3b

- ↑ Reduced Genetic Structure for Iberian Peninsula: implications for population demography. (2004)

- ↑ Gonçalves R, Freitas A, Branco M et al. (July 2005), "Y-chromosome lineages from Portugal, Madeira and Açores record elements of Sephardim and Berber ancestry", Annals of Human Genetics 69 (Pt 4): 443–54, doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00161.x, ISSN 0003-4800, PMID 15996172

- ↑ Lucotte G, Gérard N, Mercier G (October 2001), "North African genes in Iberia studied by Y-chromosome DNA haplotype 5", Human Biology 73 (5): 763–9, doi:10.1353/hub.2001.0066, ISSN 0018-7143, PMID 11758696

- ↑ Gérard N, Berriche S, Aouizérate A, Diéterlen F, Lucotte G (June 2006), "North African Berber and Arab influences in the western Mediterranean revealed by Y-chromosome DNA haplotypes", Human Biology 78 (3): 307–16, doi:10.1353/hub.2006.0045, ISSN 0018-7143, PMID 17216803, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3659/is_200606/ai_n17175647/

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Brdicka, GD, Scozzari, R, Novelletto et al. (June 2007), "Tracing past human male movements in northern/eastern Africa and western Eurasia: new clues from Y-chromosomal haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12" (Free full text), Molecular Biology and Evolution 24 (6): 1300–11, doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049, ISSN 0737-4038, PMID 17351267, http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17351267

- ↑ Piazza, A, Gasparini, Matullo et al. (January 2009), "Differential Greek and northern African migrations to Sicily are supported by genetic evidence from the Y chromosome", European Journal of Human Genetics 17 (1): 91–9, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.120, ISSN 1018-4813, PMID 18685561, "The co-occurrence of the Berber E3b1b-M81 (2.12%) and of the Mid-Eastern J1-M267 (3.81%) Hgs together with the presence of E3b1a1-V12, E3b1a3-V22, E3b1a4-V65 (5.5%) support the hypothesis of intrusion of North African genes. (...) These Hgs are common in northern Africa and are observed only in Mediterranean Europe and together the presence of the E3b1b-M81 highlights the genetic relationships between northern Africa and Sicily. (...) Hg E3b1b-M81 network cluster confirms the genetic affinity between Sicily and North Africa."

- ↑ Calafell, F, Jobling, MA, Martínez-Jarreta et al. (December 2008), "The genetic legacy of religious diversity and intolerance: paternal lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula", American Journal of Human Genetics 83 (6): 725–36, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007, ISSN 0002-9297, PMID 19061982

- ↑ "The study shows that religious conversions and the subsequent marriages between people of different lineage had a relevant impact on modern populations both in Spain, especially in the Balearic Islands, and in Portugal", The religious conversions of Jews and Muslims have had a profound impact on the population of the Iberian Peninsula, Elena Bosch, 2008

- ↑ Plaza S, Calafell F, Helal A et al. (July 2003), "Joining the pillars of Hercules: mtDNA sequences show multidirectional gene flow in the western Mediterranean", Annals of Human Genetics 67 (Pt 4): 312–28, doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00039.x, ISSN 0003-4800, PMID 12914566, http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0003-4800&date=2003&volume=67&issue=Pt%204&spage=312, "Haplogroup U6 is present at frequencies ranging from 0 to 7% in the various Iberian populations, with an average of 1.8%. Given that the frequency of U6 in NW Africa is 10%, the mtDNA contribution of NW Africa to Iberia can be estimated at 18%. This is larger than the contribution estimated with Y-chromosomal lineages (7%) (Bosch et al. 2001)."

- ↑ Pereira L, Cunha C, Alves C, Amorim A (April 2005), "African female heritage in Iberia: a reassessment of mtDNA lineage distribution in present times", Human Biology 77 (2): 213–29, doi:10.1353/hub.2005.0041, ISSN 0018-7143, PMID 16201138, "Although the absolute value of observed U6 frequency in Iberia is low, it reveals a considerable North African female contribution, if we keep in mind that haplogroup U6 is not very common in North Africa itself and virtually absent in the rest of Europe. Indeed, because the range of variation in western North Africa is 4-28%, the estimated minimum input is 8.54%"

- ↑ González AM, Brehm A, Pérez JA, Maca-Meyer N, Flores C, Cabrera VM (April 2003), "Mitochondrial DNA affinities at the Atlantic fringe of Europe", American Journal of Physical Anthropology 120 (4): 391–404, doi:10.1002/ajpa.10168, ISSN 0002-9483, PMID 12627534, "Our results clearly reinforce, extend, and clarify the preliminary clues of an 'important mtDNA contribution from northwest Africa into the Iberian Peninsula' (Côrte-Real et al., 1996; Rando et al., 1998; Flores et al., 2000a; Rocha et al., 1999)(...) Our own data allow us to make minimal estimates of the maternal African pre-Neolithic, Neolithic, and/or recent slave trade input into Iberia. For the former, we consider only the mean value of the U6 frequency in northern African populations, excluding Saharans, Tuareg, and Mauritanians (16%), as the pre-Neolithic frequency in that area, and the present frequency in the whole Iberian Peninsula (2.3%) as the result of the northwest African gene flow at that time. The value obtained (14%) could be as high as 35% using the data of Corte-Real et al. (1996), or 27% with our north Portugal sample."