Bristol Beaufighter

- Bristol Beaufighter is also the name of a car produced by Bristol Cars in the 1980s.

| Type 156 Beaufighter | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The Beaufighter Mk X with rockets. This machine is NE255/EE-H of No. 404 Squadron RAF, of RAF Coastal Command at Davidstow Moor, 21 August 1944.[1] | |

| Role | Heavy fighter / strike aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Bristol Aeroplane Company |

| First flight | 17 July 1939 |

| Introduction | 27 July 1940 |

| Retired | 1960 (Australia) |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force Royal Canadian Air Force |

| Produced | May 1940–1946 |

| Number built | 5,928 |

| Developed from | Bristol Beaufort |

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter, often referred to as simply the Beau, was a British long-range heavy fighter modification of the Bristol Aeroplane Company's earlier Beaufort torpedo bomber design. The name Beaufighter is a portmanteau of "Beaufort" and "fighter".

Unlike the Beaufort, the Beaufighter had a long career and served in almost all theatres of war in the Second World War, first as a night fighter, then as a fighter bomber and eventually replacing the Beaufort as a torpedo bomber. A variant was built in Australia by the Department of Aircraft Production (DAP) and was known in Australia as the DAP Beaufighter.

Contents |

Design and development

The idea of a fighter development of the Beaufort was suggested to the Air Ministry by Bristol. The suggestion coincided with the delays in the development and production of the Westland Whirlwind cannon-armed twin-engine fighter. Since the "Beaufort Cannon Fighter" was a conversion of an existing design, development and production could be expected far more quickly than with a completely fresh design. Accordingly, the Air Ministry produced Specification F.11/37 written around Bristol's suggestion for an "interim" aircraft pending proper introduction of the Whirlwind. Bristol started building a prototype by taking a part-built Beaufort out of the production line. The prototype first flew on 17 July 1939, a little more than eight months after the design had started, possibly due to the use of much of the Beaufort's design and parts. A production contract for 300 machines had already been placed two weeks before the prototype F.17/39 even flew.

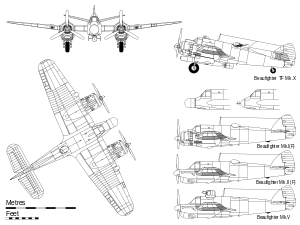

In general, the differences between the Beaufort and Beaufighter were minor. The wings, control surfaces, retractable landing gear and aft section of the fuselage were identical to those of the Beaufort, while the wing centre section was similar apart from certain fittings. The bomb bay was omitted, and four forward-firing 20 mm Hispano Mk III cannons were mounted in the lower fuselage area. These were initially fed from 60-round drums, requiring the radar operator to change the ammunition drums manually — an arduous and unpopular task, especially at night and while chasing a bomber. As a result, they were soon replaced by a belt-feed system. The cannons were supplemented by six .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machineguns in the wings (four starboard, two port). The areas for the rear gunner and bomb-aimer were removed, leaving only the pilot in a fighter-type cockpit. The navigator/radar operator sat to the rear under a small perspex bubble where the Beaufort's dorsal turret had been.

The Bristol Taurus engines of the Beaufort were not powerful enough for a fighter and were replaced by the more powerful Bristol Hercules. The extra power presented problems with vibration; in the final design they were mounted on longer, more flexible struts, which stuck out from the front of the wings. This moved the centre of gravity (CoG) forward, a bad thing for an aircraft design. It was moved back by shortening the nose, as no space was needed for a bomb aimer in a fighter. This put most of the fuselage behind the wing, and moved the CoG back where it should be. With the engine cowlings and propellers now further forward than the tip of the nose, the Beaufighter had a characteristically stubby appearance.

Production of the Beaufort in Australia, and the highly successful use of British-made Beaufighters by the Royal Australian Air Force, led to Beaufighters being built by the Australian Department of Aircraft Production (DAP) from 1944 onwards. The DAP's variant was an attack/torpedo bomber known as the Mark 21: design changes included Hercules VII or XVIII engines and some minor changes in armament.

By the time British production lines shut down in September 1945, 5,564 Beaufighters had been built in England, by Bristol and also by Fairey Aviation Company, (498) Ministry of Aircraft Production (3336) and Rootes (260).

When Australian production ceased in 1946, 365 Mk.21s had been built.[2][3]

Operational service

By fighter standards, the Beaufighter Mk.I was rather heavy and slow. It had an all-up weight of 16,000 lb (7,000 kg) and a maximum speed of only 335 mph (540 km/h) at 16,800 ft (5,000 m). Nevertheless this was all that was available at the time, as further production of the otherwise excellent Westland Whirlwind had already been stopped due to problems with production of its Rolls-Royce Peregrine engines.

The Beaufighter found itself coming off the production line at almost exactly the same time as the first British Airborne Intercept (AI) radar sets. With the four 20 mm cannon mounted in the lower fuselage, the nose could accommodate the radar antennas, and the general roominess of the fuselage enabled the AI equipment to be fitted easily. Even loaded to 20,000 lb (9,100 kg) the plane was fast enough to catch German bombers. By early 1941, it was an effective counter to Luftwaffe night raids. The various early models of the Beaufighter soon commenced service overseas, where its ruggedness and reliability soon made the aircraft popular with crews.

A night-fighter Mk VIF was supplied to squadrons in March 1942, equipped with AI Mark VIII radar. As the faster de Havilland Mosquito took over in the night fighter role in mid to late 1942, the heavier Beaufighters made valuable contributions in other areas such as anti-shipping, ground attack and long-range interdiction in every major theatre of operations.

In the Mediterranean, the USAAF's 414th, 415th, 416th and 417th Night Fighter Squadrons received 100 Beaufighters in the summer of 1943, achieving their first victory in July 1943. Through the summer the squadrons conducted both daytime convoy escort and ground-attack operations, but primarily flew defensive interception missions at night. Although the Northrop P-61 Black Widow fighter began to arrive in December 1944, USAAF Beaufighters continued to fly night operations in Italy and France until late in the war.

By the autumn of 1943, the Mosquito was available in enough numbers to replace the Beaufighter as the primary night fighter of the RAF. By the end of the war some 70 pilots serving with RAF units had become aces while flying Beaufighters.

The Beaufighter is listed in the appendix to the novel KG 200 as having been flown by the German secret operations unit KG 200, which tested, evaluated and sometimes clandestinely operated captured enemy aircraft during World War II.[4]

Coastal Command

1941 saw the development of the Beaufighter Mk.IC long-range heavy fighter. This new variant entered service in May 1941 with a detachment from No. 252 Squadron operating from Malta. The aircraft proved so effective in the Mediterranean against shipping, aircraft and ground targets that Coastal Command became the major user of the Beaufighter, replacing the now obsolete Beaufort and Blenheim.

Coastal Command began to take delivery of the up-rated Mk.VIC in mid 1942. By the end of 1942 Mk VICs were being equipped with torpedo-carrying gear, enabling them to carry the British 18 in (457 mm) or the US 22.5 in (572 mm) torpedo externally. The first successful torpedo attacks by Beaufighters came in April 1943, with No. 254 Squadron sinking two merchant ships off Norway.

The Hercules Mk XVII, developing 1,735 hp (1,294 kW) at 500 ft (150 m), was installed in the Mk VIC airframe to produce the TF Mk.X (Torpedo Fighter), commonly known as the "Torbeau". The Mk X became the main production mark of the Beaufighter. The strike variant of the "Torbeau" was designated the Mk.XIC. Beaufighter TF Xs would make precision attacks on shipping at wave-top height with torpedoes or "60lb" RP-3 rockets. Early models of the Mk Xs carried metric-wavelength ASV (air-to-surface vessel) radar with "herringbone" antennae carried on the nose and outer wings, but this was replaced in late 1943 by the centimetric AI Mark VIII radar housed in a "thimble-nose" radome, enabling all-weather and night attacks.

The North Coates Strike Wing of Coastal Command, based at RAF North Coates on the Lincolnshire coast, developed tactics which combined large formations of Beaufighters using cannon and rockets to suppress flak while the Torbeaus attacked at low level with torpedoes. These tactics were put into practice in mid 1943, and in a 10-month period, 29,762 tons (27,000 tonnes) of shipping were sunk. Tactics were further adapted when shipping was moved from port during the night. North Coates Strike Wing operated as the largest anti-shipping force of the Second World War, and accounted for over 150,000 tons (136,100 tonnes) of shipping and 117 vessels for a loss of 120 Beaufighters and 241 aircrew killed or missing. This was half the total tonnage sunk by all strike wings between 1942-45.

Pacific war

.jpg)

The Beaufighter arrived at squadrons in Asia and the Pacific in mid-1942. It has often been said - although it was originally a piece of RAF whimsy quickly taken up by a British journalist - that Japanese soldiers referred to the Beaufighter as "whispering death", supposedly because attacking aircraft often were not heard (or seen) until too late.[5] The Beaufighter's Hercules engines used sleeve valves which lacked the noisy valve gear common to poppet valve engines. This was most apparent in a reduced noise level at the front of the engine.

South east Asia

In the South-East Asian Theatre, the Beaufighter Mk VIF operated from India on night missions against Japanese lines of communication in Burma and Thailand. The high-speed, low-level attacks were highly effective, despite often atrocious weather conditions, and makeshift repair and maintenance facilities.

South west Pacific

Before DAP Beaufighters arrived at Royal Australian Air Force units in the South West Pacific theatre, the Bristol Beaufighter Mk IC was employed in anti-shipping missions.

The most famous of these was the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in which they co-operated with USAAF A-20 Bostons and B-25 Mitchells. No. 30 Squadron RAAF Beaufighters flew in at mast height to provide heavy suppressive fire for the waves of attacking bombers. The Japanese convoy, under the impression that they were under torpedo attack, made the fatal tactical error of turning their ships towards the Beaufighters, leaving them exposed to skip bombing attacks by the US medium bombers. The Beaufighters inflicted maximum damage on the ships' anti-aircraft guns, bridges and crews during strafing runs with their four 20 mm nose cannons and six wing-mounted .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns. Eight transports and four destroyers were sunk for the loss of five aircraft, including one Beaufighter.

Postwar

From late 1944, RAF Beaufighter units were engaged in the Greek Civil War, finally withdrawing in 1946.

The Beaufighter was also used by the air forces of Portugal, Turkey and the Dominican Republic. It was used briefly by the Israeli Air Force.

Variants

- Beaufighter Mk IF

- Two-seat night fighter variant.

- Beaufighter Mk IC

- The "C" stood for Coastal Command variant; many were modified to carry bombs.

- Beaufighter Mk II

- However well the Beaufighter performed, the Short Stirling bomber program by late 1941 had a higher priority for the Hercules engine and the Rolls-Royce Merlin XX-powered Mk II was the result.

- Beaufighter Mk IIF

- Production night fighter variant.

- Beaufighter Mk III/IV

- The Mark III and Mark IV were to be Hercules and Merlin powered Beaufighters with a new slimmer fuselage carrying an armament of six cannon and six machine guns which would give performance improvements. The necessary costs of making the changes to the production line led to the curtailing of the Marks.[6]

- Beaufighter Mk V

- The Vs had a Boulton Paul turret with four 0.303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns mounted aft of the cockpit supplanting one pair of cannon and the wing-mounted machine guns. Only two Mk Vs were built.

- Beaufighter Mk VI

- The Hercules returned with the next major version in 1942, the Mk VI, which was eventually built to over 1,000 examples.

- Beaufighter Mk VIC

- Torpedo-carrying variant dubbed the "Torbeau".

- Beaufighter Mk VIF

- This variant was equipped with AI Mark VIII radar. Changes included a dihedral tailplane.[7]

- Beaufighter Mk VI (ITF)

- Interim torpedo fighter version.

- Beaufighter TF Mk X

- Two-seat torpedo fighter aircraft. The last major version (2,231 built) was the Mk X, among the finest torpedo and strike aircraft of its day. The later production models featured a dorsal fin.[8]

- Beaufighter Mk XIC

- Built without torpedo gear for Coastal Command use.

- Beaufighter Mk 21

- The Australian-made DAP Beaufighter. Changes included Hercules CVII engines, four 20 mm cannon in the nose, four Browning .50 in (12.7 mm) in the wings and the capacity to carry eight 5 in (130 mm) High-Velocity Aircraft Rockets (HVAR), two 250 lb (110 kg) bombs, two 500 lb (230 kg) bombs and one Mk 13 torpedo.

- Beaufighter TT Mk 10

- After the war, many RAF Beaufighters were converted into target tug aircraft.

Operators

:

Australia

Australia Canada

Canada Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic.svg.png) Germany

Germany Israel

Israel New Zealand

New Zealand Poland

Poland Portugal

Portugal South Africa

South Africa Turkey

Turkey United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States

United States

Survivors

- The National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio has completed the restoration of a rare Beaufighter Mk I. The aircraft is displayed as the USAAF Beaufighter flown by Capt. Harold Augspurger, commander of the 415th Night Fighter Squadron, who shot down an He 111 carrying German staff officers in September 1944. The Beaufighter went on display on 18 October 2006.

- The National Museum of Flight at East Fortune Airfield, east of Edinburgh, has a Beaufighter TF X (RD220). It is currently on display under restoration.

- The Royal Air Force Museum in London, UK has Beaufighter TF X, RD253, on display along with a Bristol Hercules engine. This aircraft flew with Portuguese Air Force as BF-13 in the late 1940s. It was used as an instructional airframe before its return to the UK in 1965. Restoration was completed in 1968, using components scavenged from a wide variety of sources.

- The Canada Aviation Museum presently is storing Beaufighter TF X RAF serial RD867 for future restoration. The museum aircraft is a semi-complete RAF restoration with no engines, cowlings or internal components, received in exchange for a Bristol Bolingbroke on 10 September 1969.

- A privately owned Beaufighter is currently undergoing a lengthy restoration in the UK. Its owner hopes to eventually restore it to flying condition[9].

- There are two Beaufighter Mk XXI aircraft on static display in museums in Australia, one at Moorabbin Airport, Melbourne, Australia.[10] and the other at Camden.[11]

- The Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England has a Beaufighter cockpit section on public display. Its identity is thought possibly to be T5298.

Specifications (Beaufighter TF X)

Data from Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II[12]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2: pilot, observer

- Length: 41 ft 4 in (12.6 m)

- Wingspan: 57 ft 10 in (17.65 m)

- Height: 15 ft 10 in (4.84 m)

- Wing area: 503 ft²[13] (46,73 m²)

- Empty weight: 15,592 lb (7,072 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 25,400 lb (11,521 kg)

- Powerplant: 2× Bristol Hercules 14-cylinder radial engines, 1,600 hp (1,200 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 320 mph (280 kn, 515 km/h) at 10,000 ft (3,050 m)

- Range: 1,750 mi (1,520 nmi, 2,816 km)

- Service ceiling: 19,000 ft (5,795 m) without torpedo

- Rate of climb: 1,600 ft/min (8.2 m/s) without torpedo

Armament

- 4 × 20 mm Hispano Mk III cannon (60 rpg) in nose

- Fighter Command

- 4 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns (outer starboard wing)

- 2 × .303 in (7.7 mm) machine gun (outer port wing)

- 8 × RP-3 "60 lb" (27 kg) rockets or 2× 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs

- Coastal Command

- 1 × manually-operated Vickers GO or .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning for observer

- 1 × 18 in (457 mm) torpedo

See also

Related development

- Bristol Beaufort

Comparable aircraft

- A-20 Havoc

- A-26 Invader

- de Havilland Mosquito

- P-61 Black Widow

- Heinkel He 219

- Kawasaki Ki-45

Related lists

- List of aircraft of the RAF

- List of fighter aircraft

References

- Notes

- ↑ Ashworth 1992, p. 115.

- ↑ Franks 21002, p. 171.

- ↑ Hall 1995, p. 24.

- ↑ Gilman and Clive 1978, p. 314.

- ↑ Bowyer 1994, p. 90.

- ↑ Buttler, Tony. Secret Projects: British Fighters and Bombers 1935 -1950 (British Secret Projects 3). Leicester, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-179-2.

- ↑ Franks 2002, pp. 65-67.

- ↑ Franks 2002, pp. 70-72.

- ↑ Fighter Collection Duxford - (website accessed 20/07/10)

- ↑ Australian National Aviation Museum - DAP Mark 21 Beaufighter

- ↑ "Beaufighter 156 Mk 21 A8-186." "Camden Museum of Aviation. Retrieved: 1 August 2010.

- ↑ Bridgeman 1946, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ March 1998, p. 57.

- Bibliography

- Ashworth, Chris. RAF Coastal Command: 1936-1969. London: Patrick Stephens Ltd., 1992. ISBN 1-85260-345-3.

- Bingham, Victor. Bristol Beaufighter. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, Ltd., 1994. ISBN 1-85310-122-2.

- Bowyer, Chaz. Beaufighter. London: William Kimber, 1987. ISBN 0-71830-647-3.

- Bowyer, Chaz. Beaufighter at War. London: Ian Allan Ltd., 1994. ISBN 0-71100-704-7.

- Bridgeman, Leonard, ed. "The Bristol 156 Beaufighter." Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. ISBN 1-85170-493-0.

- Flintham, V. Air Wars and Aircraft: A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present. New York: Facts on File, 1990. ISBN 0-81602-356-5.

- Franks, Richard A. The Bristol Beaufighter, a Comprehensive Guide for the Modeller. Bedford, UK: SAM Publications, 2002. ISBN 0-9533465-5-2.

- Gilman J.D. and J. Clive. KG 200. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1978. ISBN 0-85177-819-4.

- Hall, Alan W. Bristol Beaufighter (Warpaint No. 1). Dunstable, UK: Hall Park Books, 1995.

- Howard. "Bristol Beaufighter: The Inside Story". Scale Aircraft Modelling, Vol. 11, No. 10, July 1989.

- Innes, Davis J. Beaufighters over Burma - 27 Sqn RAF 1942-45. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press, 1985. ISBN 0-71371-599-5.

- March, Daniel J., ed. British Warplanes of World War II. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-874023-92-1.

- Mason, Francis K. Archive: Bristol Beaufighter. Oxford, UK: Container Publications.

- Moyes, Philip J.R. The Bristol Beaufighter I & II (Aircraft in Profile Number 137). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1966.

- Parry, Simon W. Beaufighter Squadrons in Focus. Walton on Thames, Surrey, Uk: Red Kite, 2001. ISBN 0-95380-612-X.

- Scutts, Jerry. Bristol Beaufighter (Crowood Aviation Series). Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press Ltd., 2004. ISBN 1-86126-666-9.

- Scutts, Jerry. Bristol Beaufighter in Action (Aircraft number 153). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-89747-333-7.

- Spencer, Dennis A. Looking Backwards Over Burma: Wartime Recollections of a RAF Beaufighter Navigator. Bognor Regis, West Sussex, UK: Woodfield Publishing Ltd., 2009. ISBN 1-84683-073-7.

- Thomas, Andrew. Beaufighter Aces of World War 2. Botley, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-84176-846-4.

- Wilson, Stewart. Beaufort, Beaufighter and Mosquito in Australian Service. Weston, ACT, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-95879-784-6.

External links

- Austin & Longbridge Aircraft Production

- A picture of a Merlin-engined Beaufighter II

- Bristol Beaufighter further information and pictures

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||