B cell

This article is about cell biology. For the electrical term, see: B battery.

B cells are lymphocytes that play a large role in the humoral immune response (as opposed to the cell-mediated immune response, which is governed by T cells). The principal functions of B cells are to make antibodies against antigens, perform the role of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and eventually develop into memory B cells after activation by antigen interaction. B cells are an essential component of the adaptive immune system.

The abbreviation "B", in B cell, comes from the bursa of Fabricius in birds, where they mature. In mammals, immature B cells are formed in the bone marrow, which is used as a backronym for the cells' name.[1]

Contents |

Development of B cells

Immature B cells are produced in the bone marrow of most mammals. Rabbits are an exception; their B cells develop in the appendix-sacculus rotundus. After reaching the IgM+ immature stage in the bone marrow, these immature B cells migrate to the spleen, where they are called transitional B cells, and some of these cells differentiate into mature B lymphocytes.[2]

B cell development occurs through several stages, each stage representing a change in the genome content at the antibody loci. An antibody is composed of two identical light (L) and two identical heavy (H) chains, and the genes specifying them are found in the 'V' (Variable) region and the 'C' (Constant) region. In the heavy-chain 'V' region there are three segments; V, D and J, which recombine randomly, in a process called VDJ recombination, to produce a unique variable domain in the immunoglobulin of each individual B cell. Similar rearrangements occur for light-chain 'V' region except there are only two segments involved; V and J. The list below describes the process of immunoglobulin formation at the different stages of B cell development.

| Stage | Heavy chain | Light chain | Ig | IL-7 receptor? | CD19? |

| Progenitor B cells | germline | germline | - | No | No |

| Early Pro-B cells | undergoes D-J rearrangement | germline | - | No | No |

| Late Pro-B cells | undergoes V-DJ rearrangement | germline | - | No | Yes[3] |

| Large Pre-B cells | is VDJ rearranged | germline | IgM in cytoplasm | Yes[4] | Yes |

| Small Pre-B cells | is VDJ rearranged | undergoes V-J rearrangement | IgM in cytoplasm | Yes | Yes |

| Immature B cells | is VDJ rearranged | VJ rearranged | IgM on surface | Yes | Yes |

| Mature B cells | is VDJ rearranged | VJ rearranged | IgM and IgD on surface | Yes | Yes |

When the B cell fails in any step of the maturation process, it will die by a mechanism called apoptosis, here called clonal deletion.[5] B cells are continuously produced in the bone marrow. When B cell receptors on the surface of the cell matches the detected antigens present in the body, the B cell proliferates and secretes a free form of those receptors (antibodies) with identical binding sites as the ones on the original cell surface. After activation, the cell proliferates and B memory cells would form to recognise the same antigen. This information would then be used as a part of the adaptive immune system for a more efficient and more powerful immune response for future encounters with that antigen.

B cell membrane receptors evolve and change throughout the B cell life span.[6] TACI, BCMA and BAFF-R are present on both immature B cells and mature B cells. All of these 3 receptors may be inhibited by Belimumab. CD20 is expressed on all stages of B cell development except the first and last; it is present from pre-pre B cells through memory cells, but not on either pro-B cells or plasma cells.[7]

Immune Tolerance

Like its fellow lymphocyte, the T cell, immature B cells are tested for auto-reactivity by the immune system before leaving the bone marrow. In the bone marrow (the central lymphoid organ), central tolerance is produced. The immature B cells whose B cell Receptors (BCRs) bind too strongly to self antigens will not be allowed to mature. If B cells are found to be highly reactive to self, three mechanisms can occur.

- Clonal deletion: the removal, usually by apoptosis, of B cells of a particular self antigen specificity.

- Receptor editing: the BCRs of self reactive B cells are given an opportunity to rearrange their conformation. This process occurs via the continued expression of the Recombination activating gene (RAG) gene. Through the help of RAG, receptor editing involves light chain gene rearrangement of the B cell receptor. If receptor editing fails to produce a BCR that is less autoreactive, apoptosis will occur. Note that defects in the RAG-1 and RAG-2 genes are implicated in Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID). The inability to recombine and generate new receptors lead to failure of maturity for both B cells and T cells.

- Anergy: B cells enters a state of permanent unresponsiveness when it binds with weakly cross-linking self antigens that are small and soluble.

Functions

The human body makes millions of different types of B cells each day that circulate in the blood and lymphatic system performing the role of immune surveillance. They do not produce antibodies until they become fully activated. Each B cell has a unique receptor protein (referred to as the B cell receptor (BCR)) on its surface that will bind to one particular antigen. The BCR is a membrane-bound immunoglobulin, and it is this molecule that allows the distinction of B cells from other types of lymphocyte, as well as being the main protein involved in B cell activation. Once a B cell encounters its cognate antigen and receives an additional signal from a T helper cell, it can further differentiate into one of the two types of B cells listed below (plasma B cells and memory B cells). The B cell may either become one of these cell types directly or it may undergo an intermediate differentiation step, the germinal center reaction, where the B cell will hypermutate the variable region of its immunoglobulin gene ("somatic hypermutation") and possibly undergo class switching.

Clonality

B cells exist as clones. All B cells derive from a particular cell, and thus, the antibodies their differentiated progenies (see below) produce can recognize and/or bind the same components (epitope) of a given antigen. Such clonality has important consequences, as immunogenic memory relies on it. The great diversity in immune response comes about because there are up to 109 clones with specificities for recognizing different antigens. A single B cell or a clone of cells with shared specificity upon encountering its specific antigen divides to produce many B cells. Most of such B cells differentiate into plasma cells that secrete antibodies into blood that bind the same epitope that elicited proliferation in the first place. A small minority survives as memory cells that can recognize only the same epitope. However, with each cycle, the number of surviving memory cells increases. The increase is accompanied by affinity maturation which induces the survival of B cells that bind to the particular antigen with high affinity. This subsequent amplification with improved specificity of immune response is known as secondary immune response. B cells that encounter antigen for the first time are known as naive B cells.

B cell types

- Plasma B cells (also known as plasma cells) are large B cells that have been exposed to antigen and produce and secrete large amounts of antibodies, which assist in the destruction of microbes by binding to them and making them easier targets for phagocytes and activation of the complement system. They are sometimes referred to as antibody factories. An electron micrograph of these cells reveals large amounts of rough endoplasmic reticulum, responsible for synthesizing the antibody, in the cell's cytoplasm. These are short lived cells and undergo apoptosis when the inciting agent that induced immune response is eliminated. This occurs because of cessation of continuous exposure to various colony stimulating factors required for survival.

- Memory B cells are formed from activated B cells that are specific to the antigen encountered during the primary immune response. These cells are able to live for a long time, and can respond quickly following a second exposure to the same antigen.

- B-1 cells express IgM in greater quantities than IgG and their receptors show polyspecificity, meaning that they have low affinities for many different antigens, but have a preference for other immunoglobulins, self antigens and common bacterial polysaccharides. B-1 cells are present in low numbers in the lymph nodes and spleen and are instead found predominantly in the peritoneal and pleural cavities.[8][9]

- B-2 cells are the conventional B cells most texts refer to.

- Marginal-zone B cells

- Follicular B Cells

Recognition of antigen by B cells

A critical difference between B cells and T cells is how each lymphocyte recognizes its antigen. B cells recognize their cognate antigen in its native form. They recognize free (soluble) antigen in the blood or lymph using their BCR or membrane bound-immunoglobulin. In contrast, T cells recognize their cognate antigen in a processed form, as a peptide fragment presented by an antigen presenting cell's MHC molecule to the T cell receptor.

Activation of B cells

B cell recognition of antigen is not the only element necessary for B cell activation (a combination of clonal proliferation and terminal differentiation into plasma cells). B cells that have not been exposed to antigen, also known as naïve B cells, can be activated in a T cell-dependent or -independent manner.

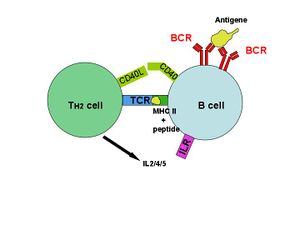

T cell-dependent activation

Once a pathogen is ingested by an antigen-presenting cell such as a macrophage or dendritic cell, the pathogen's proteins are then digested to peptides and attached to a class II MHC protein. This complex is then moved to the outside of the cell membrane. The macrophage is now activated to deliver multiple signals to a specific T cell that recognizes the peptide presented. The T cell is then stimulated to produce autocrines (Refer to Autocrine signalling), resulting in the proliferation and differentiation to effector and memory T cells. Helper T cells (i.e. CD4+ T cells) then activate specific B cells through a phenomenon known as an Immunological synapse. Activated B cells subsequently produce antibodies which assist in inhibiting pathogens until phagocytes (i.e. macrophages, neutrophils) or the complement system for example clears the host of the pathogen(s).

Most antigens are T-dependent, meaning T cell help is required for maximal antibody production. With a T-dependent antigen, the first signal comes from antigen cross linking the B cell receptor (BCR) and the second signal comes from co-stimulation provided by a T cell. T dependent antigens contain proteins that are presented on B cell Class II MHC to a special subtype of T cell called a Th2 cell. When a B cell processes and presents the same antigen to the primed Th cell, the T cell secretes cytokines that activate the B cell. These cytokines trigger B cell proliferation and differentiation into plasma cells. Isotype switching to IgG, IgA, and IgE and memory cell generation occur in response to T-dependent antigens. This isotype switching is known as Class Switch Recombination (CSR). Once this switch has occurred, that particular B cell will usually no longer make the earlier isotypes, IgM or IgD.

T cell-independent activation

Many antigens are T cell-independent in that they can deliver both of the signals to the B cell. Mice without a thymus (nude or athymic mice that do not produce any T cells) can respond to T independent antigens. Many bacteria have repeating carbohydrate epitopes that stimulate B cells, by cross-linking the IgM antigen receptors in the B cell, responding with IgM synthesis in the absence of T cell help. There are two types of T cell independent activation; Type 1 T cell-independent (polyclonal) activation, and type 2 T cell-independent activation (in which macrophages present several of the same antigen in a way that causes cross-linking of antibodies on the surface of B cells).

The ancestral roots of B cells

In an October 2006 issue of Nature Immunology, certain B cells of basal vertebrates (like fish and amphibians) were shown to be capable of phagocytosis, a function usually associated with cells of the innate immune system. The authors postulate that these phagocytic B cells represent the ancestral history shared between macrophages and lymphocytes. B cells may have evolved from macrophage-like cells during the formation of the adaptive immune system[10].

B cells in humans (and other vertebrates) are nevertheless able to endocytose antibody-fixed pathogens, and it is through this route that MHC Class II presentation by B cells is possible, allowing Th2 help and stimulation of B cell proliferation. This is purely for the benefit of MHC Class II presentation, not as a significant method of reducing the pathogen load.

Origin of the term

The abbreviation "B" in B cell originally came from Bursa of Fabricius, an organ in birds in which avian B cells mature.[11] When it was discovered that in most mammals immature B cells are formed in bone marrow, the word B cell continued to be used, although other blood cells also originate from pluripotent stem cells in the bone marrow. The fact that bone and bursa both start with the letter 'B' is a coincidence.

Aberrant antibody production by B cells is implicated in many autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Additional image

See also

- Affinity maturation

- Antibody

- Clonal selection

- Original antigenic sin

References

- ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts k, Walter P (2002) Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science: New York, NY pg 1367.

- ↑ Allman D, Srivastava B, Lindsley RC (February 2004). "Alternative routes to maturity: branch points and pathways for generating follicular and marginal zone B cells". Immunol. Rev. 197: 147–60. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0108.x. PMID 14962193. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0105-2896&date=2004&volume=197&spage=147.

- ↑ "B Cell Development". http://www.microvet.arizona.edu/Courses/MIC419/Tutorials/Bcelldevelopment.html#generation. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ↑ "Immunology, Biology 328". http://bioweb.wku.edu/courses/biol328/Lecture11.html. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ↑ Parham, P. (2005). The Immune System, Garland Science Publishing, New York, NY.

- ↑ "Hyperactive_Blymphocytes_lifespan_receptors". http://www.healthvalue.net/Hyperactive_Blymphocytes_lifespan_receptors.html. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Bona, Constantin; Francisco A. Bonilla (1996). "5". Textbook of Immunology. Martin Soohoo (2 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 102. ISBN 9783718605965.

- ↑ Montecino-Rodriguez, Encarnacion; Kenneth Dorshkind (2006-09). "New perspectives in B-1 B cell development and function". Trends in Immunology (Elsevier B.V.) 27 (9): 428–433. doi:10.1016/j.it.2006.07.005. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6W7H-4KGG1T1-2&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=923c447f162114b76b1a9ca6f3e02a06. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ↑ Tung, James; Leonore A Herzenberg (2007-04). ""Unraveling B-1 progenitors"". Current Opinion in Immunology (Elsevier B.V.) 19 (2): 150–155. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.012. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VS1-4N2D5Y5-6&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=f47493140685f1e9e8835d3cf7c1b2f5. Retrieved 2008-05.

- ↑ J. Li, D.R. Barreda, Y.-A. Zhang, H. Boshra, A.E. Gelman, S. LaPatra, L. Tort & J.O. Sunyer (2006). "B lymphocytes from early vertebrates have potent phagocytic and microbicidal abilities". Nature Immunology 7: 1116–1124. doi:10.1038/ni1389. PMID 16980980.

- ↑ Bursa of Fabricius

- ↑ Goldsby, Richard; Kindt, TJ; Osborne, BA; Janis Kuby (2003). Immunology Fifth Edition. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-07167-4947-5.

External links

- MeSH B-Lymphocytes

- B Cells and T Cells

- B Cell Development and Generation of Lymphocyte Diversity

- Interactive Animation of B Cell Maturation (requires Flash video software)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||