Autobiography

An autobiography (from the Greek, αὐτός-autos self + βίος-bios life + γράφειν-graphein to write) is a book about the life of a person, written by that person.

Contents |

Origin of the term

The word autobiography was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English periodical, the Monthly Review, when he suggested the word as a hybrid but condemned it as 'pedantic'; but its next recorded use was in its present sense by Robert Southey in 1809.[1] The form of autobiography however goes back to antiquity. Biographers generally rely on a wide variety of documents and viewpoints; an autobiography however may be based entirely on the writer's memory. Closely associated with autobiography (and sometimes difficult to precisely distinguish from it) is the form of memoir.

See also: List of autobiographies and Category:Autobiographies for examples.

Autobiography through the ages

The classical period: Apologia, oration, confession

In antiquity such works were typically entitled apologia, implying as an example of much self-justification as self-documentation. John Henry Newman's autobiography (first published in 1864) is entitled Apologia Pro Vita Sua in reference to this tradition.

The pagan rhetor Libanius (c. 314–394) framed his life memoir (Oration I begun in 374) as one of his orations, not of a public kind, but of a literary kind that could be read aloud in privacy.

Augustine (354–430) applied the title Confessions to his autobiographical work, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau used the same title in the 18th century, initiating the chain of confessional and sometimes racy and highly self-critical, autobiographies of the Romantic era and beyond.

In the spirit of Augustine's Confessions is the 11th-century Historia Calamitatum of Peter Abelard, outstanding as an autobiographical document of its period.

Early autobiographies

In the 15th century, a spanish noble woman named Leonor López de Córdoba wrote her Memorias, which are considered to be the first autobiography in Castillian.

Zāhir ud-Dīn Mohammad Bābur,who founded the Mughal dynasty of South Asia kept a journal Bāburnāma (Chagatai/Persian: بابر نامہ; literally: "Book of Babur" or "Letters of Babur") which was written between 1493 and 1529.

One of the first great autobiographies of the Renaissance is that of the sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571), written between 1556 and 1558, and entitled by him simply Vita (Italian: Life). He declares at the start: "No matter what sort he is, everyone who has to his credit what are or really seem great achievements, if he cares for truth and goodness, ought to write the story of his own life in his own hand; but no one should venture on such a splendid undertaking before he is over forty."[2] These criteria for autobiography generally persisted until recent times, and most serious autobiographies of the next three hundred years conformed to them.

Another autobiography of the period is De vita propria, by the Italian physician and astrologer Gerolamo Cardano (1574).

The earliest known autobiography in English is the early 15th-century Booke of Margery Kempe, describing among other things her pilgrimage to the Holy Land and visit to Rome. The book remained in manuscript and was not published until 1936.

Notable English autobiographies of the seventeenth century include those of Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1643, published 1764) and John Bunyan (Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, 1666).

Memoirs

A memoir is slightly different in character from an autobiography. While an autobiography typically focuses on the "life and times" of the writer, a memoir has a narrower, more intimate focus on his or her own memories, feelings and emotions. Memoirs have often been written by politicians or military leaders as a way to record and publish an account of their public exploits. One early example is that of Leonor López de Córdoba (1362–1420) who wrote what is supposed to be the first autobiography in Spanish. The English Civil War (1642–1651) provoked a number of examples of this genre, including works by Sir Edmund Ludlow and Sir John Reresby. French examples from the same period include the memoirs of Cardinal de Retz (1614–1679) and the Duc de Saint-Simon (1675–1756).

18th and 19th centuries

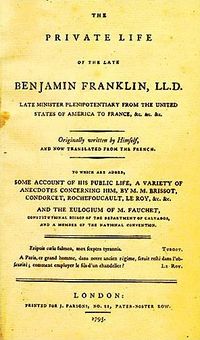

Notable 18th-century autobiographies in English include those of Edward Gibbon and Benjamin Franklin. Following the trend of Romanticism, which greatly emphasised the role and the nature of the individual, and in the footsteps of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Confessions, a more intimate form of autobiography, exploring the subject's emotions, came into fashion. An English example is William Hazlitt's Liber Amoris (1823), a painful examination of the writer's love-life.

With the rise of education, cheap newspapers and cheap printing, modern concepts of fame and celebrity began to develop, and the beneficiaries of this were not slow to cash in on this by producing autobiographies. It became the expectation—rather than the exception—that those in the public eye should write about themselves—not only writers such as Charles Dickens (who also incorporated autobiographical elements in his novels) and Anthony Trollope, but also politicians (e.g. Henry Brooks Adams), philosophers (e.g. John Stuart Mill), churchmen such as Cardinal Newman, and entertainers such as P. T. Barnum. Increasingly, in accordance with romantic taste, these accounts also began to deal, amongst other topics, with aspects of childhood and upbringing—far removed from the principles of "Cellinian" autobiography.

Nature of autobiography

Autobiographical works are by nature subjective. The inability—or unwillingness—of the author to accurately recall memories has in certain cases resulted in misleading or incorrect information. Some sociologists and psychologists have noted that autobiography offers the author the ability to recreate history.[3]

Versions of the autobiography form

Autobiographies as critiques of totalitarianism

Victims and opponents of totalitarian regimes have been able to present striking critiques of these regimes through autobiographical accounts of their oppression. Among the more renowned of such works are the writings of Primo Levi, one of many personal accounts of the Shoah. Similarly, there are many works detailing atrocities and malevolence of Communist regimes (e.g., Nadezhda Mandelstam's Hope against Hope).

Sensationalist and celebrity "autobiographies"

From the 17th century onwards, "scandalous memoirs" by supposed libertines, serving a public taste for titillation, have been frequently published. Typically pseudonymous, they were (and are) largely works of fiction written by ghostwriters.

So-called "autobiographies" of modern professional athletes and media celebrities—and to a lesser extent about politicians, generally written by a ghostwriter, are routinely published. Some celebrities, such as Naomi Campbell, admit to not having read their "autobiographies".

Autobiographies of the non-famous

Until recent years, few people without some genuine claim to fame wrote or published autobiographies for the general public. With the critical and commercial success in the United States of such memoirs as Angela’s Ashes and The Color of Water, however, more and more people have been encouraged to try their hand at this genre.

Fake autobiographies

This trend has also encouraged fake autobiographies, particularly those associated with 'misery lit,' where the writer has allegedly suffered from being a part of a dysfunctional family, or from social problems, or political repression.

Fictional autobiography

The term "fictional autobiography" has been coined to define novels about a fictional character written as though the character were writing their own biography, of which Daniel Defoe's Moll Flanders, is an early example. Charles Dickens' David Copperfield is another such classic, and J. D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye is a well-known modern example of fictional autobiography. Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre is yet another example of fictional autobiography, as noted on the front page of the original version. The term may also apply to works of fiction purporting to be autobiographies of real characters, e.g., Robert Nye's Memoirs of Lord Byron.

See also

References

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, Autobiography

- ↑ Benvenuto Cellini, tr. George Bull, The Autobiography, London 1966 p. 15.

- ↑ Berghegger, Scott. (2005). "Sublime Inauthenticity: How critical is truth in autobiography?" Student Pulse. http://studentpulse.com/articles/31/sublime-inauthenticity-how-critical-is-truth-in-autobiography

Further reading

- Barros, Carolyn A. (1998). Autobiography: Narrative of Transformation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Buckley, Jerome Hamilton (1994). The Turning Key: Autobiography and the Subjective Impulse Since 1800. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Lejeune, Philippe (1988). On Autobiography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Olney, James (1998). Memory & Narrative: The Weave of Life-Writing. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Pascal, Roy (1960). Design and Truth in Autobiography. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Reynolds, Dwight F., ed (2001). Interpreting the Self: Autobiography in the Arabic Literary Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Wu, Pey-Yi (1990). The Confucian's Progress: Autobiographical Writings in Traditional China. Princeton: Princeton University Press.