Autism

| Autism | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Repetitively stacking or lining up objects is a behavior occasionally associated with individuals with autism. |

|

| ICD-10 | F84.0 |

| ICD-9 | 299.00 |

| OMIM | 209850 |

| DiseasesDB | 1142 |

| MedlinePlus | 001526 |

| eMedicine | med/3202 ped/180 |

| MeSH | D001321 |

| GeneReviews | Autism overview |

Autism is a disorder of neural development characterized by impaired social interaction and communication, and by restricted and repetitive behavior. These signs all begin before a child is three years old.[1] Autism affects information processing in the brain by altering how nerve cells and their synapses connect and organize; how this occurs is not well understood.[2] It is one of three recognized disorders in the autism spectrum (ASDs), the other two being Asperger syndrome, which lacks delays in cognitive development and language, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (commonly abbreviated as PDD-NOS), which is diagnosed when the full set of criteria for autism or Asperger syndrome are not met.[3]

Autism has a strong genetic basis, although the genetics of autism are complex and it is unclear whether ASD is explained more by rare mutations, or by rare combinations of common genetic variants.[4] In rare cases, autism is strongly associated with agents that cause birth defects.[5] Controversies surround other proposed environmental causes, such as heavy metals, pesticides or childhood vaccines;[6] the vaccine hypotheses are biologically implausible and lack convincing scientific evidence.[7] The prevalence of autism is about 1–2 per 1,000 people; the prevalence of ASD is about 6 per 1,000, with about four times as many males as females. The number of people diagnosed with autism has increased dramatically since the 1980s, partly due to changes in diagnostic practice; the question of whether actual prevalence has increased is unresolved.[8]

Parents usually notice signs in the first two years of their child's life.[9] The signs usually develop gradually, but some autistic children first develop more normally and then regress.[10] Although early behavioral or cognitive intervention can help autistic children gain self-care, social, and communication skills, there is no known cure.[9] Not many children with autism live independently after reaching adulthood, though some become successful.[11] An autistic culture has developed, with some individuals seeking a cure and others believing autism should be accepted as a difference and not treated as a disorder.[12]

Contents |

Characteristics

Autism is a highly variable neurodevelopmental disorder[13] that first appears during infancy or childhood, and generally follows a steady course without remission.[14] Overt symptoms gradually begin after the age of six months, become established by age two or three years,[15] and tend to continue through adulthood, although often in more muted form.[16] It is distinguished not by a single symptom, but by a characteristic triad of symptoms: impairments in social interaction; impairments in communication; and restricted interests and repetitive behavior. Other aspects, such as atypical eating, are also common but are not essential for diagnosis.[17] Autism's individual symptoms occur in the general population and appear not to associate highly, without a sharp line separating pathologically severe from common traits.[18]

Social development

Social deficits distinguish autism and the related autism spectrum disorders (ASD; see Classification) from other developmental disorders.[16] People with autism have social impairments and often lack the intuition about others that many people take for granted. Noted autistic Temple Grandin described her inability to understand the social communication of neurotypicals, or people with normal neural development, as leaving her feeling "like an anthropologist on Mars".[19]

Unusual social development becomes apparent early in childhood. Autistic infants show less attention to social stimuli, smile and look at others less often, and respond less to their own name. Autistic toddlers differ more strikingly from social norms; for example, they have less eye contact and turn taking, and are more likely to communicate by manipulating another person's hand.[20] Three- to five-year-old autistic children are less likely to exhibit social understanding, approach others spontaneously, imitate and respond to emotions, communicate nonverbally, and take turns with others. However, they do form attachments to their primary caregivers.[21] Most autistic children display moderately less attachment security than non-autistic children, although this difference disappears in children with higher mental development or less severe ASD.[22] Older children and adults with ASD perform worse on tests of face and emotion recognition.[23]

Children with high-functioning autism suffer from more intense and frequent loneliness compared to non-autistic peers, despite the common belief that children with autism prefer to be alone. Making and maintaining friendships often proves to be difficult for those with autism. For them, the quality of friendships, not the number of friends, predicts how lonely they feel. Functional friendships, such as those resulting in invitations to parties, may affect the quality of life more deeply.[24]

There are many anecdotal reports, but few systematic studies, of aggression and violence in individuals with ASD. The limited data suggest that, in children with mental retardation, autism is associated with aggression, destruction of property, and tantrums. A 2007 study interviewed parents of 67 children with ASD and reported that about two-thirds of the children had periods of severe tantrums and about one-third had a history of aggression, with tantrums significantly more common than in non-autistic children with language impairments.[25] A 2008 Swedish study found that, of individuals aged 15 or older discharged from hospital with a diagnosis of ASD, those who committed violent crimes were significantly more likely to have other psychopathological conditions such as psychosis.[26]

Communication

About a third to a half of individuals with autism do not develop enough natural speech to meet their daily communication needs.[27] Differences in communication may be present from the first year of life, and may include delayed onset of babbling, unusual gestures, diminished responsiveness, and vocal patterns that are not synchronized with the caregiver. In the second and third years, autistic children have less frequent and less diverse babbling, consonants, words, and word combinations; their gestures are less often integrated with words. Autistic children are less likely to make requests or share experiences, and are more likely to simply repeat others' words (echolalia)[28][29] or reverse pronouns.[30] Joint attention seems to be necessary for functional speech, and deficits in joint attention seem to distinguish infants with ASD:[3] for example, they may look at a pointing hand instead of the pointed-at object,[20][29] and they consistently fail to point at objects in order to comment on or share an experience.[3] Autistic children may have difficulty with imaginative play and with developing symbols into language.[28][29]

In a pair of studies, high-functioning autistic children aged 8–15 performed equally well as, and adults better than, individually matched controls at basic language tasks involving vocabulary and spelling. Both autistic groups performed worse than controls at complex language tasks such as figurative language, comprehension and inference. As people are often sized up initially from their basic language skills, these studies suggest that people speaking to autistic individuals are more likely to overestimate what their audience comprehends.[31]

Repetitive behavior

Autistic individuals display many forms of repetitive or restricted behavior, which the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R)[32] categorizes as follows.

- Stereotypy is repetitive movement, such as hand flapping, making sounds, head rolling, or body rocking.

- Compulsive behavior is intended and appears to follow rules, such as arranging objects in stacks or lines.

- Sameness is resistance to change; for example, insisting that the furniture not be moved or refusing to be interrupted.

- Ritualistic behavior involves an unvarying pattern of daily activities, such as an unchanging menu or a dressing ritual. This is closely associated with sameness and an independent validation has suggested combining the two factors.[32]

- Restricted behavior is limited in focus, interest, or activity, such as preoccupation with a single television program, toy, or game.

- Self-injury includes movements that injure or can injure the person, such as eye poking, skin picking, hand biting, and head banging.[3] A 2007 study reported that self-injury at some point affected about 30% of children with ASD.[25]

No single repetitive or self-injurious behavior seems to be specific to autism, but only autism appears to have an elevated pattern of occurrence and severity of these behaviors.[33]

Other symptoms

Autistic individuals may have symptoms that are independent of the diagnosis, but that can affect the individual or the family.[17] An estimated 0.5% to 10% of individuals with ASD show unusual abilities, ranging from splinter skills such as the memorization of trivia to the extraordinarily rare talents of prodigious autistic savants.[34] Many individuals with ASD show superior skills in perception and attention, relative to the general population.[35] Sensory abnormalities are found in over 90% of those with autism, and are considered core features by some,[36] although there is no good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate autism from other developmental disorders.[37] Differences are greater for under-responsivity (for example, walking into things) than for over-responsivity (for example, distress from loud noises) or for sensation seeking (for example, rhythmic movements).[38] An estimated 60%–80% of autistic people have motor signs that include poor muscle tone, poor motor planning, and toe walking;[36] deficits in motor coordination are pervasive across ASD and are greater in autism proper.[39]

Unusual eating behavior occurs in about three-quarters of children with ASD, to the extent that it was formerly a diagnostic indicator. Selectivity is the most common problem, although eating rituals and food refusal also occur;[25] this does not appear to result in malnutrition. Although some children with autism also have gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, there is a lack of published rigorous data to support the theory that autistic children have more or different GI symptoms than usual;[40] studies report conflicting results, and the relationship between GI problems and ASD is unclear.[41]

Parents of children with ASD have higher levels of stress.[42] Siblings of children with ASD report greater admiration of and less conflict with the affected sibling than siblings of unaffected children or those with Down syndrome; siblings of individuals with ASD have greater risk of negative well-being and poorer sibling relationships as adults.[43]

Classification

Autism is one of the five pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), which are characterized by widespread abnormalities of social interactions and communication, and severely restricted interests and highly repetitive behavior.[14] These symptoms do not imply sickness, fragility, or emotional disturbance.[16]

Of the five PDD forms, Asperger syndrome is closest to autism in signs and likely causes; Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder share several signs with autism, but may have unrelated causes; PDD not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS; also called atypical autism) is diagnosed when the criteria are not met for a more specific disorder.[44] Unlike with autism, people with Asperger syndrome have no substantial delay in language development.[1] The terminology of autism can be bewildering, with autism, Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS often called the autism spectrum disorders (ASD)[9] or sometimes the autistic disorders,[45] whereas autism itself is often called autistic disorder, childhood autism, or infantile autism. In this article, autism refers to the classic autistic disorder; in clinical practice, though, autism, ASD, and PDD are often used interchangeably.[46] ASD, in turn, is a subset of the broader autism phenotype, which describes individuals who may not have ASD but do have autistic-like traits, such as avoiding eye contact.[47]

The manifestations of autism cover a wide spectrum, ranging from individuals with severe impairments—who may be silent, mentally disabled, and locked into hand flapping and rocking—to high functioning individuals who may have active but distinctly odd social approaches, narrowly focused interests, and verbose, pedantic communication.[48] Because the behavior spectrum is continuous, boundaries between diagnostic categories are necessarily somewhat arbitrary.[36] Sometimes the syndrome is divided into low-, medium- or high-functioning autism (LFA, MFA, and HFA), based on IQ thresholds,[49] or on how much support the individual requires in daily life; these subdivisions are not standardized and are controversial. Autism can also be divided into syndromal and non-syndromal autism; the syndromal autism is associated with severe or profound mental retardation or a congenital syndrome with physical symptoms, such as tuberous sclerosis.[50] Although individuals with Asperger syndrome tend to perform better cognitively than those with autism, the extent of the overlap between Asperger syndrome, HFA, and non-syndromal autism is unclear.[51]

Some studies have reported diagnoses of autism in children due to a loss of language or social skills, as opposed to a failure to make progress, typically from 15 to 30 months of age. The validity of this distinction remains controversial; it is possible that regressive autism is a specific subtype,[10][20][28][52] or that there is a continuum of behaviors between autism with and without regression.[53]

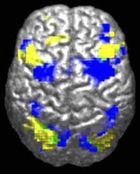

Research into causes has been hampered by the inability to identify biologically meaningful subpopulations[54] and by the traditional boundaries between the disciplines of psychiatry, psychology, neurology and pediatrics.[55] Newer technologies such as fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging can help identify biologically relevant phenotypes (observable traits) that can be viewed on brain scans, to help further neurogenetic studies of autism;[56] one example is lowered activity in the fusiform face area of the brain, which is associated with impaired perception of people versus objects.[2] It has been proposed to classify autism using genetics as well as behavior.[57]

Causes

It has long been presumed that there is a common cause at the genetic, cognitive, and neural levels for autism's characteristic triad of symptoms.[58] However, there is increasing suspicion that autism is instead a complex disorder whose core aspects have distinct causes that often co-occur.[58][59]

Autism has a strong genetic basis, although the genetics of autism are complex and it is unclear whether ASD is explained more by rare mutations with major effects, or by rare multigene interactions of common genetic variants.[4][61] Complexity arises due to interactions among multiple genes, the environment, and epigenetic factors which do not change DNA but are heritable and influence gene expression.[16] Studies of twins suggest that heritability is 0.7 for autism and as high as 0.9 for ASD, and siblings of those with autism are about 25 times more likely to be autistic than the general population.[36] However, most of the mutations that increase autism risk have not been identified. Typically, autism cannot be traced to a Mendelian (single-gene) mutation or to a single chromosome abnormality like fragile X syndrome, and none of the genetic syndromes associated with ASDs has been shown to selectively cause ASD.[4] Numerous candidate genes have been located, with only small effects attributable to any particular gene.[4] The large number of autistic individuals with unaffected family members may result from copy number variations—spontaneous deletions or duplications in genetic material during meiosis.[62] Hence, a substantial fraction of autism cases may be traceable to genetic causes that are highly heritable but not inherited: that is, the mutation that causes the autism is not present in the parental genome.[60]

Several lines of evidence point to synaptic dysfunction as a cause of autism.[2] Some rare mutations may lead to autism by disrupting some synaptic pathways, such as those involved with cell adhesion.[63] Gene replacement studies in mice suggest that autistic symptoms are closely related to later developmental steps that depend on activity in synapses and on activity-dependent changes.[64] All known teratogens (agents that cause birth defects) related to the risk of autism appear to act during the first eight weeks from conception, and though this does not exclude the possibility that autism can be initiated or affected later, it is strong evidence that autism arises very early in development.[5] Although evidence for other environmental causes is anecdotal and has not been confirmed by reliable studies,[6] extensive searches are underway.[65] Environmental factors that have been claimed to contribute to or exacerbate autism, or may be important in future research, include certain foods, infectious disease, heavy metals, solvents, diesel exhaust, PCBs, phthalates and phenols used in plastic products, pesticides, brominated flame retardants, alcohol, smoking, illicit drugs, vaccines[8], and prenatal stress[66], although no links have been found, and some have been completely dis-proven. Parents may first become aware of autistic symptoms in their child around the time of a routine vaccination, and this has given rise to theories that vaccines or their preservatives cause autism, which was fueled by a scientific study which has since been proven to have been falsified. Although these theories lack convincing scientific evidence and are biologically implausible, parental concern about autism has led to lower rates of childhood immunizations and higher likelihood of measles outbreaks in some areas.[7]

Mechanism

Autism's symptoms result from maturation-related changes in various systems of the brain. How autism occurs is not well understood. Its mechanism can be divided into two areas: the pathophysiology of brain structures and processes associated with autism, and the neuropsychological linkages between brain structures and behaviors.[67] The behaviors appear to have multiple pathophysiologies.[18]

Pathophysiology

Unlike many other brain disorders such as Parkinson's, autism does not have a clear unifying mechanism at either the molecular, cellular, or systems level; it is not known whether autism is a few disorders caused by mutations converging on a few common molecular pathways, or is (like intellectual disability) a large set of disorders with diverse mechanisms.[13] Autism appears to result from developmental factors that affect many or all functional brain systems,[69] and to disturb the timing of brain development more than the final product.[68] Neuroanatomical studies and the associations with teratogens strongly suggest that autism's mechanism includes alteration of brain development soon after conception.[5] This anomaly appears to start a cascade of pathological events in the brain that are significantly influenced by environmental factors.[70] Just after birth, the brains of autistic children tend to grow faster than usual, followed by normal or relatively slower growth in childhood. It is not known whether early overgrowth occurs in all autistic children. It seems to be most prominent in brain areas underlying the development of higher cognitive specialization.[36] Hypotheses for the cellular and molecular bases of pathological early overgrowth include the following:

- An excess of neurons that causes local overconnectivity in key brain regions.[71]

- Disturbed neuronal migration during early gestation.[72][73]

- Unbalanced excitatory–inhibitory networks.[73]

- Abnormal formation of synapses and dendritic spines,[73] for example, by modulation of the neurexin–neuroligin cell-adhesion system,[74] or by poorly regulated synthesis of synaptic protein.[75] Disrupted synaptic development may also contribute to epilepsy, which may explain why the two conditions are associated.[76]

Interactions between the immune system and the nervous system begin early during the embryonic stage of life, and successful neurodevelopment depends on a balanced immune response. It is possible that aberrant immune activity during critical periods of neurodevelopment is part of the mechanism of some forms of ASD.[77] Although some abnormalities in the immune system have been found in specific subgroups of autistic individuals, it is not known whether these abnormalities are relevant to or secondary to autism's disease processes.[78] As autoantibodies are found in conditions other than ASD, and are not always present in ASD,[79] the relationship between immune disturbances and autism remains unclear and controversial.[72]

The relationship of neurochemicals to autism is not well understood; several have been investigated, with the most evidence for the role of serotonin and of genetic differences in its transport.[2] Some data suggest an increase in several growth hormones; other data argue for diminished growth factors.[80] Also, some inborn errors of metabolism are associated with autism but probably account for less than 5% of cases.[81]

The mirror neuron system (MNS) theory of autism hypothesizes that distortion in the development of the MNS interferes with imitation and leads to autism's core features of social impairment and communication difficulties. The MNS operates when an animal performs an action or observes another animal perform the same action. The MNS may contribute to an individual's understanding of other people by enabling the modeling of their behavior via embodied simulation of their actions, intentions, and emotions.[82] Several studies have tested this hypothesis by demonstrating structural abnormalities in MNS regions of individuals with ASD, delay in the activation in the core circuit for imitation in individuals with Asperger syndrome, and a correlation between reduced MNS activity and severity of the syndrome in children with ASD.[83] However, individuals with autism also have abnormal brain activation in many circuits outside the MNS[84] and the MNS theory does not explain the normal performance of autistic children on imitation tasks that involve a goal or object.[85]

ASD-related patterns of low function and aberrant activation in the brain differ depending on whether the brain is doing social or nonsocial tasks.[87] In autism there is evidence for reduced functional connectivity of the default network, a large-scale brain network involved in social and emotional processing, with intact connectivity of the task-positive network, used in sustained attention and goal-directed thinking. In people with autism the two networks are not negatively correlated in time, suggesting an imbalance in toggling between the two networks, possibly reflecting a disturbance of self-referential thought.[88] A 2008 brain-imaging study found a specific pattern of signals in the cingulate cortex which differs in individuals with ASD.[89]

The underconnectivity theory of autism hypothesizes that autism is marked by underfunctioning high-level neural connections and synchronization, along with an excess of low-level processes.[90] Evidence for this theory has been found in functional neuroimaging studies on autistic individuals[31] and by a brainwave study that suggested that adults with ASD have local overconnectivity in the cortex and weak functional connections between the frontal lobe and the rest of the cortex.[91] Other evidence suggests the underconnectivity is mainly within each hemisphere of the cortex and that autism is a disorder of the association cortex.[92]

From studies based on event-related potentials, transient changes to the brain's electrical activity in response to stimuli, there is considerable evidence for differences in autistic individuals with respect to attention, orientiation to auditory and visual stimuli, novelty detection, language and face processing, and information storage; several studies have found a preference for non-social stimuli.[93] For example, magnetoencephalography studies have found evidence in autistic children of delayed responses in the brain's processing of auditory signals.[94]

In the genetic area, relations have been found between autism and schizophrenia based on duplications and deletions of chromosomes; research showed that schizophrenia and autism are significantly more common in combination with 1q21.1 deletion syndrome. Research on autism/schizophrenia relations for chromosome 15 (15q13.3), chromosome 16 (16p13.1) and chromosome 17 (17p12) are inconclusive.[95]

Neuropsychology

Two major categories of cognitive theories have been proposed about the links between autistic brains and behavior.

The first category focuses on deficits in social cognition. The empathizing–systemizing theory postulates that autistic individuals can systemize—that is, they can develop internal rules of operation to handle events inside the brain—but are less effective at empathizing by handling events generated by other agents. An extension, the extreme male brain theory, hypothesizes that autism is an extreme case of the male brain, defined psychometrically as individuals in whom systemizing is better than empathizing;[96] this extension is controversial, as many studies contradict the idea that baby boys and girls respond differently to people and objects.[97]

These theories are somewhat related to the earlier theory of mind approach, which hypothesizes that autistic behavior arises from an inability to ascribe mental states to oneself and others. The theory of mind hypothesis is supported by autistic children's atypical responses to the Sally–Anne test for reasoning about others' motivations,[96] and the mirror neuron system theory of autism described in Pathophysiology maps well to the hypothesis.[83] However, most studies have found no evidence of impairment in autistic individuals' ability to understand other people's basic intentions or goals; instead, data suggests that impairments are found in understanding more complex social emotions or in considering others' viewpoints.[98]

The second category focuses on nonsocial or general processing. Executive dysfunction hypothesizes that autistic behavior results in part from deficits in working memory, planning, inhibition, and other forms of executive function.[99] Tests of core executive processes such as eye movement tasks indicate improvement from late childhood to adolescence, but performance never reaches typical adult levels.[100] A strength of the theory is predicting stereotyped behavior and narrow interests;[101] two weaknesses are that executive function is hard to measure[99] and that executive function deficits have not been found in young autistic children.[23]

Weak central coherence theory hypothesizes that a limited ability to see the big picture underlies the central disturbance in autism. One strength of this theory is predicting special talents and peaks in performance in autistic people.[102] A related theory—enhanced perceptual functioning—focuses more on the superiority of locally oriented and perceptual operations in autistic individuals.[103] These theories map well from the underconnectivity theory of autism.

Neither category is satisfactory on its own; social cognition theories poorly address autism's rigid and repetitive behaviors, while the nonsocial theories have difficulty explaining social impairment and communication difficulties.[59] A combined theory based on multiple deficits may prove to be more useful.[104]

Screening

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child's unusual behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months.[52] As postponing treatment may affect long-term outcome, any of the following signs is reason to have a child evaluated by a specialist without delay:

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving goodbye, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word spontaneous phrases (other than instances of echolalia) by 24 months.

- Any loss of any language or social skills, at any age.[17]

U.S. and Japanese practice is to screen all children for ASD at 18 and 24 months, using autism-specific formal screening tests. In contrast, in the UK, children whose families or doctors recognize possible signs of autism are screened. It is not known which approach is more effective.[2] Screening tools include the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire, and the First Year Inventory; initial data on M-CHAT and its predecessor CHAT on children aged 18–30 months suggests that it is best used in a clinical setting and that it has low sensitivity (many false-negatives) but good specificity (few false-positives).[52] It may be more accurate to precede these tests with a broadband screener that does not distinguish ASD from other developmental disorders.[105] Screening tools designed for one culture's norms for behaviors like eye contact may be inappropriate for a different culture.[106] Although genetic screening for autism is generally still impractical, it can be considered in some cases, such as children with neurological symptoms and dysmorphic features.[107]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on behavior, not cause or mechanism.[18][108] Autism is defined in the DSM-IV-TR as exhibiting at least six symptoms total, including at least two symptoms of qualitative impairment in social interaction, at least one symptom of qualitative impairment in communication, and at least one symptom of restricted and repetitive behavior. Sample symptoms include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with parts of objects. Onset must be prior to age three years, with delays or abnormal functioning in either social interaction, language as used in social communication, or symbolic or imaginative play. The disturbance must not be better accounted for by Rett syndrome or childhood disintegrative disorder.[1] ICD-10 uses essentially the same definition.[14]

Several diagnostic instruments are available. Two are commonly used in autism research: the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) is a semistructured parent interview, and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) uses observation and interaction with the child. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) is used widely in clinical environments to assess severity of autism based on observation of children.[20]

A pediatrician commonly performs a preliminary investigation by taking developmental history and physically examining the child. If warranted, diagnosis and evaluations are conducted with help from ASD specialists, observing and assessing cognitive, communication, family, and other factors using standardized tools, and taking into account any associated medical conditions.[109] A pediatric neuropsychologist is often asked to assess behavior and cognitive skills, both to aid diagnosis and to help recommend educational interventions.[110] A differential diagnosis for ASD at this stage might also consider mental retardation, hearing impairment, and a specific language impairment[109] such as Landau–Kleffner syndrome.[111] The presence of autism can make it harder to diagnose coexisting psychiatric disorders such as depression.[112]

Clinical genetics evaluations are often done once ASD is diagnosed, particularly when other symptoms already suggest a genetic cause.[46] Although genetic technology allows clinical geneticists to link an estimated 40% of cases to genetic causes,[113] consensus guidelines in the U.S. and UK are limited to high-resolution chromosome and fragile X testing.[46] A genotype-first model of diagnosis has been proposed, which would routinely assess the genome's copy number variations.[114] As new genetic tests are developed several ethical, legal, and social issues will emerge. Commercial availability of tests may precede adequate understanding of how to use test results, given the complexity of autism's genetics.[115] Metabolic and neuroimaging tests are sometimes helpful, but are not routine.[46]

ASD can sometimes be diagnosed by age 14 months, although diagnosis becomes increasingly stable over the first three years of life: for example, a one-year-old who meets diagnostic criteria for ASD is less likely than a three-year-old to continue to do so a few years later.[52] In the UK the National Autism Plan for Children recommends at most 30 weeks from first concern to completed diagnosis and assessment, though few cases are handled that quickly in practice.[109] A 2009 U.S. study found the average age of formal ASD diagnosis was 5.7 years, far above recommendations, and that 27% of children remained undiagnosed at age 8 years.[116] Although the symptoms of autism and ASD begin early in childhood, they are sometimes missed; years later, adults may seek diagnoses to help them or their friends and family understand themselves, to help their employers make adjustments, or in some locations to claim disability living allowances or other benefits.[117]

Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are problems in marginal cases, and much of the recent increase in the number of reported ASD cases is likely due to changes in diagnostic practices. The increasing popularity of drug treatment options and the expansion of benefits has given providers incentives to diagnose ASD, resulting in some overdiagnosis of children with uncertain symptoms. Conversely, the cost of screening and diagnosis and the challenge of obtaining payment can inhibit or delay diagnosis.[118] It is particularly hard to diagnose autism among the visually impaired, partly because some of its diagnostic criteria depend on vision, and partly because autistic symptoms overlap with those of common blindness syndromes or blindisms.[119]

Management

The main goals when treating children with autism are to lessen associated deficits and family distress, and to increase quality of life and functional independence. No single treatment is best and treatment is typically tailored to the child's needs.[9] Families and the educational system are the main resources for treatment.[2] Studies of interventions have methodological problems that prevent definitive conclusions about efficacy.[120] Although many psychosocial interventions have some positive evidence, suggesting that some form of treatment is preferable to no treatment, the methodological quality of systematic reviews of these studies has generally been poor, their clinical results are mostly tentative, and there is little evidence for the relative effectiveness of treatment options.[121] Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life can help children acquire self-care, social, and job skills,[9] and often improve functioning and decrease symptom severity and maladaptive behaviors;[122] claims that intervention by around age three years is crucial are not substantiated.[123] Available approaches include applied behavior analysis (ABA), developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, social skills therapy, and occupational therapy.[9] Educational interventions have some effectiveness in children: intensive ABA treatment has demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing global functioning in preschool children[124] and is well-established for improving intellectual performance of young children.[122] Neuropsychological reports are often poorly communicated to educators, resulting in a gap between what a report recommends and what education is provided.[110] It is not known whether treatment programs for children lead to significant improvements after the children grow up,[122] and the limited research on the effectiveness of adult residential programs shows mixed results.[125]

Many medications are used to treat ASD symptoms that interfere with integrating a child into home or school when behavioral treatment fails.[16][126] More than half of U.S. children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics.[127] Aside from antipsychotics,[128] there is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD.[129] A person with ASD may respond atypically to medications, the medications can have adverse effects,[9] and no known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments.[130] Experiments in mice have reversed or reduced some symptoms related to autism by replacing or modulating gene function after birth,[64] suggesting the possibility of targeting therapies to specific rare mutations known to cause autism.[63]

Although many alternative therapies and interventions are available, few are supported by scientific studies.[23][131] Treatment approaches have little empirical support in quality-of-life contexts, and many programs focus on success measures that lack predictive validity and real-world relevance.[24] Scientific evidence appears to matter less to service providers than program marketing, training availability, and parent requests.[132] Though most alternative treatments, such as melatonin, have only mild adverse effects[133] some may place the child at risk. A 2008 study found that compared to their peers, autistic boys have significantly thinner bones if on casein-free diets;[134] in 2005, botched chelation therapy killed a five-year-old child with autism.[135]

Treatment is expensive; indirect costs are more so. For someone born in 2000, a U.S. study estimated an average lifetime cost of $3.77 million (net present value in 2011 dollars, inflation-adjusted from 2003 estimate[136]), with about 10% medical care, 30% extra education and other care, and 60% lost economic productivity.[137] Publicly supported programs are often inadequate or inappropriate for a given child, and unreimbursed out-of-pocket medical or therapy expenses are associated with likelihood of family financial problems;[138] one 2008 U.S. study found a 14% average loss of annual income in families of children with ASD,[139] and a related study found that ASD is associated with higher probability that child care problems will greatly affect parental employment.[140] U.S. states increasingly require private health insurance to cover autism services, shifting costs from publicly funded education programs to privately funded health insurance.[141] After childhood, key treatment issues include residential care, job training and placement, sexuality, social skills, and estate planning.[142]

Prognosis

No cure is known.[2][9] Children recover occasionally, so that they lose their diagnosis of ASD;[143] this occurs sometimes after intensive treatment and sometimes not. It is not known how often recovery happens;[122] reported rates in unselected samples of children with ASD have ranged from 3% to 25%.[143] A few autistic children have acquired speech at age 5 or older.[144] Most children with autism lack social support, meaningful relationships, future employment opportunities or self-determination.[24] Although core difficulties tend to persist, symptoms often become less severe with age.[16] Few high-quality studies address long-term prognosis. Some adults show modest improvement in communication skills, but a few decline; no study has focused on autism after midlife.[145] Acquiring language before age six, having an IQ above 50, and having a marketable skill all predict better outcomes; independent living is unlikely with severe autism.[146] A 2004 British study of 68 adults who were diagnosed before 1980 as autistic children with IQ above 50 found that 12% achieved a high level of independence as adults, 10% had some friends and were generally in work but required some support, 19% had some independence but were generally living at home and needed considerable support and supervision in daily living, 46% needed specialist residential provision from facilities specializing in ASD with a high level of support and very limited autonomy, and 12% needed high-level hospital care.[11] A 2005 Swedish study of 78 adults that did not exclude low IQ found worse prognosis; for example, only 4% achieved independence.[147] A 2008 Canadian study of 48 young adults diagnosed with ASD as preschoolers found outcomes ranging through poor (46%), fair (32%), good (17%), and very good (4%); 56% of these young adults had been employed at some point during their lives, mostly in volunteer, sheltered or part-time work.[148] Changes in diagnostic practice and increased availability of effective early intervention make it unclear whether these findings can be generalized to recently diagnosed children.[8]

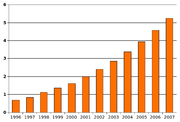

Epidemiology

Most recent reviews tend to estimate a prevalence of 1–2 per 1,000 for autism and close to 6 per 1,000 for ASD;[8] because of inadequate data, these numbers may underestimate ASD's true prevalence.[46] PDD-NOS's prevalence has been estimated at 3.7 per 1,000, Asperger syndrome at roughly 0.6 per 1,000, and childhood disintegrative disorder at 0.02 per 1,000.[149] The number of reported cases of autism increased dramatically in the 1990s and early 2000s. This increase is largely attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, referral patterns, availability of services, age at diagnosis, and public awareness,[149][150] though unidentified environmental risk factors cannot be ruled out.[6] The available evidence does not rule out the possibility that autism's true prevalence has increased;[149] a real increase would suggest directing more attention and funding toward changing environmental factors instead of continuing to focus on genetics.[65]

Boys are at higher risk for ASD than girls. The sex ratio averages 4.3:1 and is greatly modified by cognitive impairment: it may be close to 2:1 with mental retardation and more than 5.5:1 without.[8] Although the evidence does not implicate any single pregnancy-related risk factor as a cause of autism, the risk of autism is associated with advanced age in either parent, and with diabetes, bleeding, and use of psychiatric drugs in the mother during pregnancy.[151] The risk is greater with older fathers than with older mothers; two potential explanations are the known increase in mutation burden in older sperm, and the hypothesis that men marry later if they carry genetic liability and show some signs of autism.[36] Most professionals believe that race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background do not affect the occurrence of autism.[152]

Several other conditions are common in children with autism.[2] They include:

- Genetic disorders. About 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndrome,[153] and ASD is associated with several genetic disorders.[154]

- Mental retardation. The fraction of autistic individuals who also meet criteria for mental retardation has been reported as anywhere from 25% to 70%, a wide variation illustrating the difficulty of assessing autistic intelligence.[155] For ASD other than autism, the association with mental retardation is much weaker.[156]

- Anxiety disorders are common among children with ASD; there are no firm data, but studies have reported prevalences ranging from 11% to 84%. Many anxiety disorders have symptoms that are better explained by ASD itself, or are hard to distinguish from ASD's symptoms.[157]

- Epilepsy, with variations in risk of epilepsy due to age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder.[158]

- Several metabolic defects, such as phenylketonuria, are associated with autistic symptoms.[81]

- Minor physical anomalies are significantly increased in the autistic population.[159]

- Preempted diagnoses. Although the DSM-IV rules out concurrent diagnosis of many other conditions along with autism, the full criteria for ADHD, Tourette syndrome, and other of these conditions are often present and these comorbid diagnoses are increasingly accepted.[160]

- Sleep problems affect about two-thirds of individuals with ASD at some point in childhood. These most commonly include symptoms of insomnia such as difficulty in falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and early morning awakenings. Sleep problems are associated with difficult behaviors and family stress, and are often a focus of clinical attention over and above the primary ASD diagnosis.[161]

History

A few examples of autistic symptoms and treatments were described long before autism was named. The Table Talk of Martin Luther contains the story of a 12-year-old boy who may have been severely autistic.[162] According to Luther's notetaker Mathesius, Luther thought the boy was a soulless mass of flesh possessed by the devil, and suggested that he be suffocated.[163] The earliest well-documented case of autism is that of Hugh Blair of Borgue, as detailed in a 1747 court case in which his brother successfully petitioned to annul Blair's marriage to gain Blair's inheritance.[164] The Wild Boy of Aveyron, a feral child caught in 1798, showed several signs of autism; the medical student Jean Itard treated him with a behavioral program designed to help him form social attachments and to induce speech via imitation.[165]

The New Latin word autismus (English translation autism) was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1910 as he was defining symptoms of schizophrenia. He derived it from the Greek word autós (αὐτός, meaning self), and used it to mean morbid self-admiration, referring to "autistic withdrawal of the patient to his fantasies, against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance".[166]

The word autism first took its modern sense in 1938 when Hans Asperger of the Vienna University Hospital adopted Bleuler's terminology autistic psychopaths in a lecture in German about child psychology.[167] Asperger was investigating an ASD now known as Asperger syndrome, though for various reasons it was not widely recognized as a separate diagnosis until 1981.[165] Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital first used autism in its modern sense in English when he introduced the label early infantile autism in a 1943 report of 11 children with striking behavioral similarities.[30] Almost all the characteristics described in Kanner's first paper on the subject, notably "autistic aloneness" and "insistence on sameness", are still regarded as typical of the autistic spectrum of disorders.[59] It is not known whether Kanner derived the term independently of Asperger.[168]

Kanner's reuse of autism led to decades of confused terminology like infantile schizophrenia, and child psychiatry's focus on maternal deprivation led to misconceptions of autism as an infant's response to "refrigerator mothers". Starting in the late 1960s autism was established as a separate syndrome by demonstrating that it is lifelong, distinguishing it from mental retardation and schizophrenia and from other developmental disorders, and demonstrating the benefits of involving parents in active programs of therapy.[169] As late as the mid-1970s there was little evidence of a genetic role in autism; now it is thought to be one of the most heritable of all psychiatric conditions.[170] Although the rise of parent organizations and the destigmatization of childhood ASD have deeply affected how we view ASD,[165] parents continue to feel social stigma in situations where their autistic children's behaviors are perceived negatively by others,[171] and many primary care physicians and medical specialists still express some beliefs consistent with outdated autism research.[172]

The Internet has helped autistic individuals bypass nonverbal cues and emotional sharing that they find so hard to deal with, and has given them a way to form online communities and work remotely.[173] Sociological and cultural aspects of autism have developed: some in the community seek a cure, while others believe that autism is simply another way of being.[12][174]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) ed. 2000. ISBN 0890420254. Diagnostic criteria for 299.00 Autistic Disorder.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Levy SE, Mandell DS, Schultz RT. Autism. Lancet. 2009;374(9701):1627–38. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61376-3. PMID 19819542.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Johnson CP, Myers SM, Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1183–215. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2361. PMID 17967920. Lay summary: AAP, 2007-10-29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Abrahams BS, Geschwind DH. Advances in autism genetics: on the threshold of a new neurobiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(5):341–55. doi:10.1038/nrg2346. PMID 18414403.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM. The teratology of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23(2–3):189–99. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001. PMID 15749245.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Rutter M. Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(1):2–15. doi:10.1080/08035250410023124. PMID 15858952.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Vaccines and autism:

- Doja A, Roberts W. Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature. Can J Neurol Sci. 2006;33(4):341–6. PMID 17168158.

- Gerber JS, Offit PA. Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(4):456–61. doi:10.1086/596476. PMID 19128068. Lay summary: IDSA, 2009-01-30.

- Gross L. A broken trust: lessons from the vaccine–autism wars. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(5):e1000114. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000114. PMID 19478850. PMC 2682483.

- Paul R. Parents ask: am I risking autism if I vaccinate my children? J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(6):962–3. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0739-y. PMID 19363650.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Newschaffer CJ, Croen LA, Daniels J et al. The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders [PDF]. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:235–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. PMID 17367287.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Myers SM, Johnson CP, Council on Children with Disabilities. Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1162–82. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2362. PMID 17967921. Lay summary: AAP, 2007-10-29.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Stefanatos GA. Regression in autistic spectrum disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18(4):305–19. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9073-y. PMID 18956241.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):212–29. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. PMID 14982237.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Silverman C. Fieldwork on another planet: social science perspectives on the autism spectrum. Biosocieties. 2008;3(3):325–41. doi:10.1017/S1745855208006236.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Geschwind DH. Autism: many genes, common pathways? Cell. 2008;135(3):391–5. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.016. PMID 18984147.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 World Health Organization. F84. Pervasive developmental disorders; 2007 [cited 2009-10-10].

- ↑ Rogers SJ. What are infant siblings teaching us about autism in infancy? Autism Res. 2009;2(3):125–37. doi:10.1002/aur.81. PMID 19582867.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Rapin I, Tuchman RF. Autism: definition, neurobiology, screening, diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55(5):1129–46. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2008.07.005. PMID 18929056.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Filipek PA, Accardo PJ, Baranek GT et al. The screening and diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29(6):439–84. doi:10.1023/A:1021943802493. PMID 10638459. This paper represents a consensus of representatives from nine professional and four parent organizations in the U.S.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 London E. The role of the neurobiologist in redefining the diagnosis of autism. Brain Pathol. 2007;17(4):408–11. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00103.x. PMID 17919126.

- ↑ Sacks O. An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales. Knopf; 1995. ISBN 0679437851.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Volkmar F, Chawarska K, Klin A. Autism in infancy and early childhood. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:315–36. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070159. PMID 15709938. A partial update is in: Volkmar FR, Chawarska K. Autism in infants: an update. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):19–21. PMID 18458791.

- ↑ Sigman M, Dijamco A, Gratier M, Rozga A. Early detection of core deficits in autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10(4):221–33. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20046. PMID 15666338.

- ↑ Rutgers AH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, van Berckelaer-Onnes IA. Autism and attachment: a meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(6):1123–34. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00305.x. PMID 15257669.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Sigman M, Spence SJ, Wang AT. Autism from developmental and neuropsychological perspectives. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:327–55. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095210. PMID 17716073.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Burgess AF, Gutstein SE. Quality of life for people with autism: raising the standard for evaluating successful outcomes. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2007;12(2):80–6. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2006.00432.x.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Dominick KC, Davis NO, Lainhart J, Tager-Flusberg H, Folstein S. Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Res Dev Disabil. 2007;28(2):145–62. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2006.02.003. PMID 16581226.

- ↑ Långström N, Grann M, Ruchkin V, Sjöstedt G, Fazel S. Risk factors for violent offending in autism spectrum disorder: a national study of hospitalized individuals. J Interpers Violence. 2008;24(8):1358–70. doi:10.1177/0886260508322195. PMID 18701743.

- ↑ Noens I, van Berckelaer-Onnes I, Verpoorten R, van Duijn G. The ComFor: an instrument for the indication of augmentative communication in people with autism and intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50(9):621–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00807.x. PMID 16901289.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Landa R. Early communication development and intervention for children with autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(1):16–25. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20134. PMID 17326115.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Tager-Flusberg H, Caronna E. Language disorders: autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(3):469–81. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.02.011. PMID 17543905.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child. 1943;2:217–50. Reprinted in Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1968;35(4):100–36. PMID 4880460.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Williams DL, Goldstein G, Minshew NJ. Neuropsychologic functioning in children with autism: further evidence for disordered complex information-processing. Child Neuropsychol. 2006;12(4–5):279–98. doi:10.1080/09297040600681190. PMID 16911973.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Lam KSL, Aman MG. The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(5):855–66. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0213-z. PMID 17048092.

- ↑ Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: comparisons to mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):237–43. doi:10.1023/A:1005596502855. PMID 11055459.

- ↑ Treffert DA. The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1522):1351–7. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0326. PMID 19528017. Lay summary: Wisconsin Medical Society.

- ↑ Plaisted Grant K, Davis G. Perception and apperception in autism: rejecting the inverse assumption. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1522):1393–8. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0001. PMID 19528022.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 Geschwind DH. Advances in autism. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:367–80. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.053107.121225. PMID 19630577.

- ↑ Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S. Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(12):1255–68. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x. PMID 16313426.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger B, Gal E. A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(1):1–11. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3. PMID 18512135.

- ↑ Fournier KA, Hass CJ, Naik SK, Lodha N, Cauraugh JH. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-0981-3. PMID 20195737.

- ↑ Erickson CA, Stigler KA, Corkins MR, Posey DJ, Fitzgerald JF, McDougle CJ. Gastrointestinal factors in autistic disorder: a critical review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35(6):713–27. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0019-4. PMID 16267642.

- ↑ Buie T, Campbell DB, Fuchs GJ 3rd et al. Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in individuals with ASDs: a consensus report. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 1):S1–18. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1878C. PMID 20048083.

- ↑ Montes G, Halterman JS. Psychological functioning and coping among mothers of children with autism: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):e1040–6. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2819. PMID 17473077.

- ↑ Orsmond GI, Seltzer MM. Siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders across the life course [PDF]. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(4):313–20. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20171. PMID 17979200.

- ↑ Volkmar FR, State M, Klin A. Autism and autism spectrum disorders: diagnostic issues for the coming decade. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(1–2):108–15. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02010.x. PMID 19220594.

- ↑ Freitag CM. The genetics of autistic disorders and its clinical relevance: a review of the literature. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(1):2–22. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001896. PMID 17033636.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Caronna EB, Milunsky JM, Tager-Flusberg H. Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(6):518–23. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.115337. PMID 18305076.

- ↑ Piven J, Palmer P, Jacobi D, Childress D, Arndt S. Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families [PDF]. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(2):185–90. PMID 9016266.

- ↑ Happé F. Understanding assets and deficits in autism: why success is more interesting than failure [PDF]. Psychologist. 1999;12(11):540–7.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen S. The hyper-systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism [PDF]. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(5):865–72. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.010. PMID 16519981.

- ↑ Cohen D, Pichard N, Tordjman S et al. Specific genetic disorders and autism: clinical contribution towards their identification. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35(1):103–16. doi:10.1007/s10803-004-1038-2. PMID 15796126.

- ↑ Validity of ASD subtypes:

- Klin A. Autism and Asperger syndrome: an overview. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(suppl 1):S3–S11. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462006000500002. PMID 16791390.

- Witwer AN, Lecavalier L. Examining the validity of autism spectrum disorder subtypes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(9):1611–24. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0541-2. PMID 18327636.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Landa RJ. Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in the first 3 years of life. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(3):138–47. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0731. PMID 18253102.

- ↑ Ozonoff S, Heung K, Byrd R, Hansen R, Hertz-Picciotto I. The onset of autism: patterns of symptom emergence in the first years of life. Autism Res. 2008;1(6):320–328. doi:10.1002/aur.53. PMID 19360687.

- ↑ Altevogt BM, Hanson SL, Leshner AI. Autism and the environment: challenges and opportunities for research. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1225–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3000. PMID 18519493.

- ↑ Reiss AL. Childhood developmental disorders: an academic and clinical convergence point for psychiatry, neurology, psychology and pediatrics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(1-2):87–98. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02046.x. PMID 19220592.

- ↑ Piggot J, Shirinyan D, Shemmassian S, Vazirian S, Alarcón M. Neural systems approaches to the neurogenetics of autism spectrum disorders. Neuroscience. 2009;164(1):247–56. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.054. PMID 19482063.

- ↑ Stephan DA. Unraveling autism. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(1):7–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.003. PMID 18179879.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Happé F, Ronald A. The 'fractionable autism triad': a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18(4):287–304. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. PMID 18956240.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Happé F, Ronald A, Plomin R. Time to give up on a single explanation for autism. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(10):1218–20. doi:10.1038/nn1770. PMID 17001340.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Beaudet AL. Autism: highly heritable but not inherited. Nat Med. 2007;13(5):534–6. doi:10.1038/nm0507-534. PMID 17479094.

- ↑ Buxbaum JD. Multiple rare variants in the etiology of autism spectrum disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):35–43. PMID 19432386.

- ↑ Cook EH, Scherer SW. Copy-number variations associated with neuropsychiatric conditions. Nature. 2008;455(7215):919–23. doi:10.1038/nature07458. PMID 18923514.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Betancur C, Sakurai T, Buxbaum JD. The emerging role of synaptic cell-adhesion pathways in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(7):402–12. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.04.003. PMID 19541375.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Walsh CA, Morrow EM, Rubenstein JL. Autism and brain development. Cell. 2008;135(3):396–400. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.015. PMID 18984148.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Szpir M. Tracing the origins of autism: a spectrum of new studies. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(7):A412–8. PMID 16835042. PMC 1513312.

- ↑ Kinney DK, Munir KM, Crowley DJ, Miller AM. Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(8):1519–32. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.004. PMID 18598714.

- ↑ Penn HE. Neurobiological correlates of autism: a review of recent research. Child Neuropsychol. 2006;12(1):57–79. doi:10.1080/09297040500253546. PMID 16484102.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Amaral DG, Schumann CM, Nordahl CW. Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(3):137–45. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005. PMID 18258309.

- ↑ Müller RA. The study of autism as a distributed disorder. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(1):85–95. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20141. PMID 17326118.

- ↑ Casanova MF. The neuropathology of autism. Brain Pathol. 2007;17(4):422–33. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00100.x. PMID 17919128.

- ↑ Courchesne E, Pierce K, Schumann CM et al. Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron. 2007;56(2):399–413. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.016. PMID 17964254.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Schmitz C, Rezaie P. The neuropathology of autism: where do we stand? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34(1):4–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00872.x. PMID 17971078.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Persico AM, Bourgeron T. Searching for ways out of the autism maze: genetic, epigenetic and environmental clues. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(7):349–58. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.010. PMID 16808981.

- ↑ Südhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455(7215):903–11. doi:10.1038/nature07456. PMID 18923512.

- ↑ Kelleher RJ 3rd, Bear MF. The autistic neuron: troubled translation? Cell. 2008;135(3):401–6. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.017. PMID 18984149.

- ↑ Tuchman R, Moshé SL, Rapin I. Convulsing toward the pathophysiology of autism. Brain Dev. 2009;31(2):95–103. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2008.09.009. PMID 19006654.

- ↑ Ashwood P, Wills S, Van de Water J. The immune response in autism: a new frontier for autism research. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80(1):1–15. doi:10.1189/jlb.1205707. PMID 16698940.

- ↑ Stigler KA, Sweeten TL, Posey DJ, McDougle CJ. Autism and immune factors: a comprehensive review. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2009;3(4):840–60. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.01.007.

- ↑ Wills S, Cabanlit M, Bennett J, Ashwood P, Amaral D, Van de Water J. Autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1107:79–91. doi:10.1196/annals.1381.009. PMID 17804535.

- ↑ Hughes JR. A review of recent reports on autism: 1000 studies published in 2007. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(3):425–37. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.06.015. PMID 18627794.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Manzi B, Loizzo AL, Giana G, Curatolo P. Autism and metabolic diseases. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(3):307–14. doi:10.1177/0883073807308698. PMID 18079313.

- ↑ MNS and autism:

- Williams JHG. Self–other relations in social development and autism: multiple roles for mirror neurons and other brain bases. Autism Res. 2008;1(2):73–90. doi:10.1002/aur.15. PMID 19360654.

- Dinstein I, Thomas C, Behrmann M, Heeger DJ. A mirror up to nature. Curr Biol. 2008;18(1):R13–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.004. PMID 18177704.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Iacoboni M, Dapretto M. The mirror neuron system and the consequences of its dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(12):942–51. doi:10.1038/nrn2024. PMID 17115076.

- ↑ Frith U, Frith CD. Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing [PDF]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358(1431):459–73. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1218. PMID 12689373. PMC 1693139.

- ↑ Hamilton AFdC. Emulation and mimicry for social interaction: a theoretical approach to imitation in autism. Q J Exp Psychol. 2008;61(1):101–15. doi:10.1080/17470210701508798. PMID 18038342.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Powell K. Opening a window to the autistic brain. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(8):E267. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020267. PMID 15314667. PMC 509312.

- ↑ Di Martino A, Ross K, Uddin LQ, Sklar AB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Functional brain correlates of social and nonsocial processes in autism spectrum disorders: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(1):63–74. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.022. PMID 18996505.

- ↑ Broyd SJ, Demanuele C, Debener S, Helps SK, James CJ, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(3):279–96. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002. PMID 18824195.

- ↑ Chiu PH, Kayali MA, Kishida KT et al. Self responses along cingulate cortex reveal quantitative neural phenotype for high-functioning autism. Neuron. 2008;57(3):463–73. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.020. PMID 18255038. Lay summary: Technol Rev, 2007-02-07.

- ↑ Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ. Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: evidence from an FMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(4):951–61. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhl006. PMID 16772313.

- ↑ Murias M, Webb SJ, Greenson J, Dawson G. Resting state cortical connectivity reflected in EEG coherence in individuals with autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(3):270–3. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.012. PMID 17336944.

- ↑ Minshew NJ, Williams DL. The new neurobiology of autism: cortex, connectivity, and neuronal organization. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(7):945–50. doi:10.1001/archneur.64.7.945. PMID 17620483.

- ↑ Jeste SS, Nelson CA 3rd. Event related potentials in the understanding of autism spectrum disorders: an analytical review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(3):495–510. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0652-9. PMID 18850262.

- ↑ Roberts TP, Schmidt GL, Egeth M et al. Electrophysiological signatures: magnetoencephalographic studies of the neural correlates of language impairment in autism spectrum disorders. Int J Psychophysiol. 2008;68(2):149–60. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.01.012. PMID 18336941.

- ↑ Crespi B, Stead P, Elliot M (January 2010). "Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 Suppl 1: 1736–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906080106. PMID 19955444.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Baron-Cohen S. Autism: the empathizing–systemizing (E-S) theory [PDF]. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1156:68–80. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04467.x. PMID 19338503.

- ↑ Spelke ES. Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science?: a critical review [PDF]. Am Psychol. 2005;60(9):950–8. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.9.950. PMID 16366817.

- ↑ Hamilton AFdC. Goals, intentions and mental states: challenges for theories of autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(8):881–92. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02098.x. PMID 19508497.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Kenworthy L, Yerys BE, Anthony LG, Wallace GL. Understanding executive control in autism spectrum disorders in the lab and in the real world. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18(4):320–38. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9077-7. PMID 18956239.

- ↑ O'Hearn K, Asato M, Ordaz S, Luna B. Neurodevelopment and executive function in autism. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20(4):1103–32. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000527. PMID 18838033.

- ↑ Hill EL. Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8(1):26–32. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2004.01.001. PMID 14697400.

- ↑ Happé F, Frith U. The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36(1):5–25. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0. PMID 16450045.

- ↑ Mottron L, Dawson M, Soulières I, Hubert B, Burack J. Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36(1):27–43. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7. PMID 16453071.

- ↑ Rajendran G, Mitchell P. Cognitive theories of autism. Dev Rev. 2007;27(2):224–60. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2007.02.001.

- ↑ Wetherby AM, Brosnan-Maddox S, Peace V, Newton L. Validation of the Infant–Toddler Checklist as a broadband screener for autism spectrum disorders from 9 to 24 months of age. Autism. 2008;12(5):487–511. doi:10.1177/1362361308094501. PMID 18805944.

- ↑ Wallis KE, Pinto-Martin J. The challenge of screening for autism spectrum disorder in a culturally diverse society. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(5):539–40. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00720.x. PMID 18373717.

- ↑ Lintas C, Persico AM. Autistic phenotypes and genetic testing: state-of-the-art for the clinical geneticist. J Med Genet. 2009;46(1):1–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.060871. PMID 18728070. PMC 2603481.

- ↑ Baird G, Cass H, Slonims V. Diagnosis of autism. BMJ. 2003;327(7413):488–93. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7413.488. PMID 12946972. PMC 188387.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 Dover CJ, Le Couteur A. How to diagnose autism. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(6):540–5. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.086280. PMID 17515625.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Kanne SM, Randolph JK, Farmer JE. Diagnostic and assessment findings: a bridge to academic planning for children with autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18(4):367–84. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9072-z. PMID 18855144.

- ↑ Mantovani JF. Autistic regression and Landau–Kleffner syndrome: progress or confusion? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42(5):349–53. doi:10.1017/S0012162200210621. PMID 10855658.

- ↑ Matson JL, Neal D. Cormorbidity: diagnosing comorbid psychiatric conditions. Psychiatr Times. 2009;26(4).

- ↑ Schaefer GB, Mendelsohn NJ. Genetics evaluation for the etiologic diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Genet Med. 2008;10(1):4–12. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815efdd7. PMID 18197051. Lay summary: Medical News Today, 2008-02-07.

- ↑ Ledbetter DH. Cytogenetic technology—genotype and phenotype. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(16):1728–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMe0806570. PMID 18784093.

- ↑ McMahon WM, Baty BJ, Botkin J. Genetic counseling and ethical issues for autism. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C(1):52–7. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30082. PMID 16419100.

- ↑ Shattuck PT, Durkin M, Maenner M et al. Timing of identification among children with an autism spectrum disorder: findings from a population-based surveillance study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):474–83. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819b3848. PMID 19318992.

- ↑ National Autistic Society. Diagnosis: how can it benefit me as an adult?; 2005 [cited 2008-03-24].

- ↑ Shattuck PT, Grosse SD. Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(2):129–35. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20143. PMID 17563895.

- ↑ Cass H. Visual impairment and autism: current questions and future research. Autism. 1998;2(2):117–38. doi:10.1177/1362361398022002.

- ↑ Ospina MB, Krebs Seida J, Clark B et al. Behavioural and developmental interventions for autism spectrum disorder: a clinical systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(11):e3755. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003755. PMID 19015734. PMC 2582449.

- ↑ Krebs Seida J, Ospina MB, Karkhaneh M, Hartling L, Smith V, Clark B. Systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions for autism: an umbrella review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(2):95–104. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03211.x. PMID 19191842.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 122.2 122.3 Rogers SJ, Vismara LA. Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(1):8–38. doi:10.1080/15374410701817808. PMID 18444052.

- ↑ Howlin P, Magiati I, Charman T. Systematic review of early intensive behavioral interventions for children with autism. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;114(1):23–41. doi:10.1352/2009.114:23;nd41. PMID 19143460.

- ↑ Eikeseth S. Outcome of comprehensive psycho-educational interventions for young children with autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(1):158–78. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.02.003. PMID 18385012.

- ↑ Van Bourgondien ME, Reichle NC, Schopler E. Effects of a model treatment approach on adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33(2):131–40. doi:10.1023/A:1022931224934. PMID 12757352.

- ↑ Leskovec TJ, Rowles BM, Findling RL. Pharmacological treatment options for autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2008;16(2):97–112. doi:10.1080/10673220802075852. PMID 18415882.

- ↑ Oswald DP, Sonenklar NA. Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(3):348–55. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.17303. PMID 17630868.

- ↑ Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ. Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(1):6–14. doi:10.1172/JCI32483. PMID 18172517. PMC 2171144.

- ↑ Lack of research on drug treatments:

- Angley M, Young R, Ellis D, Chan W, McKinnon R. Children and autism—part 1—recognition and pharmacological management [PDF]. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(9):741–4. PMID 17915375.

- Broadstock M, Doughty C, Eggleston M. Systematic review of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2007;11(4):335–48. doi:10.1177/1362361307078132. PMID 17656398.

- ↑ Buitelaar JK. Why have drug treatments been so disappointing? Novartis Found Symp. 2003;251:235–44; discussion 245–9, 281–97. doi:10.1002/0470869380.ch14. PMID 14521196.

- ↑ Lack of support for interventions:

- Francis K. Autism interventions: a critical update [PDF]. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47(7):493–9. doi:10.1017/S0012162205000952. PMID 15991872.

- Levy SE, Hyman SL. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17(4):803–20, ix. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.004. PMID 18775371.

- Rao PA, Beidel DC, Murray MJ. Social skills interventions for children with Asperger's syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(2):353–61. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4. PMID 17641962.

- ↑ Stahmer AC, Collings NM, Palinkas LA. Early intervention practices for children with autism: descriptions from community providers. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2005;20(2):66–79. doi:10.1177/10883576050200020301. PMID 16467905.

- ↑ Angley M, Semple S, Hewton C, Paterson F, McKinnon R. Children and autism—part 2—management with complementary medicines and dietary interventions [PDF]. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(10):827–30. PMID 17925903.

- ↑ Hediger ML, England LJ, Molloy CA, Yu KF, Manning-Courtney P, Mills JL. Reduced bone cortical thickness in boys with autism or autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(5):848–56. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0453-6. PMID 17879151. Lay summary: NIH News, 2008-01-29.

- ↑ Brown MJ, Willis T, Omalu B, Leiker R. Deaths resulting from hypocalcemia after administration of edetate disodium: 2003–2005. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):e534–6. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0858. PMID 16882789.

- ↑ Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2008. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ↑ Ganz ML. The lifetime distribution of the incremental societal costs of autism. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(4):343–9. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.4.343. PMID 17404130. Lay summary: Harvard School of Public Health, 2006-04-25.

- ↑ Sharpe DL, Baker DL. Financial issues associated with having a child with autism. J Fam Econ Iss. 2007;28(2):247–64. doi:10.1007/s10834-007-9059-6.

- ↑ Montes G, Halterman JS. Association of childhood autism spectrum disorders and loss of family income. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e821–6. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1594. PMID 18381511.

- ↑ Montes G, Halterman JS. Child care problems and employment among families with preschool-aged children with autism in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e202–8. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3037. PMID 18595965.

- ↑ Reinke T. States increasingly mandate special autism services. Manag Care. 2008;17(8):35–6, 39. PMID 18777788.

- ↑ Aman MG. Treatment planning for patients with autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 10):38–45. PMID 16401149.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 Helt M, Kelley E, Kinsbourne M et al. Can children with autism recover? if so, how? Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18(4):339–66. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9075-9. PMID 19009353.