Australian English

Australian English (AusE, AuE, AusEng, en-AU[1]) is the form of the English language as spoken in Australia.

Contents |

Socio-historical linguistic context

Australian English began diverging from British English shortly after the foundation of the Australian penal colony of New South Wales in 1788. British convicts sent there, (including Cockneys from London[2]), came mostly from large English cities. They were joined by free settlers, military personnel and administrators, often with their families. However, a large part of the convict body were Irish, with at least 25% directly from Ireland, and others indirectly via Britain; estimates mention that possibly 60% of the convicts were Irish (citation needed). There were other populations of convicts from non-English speaking areas of Britain, such as the Welsh and Scots. English was not spoken, or was poorly spoken, by a large part of the convict population and the dominant English input was that of Cockney from South-East England.

In 1827 Peter Cunningham, in his book Two Years in New South Wales, reported that native-born white Australians of the time—known as "currency lads and lasses"[3]—spoke with a distinctive accent and vocabulary, with a strong Cockney influence. The transportation of convicts to Australia ended in 1868, but immigration of free settlers from Britain, Ireland and elsewhere continued.

The first of the Australian gold rushes, in the 1850s, began a much larger wave of immigration which would significantly influence the language. During the 1850s, when the UK was under economic hardship, about two per cent of its population emigrated to the Colony of New South Wales and the Colony of Victoria.[4]

Among the changes wrought by the gold rushes was "Americanisation" of the language—the introduction of words, spellings, terms, and usages from North American English. The words imported included some later considered to be typically Australian, such as dirt and digger.[5] Bonzer, which was once a common Australian slang word meaning "great", "superb" or "beautiful", is thought to have been a corruption of the American mining term bonanza,[6] which means a rich vein of gold or silver and is itself a loanword from Spanish. The influx of American military personnel in World War II brought further American influence; though most words were short-lived;[5] and only okay, you guys, and gee have persisted.[5]

Since the 1950s the American influence on language in Australia has mostly come from pop culture, the mass media (books, magazines and television programs), computer software and the internet. Some words, such as freeway and truck, have even been naturalised so completely that few Australians recognise their origin.[5]

One of the first writers to attempt renditions of Australian accents and vernacular was the novelist Joseph Furphy (a.k.a. Tom Collins), who wrote a popular account of rural New South Wales and Victoria during the 1880s, Such is Life (1903). C. J. Dennis wrote poems about working class life in Melbourne, such as The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke (1915), which was extremely popular and was made into a popular silent film (The Sentimental Bloke; 1919). John O'Grady's novel They're a Weird Mob has many examples of pseudo-phonetically written Australian speech in Sydney during the 1950s, such as "owyergoinmateorright?" ("How are you going, mate? All right?"). Thomas Keneally's novels set in Australia, particularly The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, frequently use vernacular such as "yair" for "yes" and "noth-think" for "nothing". Other books of note are "Let Stalk Strine" by Afferbeck Lauder – where "Strine" is "Australian" and "Afferbeck Lauder" is "alphabetical order" (the book is in alphabetical order) – and "How to be Normal in Australia" by Robert Treborlang[7].

British words such as mobile (phone) predominate in most cases. Some American, British and Australian variants exist side-by-side; in many cases – freeway, motorway (NSW) and highway (QLD), for instance – regional, social and ethnic variation within Australia typically defines word usage.[8]

Australian English is most similar to New Zealand English, due to their similar history and geographical proximity. Both use the expression different to (also encountered in British English, but not American) as well as different from, though with a semantic difference (different to highlights the "closeness" or "neutrality" of the difference, while different from highlights the difference).

Words of Irish origin are used, some of which are also common elsewhere in the Irish diaspora, such as bum for "backside" (Irish bun), tucker for "food", "provisions" (Irish tacar), as well as one or two native English words whose meaning have changed under Irish influence, such as paddock for "field", cf. Irish páirc, which has exactly the same meaning as the Australian paddock.

Australia adopted decimal currency in 1966 and the metric system in the 1970s. This, too has affected Australian English.[9][10]

Variation and changes

Three main varieties of Australian English are spoken according to linguists: Broad, General and Cultivated.[11] They are part of a continuum, reflecting variations in accent. They often, but not always, reflect the social class or educational background of the speaker.[12]

Broad Australian English is recognisable and familiar to English speakers around the world because it is used to identify Australian characters in non-Australian films and television programs (often in the somewhat artificial "stage" Australian English version). Examples are film/television personalities Steve Irwin and Paul Hogan. Slang terms Ocker, for a speaker, and Strine, a shortening of the word Australian for the dialect, are used in Australia.

The majority of Australians speak with the General Australian accent. This predominates among modern Australian films and television programs and is used by, for example, Eric Bana, Dannii Minogue and Hugh Jackman.

Cultivated Australian English has some similarities to British Received Pronunciation, and is often mistaken for it. Cultivated Australian English is spoken by some within Australian society, for example Cyril Ritchard and Judy Davis.

There are no strong variations in accent and pronunciation across different states and territories. Regional differences in pronunciation and vocabulary are small in comparison to those of the British and American English, and Australian pronunciation is determined less by region than by social, cultural and educational influences. There is some subtle regional variation. In Tasmania and Queensland, words such as "dance" and "grant" are usually heard with the older pronunciation of these words, using [æ:]. In South Australia, Western Australia, Victoria, and New South Wales [aː] is the norm. However, some speakers in those areas where [æ:]/[æ] is found prefer to use [a:] in such words as a sign of higher social class.[13] In words such as "pass", "can't", "last", all regional variants use [a:].

Phonology

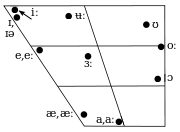

Australian English is a non-rhotic accent and it is similar to the other Southern Hemisphere accents (New Zealand English and South African English).[14] Like most dialects of English it is distinguished primarily by its vowel phonology.[15]

The vowels of Australian English can be divided into two categories: long and short vowels. The short vowels, consisting only of monophthongs, mostly correspond to the lax vowels used in analyses of Received Pronunciation. The long vowels, consisting of both monophthongs and diphthongs, mostly correspond to its tense vowels and centring diphthongs. Unlike most varieties of English, it has a phonemic length distinction: that compresses, shortens or removes these features.

- Many speakers have also coalesced /dj/, /sj/ and /tj/ into /dʒ/, /ʃ/ and /tʃ/, producing standard pronunciations such as [t͡ʃʰʉːn] for tune.

- t, dd and s in the combinations tr, dr and sr (this latter loan words only) also fall in with /dʒ/, /ʃ/ and /tʃ/ for many speakers, and for all speakers in the case of sr in loan words, thus tree /tʃɹᵊi:/, draw /dʒɹɔː/ and Sri Lanka /ʃɹi'læŋkə/.

- In colloquial speech intervocalic /t/ undergoes voicing and flapping to the alveolar tap [ɾ] after the stressed syllable and before unstressed vowels (as in butter, party) and syllabic /l/, though not before syllabic /n/ (bottle vs button [batn]), as well as at the end of a word or morpheme before any vowel (what else, whatever). In formal speech /t/ is retained. However, the alveolar flap is normally distinguishable by Australians from the intervocalic alveolar stop /d/, which is not flapped, thus ladder and latter, metal and medal, and coating and coding remain distinct; further, when coating becomes coatin' , the t remains voiceless, thus [kʌutn]. This is a quality that Australian English shares with some other varieties of English.

- Intervocalic /nt/ in fast speech can be realised as [n], another trait shared other varieties of English at the colloquial or dialect level, though in formal speech the full form /nt/ is retained. This makes winter and winner homophones in fast speech. 1999 was a great year for EFL teachers in Australia to illustrate this : "nineen-niny-nine".

Vocabulary

Australian English has many words that some consider unique to the language. One of the best known is outback, meaning a remote, sparsely populated area. Another is The Bush, meaning either a native forest or a country area in general. 'Bush' is a word of Dutch origin: 'Bosch'. However, both terms have been widely used in many English-speaking countries. Early settlers from England brought other similar words, phrases and usages to Australia. Many words used frequently by country Australians are, or were, also used in all or part of England, with variations in meaning. For example, creek in Australia, as in North America, means a stream or small river, whereas in the UK it means a small watercourse flowing into the sea; paddock in Australia means field, whereas in the UK it means a small enclosure for livestock; bush or scrub in Australia, as in North America, means a wooded area, whereas in England they are commonly used only in proper names (such as Shepherd's Bush and Wormwood Scrubs). Australian English and several British English dialects (for example, Cockney, Scouse, Glaswegian and Geordie) use the word mate.

The origins of other words are not as clear or are disputed. Dinkum (or "fair dinkum") can mean "true", "is that true?" or "this is the truth!” among other things, depending on context and inflection. It is often claimed that dinkum dates back to the Australian goldrushes of the 1850s, and that it is derived from the Cantonese (or Hokkien) ding kam, meaning, "top gold". But scholars give greater credence to the conjecture that it originated from the extinct East Midlands dialect in England, where dinkum (or dincum) meant "hard work" or "fair work", which was also the original meaning in Australian English.[16] The derivative dinky-di means 'true' or devoted: a 'dinky-di Aussie' is a 'true Australian'. However, this expression is limited to describing objects or actions that are characteristically Australian. The words dinkum or dinky-di and phrases like true blue are widely purported to be typical Australian sayings, even though they are more commonly used in jest or parody than as authentic slang.

Similarly, g'day, a stereotypical Australian greeting, is no longer synonymous with "good day" in other varieties of English and is never used as an expression for "farewell", as "good day" is in other countries. It is simply used as a greeting.

A few words of Australian origin are now used in other parts of the Anglosphere as well; among these are first past the post, to finalise, brownout, and the colloquialisms uni "university" and <part> short of a <whole> meaning stupid or crazy, (e.g. "a few bricks short of a load" or "a sandwich short of a picnic".)[17]

Influence of Australian Aboriginal languages

Some elements of Aboriginal languages and Torres Strait languages have been adopted by Australian English – mainly as names for places, flora and fauna (for example dingo) and local culture. Many such are localised, and do not form part of general Australia use, while others, such as kangaroo, boomerang, budgerigar, wallaby and so on have become international. Beyond that, little has been adopted into the wider language, except for some localised terms and slang. Some examples are cooee and hard yakka. The former is used as a high-pitched call, for attracting attention, (pronounced /kʉː.iː/) which travels long distances. Cooee is also a notional distance: if he's within cooee, we'll spot him. Hard yakka means hard work and is derived from yakka, from the Yagara/Jagara language once spoken in the Brisbane region. Also from there is the word bung, from the Sydney pidgin English (and ultimately from the Sydney Aboriginal language), and originally meaning "dead", and now meaning "broken" or "caused to be less than perfect", such as "a bung knee", which is a knee that does not work properly for whatever reason, such as stiffness, pain, arthritis, an accident, or something like that. A failed piece of equipment may be described as having bunged up or as "on the bung" or "gone bung".

This is not to be confused with the homynym bung (up) "stuff/block (up)" (a "bunged up" nose = a stuffy/blocked nose). Another example is: He bunged a potato up the exhaust pipe "He stuffed a potato up the exhaust pipe". This is a specialised use of bung "put, throw, chuck, pretend" - bung some clothes on and bung a steak in the barby, bung on an act (i.e. "pretend", but in a negative sense - a "false pretence"). Bunging it on means "pretending", whether this is to be hurt, or drunk, or laughing, or any action that is a deliberate pretence.

Although didgeridoo, referring to a well-known wooden musical instrument, is often thought of as an Aboriginal word, it is now believed to be an onomatopoeic word invented by English speakers. It has also been suggested that it may have an Irish or Scottish Gaelic derivation because the word dúdaire means "piper" in Gaelic, and dúdaire dubh [du:dɪrʲɪ du:] means 'black pipe player'.[18] Many towns or suburbs of Australia have also been influenced or named after Aboriginal words. The most well known example is the capital, Canberra named after a local language word meaning "meeting place".

Spelling

Australian spelling generally follows conventions of British English, though officially both British and American spelling conventions have equal legality/validity (reference needed). As in British spelling, the 'u' is retained in words such as honour and favour, except in the name of the Labor Party, while the -ise ending is used in words such as realise.

As in most English speaking countries, there is no official governmental regulator or overseer of correct spelling and grammar. Dictionaries such as the Macquarie Dictionary and the Australian Oxford Dictionary have provided a compendium of words and spellings, but often include variants of spellings for certain words regardless of their commonality. This can lead to confusion about what is correct or acceptable spelling in Australian English.

There was a widely held belief in Australia that controversies over spelling resulted from the "Americanisation" of Australian English; the influence of American English in the late 20th century, but the debate over spelling is much older. For example, a pamphlet entitled The So-Called "American Spelling", published in Sydney some time before 1901, argued that "there is no valid etymological reason for the preservation of the u in such words as honor, labor, etc.",[19] alluding to older British spellings which also used the -or ending. The pamphlet also claimed that "the tendency of people in Australasia is to excise the u, and one of the Sydney morning papers habitually does this, while the other generally follows the older form." Newspapers are not always a reliable guide to community preference and usage,[20] as they are often more concerned about saving space.[21] For example, circa 2007 Melbourne newspaper The Age finally changed its longstanding policy of omitting the u, in response to continuing complaints from its readers.[22] One of the two major political parties is the Australian Labor Party, spelt without a 'u', with the atypical spelling dating back to 1912 as what was then an attempt to "modernise" the name. The main champion of the spelling change was King O'Malley, a major figure in the party's early history, who publicly claimed to have been born in Canada but was most likely born in the U.S. and spent (almost) all of the first 30 years of his life in the U.S. It should also be noted that in its early years, the ALP was significantly influenced by the U.S. labour movement. The only word that is consistently spelt differently in Australian English to British English is "programme", which is spelt "program" in Australia as a direct result of American influence.

Colloquialisms

Diminutives are commonly used and are often used to indicate familiarity. Some common examples are arvo (afternoon), brekkie (breakfast), barbie (barbecue), sanger/sanga (sandwich),[23] snag/snagger (sausage),[23] smoko (smoking break), rellie (relative), Aussie (Australian) and pressie (present). The last two are pronounced /ˈɒzi/ and /ˈprɛzi/ respectively, never with a voiceless 's'.

This may also be done with people's names to create nicknames (other English speaking countries create similar diminutives). For example, "Gazza" from Gary.

Incomplete comparisons are sometimes used, such as "sweet as".

South Australia's use of the expression "heaps good" is famous among the other states of Australia. The expression is often used during South Australian tourism advertisements.

Litotes, such as "not bad", "not much" and "you're not wrong", are often used.

Many idiomatic phrases and words once common in Australian English are now stereotypes and caricatured exaggerations, and have disappeared from everyday use. Such outdated and occasionally parodied terms include strewth, you beaut and crikey, though many of these terms are still commonplace in rural areas such as the Wimmera.

Waltzing Matilda written by bush poet Banjo Paterson contains many obsolete Australian words and phrases that appeal to a rural ideal and are understood by Australians even though they are not in common usage outside the song. One example is the title, which means travelling, particularly with a swag.

See also

- Australian Aboriginal English

- Australian English vocabulary

- IPA chart for English dialects

- New Zealand English

- South African English

- Cockney English

- Australian Kriol language

- Strine

References

- ↑

en-AUis the language code for Australian English , as defined by ISO standards (see ISO 639-1 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-2) and Internet standards (see IETF language tag). - ↑ Moore, B 2008, Speaking our language: the story of Australian English, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, p. 69.

- ↑ Hughes, Robert. The Fatal Shore. London: Harvill (1986).

- ↑ Geoffrey Blainey, 1993, The Rush That Never Ended (4th ed.) Melbourne University Press

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Bell, R. Americanization and Australia. UNSW Press (1998).

- ↑ Robert J. Menner, "The Australian Language" American Speech, Vol. 21, No. 2 (April 1946), pp. 120

- ↑ Treborlang, Robert. How to be Normal in Australia: A Practical Guide to the Uncharted Territory of Antipodean Relationships. Major Mitchell Press, Sydney (1987).

- ↑ Oliver, Mackay and Rochecouste. 'The Acquisition of Colloquial Terms by Western Australian Primary School Children from Non-English Speaking Backgrounds' in Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 24:5 (2003), 413–430.

- ↑ http://www.fionalake.com.au/australian-american-words.html

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=NxHuNOvwt7wC&pg=PA30&lpg=PA30&dq=Australian+English+and+metrication&source=bl&ots=_phbsJFgk9&sig=yNG0L6XLfk9EU-TUyg6WNt6MGC8&hl=en&ei=FsZeS8CxKNigkQXYsJ33Cw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CBoQ6AEwBjgK#v=onepage&q=&f=false The Cambridge History of the English Language: 1776–1997 , By Richard M. Hogg, Suzanne Romaine, Norman Francis Blake, Roger Lass, R. W. Burchfield, page 30

- ↑ Robert Mannell, "Impressionistic Studies of Australian English Phonetics"

- ↑ Australia's unique and evolving sound Edition 34, 2007 (23 August 2007) – The Macquarie Globe

- ↑ Crystal, D. (1995). Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Trudgill, Peter and Jean Hannah. (2002). International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English, 4th ed. London: Arnold. ISBN 0-340-80834-9, p. 4.

- ↑ Harrington, J., F. Cox, and Z. Evans (1997). "An acoustic phonetic study of broad, general, and cultivated Australian English vowels". Australian Journal of Linguistics 17: 155–84. doi:10.1080/07268609708599550.

- ↑ Frederick Ludowyk, 1998, "Aussie Words: The Dinkum Oil On Dinkum; Where Does It Come From?" (0zWords, Australian National Dictionary Centre). Access date: 5 November 2007.

- ↑ The Oxford English Dictionary. [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]

- ↑ Dymphna Lonergan, 2002, "Aussie Words: Didgeridoo; An Irish Sound In Australia" (0zWords, Australian National Dictionary Centre). Access date: 5 November 2007.

- ↑ The So Called "American Spelling." Its Consistency Examined. pre-1901 pamphlet, Sydney, E. J. Forbes. Quoted by Annie Potts in this article

- ↑ "A bevan by any other name could be a bogan"; Don Woolford; The Age; 27 March 2002:

Given a choice between "colour" and "color", 95 per cent chose the former, surprising given that many newspapers drop the "u".

- ↑ designwrite.ca: The Serial Comma.

- ↑ Reported in the pages of The Age at the time. Precise date T.B.C. Compare also with Webster in Australia by James McElvenny: "[...] the Age newspaper used the reformed spellings up to the end of the 1990s."

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Macquarie Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1991

- Notes

- Mitchell, Alexander G., 1995, The Story of Australian English, Sydney: Dictionary Research Centre.

External links

- Australian National Dictionary Centre

- The Australian National Dictionary Online

- Australian Word Map at the ABC – documents regionalisms

- R. Mannell, F. Cox and J. Harrington (2009), An Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology, Macquarie University. Accessed 2009-11-08

- Macquarie Dictionary

- Aussie English for beginners – the origins, meanings and a quiz to test your knowledge at the National Museum of Australia.

- Ozwords, Free newsletter from the Australian National Dictionary Centre, which includes articles on Australian English

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||