Asceticism

- Ascetic redirects here. You might also be looking for acetic acid. The term should not be confused with aestheticism.

Asceticism (from the Greek: ἄσκησις, áskēsis, "exercise" or "training" in the sense of athletic training) describes a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from various sorts of worldly pleasures often with the aim of pursuing religious and spiritual goals. Some forms of Christianity (see especially: Monastic life) and the Indian religions (including yoga) teach that salvation and liberation involve a process of mind-body transformation effected by exercising restraint with respect to actions of body, speech, and mind. The founders and earliest practitioners of these religions (e.g. Buddhism, Jainism, the Christian desert fathers) lived extremely austere lifestyles refraining from sensual pleasures and the accumulation of material wealth. This is to be understood not as an eschewal of the enjoyment of life but a recognition that spiritual and religious goals are impeded by such indulgence.

Asceticism is closely related to the Christian concept of chastity and might be said to be the technical implementation of the abstract vows of renunciation. Those who practise ascetic lifestyles do not consider their practices virtuous in themselves but pursue such a lifestyle in order to encourage, or 'prepare the ground' for, mind-body transformation.

In the popular imagination, asceticism may be considered obsessive or even masochistic in nature. However, the askēsis enjoined by religion functions in order to bring about greater freedom in various areas of one's life (such as freedom from compulsions and temptations) and greater peacefulness of mind (with a concomitant increase in clarity and power of thought).

Contents |

Etymology

The adjective "ascetic" derives from the ancient Greek term askēsis (practice, training or exercise). Originally associated with any form of disciplined practice, the term ascetic has come to mean anyone who practices a renunciation of worldly pursuits to achieve higher intellectual and spiritual goals.

Askesis is a Greek Christian term; the practice of spiritual exercises; rooted in the philosophical tradition of antiquity. Originally introduced as the spiritual struggle of the Greek Orthodox Church as the style of life where meat, alcohol, sex, and ostentatious clothing are avoided, the term is now used in several other relations.

Sociological and psychological views

Early 20th century German sociologist Max Weber made a distinction between innerweltliche and ausserweltliche asceticism, which means (roughly) "inside the world" and "outside the world", respectively. Talcott Parsons translated these as "worldly" and "otherworldly" (some translators use "inner-worldly", but that has a different connotation in English and is probably not what Weber had in mind).

"Otherworldly" asceticism is practiced by people who withdraw from the world in order to live an ascetic life (this includes monks who live communally in monasteries, as well as hermits who live alone). "Worldly" asceticism refers to people who live ascetic lives but don't withdraw from the world.

Weber claimed that this distinction originated in the Protestant Reformation, but later became secularized, so the concept can be applied to both religious and secular ascetics. (See Talcott Parsons' translation of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, translator's note on Weber's footnote 9 in chapter 2.)

20th century American psychological theorist David McClelland suggested that worldly asceticism is specifically targeted against worldly pleasures that distract people from their calling, and may accept worldly pleasures that are not distracting. As an example, he pointed out that Quakers have historically objected to bright colored clothing, but that wealthy Quakers often made their drab clothing out of expensive materials. The color was considered distracting, but the materials were not. Amish groups use similar criteria to make decisions about which modern technologies to use and which to avoid.[1]

Religious motivation

Self-discipline and abstinence in some form and degree is a part of religious practice within many religious and spiritual traditions. A more dedicated ascetical lifestyle is associated particularly with monks, yogis or priests, but any individual may choose to lead an ascetic life. Shakyamuni Gautama (who left a more severe ascetism to seek a reasoned "middle way" of balanced life), Mahavir Swami, Anthony the Great (St. Anthony of the Desert), Francis of Assisi, and Mahatma Gandhi can all be considered ascetics. Many of these men left their families, possessions, and homes to live a mendicant life, and in the eyes of their followers demonstrated great spiritual attainment, or enlightenment.

Hinduism

Sadhus are known for the extreme forms of self-denial they occasionally practice. These include extreme acts of devotion to a deity or principle, such as vowing never to use one leg or the other, or to hold an arm in the air for a period of months or years. The particular types of asceticism involved vary from sect to sect, and from holy man to holy man.[2]

The Rig Veda describes non-Vedic Kesins (long-haired ascetics) and Munis (silent ones).[3][4] The Kesins are described as friends of Vayu, Rudra, the Gandharvas and the Apsaras.[5] There is also another story in the Rig Veda that Dhruva the son of Uttanapada (the son of Manu) performs penance, making him "one with Brahma."[6]

Sanyasa is one of the four stages of life in Hinduism.

The term "tapas" is used in the Rig Veda to connote the burning of desires.[7]

Keeping silence, even in times of verbal abuse was practiced by Hindu ascetics.[8]

Yajnavalkya also describes Brahmans as "Bhiksacaryas."[5]

Jainism

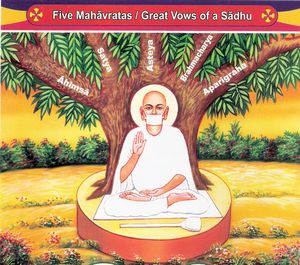

Asceticism, in one of its most intense forms, can be found in one of the oldest religions known as Jainism. Jainism encourages fasting, yoga practices, meditation in difficult postures, and other austerities.[9] According to Jains, one's highest goal should be Moksha (i.e., liberation from samsara, the cycle of birth and rebirth). For this, a soul has to be without attachment or self indulgence. This can be achieved only by the monks and nuns who take five great vows: of non-violence, of truth, of non-stealing, of non-possession and of celibacy. Most of the austerities and ascetic practices can be traced back to Vardhaman Mahavira, the twenty-fourth "fordmaker" or Tirthankara. The Acaranga Sutra, or Book of Good Conduct, is a sacred book within Jainism that discusses the ascetic code of conduct. Other texts that provide insight into conduct of ascetics include Yogashastra by Acharya Hemachandra and Niyamasara by Acharya Kundakunda. Other illustrious Jain works on ascetic conduct are Oghanijjutti, Pindanijjutti, Cheda Sutta, and Nisiha Suttafee.

Ascetic vows

As per the Jain vows, the monks and nuns renounce all relations and possessions. Jain ascetics practice complete nonviolence. Ahimsa is the first and foremost vow of a Jain ascetic. They do not hurt any living being, be it an insect or a human. They carry a special broom to sweep any insects that may cross their path. Some Jain monks wear a cloth over the mouth to prevent accidental harm to airborne germs and insects. They also do not use electricity as it involves violence. Furthermore, they do not use any devices or machines.

As they are possession-less and without any attachment, they travel from city to city, often crossing forests and deserts, and always barefoot. Jain ascetics do not stay in a single place for more than two months to prevent attachment to any place. However, during four months of monsoon (rainy season) known as chaturmaas, they continue to stay at a single place to avoid their killing life forms that thrive during the rains. Jain monks and nuns practice complete celibacy. They do not touch or share a sitting platform with a person of the opposite sex.

Dietary practices

Jain ascetics follow a strict vegetarian diet without root vegetables. Shvetambara monks do not cook food but solicit alms from householders. Digambara monks have only a single meal a day. Neither group will beg for food, but a Jain ascetic may accept a meal from a householder, provided that the latter is pure of mind and body and offers the food of his own volition and in the prescribed manner. During such an encounter, the monk remains standing and eats only a measured amount. Fasting (i.e., abstinence from food and sometimes water) is a routine feature of Jain asceticism. Fasts last for a day or longer, up to a month. Some monks avoid (or limit) medicine and/or hospitalisation out of disregard for the physical body.

Austerities and other daily practices

Other austerities include meditation in seated or standing posture near river banks in the cold wind, or meditation atop hills and mountains, especially at noon when the sun is at its fiercest. Such austerities are undertaken according to the physical and mental limits of the individual ascetic. Jain ascetics are (almost) completely without possessions. Some Jains (Shvetambara monks and nuns) own only unstitched white robes (an upper and lower garment) and a bowl used for eating and collecting alms. Male Digambara monks do not wear any clothes and carry nothing with them except a soft broom made of shed peacock feathers (pinchi) and eat from their hands. They sleep on the floor without blankets and sit on special wooden platforms.

Every day is spent either in study of scriptures or meditation or teaching to lay people. They stand aloof from worldly matters. Many Jain ascetics take a final vow of Santhara or Sallekhana (i.e., a peaceful and detached death where medicines, food, and water are abandoned). This is done when death is imminent or when a monk feels that he is unable to adhere to his vows on account of advanced age or terminal disease.

Quotes on ascetic practices from the Akaranga Sutra as Hermann Jacobi translated it[10][2]:

“A monk or a nun wandering from village to village should look forward for four cubits, and seeing animals they should move on by walking on his toes or heels or the sides of his feet. If there be some bypath, they should choose it, and not go straight on; then they may circumspectly wander from village to village. Third Lecture(6)”

'I shall become a Sramana who owns no house, no property, no sons, no cattle, who eats what others give him; I shall commit no sinful action; Master, I renounce to accept anything that has not been given.' Having taken such vows, (a mendicant) should not, on entering a village or scot-free town, &c., take himself, or induce others to take, or allow others to take, what has not been given. Seventh Lecture (1)

Buddhism

Theravada

The historical Siddhartha Gautama adopted an extreme ascetic life after leaving his father's palace, where he once lived in extreme luxury. But later the Shakyamuni rejected extreme asceticism because it is an impediment to ultimate freedom (nirvana) from suffering (samsara), choosing instead a path that met the needs of the body without crossing over into luxury and indulgence. After abandoning extreme asceticism he was able to achieve enlightenment. This position became known as the Madhyamaka or Middle Way, and became one of the central organizing principles of Theravadin philosophy.

The degree of moderation suggested by this middle path varies depending on the interpretation of Theravadism at hand. Some traditions emphasize ascetic life more than others.

The basic lifestyle of an ordained Theravadin practitioner (bhikkhu, monk; or bhikkhuni, nun) as described in the Vinaya Pitaka was intended to be neither excessively austere nor hedonistic. Monks and nuns were intended to have enough of life's basic requisites (particularly food, water, clothing, and shelter) to live safely and healthily, without being troubled by illness or weakness. While the life described in the Vinaya may appear difficult, it would be perhaps better described as Spartan rather than truly ascetic. Deprivation for its own sake is not valued. Indeed, it may be seen as a sign of attachment to one's own renunciation. The aim of the monastic lifestyle was to prevent concern for the material circumstances of life from intruding on the monk or nun's ability to engage in religious practice. To this end, having inadequate possessions was regarded as being no more desirable than having too many.

Initially, the Tathagata rejected a number of more specific ascetic practices that some monks requested to follow. These practices — such as sleeping in the open, dwelling in a cemetery or cremation ground, wearing only cast-off rags, etc. — were initially seen as too extreme, being liable to either upset the social values of the surrounding community, or as likely to create schisms among the Sangha by encouraging monks to compete in austerity. Despite their early prohibition, recorded in the Pali Canon, these practices (known as the Dhutanga practices, or in Thai as thudong) eventually became acceptable to the monastic community. They were recorded by Buddhaghosa in his Visuddhimagga, and later became significant in the practices of the Thai Forest Tradition.

Mahayana

The Mahayana traditions of Buddhism received a slightly different code of discipline than that used by the various Theravada sects. This fact, combined with significant regional and cultural variations, has resulted in differing attitudes towards asceticism in different areas of the Mahayana world. Particularly notable is the role that vegetarianism plays in East Asian Buddhism, particularly in China and Japan. While Theravada monks are compelled to eat whatever is provided for them by their lay supporters, including meat, Mahayana monks in East of Asia are most often vegetarian. This is attributable to a number of factors, including Mahayana-specific teachings regarding vegetarianism, East Asian cultural tendencies that predate the introduction of Buddhism (some of which may have their roots in Confucianism), and the different manner in which monks support themselves in East Asia. While Southeast Asian and Sri Lankan monks generally continue to make daily begging rounds to receive their daily meal, monks in East Asia more commonly receive bulk foodstuffs from lay supporters (or the funds to purchase them) and are fed from a kitchen located on the site of the temple or monastery, and staffed either by working monks or by lay supporters.

Similarly, divergent scriptural and cultural trends have brought a stronger emphasis on asceticism to some Mahayana practices. The Lotus Sutra, for instance, contains a story of a bodhisattva who burns himself as an offering to the assembly of all Buddhas in the world. This has become a patterning story for self-sacrifice in the Mahayana world, probably providing the inspiration for the self-immolation of the Vietnamese monk Thich Quang Duc during the 1960s, as well as several other incidents.

Judaism

The history of Jewish asceticism goes back thousands of years to the references of the Nazirite (Numbers 6) and the Wilderness Tradition that evolved out of the forty years in the desert. The prophets and their disciples were ascetic to the extreme including many examples of fasting and hermitic living conditions. After the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile and the prophetic institution was done away with a different form of asceticism arose when Antiochus IV Epiphanes threatened the Jewish religion in 167 BCE. The Hassidean sect attracted observant Jews to its fold and they lived as holy warriors in the wilderness during the war against the Seleucid Empire. With the rise of the Hasmoneans and finally Jonathan's claim to the High Priesthood in 152 BCE, the Essene sect separated under the Teacher of Righteousness and they took the banner of asceticism for the next two hundred years culminating in the Dead Sea Sect.

Asceticism is rejected by modern day Judaism; it is considered contrary to God's wishes for the world. God intended the world to be enjoyed, in a permitted context of course.[11]

However, Judaism does not encourage people to seek pleasure for its own sake but rather to do so in a spiritual way. An example would be thanking God for creating something enjoyable, like a wonderful view, or tasty food. As another example, while remembering that a person may be fulfilling the commandments of marriage and pru-urvu (procreation), sex should also be enjoyed. Food can be enjoyed by remembering that it is necessary to eat, but by thanking God for making it an enjoyable process, and by not overeating, or eating wastefully.

Modern normative Judaism is in opposition to the lifestyle of asceticism, and sometimes cast the Nazirite vow in a critical light. There did exist some ascetic Jewish sects in ancient times, most notably the Essenes and Ebionites. Some early Kabbalists may have, arguably, also held a lifestyle that could be regarded as ascetic.

Christianity

Different religious groups within Christianity have differing views on the subject of asceticism; the Catholic Church, as well as the Eastern Orthodox churches, Oriental Orthodox churches, and some Anglican churches, all see value in asceticism, while most of the Protestant denominations view asceticism generally in a negative light. One Christian context of asceticism is the liturgical season of Lent, the period between Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, leading up to Easter. During this season Catholics are counseled to practice prayer, fasting, especially on Fridays and special holy days, and charitable giving. Many other Christians also practice these traditional Lenten disciplines.

In the Christian Gospels, both the practice of asceticism, and also the enjoyment of the good things of the world are depicted, which seem to each have their proper time and place. John the Baptist, forerunner to Jesus, is depicted as a desert ascetic according to the image of an Old Testament Prophet "Clothed in camel's hair, with a leather belt around his waist. He fed on locusts and wild honey" (Mk 1:6). Jesus also is depicted as spending 40 days fasting in the desert and experiencing temptations prior to the beginning of his ministry (Lk 4 1-13). Later, Jesus is frequently depicted sharing and enjoying food and drink with his followers and others, including publicly known sinners, to the scandal of some people. Jesus' followers ask him about this: "They said to him, 'John's disciples often fast and pray, and so do the disciples of the Pharisees, but yours go on eating and drinking.' Jesus answered, 'Can you make the guests of the bridegroom fast while he is with them? But the time will come when the bridegroom will be taken from them; in those days they will fast'" (Lk 5:33-35). This has most often been interpreted to mean that after Jesus' death his followers will practice fasting, at least sometimes.

Catholic and Orthodox Christians have strongly tended to view Christian fasting, chastity and other ascetic practice as oriented toward desire and love for Christ (the "bridegroom" of the Church, still really present, these traditions believe, in the Eucharist) over and above all other things, even though the entire creation is affirmed as good. In Catholic theology this is expressed as an inseparable relationship between ascetical and mystical theology, as if the human and divine dimensions of living the Christian spiritual life of incarnate divine love, for instance as described by St. John of the Cross.

Protestant Christians vary widely in their attitudes toward and practices of asceticism. The Protestant reformers often strongly criticized monasticism and Catholic ascetical practices, contrasting these human works through which people participate in working out their salvation, with "faith alone" in Jesus as savior. Some Protestants are vehement about this to the point of rejecting the whole idea of asceticism, citing St. Paul's teaching in his epistle to the Romans that justification is by faith in Jesus rather than by works such as adherence to Jewish law, or similarly in 1 Timothy 4:2-3 speaks against those who would turn Christians away from true faith by imposing unnecessary religious rules: "liars with branded consciences.... forbid marriage and require abstinence from foods that God required to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and know the truth." However, many Protestants embrace "spiritual disciplines" such as fasting and disciplined dedication to prayer as a positive and Biblically based means of growth in the Christian life. The Lutheran Church encourages fasting during Lent, similar to the Roman Catholic teaching. Individuals in mainline Pentecostal denominations undertake both short and extended fasts as they believe the Holy Spirit leads them. For Charismatic Christians fasting is undertaken at the leading of God. Fasting is done in order to seek a closer intimacy with God, as well as an act of petition. Holiness movements, such as those started by John and Charles Wesley, and George Whitefield in the early days of Methodism, often practice such regular fasts as part of their regimen.

Saint Paul speaks of his own asceticism in his New Testament epistles, and also offers some nuance about true and false asceticism. For instance he writes of disciplining his body like an athlete, in order to subordinate it to reason in the service of the Gospel: "Athletes deny themselves all sorts of things. They do this to win a crown of leaves that wither, but we a crown that is imperishable" 1 Cor 9:25.

Asceticism within Catholic tradition includes spiritual disciplines practiced to work out the believer's salvation, and express one's repentance for sin, with the ultimate aim of purifying the heart and mind, by God's grace, for encounter with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, (see Kenosis). Although certain monks and nuns today such as those in the Roman Catholic religious orders of the Carthusians, and Cistercians, are known for especially strict acts of asceticism, even more rigorous ascetic practices were common in the early Church. The deserts of the middle-east were at one time said to have been inhabited by thousands of hermits[12] amongst whom St. Anthony the Great (aka St. Anthony of the Desert), St. Mary of Egypt, and a particularly unusual example is St. Simeon Stylites.

Christian authors of late antiquity such as Origen, Jerome[13], St. Ignatius[14], John Chrysostom, and Augustine interpreted meanings of Biblical texts within a highly asceticized religious environment. Scriptural examples of asceticism could be found in the lives of John the Baptist, Jesus, the twelve apostles and Saint Paul. The Dead Sea Scrolls revealed ascetic practices of the ancient Jewish sect of Essenes who took vows of abstinence to prepare for a holy war. Thus, the asceticism of practitioners like Jerome was hardly original (although some of his critics thought it was), and a desert ascetic like Antony the Great (251-356 CE) was in the tradition of ascetics in noted communities and sects of the previous centuries. Clearly, emphasis on an ascetic religious life was evident in both early Christian writings (see the Philokalia) and practices (see hesychasm). Other Christian followers of asceticism include individuals such as Simeon Stylites, Saint David of Wales, and Francis of Assisi. (See The Catholic Encyclopedia for a fuller discussion.) To the uninformed modern reader, early monastic asceticism may seem to be only about sexual renunciation. However, sexual abstinence was merely one aspect of ascetic renunciation. The ancient monks and nuns had other, equally weighty concerns: pride, humility, compassion, discernment, patience, judging others, prayer, hospitality, and almsgiving. For some early Christians, gluttony represented a more primordial problem than lust, and as such the reduced intake of food is also a facet of asceticism. As an illustration, the systematic collection of the Apophthegmata Patrum, or Sayings of the desert fathers and mothers has more than twenty chapters divided by theme; only one chapter is devoted to porneia ("sexual lust"). (See Elizabeth A. Clark. Reading Renunciation: Asceticism and Scripture in Early Christianity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999.)

Nowadays, the monastic state of Mount Athos, having a history of over a millennium, is a center of Christian spirituality and asceticism in Eastern Orthodox tradition.

Islam

The Islamic word for asceticism is zuhd.

The prophet Muhammad is quoted to have said, "What have I to do with worldly things? My connection with the world is like that of a traveler resting for a while underneath the shade of a tree and then moving on." He advised the people to live simple lives and himself practiced great austerities. Even when he had become the virtual king of Arabia, he lived an austere life bordering on privation. His wife Ayesha said that there was hardly a day in his life when he had two square meals (Muslim, Sahih Muslim, Vol.2, pg 198) taken from--[15]

"Asceticism is not that you should not own anything, but that nothing should own you." -Ali ibn Abi Talib[16]

Sufism

Sufism evolved not as a mystical but as an ascetic movement, as even the name suggests; the word Sufi may refer to a rough woolen robe of the ascetic. A natural bridge from asceticism to mysticism has often been crossed by Muslim ascetics. Through meditation on the Qur'an and praying to Allah, the Muslim ascetic believes that he draws near to Allah, and by leading an ascetic life paves the way for absorption in Allah, the Sufi way to salvation. (See Alfred Braunthal. Salvation and the Perfect Society. University of Massachusetts Press, 1979.)

Zoroastrianism

In Zoroastrianism, active participation in life through good thoughts, good words and good deeds is necessary to ensure happiness and to keep the chaos at bay. This active participation is a central element in Zoroaster's concept of free will, and Zoroastrianism rejects all forms of asceticism and monasticism.

Secular motivation

Examples of secular asceticism:

- A Starving Artist is someone who minimizes their living expenses in order to spend more time and effort on their art.

- Many professional athletes abstain from sex, rich foods, and other pleasures before major competitions in order to mentally prepare themselves for the upcoming contest.

- Straight Edge people abstain from alcohol, tobacco, drugs, and casual sex as part of a sub-culture lifestyle choice.

Religious versus secular motivation

The observation of an ascetic lifestyle can be found in both religious and secular settings. For example, practices based on a religious motivation might include fasting, abstention from sex, and other forms of self-denial intended to increase religious awareness or attain a closer relationship with a purported "divine". Non-religious (or not specifically religious) practices might be seen in such an example as Spartans undertaking regimens of severe physical discipline to prepare for battle.

Critics

In the third essay ("What Do Ascetic Ideals Mean?") from his book On the Genealogy of Morals, Friedrich Nietzsche discusses what he terms the "ascetic ideal" and its role in the formulation of morality along with the history of the will. In the essay, Nietzsche describes how such a paradoxical action as asceticism might serve the interests of life: through asceticism one can attain mastery over oneself. In this way one can express both ressentiment and the will to power. Nietzsche describes the morality of the ascetic priest as characterized by Christianity as one where, finding oneself in pain, one places the blame for the pain on oneself and thereby attempts and attains mastery over the world,[17] a technique which Nietzsche locates at the very origin of secular science as well as of religion.

See also

- Aesthetism (opposite)

- Arthur Schopenhauer

- Altruism

- Cynic

- Ctistae

- Decadence (usually opposite)

- Egoism (opposite)

- Epicureanism

- Fakir

- Fasting

- Flagellant

- Gustave Flaubert

- Hedonism (opposite)

- Hermit

- Lent

- Minimalism

- Monasticism

- Ramadan

- Rechabites

- Sensory deprivation

- Simple living

- Stoicism

References

- ↑ McClelland, The Achieving Society, 1961

- ↑ Rules and Regulations of Brahmanical Asceticism - Yatidharmasamuccaya of Yadava Prakasa/ Translated by Patrick Olivelle (Sri Satguru Publications/ Delhi) is a must-read book in this context.

- ↑ P. 77 An Introduction to Hinduism By Gavin D. Flood

- ↑ P. 137 The Rig Veda By Wendy Doniger, Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 P. 377 Classical Hinduism By Mariasusai Dhavamony

- ↑ P. 460 Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature By John McClintock, James Strong

- ↑ P. 34 India and the Greek world: a study in the transmission of culture By Jean W. Sedlar

- ↑ P. 134 The rule of Saint Benedict and the ascetic traditions from Asia to the West By Mayeul de Dreuille

- ↑ Frank William Iklé et al. "A History of Asia", page ?. Allyn and Bacon, 1964

- ↑ Hermann Jacobi, "Sacred Books of the East", vol. 22: Gaina Sutras Part I. 1884

- ↑ http://www.aish.com/literacy/judaism123/Five_Levels_of_Pleasure.asp

- ↑ for a study of the continuation of this early tradition in the Middle Ages, see Marina Miladinov, Margins of Solitude: Eremitism in Central Europe between East and West (Zagreb: Leykam International, 2008)

- ↑ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01767c.htm New Advent - Catholic Encyclopedia: Asceticism, quoting St. Jerome

- ↑ http://www.ellopos.net/notebook/ignatius.asp?pg=5 From Chapter 1 of a letter from Ignatius to Polycarp

- ↑ USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ The final sentence of the book puts it like this: "For man would rather will even nothingness than 'not will.'" (Kaufmann's trans.)

Further reading

- Valantasis, Richard. The Making of the Self: Ancient and Modern Asceticism. James Clarke & Co (2008) ISBN 978-0-227-17281-0.