Arvanitika

| Arvanitika | ||

|---|---|---|

| Arbërisht | ||

| Pronunciation | [aɾbəˈɾiʃt] | |

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Attica, Boeotia, South Euboea, Salamis Island; Thrace; Arkadia; Athens; Peloponnese; some villages in NW of Greece; N of island of Andros; 300 villages in total. | |

| Total speakers | 30,000 - 150,000 | |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

|

| Writing system | Greek alphabet (Arvanitic variant) Latin alphabet |

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | None | |

| ISO 639-2 | alb (B) | sqi (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | aat | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Arvanitika or Arvanitic (Arvanitika: αρbε̰ρίσ̈τ arbërisht, Greek: αρβανίτικα arvanitika) is the variety of Albanian traditionally spoken by the Arvanites, a population group in Greece. Arvanitika is today an endangered language, as its speakers have been shifting to the use of Greek and most younger members of the community no longer speak it.[1]

Contents |

Name

The name Arvanítika and its native equivalent Arbërishte [2] are derived from the ethnonym Arvanites, which in turn comes from the toponym Arbëna (Greek: Άρβανα), which in the Middle Ages referred to a region in what is today Albania (Babiniotis 1998). Its native equivalents (Arbërorë, Arbëreshë and others) formerly were the self-designation of Albanians in general. Both Arbëna and Albania/Albanian go further back to name forms attested since antiquity, and may be ultimately variants of the same root, although this is debated. In the past Arvanitika had sometimes been described as "Graeco-Albanian" and the like (e.g. Furikis, 1934), although today many Arvanites consider such names offensive, as they identify nationally and ethnically as Greeks and not Albanians.[3]

Classification

Arvanitika was brought to southern Greece during the late Middle Ages by settlers from what is today Albania. Arvanitika is also closely related to Arbëresh, the dialect of Albanian in Italy, which largely goes back to Arvanite settlers from Greece. Italian Arbëresh has retained some words borrowed from Greek (for instance haristis 'thank you', from ευχαριστώ; dhrom 'road', from δρόμος; Ne 'yes', from ναι, in certain villages). Italo-Arbëresh and Graeco-Arvanitika have a mutually intelligible vocabulary base, the unintelligible elements of the two dialects stem from the usage of Italian or Greek modernisms in the absence of native ones.

While linguistic scholarship unanimously describes Arvanitika as a dialect of Albanian[4] many Arvanites are reported to dislike the use of the name "Albanian" to designate it[3], as it carries the connotation of Albanian nationality and is thus felt to call their Greek identity into question.

Owing to its special social circumstances and ethnolinguistic identity, Arvanitika is currently listed as a separate entry ("Arvanitika Albanian", code "aat") in the draft international ISO 639-3 catalogue of language names[5], where it is categorised as part of an Albanian "macrolanguage"[6]. Similarly, the Ethnologue lists a separate sub-entry for "Albanian, Arvanitika" ([6]), along with parallel entries for Gheg Albanian, Tosk Albanian and Arbëresh[7]. There is no entry for Arvanitika in parts 1 and 2 of the international ISO 639 standard of language codes, which only has a single entry for Albanian (codes "alb", "sqi", or "sq").

Sociolinguistic work[8] has described Arvanitika within the conceptual framework of "ausbausprachen" and "abstandssprachen"[9]. In terms of "abstand" (objective difference of the linguistic systems), linguists' assessment of the degree of mutual intelligibility between Arvanitika and Standard Tosk range from fairly high[10] to only partial (Ethnologue). The Ethnologue also mentions that mutual intelligibility may even be problematic between different subdialects within Arvanitika. Mutual intelligibility between Standard Tosk and Arvanitika is higher than that between the two main dialect groups within Albanian, Tosk and Gheg. See below for a sample text in the three language forms. Trudgill (2004: 5) sums up that "[l]inguistically, there is no doubt that [Arvanitika] is a variety of Albanian".

In terms of "ausbau" (sociolinguistic "upgrading" towards an autonomous standard language), the strongest indicator of autonomy is the existence of a separate writing system, the Greek-based Arvanitic alphabet. A very similar system was formerly in use also by other Tosk Albanian speakers between the 16th and 18th century[11]. However, this script is very rarely used in practice today, as Arvanitika is almost exclusively a spoken language confined to the private sphere. There is also some disagreement amongst Arvanites (as with the Aromanians) as to whether the Latin alphabet should be used to write their language[3]. Spoken Arvanitika is internally richly diversified into sub-dialects, and no further standardization towards a common (spoken or written) Standard Arvanitika has taken place. At the same time, Arvanites do not use Standard Albanian as their standard language either, as they are generally not literate in the Latin-based standard Albanian orthography, and are not reported to use spoken-language media in Standard Albanian. In this sense, then, Arvanitika is not functionally subordinated to Standard Albanian as a dachsprache ("roof language"), in the way dialects of a national language within the same country usually are.

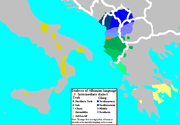

Geographic distribution

There are three main groups of Arvanitic settlements in Greece. Most Arvanites live in the south of Greece, across Attica, Boeotia, East Locris, the Peloponnese and some neighbouring areas and islands. A second, smaller group live in the northwest of Greece, in a zone contiguous with the Albanian-speaking lands proper. A third, outlying group is found in the northeast of Greece, in a few villages in Thrace.

According to some authors, the term "Arvanitika" in its proper sense applies only to the southern group [12] or to the southern and the Thracian groups together [13] i.e. to those dialects that have been separated from the core of Albanian for several centuries. The dialects in the northwest are reported to be more similar to neighbouring Tosk dialects within Albania and to the speech of the former Muslim Cham Albanians (Çamërishte), who used to live in the same region [14]. These dialects are classified by Ethnologue as part of core Tosk Albanian, as opposed to "Arvanitika Albanian" in the narrow sense, although Ethnologue notes that the term "Arvanitika" is also often applied indiscriminately to both forms in Greece[15]. In their own language, some groups in the north-west are reported to use the term Shqip (Albanian language) to refer to their own language as well as to that of Albanian nationals, and this has sometimes been interpreted as implying that they are ethnically Albanians[16].

The Arvanitika of southern Greece is richly sub-divided into local dialects. Sasse (1991) distinguishes as many as eleven dialect groups within that area: West Attic, Southeast Attic, Northeast-Attic-Boeotian, West Boeotian, Central Boeotian, Northeast Peloponnesian, Northwest Peloponnesian, South Peloponnesian, West Peloponnesian, Euboean, and Andriote.

Estimated numbers of speakers of Arvanitika vary widely, between 30,000 and 150,000. These figures include "terminal speakers" (Tsitsipis 1998) of the younger generation, who have only acquired an imperfect command of the language and are unlikely to pass it on to future generations. The number of villages with traditional Arvanite populations is estimated to 300. There are no monolingual Arvanitika-speakers, as all are today bilingual in Greek. Arvanitika is considered an endangered language due to the large-scale language shift towards Greek among the descendants of Arvanitika-speakers in recent decades.[17]

Characteristics

Arvanitika shares many features with the Tosk dialect spoken in Southern Albania. However, it has received a great deal of influence from Greek, mostly related to the vocabulary and the phonological system. At the same time, it is reported to have preserved some conservative features that were lost in mainstream Albanian Tosk. For example, it has preserved certain syllable-initial consonant clusters which have been simplified in Standard Albanian (cf. Arvanitika gljuhë IPA: [ˈɡljuhə] ('language/tongue'), vs. Standard Albanian gjuhë [ˈɟuhə]). In recent times, linguists have observed signs of accelerated structural convergence towards Greek and structural simplification of the language, which have been interpreted as signs of "language attrition", i.e. effects of impoverishment leading towards language death[18].

Writing system

Arvanitika has rarely been written. Reportedly (GHM 1995), it has been written in both the Greek alphabet (often with the addition of the letters b, d, e and j, or diacritics, e.g. [7]) and the Latin alphabet. Orthodox Tosk Albanians also used to write with a similar form of the Greek alphabet (e.g. [8]).

Language samples

Grammar

Source: Arvanitikos Syndesmos Ellados

Pronouns

| Personal pronouns | Possessive pronouns | |||

| 1Sg. | û | I | ími | mine |

| 2Sg. | ti | you | íti | yours |

| 3Sg.m. | ái | he | atía | his |

| 3Sg.f. | ajó | she | asája | hers |

| 1Pl. | ne | we | íni | ours |

| 2Pl. | ju | you | júai | yours |

| 3Pl.m. | atá | they (m.) | atíre | theirs (m.) |

| 3Pl.f. | ató | they (f.) | atíre | theirs (f.) |

Verb paradigms

| The verb HAVE | The verb BE | |||||||

| Pres. | Imperf. | Subj.Impf. | Subj.Perf. | Pres. | Imperf. | Subj.Impf. | Subj.Perf. | |

| 1Sg. | kam | keshë | të kem | të keshë | jam | jeshë | të jem | të jeshë |

| 2Sg. | ke | keshe | të kesh | të keshe | je | jeshe | të jesh | të jëshe |

| 3Sg. | ka | kish | të ket | të kish | ishtë, është | ish | të jet | të ish |

| 1Pl. | kemi | keshëm | të kemi | te keshëm | jemi | jeshëm | të jeshëm | të jeshëm |

| 2Pl. | kine | keshëtë | të kini | te keshëtë | jini | jeshëtë | të jeshëtë | të jeshëtë |

| 3Pl, | kanë | kishnë | të kenë | të kishnë | janë | ishnë | të jenë | të ishnë |

Comparison with other forms of Albanian

Compared with Standard Tosk Albanian (second row),

Source: Η Καινή Διαθήκη στα Αρβανίτικα; "Christus Rex" website |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Some common phrases

Source: Arvanitikos Syndesmos Ellados

| Flet fare arbërisht? | Do you speak Arvanitika at all? |

| Flas shumë pak. | I speak very little. |

| Je mirë? | Are you well? |

| Jam shumë mirë. | I am very well. |

| Çë bën, je mir? | How do you do?. |

| Si jam? Shum mir. | How am I doing? Very well, thanks. |

| Ti si je? | What about you? |

| Edhé u jam shum mir. | I'm fine, too. |

| Si ishtë it at? | How is your father? |

| Edhé aj isht shum mir. | He's doing fine. |

| Thuai të faljtura. | Give him my best regards. |

| Gruaja jote si ishtë? | How about your wife? |

| Nani edhe ajo, ishtë mir, i shkoi sëmunda çë kej. | Now she too is ok, the sickness is over. |

| T'i thuash tët atë, po do, të vemi nestrë të presmë dru, të më mar në telefon. | Tell your father, if he wants to go tomorrow to cut wood let him call me in the phone. |

Footnotes

- ↑ Babiniotis, Lexicon of the Greek Language

- ↑ Misspelled as Arberichte in the Ethnologue report, and in some other sources based on that.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 GHM 1995

- ↑ E.g. Haebler (1965); Trudgill (1976/77); Sasse (1985, 1991); Breu (1990); Furikis (1934), Babiniotis (1985: 41).

- ↑ ISO 639 code sets

- ↑ an intermediate category between a language family on the one hand and a single language with dialects on the other. According to [1] "macrolanguages" are defined as "clusters of closely-related language varieties that [...] can be considered individual languages, yet in certain usage contexts a single language identity for all is needed". This applies in "a transitional socio-linguistic situation in which sub-communities of a single language community are diverging, creating a need for some purposes to recognize distinct languages while, for other purposes, a single common identity is still valid".

- ↑ [2]?

- ↑ For detailed sociolinguistic studies of Arvanite speech communities, see Trudgill/Tzavaras 1977; Tsitsipis 1981, 1983, 1995, 1998; Banfi 1996, Botsi 2003.

- ↑ Trudgill 2004, citing the conceptual framework introduced by Kloss (1967).

- ↑ Trudgill 2004: 5, Botsi 2003

- ↑ [3], [4]

- ↑ Botsi 2003: 21

- ↑ Gordon 2005

- ↑ Euromosaic 1996

- ↑ Gordon 2005

- ↑ GHM 1995, quoting Banfi 1994

- ↑ Salminen (1993) lists it as "seriously endangered" in the Unesco Red Book of Endangered Languages. ([5]). See also Sasse (1992) and Tsitsipis (1981).

- ↑ Trudgill 1976/77; Thomason 2001, quoting Sasse 1992

References

- Babiniotis, Georgios (1985): Συνοπτική Ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσας με εισαγωγή στην ιστορικοσυγκριτική γλωσσολογία. ["A concise history of the Greek language, with an introduction to historical-comparative linguistics] Athens: Ellinika Grammata.

- Babiniotis, Georgios (1998), Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας ["Dictionary of Modern Greek"]. Athens: Kentro Lexikologias.

- Banfi, Emanuele (1994): "Minorités linguistiques en Grèce: Langues cachées, idéologie nationale, religion." ["Linguistic minorities in Greece: Hidden languages, national ideology, religion."] Paper presented at the Mercator Program Seminar at the Maison des Sciences de l’ Homme, on 6 June 1994, in Paris.

- Banfi, Emanuele (1996), "Minoranze linguistiche in Grecia: problemi storico- e sociolinguistici" ["Linguistic minorities in Greece: Historical and sociolinguistic problems"]. In: C. Vallini (ed.), Minoranze e lingue minoritarie: convegno internazionale. Naples: Universtario Orientale. 89-115.

- Botsi, Eleni (2003): Die sprachliche Selbst- und Fremdkonstruktion am Beispiel eines arvanitischen Dorfes Griechenlands: Eine soziolinguistische Studie. ("Linguistic construction of the self and the other in an Arvanite village in Greece: A sociolinguistic study"). PhD dissertation, University of Konstanz, Germany. Online text

- Breu, Walter (1990): "Sprachliche Minderheiten in Italien und Griechenland." ["Linguistic minorities in Italy and Greece"]. In: B. Spillner (ed.), Interkulturelle Kommunikation. Frankfurt: Lang. 169-170.

- Euromosaic (1996): "L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce". Report published by the Institut de Sociolingüística Catalana. Online version

- Furikis, Petros (1934): "Η εν Αττική ελληνοαλβανική διάλεκτος". ["The Greek-Albanian dialect in Attica"] Αθήνα 45: 49-181.

- GHM (=Greek Helsinki Monitor) (1995): "Report: The Arvanites". Online report

- Gordon, Raymond G. (ed.) (2005): Ethnologue: Languages of the world. 15th edition. Dallas: SIL International. Online database

- Haebler, Claus (1965): Grammatik der albanischen Mundarten von Salamis. ["Grammar of the Albanian dialects of Salamis"]. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz.

- Hammarström, Harald (2005): Review of Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th Edition. LINGUIST List 16.2637 (5 Sept 2005). Online article

- Joseph, Brian D. "Comparative perspectives on the place of Arvanitika within Greece and the Greek environment", 1999, pp. 208–214 in L. Tsitsipis (ed.), Arvanitika ke Elinika: Zitimata Poliglosikon ke Polipolitismikon Kinotiton Vol. II. Livadia: Exandas, 1999 PDF.

- Η Καινή Διαθήκη στα Αρβανίτικα: Διάτα ε Ρε ['The New Testament in Arvanitika']. Athens: Ekdoseis Gerou. No date.

- Kloss, Heinz (1967): "Abstand-languages and Ausbau-languages". Anthropological linguistics 9.

- Salminen, Tapani (1993–1999): Unesco Red Book on Endangered Languages: Europe. [9].

- Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1985): "Sprachkontakt und Sprachwandel: Die Gräzisierung der albanischen Mundarten Griechenlands" ["Language contact and language change: The Hellenization of the Albanian dialects of Greece"]. Papiere zur Linguistik 32(1). 37-95.

- Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1991): Arvanitika: Die albanischen Sprachreste in Griechenland. ["Arvanitika: The Albanian language relics in Greece"]. Wiesbaden.

- Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1992): "Theory of language death". In: M. Brenzinger (ed.), Language death: Factual and theoretical explorations with special reference to East Africa. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 7-30.

- Sella-Mazi, Eleni (1997): "Διγλωσσία και ολιγώτερο ομιλούμενες γλώσσες στην Ελλάδα" ["Diglossia and lesser-spoken languages in Greece"]. In: K. Tsitselikis, D. Christopoulos (eds.), Το μειονοτικό φαινόμενο στην Ελλάδα ["The minority phenomenon in Greece"]. Athens: Ekdoseis Kritiki. 349-413.

- Strauss, Dietrich (1978): "Scots is not alone: Further comparative considerations". Actes du 2e Colloque de Language et de Litterature Ecossaises, Strasbourg 1978. 80-97.

- Thomason, Sarah G. (2001): Language contact: An introduction. Washington: Georgetown University Press. Online chapter

- Trudgill, Peter (1976–77): "Creolization in reverse: reduction and simplification in the Albanian dialects of Greece", Transactions of the Philological Society, 32-50.

- Trudgill, Peter (2004): "Glocalisation [sic] and the Ausbau sociolinguistics of modern Europe". In: A. Duszak, U. Okulska (eds.), Speaking from the margin: Global English from a European perspective. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Online article

- Trudgill, Peter, George A. Tzavaras (1977): "Why Albanian-Greeks are not Albanians: Language shift in Attika and Biotia." In: H. Giles (ed.), Language, ethnicity and intergroup relations. London: Academic Press. 171-184.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1981): Language change and language death in Albanian speech communities in Greece: A sociolinguistic study. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1983): "Language shift among the Albanian speakers of Greece." Anthropological Linguisitcs 25(3): 288-308.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1995): "The coding of linguistic ideology in Arvanitika (Albanian): Language shift, congruent and contradictory discourse." Anthropological Linguistics 37: 541-577.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1998a): Αρβανίτικα και Ελληνικά: Ζητήματα πολυγλωσσικών και πολυπολιτισμικών κοινοτήτων. ["Arvanitika and Greek: Issues of multilingual and multicultural communities"]. Vol. 1. Livadeia.

- Tsitsipis, Lukas (1998b): A Linguistic Anthropology of Praxis and Language Shift: Arvanitika (Albanian) and Greek in Contact. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-823731-6. (Review by Alexander Rusakov on Linguist List.)

- The bilingual New Testament: Η Καινή Διαθήκη του Κυρίου και Σωτήρος ημών Ιησού Χριστού Δίγλωττος τουτέστι Γραικική και Αλβανιτική. Dhjata e re e Zotit sonë që na shpëtoi, Iisu Hrishtoit mbë di gjuhë, do me thënë gërqishte e dhe shqipëtarçe. Επιστασία Γρηγορίου Αρχιεπισκόπου της Ευβοίας. Κορφοί. Εν τη τυπογραφία της Διοικήσεως. 1827

External links

- Arvanitika Albanian at Ethnologue

- UNESCO's entry on Arvanitika Albanian

- Arvanitic dialogues - Arvanite League of Greece (in Arvanitika and in Greek)

- Study on the third person pronoun of Arvanitika by Panayotis D. Kupitoris, 24 March 1989

- Noctes Pelasgicae vel Symbolae ad cognoscendas dialectos Graeciae Pelasgicas collatae / Cura Dr. Caroli Heinrici Theodori Reinhold; in *.pdf format

- Die Nutzpflanzen Griechenlands by Theodor von Heldreich

- "Musings of a Terminal Speaker" - an article by Peter Constantine in Words Without Borders.