Arius

Arius (AD 250 or 256 – 336) was a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. His teachings about the nature of the Godhead, which emphasized the Father's Divinity over the Son, and his opposition to the Athanasian or Trinitarian Christology, made him a controversial figure in the First Council of Nicea, convened by Roman Emperor Constantine in 325 A.D. After Emperor Constantine legalized and formalized the Christianity of the time in the Roman Empire, the newly recognized Catholic Church sought to unify theology. Trinitarian partisans, including Athanasius, used Arius and Arianism as epithets to represent disagreement with co-equal Trinitarianism, a Christology representing the Father and Son (Jesus of Nazareth) as "of one essence" (consubstantial) and coeternal.[1]

Although virtually all positive writings on Arius' theology have been suppressed or destroyed[2], negative writings describe Arius' theology as one in which there was a time before the Son of God, where only God the Father existed. Despite concerted opposition, 'Arian', or nontrinitarian Christian churches persisted throughout Europe and North Africa, in various Gothic and Germanic kingdoms, until suppressed by military conquest or voluntary royal conversion between the fifth and seventh centuries.

Although "Arianism" suggests that Arius was the originator of the teaching that bears his name, the debate over the Son’s precise relationship to the Father did not begin with him. This subject had been discussed for decades before his advent; Arius merely intensified the controversy and carried it to a Church-wide audience, where other "Arians" such as Eusebius of Nicomedia and Eusebius of Caesarea would prove much more influential in the long run. In fact, some later "Arians" disavowed that moniker, claiming not to have been familiar with the man or his specific teachings.[3] However, because the conflict between Arius and his foes brought the issue to the theological forefront, the doctrine he proclaimed—though not originated by him—is generally labeled as "his".

Contents |

Early life and personality

Reconstructing the life and doctrine of Arius has proven to be a difficult task, as none of his original writings survive. Emperor Constantine ordered their burning while Arius was still living,[4] and any that survived this purge were later destroyed by his Orthodox opponents. Those works which have survived are quoted in the works of churchmen who denounced him as a heretic. This leads some—but not all—scholars to question their reliability.[5]

Arius was possibly of Libyan descent. His father's name is given as Ammonius. Arius is believed to have been a student at the exegetical school in Antioch, where he studied under Saint Lucian.[6] Having returned to Alexandria, Arius sided with Meletius of Lycopolis in his dispute over the readmission of those who had denied Christianity under fear of Roman torture, and was ordained a deacon under the latter's auspices. He was excommunicated by Bishop Peter of Alexandria in 311 for supporting Meletius,[7] but under Peter's successor Achillas, Arius was readmitted to communion and in 313 made presbyter of the Baucalis district in Alexandria.

Although his character has been severely assailed by his opponents, Arius appears to have been a man of personal ascetic achievement, pure morals, and decided convictions. Paraphrasing Epiphanius of Salamis, an opponent of Arius, Catholic historian Warren H. Carroll describes him as "tall and lean, of distinguished appearance and polished address. Women doted on him, charmed by his beautiful manners, touched by his appearance of asceticism. Men were impressed by his aura of intellectual superiority."[8]

Arius was accused of being too liberal in his theology and too "loose" with heresy (as defined by his opponents). However, some historians argue that Arius was actually quite conservative,[1] and that he deplored how, in his view, Christian theology was being too freely mixed with Greek paganism.[9]

The Arian controversy

Arius is notable primarily because of his role in the Arian controversy, a great fourth-century theological conflict that rocked the Christian world and led to the calling of the first ecumenical council of the Church. This controversy centered upon the nature of the Son of God, and his precise relationship to God the Father.

Beginnings

The historian Socrates of Constantinople reports that Arius ignited the controversy that bears his name when St. Alexander of Alexandria, who had succeeded Achillas as the Bishop of Alexandria, gave a sermon on the similarity of the Son to the Father. Arius interpreted Alexander's speech as being a revival of Sabellianism, condemned it, and then argued that "if the Father begat the Son, he that was begotten had a beginning of existence: and from this it is evident, that there was a time when the Son was not. It therefore necessarily follows, that he [the Son] had his substance from nothing."[10] This quote describes the essence of Arius' doctrine.

It is believed that Arius was influenced in his thinking by the teachings of Lucian of Antioch, a celebrated Christian teacher and martyr. In a letter to Patriarch Alexander of Constantinople Arius' bishop, Alexander of Alexandria, wrote that Arius derived his theology from Lucian. The express purpose of Alexander's letter was to complain of the doctrines that Arius was diffusing, but his charge of heresy against Arius is vague and unsupported by other authorities. Furthermore, Alexander's language, like that of most controversialists in those days, is quite vituperative. Moreover, even Alexander never accused Lucian of having taught Arianism; rather, he accused Lucian ad invidiam of heretical tendencies—which apparently, according to him, were transferred to his pupil, Arius.[11] The noted Russian historian Alexander Vasiliev refers to Lucian as "the Arius before Arius".[11]

Origen and Arius

Like many third-century Christian scholars, Arius was influenced by the writings of Origen, widely regarded as the first great theologian of Christianity.[12] However, while he drew support from Origen's theories on the Logos, the two did not agree on everything. Arius clearly argued that there was a time when the Son did not exist, and that the Logos had a beginning. By way of contrast, Origen taught that the relation of the Son to the Father had no beginning.[13]

Arius objected to Origen's doctrine, complaining about it in his letter to the Nicomedian Eusebius, who had also studied under Lucian. Nevertheless, despite disagreeing with Origen on this point, Arius found solace in his writings, which used expressions that favored Arius's contention that the Logos was of a different substance than the Father, and owed his existence to his Father's will. However, because Origen's theological speculations were often proffered to stimulate further inquiry rather than to put an end to any given dispute, both Arius and his opponents were able to invoke the authority of this revered (at the time) theologian during their debate.[14]

Initial responses

At first, Bishop Alexander seemed unsure of what to do about Arius. The question that Arius was raising had been left unsettled two generations previously; if in any sense it could be said to have been decided, it had been settled in favor of opponents of the homoousion (the idea that the Father, Son and Holy Ghost are of the same exact substance and are co-equally God; the position adopted by the Trinitarians who opposed Arius). Therefore, Alexander allowed the controversy to continue until he ultimately came to believe that it had become dangerous to the peace of the Church. Once he reached this conclusion, he called a local council of bishops and sought their advice. This council decided against Arius and Alexander deposed Arius from his office, excommunicating him and his supporters. Later, Alexander would be criticized for his slow reaction to Arius and the perceived threat posed by his teachings.[15]

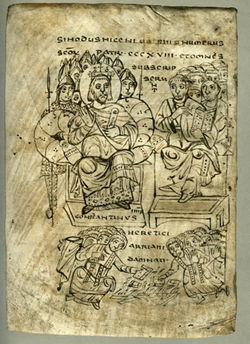

The First Council of Nicaea

But "Arianism" could no longer be contained within the Alexadrian diocese. By the time Bishop Alexander finally acted against his recalcitrant presbyter, Arius's doctrine had spread far beyond his own see; it had become a topic of discussion—and disturbance—for the entire Church. The Church was now a powerful force in the Roman world, with Constantine I having legalized it in 313 through the Edict of Milan. The emperor had taken a personal interest in several ecumenical issues, including the Donatist controversy in 316, and he wanted to bring an end to the Arian dispute. To this end, the emperor sent Hosius, bishop of Córdoba to investigate and, if possible, resolve the controversy. Hosius was armed with an open letter from the Emperor: "Wherefore let each one of you, showing consideration for the other, listen to the impartial exhortation of your fellow-servant." But as the debate continued to rage despite Hosius' efforts, Constantine in AD 325 took an unprecedented step: he called a council to be composed of church prelates from all parts of the empire to resolve this issue, possibly at Hosius' recommendation.[16]

All secular dioceses of the empire sent one or more representatives to the council, save for Roman Britain; the majority of the bishops came from the East. Pope Sylvester I, himself too aged to attend, sent two priests as his delegates. Arius himself attended the council, as did his bishop, Alexander. Also there were Eusebius of Caesarea, Eusebius of Nicomedia and the young deacon Athanasius, who would become the champion of the Trinitarian dogma ultimately adopted by the council and spend most of his life battling Arianism. Before the main conclave convened, Hosius initially met with Alexander and his supporters at Nicomedia.[17] The council would be presided over by the emperor himself, who participated in and even led some of its discussions.[18]

At this First Council of Nicaea twenty-two bishops, led by Eusebius of Nicomedia, came as supporters of Arius. But when some of Arius's writings were read aloud, they are reported to have been denounced as blasphemous by most participants.[19] Those who upheld the notion that Christ was co-eternal and consubstantial with the Father were led by the young archdeacon Athanasius. Those who instead insisted that the Son of God came after God the Father in time and substance, were led by Arius the presbyter. For about two months, the two sides argued and debated,[20] with each appealing to Scripture to justify their respective positions. Arius maintained that the Son of God was a Creature, made from nothing; and that he was God's First Production, before all ages. And he argued that everything else was created through the Son. Thus, said he, only the Son was directly created and begotten of God; furthermore, there was a time that He had no existence. He was capable of His own free will, said Arius, and thus "were He in the truest sense a son, He must have come after the Father, therefore the time obviously was when He was not, and hence He was a finite being."[21] Arius appealed to Scripture, quoting verses such as John 14:28: "the Father is greater than I". And also Colossians 1:15: "Firstborn of all creation." Thus, Arius insisted that the Son was under God the Father, and not co-equal or consubstantial with Him.

According to many accounts, debate at the council became so heated that at one point, Arius was slapped in the face by none other than Nicholas of Myra, who would later be canonized and became better known as "Santa Claus".[22] Under Constantine's influence, the majority of the bishops ultimately agreed upon a creed, known thereafter as the Nicene creed. It included the word homoousios, meaning "consubstantial", or "one in essence", which was incompatible with Arius' beliefs.[23] On June 19, 325, council and emperor issued a circular to the churches in and around Alexandria: Arius and two of his unyielding partisans (Theonas and Secundus)[23] were deposed and exiled to Illyricum, while three other supporters—Theognis of Nicaea, Eusebius of Nicomedia and Maris of Chalcedon—affixed their signatures solely out of deference to the emperor. However, Constantine soon found reason to suspect the sincerity of these three, for he later included them in the sentence pronounced on Arius.

Exile, return and death

The Homoousian party's victory at Nicaea was short-lived, however. Despite Arius's exile and the alleged finality of the Council's decrees, the Arian controversy recommenced at once. When Bishop Alexander died in 327, Athanasius succeeded him, despite not meeting the age requirements for a hierarch. Still committed to pacifying the conflict between Arians and Trinitarians, Constantine gradually became more lenient toward those who the Council of Nicaea had exiled.[24] Though he never repudiated the council or its decrees, the emperor ultimately permitted Arius (who had taken refuge in Palestine) and many of his adherents to return to their homes, once Arius had reformulated his Christology to mute the ideas found most objectionable by his critics. Athanasius was exiled following his condemnation by the First Synod of Tyre in 335 (though he was later recalled), and the Synod of Jerusalem the following year restored Arius to communion. The emperor directed Alexander of Constantinople to receive Arius, despite the bishop's objections; Bishop Alexander responded by earnestly praying that Arius might perish before this could happen.[25] As it turned out—for whatever reason—one day before the Sunday appointed for Arius to be formally readmitted to communion, he suddenly died.[26]

Socrates Scholasticus (a detractor of Arius) described Arius's death as follows:

It was then Saturday, and...going out of the imperial palace, attended by a crowd of Eusebian [Eusebius of Nicomedia is meant here] partisans like guards, he [Arius] paraded proudly through the midst of the city, attracting the notice of all the people. As he approached the place called Constantine's Forum, where the column of porphyry is erected, a terror arising from the remorse of conscience seized Arius, and with the terror a violent relaxation of the bowels: he therefore enquired whether there was a convenient place near, and being directed to the back of Constantine's Forum, he hastened thither. Soon after a faintness came over him, and together with the evacuations his bowels protruded, followed by a copious hemorrhage, and the descent of the smaller intestines: moreover portions of his spleen and liver were brought off in the effusion of blood, so that he almost immediately died. The scene of this catastrophe still is shown at Constantinople, as I have said, behind the shambles in the colonnade: and by persons going by pointing the finger at the place, there is a perpetual remembrance preserved of this extraordinary kind of death.[27]

Many Nicene Christians asserted that Arius's death was miraculous—a consequence of his allegedly heretical views. Several scholarly studies suggest instead that Arius was actually poisoned by his opponents.[28] Even with its namesake's demise, the Arian controversy was far from over, and would not be settled for decades—or centuries, in parts of the West—to come.

Arianism after Arius

Immediate aftermath

Historians report that Constantine, who had never been baptized as a Christian during his lifetime, was baptized on his deathbed by the Arian bishop, Eusebius of Nicodemia.[29]

Constantius II, who succeeded Constantine, was an Arian sympathizer[30] who openly encouraged the Arians by appointing Eusebius of Nicomedia, another sympathizer to Arianism, as Bishop ("Patriarch", in the Eastern Church) of Constantinople. Constantius exiled pro-Nicean prelates, including even Pope Liberius. Divisions appeared within the Arian camp, as Semi-Arians attempted to find a compromise between Arianism and Nicene Trinitarianism. A number of synods were held, and at least fourteen different credal formulations were tried throughout the following years, but none proved successful in resolving the dispute.[31] Athanasius continued his vehement opposition to Arianism, soon to be joined by a trio known to history as the Cappadocian Fathers: SS Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and Gregory of Nyssa. These four men articulated a theological alternative to Arianism that came to be accepted as the definitive orthodox dogma on the subject.

Following the abortive effort by Julian the Apostate to restore paganism in the empire, the emperor Valens—himself an Arian—renewed the persecution of Nicene hierarchs. However, Valen's successor Theodosius I effectively wiped out Arianism once and for all among the elites of the Eastern Empire through a combination of imperial decree, persecution, and the calling of the Second Ecumenical Council in 381, which condemned Arius anew while reaffirming and expanding the Nicene Creed.[32] This generally ended the influence of Arianism among the non-Germanic peoples of the Roman Empire.

Arianism in the West

Things went differently in the Western Empire. During the reign of Constantius II, the Arian Gothic convert Ulfilas was consecrated a bishop by Eusebius of Nicomedia and sent to missionize his people. His success ensured the survival of Arianism among the Goths and Vandals until the beginning of the eighth century, when these kingdoms succumbed to their Nicean neighbors or accepted Nicean Christianity. Arians also continued to exist in North Africa, Spain and portions of Italy, until finally suppressed during the sixth and seventh centuries.[33]

During the Protestant Reformation, a Polish sect known as the Polish Brethren were often referred to as Arians, due to their rejection of the Trinity.[34]

Arianism today

A modern English church called the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church claims to follow Arian teachings, canonizing Arius on June 16, 2006.[35] However, they do not accept the Virgin Birth and bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ,[36] which places them in opposition to Arius himself, who accepted both. Furthermore, their "Arian Catholic Creed"[36] is a modern creation, not an ancient statement of faith.

Members of the congregation of Jehovah's Witnesses are sometimes referred to as "modern-day Arians", usually by their opponents.[37] However, the Witnesses differ from Arians by saying that the Son can fully know the Father (something Arius himself denied), and by their denial of literal personality to the Holy Spirit (Arius considered the Holy Spirit to be a person or a high angel, whereas the Witnesses consider the Holy Spirit to be God's divine breath or active force). Arians generally worshipped and prayed to Jesus as God, while the Witnesses, though they do reverence Jesus as God's Son and Messiah, do not give Him the same kind of worship as they give to God the Father.[38]

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the "Mormons") are sometimes accused of being Arians by their detractors.[39] However, the Christology of the LDS religion differs in several significant aspects from Arian theology.[40]

Arius's doctrine

Introduction

In explaining his actions against Arius, Alexander of Alexandria wrote a letter to Alexander of Constantinople and Eusebius of Nicomedia (where the emperor was then residing), detailing the errors into which he believed Arius had fallen. According to Alexander, Arius taught:

That God was not always the Father, but that there was a period when he was not the Father; that the Word of God was not from eternity, but was made out of nothing; for that the ever-existing God (‘the I AM’—the eternal One) made him who did not previously exist, out of nothing; wherefore there was a time when he did not exist, inasmuch as the Son is a creature and a work. That he is neither like the Father as it regards his essence, nor is by nature either the Father’s true Word, or true Wisdom, but indeed one of his works and creatures, being erroneously called Word and Wisdom, since he was himself made of God’s own Word and the Wisdom which is in God, whereby God both made all things and him also. Wherefore he is as to his nature mutable and susceptible of change, as all other rational creatures are: hence the Word is alien to and other than the essence of God; and the Father is inexplicable by the Son, and invisible to him, for neither does the Word perfectly and accurately know the Father, neither can he distinctly see him. The Son knows not the nature of his own essence: for he was made on our account, in order that God might create us by him, as by an instrument; nor would he ever have existed, unless God had wished to create us.[41]

Alexander also refers to Arius's poetical Thalia:

God has not always been Father; there was a moment when he was alone, and was not yet Father: later he became so. The Son is not from eternity; he came from nothing.[42]

The Logos

This question of the exact relationship between the Father and the Son (a part of the theological science of Christology) had been raised some fifty years before Arius, when Paul of Samosata was deposed in 269 for agreeing with those who used the word homoousios (Greek for same substance) to express the relation between the Father and the Son. This term was thought at that time to have a Sabellian tendency, though—as events showed—this was on account of its scope not having been satisfactorily defined.[43] In the discussion which followed Paul's deposition, Dionysius, the Bishop of Alexandria, used much the same language as Arius did later, and correspondence survives in which Pope Dionysius blames him for using such terminology. Dionysius responded with an explanation widely interpreted as vacillating. The Synod of Antioch, which condemned Paul of Samosata, had expressed its disapproval of the word homoousios in one sense, while Bishop Alexander undertook its defense in another. Although the controversy seemed to be leaning toward the opinions later championed by Arius, no firm decision had been made on the subject; in an atmosphere so intellectual as that of Alexandria, the debate seemed bound to resurface—and even intensify—at some point in the future.

Arius endorsed the following doctrines about The Son or The Word (Logos, referring to Jesus; see the Gospel of John 1:1):

- that the Word (Logos) and the Father were not of the same essence (ousia);

- that the Son was a created being (ktisma or poiema); and

- that the worlds were created through him, so he must have existed before them and before all time.

- However, there was a "once" [Arius did not use words meaning "time", such as chronos or aion] when He did not exist, before he was begotten of the Father.

The Thalia

According to Athanasius, Arius authored a poem called the Thalia ("abundance", "good cheer" or "banquet"): a summary of his views on the Logos.[44] Part of this Thalia is quoted in Athanasius's Four Discourses Against the Arians:

- "And so God Himself, as he really is, is inexpressible to all.

- He alone has no equal, no one similar ('homoios'), and no one of the same glory.

- We call Him unbegotten, in contrast to him who by nature is begotten.

- We praise Him as without beginning, in contrast to him who has a beginning.

- We worship Him as timeless, in contrast to him who in time has come to exist.

- He who is without beginning made the Son a beginning of created things. He produced him as a son for Himself, by begetting him.

- He [the Son] has none of the distinct characteristics of God's own being ('kat' hypostasis')

- For he is not equal to, nor is he of the same being ('homoousios') as Him."

Also from the Thalia:

- "At God’s will the Son has the greatness and qualities that he has.

- His existence from when and from whom and from then—are all from God.

- He, though strong God, praises in part ('ek merous') his superior".

Thus, said Arius, God's first thought was the creation of Jesus Christ, therefore time started with the creation of the Logos or Word in Heaven.

In this portion of the Thalia, Arius endeavors to explain the ultimate incomprehensibility of the Father to the Son:

- "In brief, God is inexpressible to the Son.

- For He is in himself what He is, that is, indescribable,

- So that the Son does not comprehend any of these things or have the understanding to explain them.

- For it is impossible for him to fathom the Father, who is by Himself.

- For the Son himself does not even know his own essence ('ousia').

- For being Son, his existence is most certainly at the will of the Father.

- What reasoning allows, that he who is from the Father should comprehend and know his own parent?

- For clearly that which has a beginning is not able to conceive of or grasp the existence of that which has no beginning".

Here, Arius explains how the Son could still be God, even if he did not exist eternally:

- "Understand that the Monad [eternally] was; but the Dyad was not before it came into existence.

- It immediately follows that, although the Son did not exist, the Father was still God.

- Hence the Son, not being [eternal] came into existence by the Father’s will,

- He [the Son] is the Only-begotten God, and this one is alien from [all] others."

Extant writings

Three surviving letters attributed to Arius are his letter to Alexander of Alexandria,[45] his letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia,[46] and his confession to Constantine.[47] In addition, several letters addressed by others to Arius survive, together with brief quotations contained within the polemical works of his opponents. These quotations are often short and taken out of context, and it is difficult to tell how accurately they quote him or represent his true thinking.

Arius' Thalia (literally, "Festivity"), a popularized work combining prose and verse, survives in quoted fragmentary form. The two available references from this work are recorded by his opponent Athanasius: the first is a report of Arius's teaching in Orations Against the Arians, 1:5-6. This paraphrase has negative comments interspersed throughout, so it is difficult to consider it as being completely reliable.[48] The second quotation is found in the document On the Councils of Arminum and Seleucia, pg. 15. This passage is entirely in irregular verse, and seems to be a direct quotation or a compilation of quotations;[49] it may have been written by someone other than Athanasius, perhaps even a person sympathetic to Arius.[50] This second quotation does not contain several statements usually attributed to Arius by his opponents, is in metrical form, and resembles other passages that have been attributed to Arius. It also contains some positive statements about the Son.[51] But although these quotations seem reasonably accurate, their proper context is lost, thus their place in Arius' larger system of thought is impossible to reconstruct.[52]

See also

- Anomoeanism

- Nontrinitarianism

- Arianism

- Semi-Arianism

- Unitarianism

- First Council of Nicaea

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rowan Williams, Arius: Heresy and Tradition - Revised Edition, 1987, 2001 - Synopsis

- ↑ New Advent Encyclopedia - Theodosius I,[1]

- ↑ 2. R.C.P. Hanson, The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God, (Edinburgh: 1988), 127 28. M.R. Kopeck, "Neo Arian Religion: Evidence of the Apostolic Constitutions", from Arianism: Historical and Theological Reassessments, (Philadelphia: 1985) 160-2.

- ↑ Urkunde 33 = Athanasius, Defense of the Nicene Definition 39; Socrates, Church History 1.9.30; Gelasius, Church History 2.36.1.

- ↑ James T. Dennison, Jr. The Rehabilitation of Arius and the Denigration of Athanasius, Northwest Theological Seminary, Lynnwood, WA. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Michael O'Carroll, Trinitas (Delaware: Michael Glazier, Inc, 1987) p. 23.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 2, p. 297. Danbury, CT:Grolier Incorporated, 1997. ISBN 0-7172-0129-5.

- ↑ Carroll, A History of Christendom, II, p. 10

- ↑ Rowan Williams, Arius: Heresy and Tradition - Revised Edition, 1987, 2001 - p. 235

- ↑ Socrates of Constantinople, Church History, book 1, chapter 5.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Vasiliev, A. Arianism and the Council of Nicaea, from History of the Byzantine Empire, Chapter One. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ "Origen of Alexandria [The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]". Iep.utm.edu. 2005-05-02. http://www.iep.utm.edu/origen-of-alexandria/. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ↑ De Principiis</cit> I:2:2 (from The Ante-Nicene Fathers vol. IV): "Wherefore we have always held that God is the Father of His only-begotten Son . . . but without any beginning."

- ↑ St. Arius's Concept of Christ, from the Arian Catholic Church Website. Retrieved on 2010-02-02. Origen was later condemned as a heretic by the Fifth Ecumenical Council of the Church.

- ↑ "Arius of Alexandria, Priest and Martyr:" Retrieved on 11/29/2009

- ↑ Carroll, 11

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 1, chapter 7.

- ↑ A. Vasiliev, Arianism and the Council of Nicaea, from History of the Byzantine Empire, Chapter One. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Carroll, p. 11.

- ↑ "Babylon the Great Has Fallen" - God's Kingdom Rules! - Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc., 1963, pg 477

- ↑ M'Clintock and Strong's Cyclopedia, Volume 7, page 45a.

- ↑ Bishop Nicholas Loses His Cool at the Council of Nicea. From the St. Nicholas center. See also St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, from the website of the Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Carroll, p. 12.

- ↑ A. Vasiliev, Arianism and the Council of Nicaea. From History of the Byzantine Empire, Chapter One. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ John William Drapier, History of the Intellectual Development of Europe, Ch. IX, pp. 358-59. Quoted in The Formulation of the Trinity, Section: "The Events Following the Council of Nicea". Retrieved on 2010-02-08.

- ↑ Socratese and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories, Chapter XXIX, pp,1-2. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ A Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., with an Account of the Principal Sects and Heresies by Henry Wace.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 21, (1776–88), Jonathan Kirsch, God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism, 2004, and Charles Freeman, The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason, 2002.

- ↑ D.S. Scrum, Arius, section "Arian Reaction - Athanasius". See also Vasiliev, A. Arianism and the Council of Nicaea, from History of the Byzantine Empire, Chapter One. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Jones, A.H.M, The Later Roman Empire, 284-602: a Social, Economic and Administrative Survey (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1986), p. 118.

- ↑ Msgr. Cantley, From Nicea to First Constantinople, pp. 1-2. Retrieved on 2010-02-03.

- ↑ See Vasiliev, A., The Church and the State at the End of the Fourth Century, from History of the Byzantine Empire, Chapter One. Retrieved on 2010-02-02. The text of this version of the Nicene creed is available at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf214.ix.iii.html.

- ↑ Arianism, from The Columbia Encyclopedia. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Earl Morse Wilbur, The Socinian Exiles in East Prussia, from A History of Unitarianism in Transylvania, England and America, Chapter XXXIX. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ See "The Canonization of Arius", on the Arian Catholic website.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 See "The Virgin Birth: Separating Myth From Fact" and "The Resurrection", on the Arian Catholic website.

- ↑ See Modern Day Arians, Jehovah's Witnesses are Modern-Day Arians and Jehovah's Witnesses, among other similar sources.

- ↑ Watchtower 1984 9/1 p. 25-30; "Should you believe in the Trinity?" http://www.watchtower.org/e/ti/index.htm

- ↑ See, for instance, the article entitled Mormons in Daniel S. Tuttle, A Religious Encyclopedia, New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1891 - 3rd ed., pg. 1578. See Are Mormons Arians? and Response for modern Mormon attempts to answer these charges. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Are Mormons Arians?. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories, Chapter VI. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Carroll, History of Christendom, II, p. 10

- ↑ See the Catholic Encyclopedia, article Paul of Samosata. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ↑ Wisconsin Lutheran College:Arius-Thalia. Retrieved on 2010-01-29.

- ↑ Preserved by Athanasius, On the Councils of Arminum and Seleucia, 16; Epiphanius, Refutation of All Heresies, 69.7; and Hilary, On the Trinity, 4.12)

- ↑ Recorded by Epiphanius, Refutation of All Heresies, 69.6 and Theodoret, Church History, 1.5

- ↑ Recorded in Socrates Scholasticus, Church History 1.26.2 and Sozomen, Church History 2.27.6-10

- ↑ Williams, Arius, p. 99.

- ↑ Williams, Arius, pp. 98-9.

- ↑ Hanson, The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God, pp. 10-15, esp. pg. 12.

- ↑ Stevenson, A New Eusebius: Documents Illustrating the History of the Church to AD 337, pp. 330-32.

- ↑ Williams, Arius, p. 95.

Bibliography

- Athanasius of Alexandria. History of the Arians. Online at CCEL. Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Part VI Part VII Part VIII. Accessed 13 December 2009.

- Ayres, Lewis. Nicaea and its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Hanson, R.P.C. The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy, 318–381. T&T Clark, 1988.

- Parvis, Sara. Marcellus of Ancyra And the Lost Years of the Arian Controversy 325–345. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Rusch, William C. The Trinitarian Controversy. Sources of Early Christian Thought, 1980. ISBN 0-8006-1410-0

- Schaff, Philip. "Theological Controversies and the Development of Orthodoxy". In History of the Christian Church, Vol III, Ch. IX. Online at CCEL. Accessed 13 December 2009.

- Wace, Henry. A Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., with an Account of the Principal Sects a.d Heresies]. Online at CCEL. Accessed 13 December 2009.

- Williams, Rowan. Arius: Heresy and Tradition. Revised edition, 2001. ISBN 0-8028-4969-5

External links

- OrthodoxWiki Article critical of Arius, written from an Eastern Orthodox viewpoint

- Athanasius' Discourse against the Arians Taken from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Catholic Encyclopedia Article critical of Arius, written from a Roman Catholic viewpoint

- The Complete Extant Works of Arius From the Wisconsin Lutheran College website page entitled "Fourth Century Christianity."

- Holy Arian Catholic and Apostolic Church Church claiming to be founded on Arian doctrines, though differing with classical Arianism on some topics, including the Virgin Birth and resurrection.

- Life of St. Arius Arius' life, from the viewpoint of the Holy Arian Catholic and Apostolic Church, which canonized him in 2006.

- Eusebius's Letter regarding the Council of Nicaea Taken from the Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Constantine's Letter to Alexander and Arius By Socrates Scolasticus (an opponent of Arius). Taken from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library.