Apple

| Apple | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A typical apple | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Subfamily: | Maloideae or Spiraeoideae [1] |

| Tribe: | Maleae |

| Genus: | Malus |

| Species: | M. domestica |

| Binomial name | |

| Malus domestica Borkh. |

|

The apple is the pomaceous fruit of the apple tree, species Malus domestica in the rose family (Rosaceae) and is a perennial. It is one of the most widely cultivated tree fruits, and the most widely known of the many members of genus Malus that are used by humans.

The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor is still found today. There are more than 7,500 known cultivars of apples, resulting in a range of desired characteristics. Cultivars vary in their yield and the ultimate size of the tree, even when grown on the same rootstock.[2]

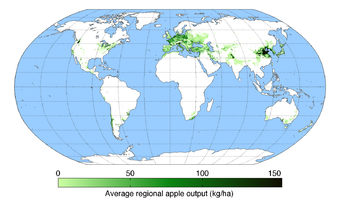

At least 55 million tons of apples were grown worldwide in 2005, with a value of about $10 billion. China produced about 35% of this total.[3] The United States is the second-leading producer, with more than 7.5% of world production. Iran is third, followed by Turkey, Russia, Italy and India.

Contents |

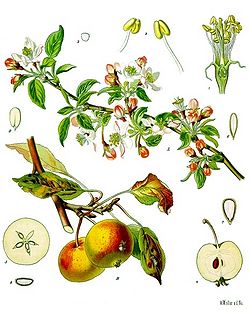

Botanical information

The apple forms a tree that is small and deciduous, reaching 3 to 12 metres (9.8 to 39 ft) tall, with a broad, often densely twiggy crown.[4] The leaves are alternately arranged simple ovals 5 to 12 cm long and 3–6 centimetres (1.2–2.4 in) broad on a 2 to 5 centimetres (0.79 to 2.0 in) petiole with an acute tip, serrated margin and a slightly downy underside. Blossoms are produced in spring simultaneously with the budding of the leaves. The flowers are white with a pink tinge that gradually fades, five petaled, and 2.5 to 3.5 centimetres (0.98 to 1.4 in) in diameter. The fruit matures in autumn, and is typically 5 to 9 centimetres (2.0 to 3.5 in) diameter. The center of the fruit contains five carpels arranged in a five-point star, each carpel containing one to three seeds.[4]

Wild ancestors

The wild ancestors of Malus domestica are Malus sieversii, found growing wild in the mountains of Central Asia in southern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Xinjiang, China,[5] and possibly also Malus sylvestris.[6]

History

The center of diversity of the genus Malus is in eastern Turkey. The apple tree was perhaps the earliest tree to be cultivated,[7] and its fruits have been improved through selection over thousands of years. Alexander the Great is credited with finding dwarfed apples in Asia Minor in 300 BCE;[4] those he brought back to Macedonia might have been the progenitors of dwarfing root stocks. Winter apples, picked in late autumn and stored just above freezing, have been an important food in Asia and Europe for millennia, as well as in Argentina and in the United States since the arrival of Europeans.[7] Apples were brought to North America with colonists in the 1600s,[4] and the first apple orchard on the North American continent was said to be near Boston in 1625. In the 1900s, irrigation projects in Washington state began and allowed the development of the multibillion dollar fruit industry, of which the apple is the leading species.[4]

Cultural aspects

Germanic paganism

In Norse mythology, the goddess Iðunn is portrayed in the Prose Edda (written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson) as providing apples to the gods that give them eternal youthfulness. English scholar H. R. Ellis Davidson links apples to religious practices in Germanic paganism, from which Norse paganism developed. She points out that buckets of apples were found in the Oseberg ship burial site in Norway, and that fruit and nuts (Iðunn having been described as being transformed into a nut in Skáldskaparmál) have been found in the early graves of the Germanic peoples in England and elsewhere on the continent of Europe, which may have had a symbolic meaning, and that nuts are still a recognized symbol of fertility in southwest England.[8]

Davidson notes a connection between apples and the Vanir, a tribe of gods associated with fertility in Norse mythology, citing an instance of eleven "golden apples" being given to woo the beautiful Gerðr by Skírnir, who was acting as messenger for the major Vanir god Freyr in stanzas 19 and 20 of Skírnismál. Davidson also notes a further connection between fertility and apples in Norse mythology in chapter 2 of the Völsunga saga when the major goddess Frigg sends King Rerir an apple after he prays to Odin for a child, Frigg's messenger (in the guise of a crow) drops the apple in his lap as he sits atop a mound.[9] Rerir's wife's consumption of the apple results in a six-year pregnancy and the Caesarean section birth of their son - the hero Völsung.[10]

Further, Davidson points out the "strange" phrase "Apples of Hel" used in an 11th-century poem by the skald Thorbiorn Brúnarson. She states this may imply that the apple was thought of by the skald as the food of the dead. Further, Davidson notes that the potentially Germanic goddess Nehalennia is sometimes depicted with apples and that parallels exist in early Irish stories. Davidson asserts that while cultivation of the apple in Northern Europe extends back to at least the time of the Roman Empire and came to Europe from the Near East, the native varieties of apple trees growing in Northern Europe are small and bitter. Davidson concludes that in the figure of Iðunn "we must have a dim reflection of an old symbol: that of the guardian goddess of the life-giving fruit of the other world."[8]

Greek mythology

Apples appear in many religious traditions, often as a mystical or forbidden fruit. One of the problems identifying apples in religion, mythology and folktales is that the word "apple" was used as a generic term for all (foreign) fruit, other than berries, but including nuts, as late as the 17th century.[11] For instance, in Greek mythology, the Greek hero Heracles, as a part of his Twelve Labours, was required to travel to the Garden of the Hesperides and pick the golden apples off the Tree of Life growing at its center.[12][13][14]

The Greek goddess of discord, Eris, became disgruntled after she was excluded from the wedding of Peleus and Thetis.[15] In retaliation, she tossed a golden apple inscribed Καλλίστη (Kalliste, sometimes transliterated Kallisti, 'For the most beautiful one'), into the wedding party. Three goddesses claimed the apple: Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Paris of Troy was appointed to select the recipient. After being bribed by both Hera and Athena, Aphrodite tempted him with the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta. He awarded the apple to Aphrodite, thus indirectly causing the Trojan War.

Atalanta, also of Greek mythology, raced all her suitors in an attempt to avoid marriage. She outran all but Hippomenes (a.k.a. Melanion, a name possibly derived from melon the Greek word for both "apple" and fruit in general),[13] who defeated her by cunning, not speed. Hippomenes knew that he could not win in a fair race, so he used three golden apples (gifts of Aphrodite, the goddess of love) to distract Atalanta. It took all three apples and all of his speed, but Hippomenes was finally successful, winning the race and Atalanta's hand.[12]

Bibliography

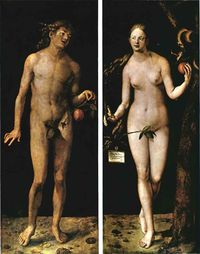

Though the forbidden fruit in the Book of Genesis is not identified, popular Christian tradition has held that it was an apple that Eve coaxed Adam to share with her.[16] This may have been the result of Renaissance painters adding elements of Greek mythology into biblical scenes (alternative interpretations also based on Greek mythology occasionally replace the apple with a pomegranate). In this case the unnamed fruit of Eden became an apple under the influence of story of the golden apples in the Garden of Hesperides. As a result, in the story of Adam and Eve, the apple became a symbol for knowledge, immortality, temptation, the fall of man into sin, and sin itself. In Latin, the words for "apple" and for "evil" are similar in the singular (malus—apple, malum—evil) and identical in the plural (mala). This may also have influenced the apple becoming interpreted as the biblical "forbidden fruit". The larynx in the human throat has been called Adam's apple because of a notion that it was caused by the forbidden fruit sticking in the throat of Adam.[16] The apple as symbol of sexual seduction has been used to imply sexuality between men, possibly in an ironic vein.[16]

Apple cultivars

There are more than 7,500 known cultivars of apples.[17] Different cultivars are available for temperate and subtropical climates. One large collection of over 2,100 [18] apple cultivars is housed at the National Fruit Collection in England. Most of these cultivars are bred for eating fresh (dessert apples), though some are cultivated specifically for cooking (cooking apples) or producing cider. Cider apples are typically too tart and astringent to eat fresh, but they give the beverage a rich flavour that dessert apples cannot.[19]

Commercially popular apple cultivars are soft but crisp. Other desired qualities in modern commercial apple breeding are a colourful skin, absence of russeting, ease of shipping, lengthy storage ability, high yields, disease resistance, typical 'Red Delicious' apple shape, and popular flavour.[2] Modern apples are generally sweeter than older cultivars, as popular tastes in apples have varied over time. Most North Americans and Europeans favour sweet, subacid apples, but tart apples have a strong minority following.[20] Extremely sweet apples with barely any acid flavour are popular in Asia[20] and especially India.[19]

Old cultivars are often oddly shaped, russeted, and have a variety of textures and colours. Some find them to have a better flavour than modern cultivators,[21] but may have other problems which make them commercially unviable, such as low yield, liability to disease, or poor tolerance for storage or transport. A few old cultivars are still produced on a large scale, but many have been kept alive by home gardeners and farmers that sell directly to local markets. Many unusual and locally important cultivars with their own unique taste and appearance exist; apple conservation campaigns have sprung up around the world to preserve such local cultivars from extinction. In the United Kingdom, old cultivars such as 'Cox's Orange Pippin' and 'Egremont Russet' are still commercially important even though by modern standards they are low yielding and disease prone.[4]

Apple production

Apple breeding

In the wild, apples grow quite readily from seeds. However, like most perennial fruits, apples are ordinarily propagated asexually by grafting. This is because seedling apples are an example of "extreme heterozygotes", in that rather than inheriting DNA from their parents to create a new apple with those characteristics, they are instead different from their parents, sometimes radically.[22] Triploids have an additional reproductive barrier in that the 3 sets of chromosomes cannot be divided evenly during meiosis, yielding unequal segregation of the chromosomes (aneuploids). Even in the very unusual case when a triploid plant can produce a seed (apples are an example), it happens infrequently, and seedlings rarely survive.[23] Most new apple cultivars originate as seedlings, which either arise by chance or are bred by deliberately crossing cultivars with promising characteristics.[24] The words 'seedling', 'pippin', and 'kernel' in the name of an apple cultivar suggest that it originated as a seedling. Apples can also form bud sports (mutations on a single branch). Some bud sports turn out to be improved strains of the parent cultivar. Some differ sufficiently from the parent tree to be considered new cultivars.[25]

Breeders can produce more rigid apples through crossing.[26] For example, the Excelsior Experiment Station of the University of Minnesota has, since the 1930s, introduced a steady progression of important hardy apples that are widely grown, both commercially and by backyard orchardists, throughout Minnesota and Wisconsin. Its most important introductions have included 'Haralson' (which is the most widely cultivated apple in Minnesota), 'Wealthy', 'Honeygold', and 'Honeycrisp'.

Apples have been acclimatized in Ecuador at very high altitudes, where they provide crops twice per year because of constant temperate conditions in a whole year.[27]

Apple rootstocks

Rootstocks used to control tree size have been used in apple cultivation for over 2,000 years. Dwarfing rootstocks were probably discovered by chance in Asia. Alexander the Great sent samples of dwarf apple trees back to his teacher, Aristotle, in Greece. They were maintained at the Lyceum, a center of learning in Greece.

Most modern apple rootstocks were bred in the 20th century. Much research into the existing rootstocks was begun at the East Malling Research Station in Kent, England. Following that research, Malling worked with the John Innes Institute and Long Ashton to produce a series of different rootstocks with disease resistance and a range of different sizes, which have been used all over the world.

Pollination

Apples are self-incompatible; they must cross-pollinate to develop fruit. During the flowering each season, apple growers usually provide pollinators to carry the pollen. Honeybees are most commonly used. Orchard mason bees are also used as supplemental pollinators in commercial orchards. Bumble bee queens are sometimes present in orchards, but not usually in enough quantity to be significant pollinators.[25]

There are four to seven pollination groups in apples, depending on climate:

- Group A – Early flowering, May 1 to 3 in England (Gravenstein, Red Astrachan)

- Group B – May 4 to 7 (Idared, McIntosh)

- Group C – Mid-season flowering, May 8 to 11 (Granny Smith, Cox's Orange Pippin)

- Group D – Mid/late season flowering, May 12 to 15 (Golden Delicious, Calville blanc d'hiver)

- Group E – Late flowering, May 16 to 18 (Braeburn, Reinette d'Orléans)

- Group F – May 19 to 23 (Suntan)

- Group H – May 24 to 28 (Court-Pendu Gris) (also called Court-Pendu plat)

One cultivar can be pollinated by a compatible cultivar from the same group or close (A with A, or A with B, but not A with C or D).[28]

Varieties are sometimes classed as to the day of peak bloom in the average 30 day blossom period, with pollinizers selected from varieties within a 6 day overlap period.

Maturation and harvest

Cultivars vary in their yield and the ultimate size of the tree, even when grown on the same rootstock. Some cultivars, if left unpruned, will grow very large, which allows them to bear much more fruit, but makes harvesting very difficult. Mature trees typically bear 40–200 kilograms (88–440 lb) of apples each year, though productivity can be close to zero in poor years. Apples are harvested using three-point ladders that are designed to fit amongst the branches. Dwarf trees will bear about 10–80 kilograms (22–180 lb) of fruit per year.[25]

Storage

Commercially, apples can be stored for some months in controlled-atmosphere chambers to delay ethylene-induced onset of ripening. The apples are commonly stored in chambers with higher concentrations of carbon dioxide with high air filtration. This prevents ethylene concentrations from rising to higher amounts and preventing ripening from moving too quickly. Ripening continues when the fruit is removed.[29] For home storage, most varieties of apple can be held for approximately two weeks when kept at the coolest part of the refrigerator (i.e. below 5°C). Some types, including the Granny Smith and Fuji, have a longer shelf life.[30]

Pests and diseases

The trees are susceptible to a number of fungal and bacterial diseases and insect pests. Many commercial orchards pursue an aggressive program of chemical sprays to maintain high fruit quality, tree health, and high yields. A trend in orchard management is the use of organic methods. These use a less aggressive and direct methods of conventional farming. Instead of spraying potent chemicals, often shown to be potentially dangerous and maleficent to the tree in the long run, organic methods include encouraging or discouraging certain cycles and pests. To control a specific pest, organic growers might encourage the prosperity of its natural predator instead of outright killing it, and with it the natural biochemistry around the tree. Organic apples generally have the same or greater taste than conventionally grown apples, with reduced cosmetic appearances.[31]

A wide range of pests and diseases can affect the plant; three of the more common diseases/pests are mildew, aphids and apple scab.

- Mildew: which is characterized by light grey powdery patches appearing on the leaves, shoots and flowers, normally in spring. The flowers will turn a creamy yellow colour and will not develop correctly. This can be treated in a manner not dissimilar from treating Botrytis; eliminating the conditions which caused the disease in the first place and burning the infected plants are among the recommended actions to take.[32][32]

- Aphids: There are five species of aphids commonly found on apples: apple grain aphid, rosy apple aphid, apple aphid, spirea aphid and the woolly apple aphid. The aphid species can be identified by their colour, the time of year when they are present and by differences in the cornicles, which are small paired projections from the rear of aphids.[32] Aphids feed on foliage using needle-like mouth parts to suck out plant juices. When present in high numbers, certain species reduce tree growth and vigor.[33]

- Apple scab: Symptoms of scab are olive-green or brown blotches on the leaves.[34] The blotches turn more brown as time progresses, then brown scabs form on the fruit.[32] The diseased leaves will fall early and the fruit will become increasingly covered in scabs - eventually the fruit skin will crack. Although there are chemicals to treat scab, their use might not be encouraged as they are quite often systematic, which means they are absorbed by the tree, and spread throughout the fruit.[34]

Among the most serious disease problems are fireblight, a bacterial disease; and Gymnosporangium rust, and black spot, two fungal diseases.[33]

Young apple trees are also prone to mammal pests like mice and deer, which feed on the soft bark of the trees, especially in winter.

Records

Guinness World Records reports that the heaviest apple known weighed 1.849 kg (4 lb 1 oz) and was grown in Hirosaki city, Japan in 2005.[35]

Commerce

At least 55 million tonnes of apples were grown worldwide in 2005, with a value of about $10 billion. China produced about two-fifths of this total.[36] United States is the second leading producer, with more than 7.5% of the world production.[24]

In the United States, more than 60% of all the apples sold commercially are grown in Washington state.[37] Imported apples from New Zealand and other more temperate areas are competing with US production and increasing each year.[36]

Most of Australia's apple production is for domestic consumption. Imports from New Zealand have been disallowed under quarantine regulations for fireblight since 1921.[38]

The largest exporters of apples in 2006 were China, Chile, Italy, France and the U.S., while the biggest importers in the same year were Russia, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands.[39]

| Top Ten Apple Producers — 11 June 2008 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (Tonnes) | Footnote | ||

| 27 507 000 | F | |||

| 4 237 730 | ||||

| 2 660 000 | F | |||

| 2 266 437 | ||||

| 2 211 000 | F | |||

| 2 072 500 | ||||

| 2 001 400 | ||||

| 1 800 000 | F | |||

| 1 390 000 | F | |||

| 1 300 000 | F | |||

| World | 64 255 520 | A | ||

| No symbol = official figure, F = FAO estimate, A = Aggregate (may include official, semi-official, or estimates); Source: FAO |

||||

Human consumption

Apples can be canned or juiced. They are milled to produce apple cider (non-alcoholic, sweet cider) and filtered for apple juice. The juice can be fermented to make cider (alcoholic, hard cider), ciderkin, and vinegar. Through distillation, various alcoholic beverages can be produced, such as applejack, Calvados,[40] and apple wine. Pectin and apple seed oil may also produced.

Apples are an important ingredient in many desserts, such as apple pie, apple crumble, apple crisp and apple cake. They are often eaten baked or stewed, and they can also be dried and eaten or reconstituted (soaked in water, alcohol or some other liquid) for later use. Puréed apples are generally known as apple sauce. Apples are also made into apple butter and apple jelly. They are also used (cooked) in meat dishes.

- In the UK, a toffee apple is a traditional confection made by coating an apple in hot toffee and allowing it to cool. Similar treats in the US are candy apples (coated in a hard shell of crystallised sugar syrup), and caramel apples, coated with cooled caramel.

- Apples are eaten with honey at the Jewish New Year of Rosh Hashanah to symbolize a sweet new year.[40]

- Farms with apple orchards may open them to the public, so consumers may themselves pick the apples they will buy.[40]

Sliced apples turn brown with exposure to air due to the conversion of natural phenolic substances into melanin upon exposure to oxygen.[41] Different cultivars vary in their propensity to brown after slicing. Sliced fruit can be treated with acidulated water to prevent this effect.[41]

Organic apples are commonly produced in the United States.[42] Organic production is difficult in Europe, though a few orchards have done so with commercial success,[42] using disease-resistant cultivars and the very best cultural controls. The latest tool in the organic repertoire is a spray of a light coating of kaolin clay, which forms a physical barrier to some pests, and also helps prevent apple sun scald.[25][42]

Fallen apples

Eating fallen apples (known in the UK as 'windfalls'), rather than picking directly from the tree, is generally safe. There may be a risk of food poisoning if the orchard is also the area of keeping cattle or other animals, which may contaminate the apples with feces. Still, the risk may be significantly higher if the apples are used to make home-made (unpasteurized) cider or juice, thus letting E. coli multiply.[43]

On the other hand, if the apples are eaten unprocessed, and kept free from risk of contamination with animal feces, then eating fallen apples is generally safe, even if there is some general decay or worms in them. Still, they may be submerged in water with salt added, which kills the worms.[44] Apparent molds may be largely removed by putting in water with some vinegar added,[44] but if they are of a large quantity, then there might be mold or mold products left to evoke mold health issues such as allergic reactions and respiratory problems.

Apple allergy

Oral allergy syndrome is an allergic reaction some people will experience due to the birch pollen left on the apples.[45][46] Because the pollen is the main irritant, only the raw apples, especially their skin, cause the allergic reaction. Cooked apples do not cause these symptoms as the heat denatures the proteins in the pollen, rendering them harmless to those sensitive. If one is allergic to apples, he or she may also experience an allergic reaction with other fruits in the Rosaceae family which include peaches and hazelnuts.[45]

Symptoms

Symptoms vary from person to person but are generally mild. This typically includes the sensation of itching and swelling around the mouth and lips. Other symptoms include watery eyes, runny nose and sneezing. Hives may develop in those who have a high sensitivity to the pollen. Abdominal pain and diarrhea may also occur.[45]

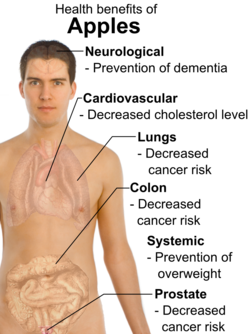

Health benefits

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 218 kJ (52 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 13.81 g |

| Sugars | 10.39 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2.4 g |

| Fat | 0.17 g |

| Protein | 0.26 g |

| Water | 85.56 g |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 3 μg (0%) |

| Thiamine (Vit. B1) | 0.017 mg (1%) |

| Riboflavin (Vit. B2) | 0.026 mg (2%) |

| Niacin (Vit. B3) | 0.091 mg (1%) |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 0.061 mg (1%) |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.041 mg (3%) |

| Folate (Vit. B9) | 3 μg (1%) |

| Vitamin C | 4.6 mg (8%) |

| Calcium | 6 mg (1%) |

| Iron | 0.12 mg (1%) |

| Magnesium | 5 mg (1%) |

| Phosphorus | 11 mg (2%) |

| Potassium | 107 mg (2%) |

| Zinc | 0.04 mg (0%) |

| Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient database |

|

The proverb "An apple a day keeps the doctor away.", addressing the health effects of the fruit, dates from 19th century Wales.[51] Research suggests that apples may reduce the risk of colon cancer, prostate cancer and lung cancer.[47] Compared to many other fruits and vegetables, apples contain relatively low amounts of vitamin C, but are a rich source of other antioxidant compounds.[41] The fiber content, while less than in most other fruits, helps regulate bowel movements and may thus reduce the risk of colon cancer. They may also help with heart disease,[52] weight loss,[52] and controlling cholesterol,[52] as they do not have any cholesterol, have fiber, which reduces cholesterol by preventing reabsorption, and are bulky for their caloric content, like most fruits and vegetables.[49][52]

There is evidence that in vitro apples possess phenolic compounds which may be cancer-protective and demonstrate antioxidant activity.[53] The predominant phenolic phytochemicals in apples are quercetin, epicatechin, and procyanidin B2.[54]

Apple juice concentrate has been found to increase the production of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in mice, providing a potential mechanism for the "prevention of the decline in cognitive performance that accompanies dietary and genetic deficiencies and aging." Other studies have shown an "alleviat[ion of] oxidative damage and cognitive decline" in mice after the administration of apple juice.[50]

The seeds are mildly poisonous, containing a small amount of amygdalin, a cyanogenic glycoside; it usually is not enough to be dangerous to humans, but it can deter birds.[55]

References

- ↑ Potter, D.; Eriksson, T.; Evans, R.C.; Oh, S.H.; Smedmark, J.E.E.; Morgan, D.R.; Kerr, M.; Robertson, K.R.; Arsenault, M.P.; Dickinson, T.A.; Campbell, C.S. (2007). Phylogeny and classification of Rosaceae. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 266(1–2): 5–43.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Apple - Malus domestica". Natural England. http://www.plantpress.com/wildlife/o523-apple.php. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ "Apple". Jinxiang High Garlics Co., Ltd. http://www.higarlics.com/newEbiz1/EbizPortalFG/portal/html/ProgramShow3.html?ProgramShow_ProgramID=c373e9167239ed628ffe0a538dcfe845. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Origin, History of cultivation". University of Georgia. http://www.uga.edu/fruit/apple.html. Retrieved 22 J a n u a r y 2008.

- ↑ Lauri, Pierre-éric; Karen Maguylo, Catherine Trottier (2006). "Architecture and size relations: an essay on the apple (Malus x domestica, Rosaceae) tree". American Journal of Botany (Botanical Society of America, Inc.) (93): 357–368.

- ↑ Coart, E., Van Glabeke, S., De Loose, M., Larsen, A.S., Roldán-Ruiz, I. 2006. Chloroplast diversity in the genus Malus: new insights into the relationship between the European wild apple (Malus sylvestris (L.) Mill.) and the domesticated apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). Mol. Ecol. 15(8): 2171-82.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "An apple a day keeps the doctor away". vegparadise.com. http://www.vegparadise.com/highestperch39.html. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1965) Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe, page 165 to 166. ISBN 0140136274

- ↑ Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1965) Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe, page 165 to 166. Penguin Books ISBN 0140136274

- ↑ Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1998) Roles of the Northern Goddess, page 146 to 147. Routledge ISBN 0415136105

- ↑ Sauer, Jonathan D. (1993). Historical Geography of Crop Plants: A Select Roster. CRC Press. pp. 109. ISBN 0849389011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Wasson, R. Gordon (1968). Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 128. ISBN 0-15-683800-1.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Ruck, Carl; Blaise Daniel Staples, Clark Heinrich (2001). The Apples of Apollo, Pagan and Christian Mysteries of the Eucharist. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 0-89089-924-X.

- ↑ Heinrich, Clark (2002). Magic Mushrooms in Religion and Alchemy. Rochester: Park Street Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 0-89281-997-9.

- ↑ Herodotus Histories 6.1.191.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Macrone, Michael; Tom Lulevitch (1998). Brush up your Bible!. Tom Lulevitch. Random House Value. ISBN 0517201895. OCLC 38270894.

- ↑ Elzebroek, A.T.G.; Wind, K. (2008). Guide to Cultivated Plants. Wallingford: CAB International. p. 27. ISBN 1845933567. http://books.google.com/?id=YvU1XnUVxFQC&lpg=PT39&dq=apple%20cultivars%207%2C500&pg=PT39#v=onepage&q=.

- ↑ "National Fruit Collections at Brogdale", Farm Advisory Services Team, accessed 2009-10-27

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Sue Tarjan (fall 2006). "Autumn Apple Musings" (pdf). News & Notes of the UCSC Farm & Garden, Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems. pp. 1–2. http://casfs.ucsc.edu/publications/news%20and%20notes/Fall_06_N&N.pdf. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "World apple situation". http://www.fas.usda.gov/htp2/circular/1998/98-03/applefea.html. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ↑ Weaver, Sue (June/July 2003). "Crops & Gardening - Apples of Antiquity". Hobby Farms magazine (BowTie, Inc). http://www.hobbyfarms.com/crops-and-gardening/fruit-crops-apples-14897.aspx.

- ↑ John Lloyd and John Mitchinson. (2006). QI: The Complete First Series - QI Factoids. [DVD]. 2 entertain.

- ↑ http://www.ces.ncsu.edu/fletcher/programs/nursery/metria/metria11/ranney/index.html

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Ferree, David Curtis; Ian J. Warrington (1999). Apples: Botany, Production and Uses. CABI Publishing. ISBN 0851993575. OCLC 182530169.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Bob Polomski; Greg Reighard. "Apple". Clemson University. http://hgic.clemson.edu/factsheets/HGIC1350.htm. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ "Apples". solarnavigator.net. http://www.solarnavigator.net/solar_cola/apples.htm. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ "Apples in Ecuador". Acta Hort. http://www.actahort.org/books/310/310_17.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ↑ S. Sansavini (1 July 1986). "The chilling requirement in apple and its role in regulating Time of flowering in spring in cold-Winter Climate". Symposium on Growth Regulators in Fruit Production (International ed.). Acta Horticulturae. pp. 179. ISBN 978-90-66051-82-9.

- ↑ "Controlled Atmosphere Storage (CA)". Washington State Apple Advertising Commission. http://www.bestapples.com/facts/facts_controlled.shtml. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ↑ "Food Science Australia Fact Sheet: Refrigerated storage of perishable foods". Food Science Australia. February, 2005. http://www.foodscience.csiro.au/refrigerated.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ↑ Pittsburgh Section, University of Pittsburgh School of Engineering, School of Engineering, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Pittsburgh Section, Instrument Society of America, Instrument Society of America Pittsburgh Section, University of Pittsburgh (1981). Modeling and Simulation: Proceedings of the Annual Pittsburgh Conference. Instrument Society of America.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Lowther, Granville; William Worthington. The Encyclopedia of Practical Horticulture: A Reference System of Commercial Horticulture, Covering the Practical and Scientific Phases of Horticulture, with Special Reference to Fruits and Vegetables. The Encyclopedia of horticulture corporation.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Coli, William et al.. "Apple Pest Management Guide". University of Massachusetts Amherst. http://www.umass.edu/fruitadvisor/NEAPMG/index.htm. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "How To Deal With Scab". GardenAction. http://www.gardenaction.co.uk/techniques/pests/scab.htm. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ↑ "Plant World - Heaviest Apple". Guinness World Records. http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/records/natural_world/plant_world/heaviest_apple.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Kristin Churchill. "Chinese apple-juice concentrate exports to United States continue to rise". Great American Publishing. http://www.fruitgrowersnews.com/pages/2004/issue04_10/04_10_ChinaJuice.html. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ Desmond, Andrew (1994). The World Apple Market. Haworth Press. pp. 144–149. ISBN 1560220414. OCLC 243470452.

- ↑ Gavin Evans (Tuesday, August 9, 2005). "Fruit ban rankles New Zealand - Australian apple growers say risk of disease justifies barriers". International Herald Tribune. http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/08/08/bloomberg/sxfruit.php. Retrieved 9 August 2005.

- ↑ FAO

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "Apples". Washington State Apple Advertising Commission. http://www.bestapples.com/varieties/varieties_foodsafety.shtml. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Boyer, J; Liu, RH; Rui Hai Liu (May 2004). "Apple phytochemicals and their health benefits". Nutrition journal (Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7201 USA: Department of Food Science and Institute of Comparative and Environmental Toxicology) 3: 5. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-3-5. PMID 15140261. PMC 442131. http://www.nutritionj.com/content/3/1/5.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Ames, Guy (July 2001). "Considerations in organic apple production" (pdf). National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service. http://attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/PDF/omapple.pdf. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ↑ Food Poisoning and Safety California Poison Control System

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 fallen apples – safe? iVillage Garden Web

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/f/food_allergy_apple/intro.htm

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/allergies/guide/food-allergy-treatments?page=2

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 For decreased risk of colon, prostate and lung cancer: "Nutrition to Reduce Cancer Risk". The Stanford Cancer Center (SCC). http://cancer.stanford.edu/information/nutritionAndCancer/reduceRisk/. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ For weight loss and cholesterol control: "Apples Keep Your Family Healthy". Washington State Apple Advertising Commission. http://www.bestapples.com/healthy/. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Rajeev Sharma. (2005). Improve your health with Apple,Guava,Mango. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd.. pp. 22. ISBN 8128809245.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 For prevention of dementia: Chan A, Graves V, Shea TB, A (Aug 2006). "Apple juice concentrate maintains acetylcholine levels following dietary compromise". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 9 (3): 287–291. ISSN 1387-2877. PMID 16914839.

- ↑ Phillips, John Pavin (1866-02-24). "A Pembrokeshire Proverb". Notes and Queries (Oxford University Press) s3-IX (217): 153. http://nq.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/s3-IX/217/153-d. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 "Apples Keep Your Family Healthy". Washington State Apple Advertising Commission. http://www.bestapples.com/healthy/. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ Lee KW, Lee SJ, Kang NJ, Lee CY, Lee HJ, KW (2004). "Effects of phenolics in Empire apples on hydrogen peroxide-induced inhibition of gap-junctional intercellular communication". Biofactors 21 (1–4): 361–5. doi:10.1002/biof.552210169. ISSN 0951-6433. PMID 15630226.

- ↑ Lee KW, Kim YJ, Kim DO, Lee HJ, Lee CY, KW (Oct 2003). "Major phenolics in apple and their contribution to the total antioxidant capacity". J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (22): 6516–6520. doi:10.1021/jf034475w. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 14558772.

- ↑ Juniper BE, Mabberley DJ (2006). The Story of the Apple. Timber Press. pp. 20. ISBN 0881927848.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain 1911 edition of The Grocer's Encyclopedia.

External links

- Apples at the Open Directory Project

- Apple Facts from the UK's Institute of Food Research

- Grand Valley State University digital collections- diary of Ohio fruit farmer Theodore Peticolas, 1863

- National Fruit Collection (UK)

- Brogdale Farm (home of the UK's National Fruit Collection)

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Apple". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Apple". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Tree Guide - Lodi Apple

- Tree Guide - Red Delicious Apple

- Tree Guide - Jonathan Apple

- Tree Guide - Winesap Apple

- Tree Guide - Yellow Delicious

|

|||||||||||||