Aphid

| Aphids Fossil range: Permian–Present |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Aphids feeding on a fennel stalk | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Suborder: | Sternorrhyncha |

| Superfamily: | Aphidoidea |

| Families | |

|

There are 10 families:

|

|

Aphids, also known as plant lice and in Britain and the Commonwealth as greenflies, blackflies or whiteflies,[1] are small sap sucking insects, and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea.[2] Aphids are among the most destructive insect pests on cultivated plants in temperate regions.[3] The damage they do to plants has made them enemies of farmers and gardeners the world over, but from a zoological standpoint they are a very successful group of organisms.[4]

About 4,400 species of 10 families are known. Historically, many fewer families were recognized, as most species were included in the family Aphididae. Around 250 species are serious pests for agriculture and forestry as well as an annoyance for gardeners. They vary in length from one to ten millimetres.

Natural enemies include predatory lady beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), hoverfly larvae (Diptera: Syrphidae), parasitic wasps, aphid midge larvae, crab spiders[5] lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), and entomopathogenic fungi like Lecanicillium lecanii and the Entomophthorales.

Contents |

Distribution

Aphids are distributed worldwide, but are most common in temperate zones. Also, in contrast to many taxa, species diversity is much lower in the tropics than in the temperate zones. They can migrate great distances, mainly through passive dispersal by riding on winds. For example, the currant lettuce aphid (Nasonovia ribisnigri) is believed to have spread from New Zealand to Tasmania in this way.[6] Aphids have also been spread by human transportation of infested plant materials.

Taxonomy

Aphids are in the superfamily Aphidoidea in the homopterous division of the order Hemiptera. Recent classification within Hemiptera has reduced the old taxon "Homoptera" to two suborders: Sternorrhyncha (e.g., aphids, whiteflies, scales, psyllids, etc.) and Auchenorrhyncha (e.g., cicadas, leafhoppers, treehoppers, planthoppers, etc.) with the suborder Heteroptera containing a large group of insects known as the true bugs. More recent reclassifications have substantially rearranged the families within Aphidoidea: some old families were reduced to subfamily rank (e.g., Eriosomatidae), and many old subfamilies elevated to family rank. Taxonomically woolly conifer aphids like the pine aphid, the spruce aphid and the balsam woolly aphid are not true aphids, but adelgids, and lack the cornicles of true aphids.

Relation to phylloxera and adelgids

Aphids, adelgids, and phylloxerids are very closely related, and are either placed in the insect super family Aphidoidea (Blackman and Eastop, 1994) or into two super families (Phylloxeroidea and Aphidoidea) within the order Homoptera, the plant-sucking bugs.[7]

Like aphids, phylloxera feed on the roots, leaves and shoots of grape plants, but unlike aphids do not produce honeydew or cornicle secretions.[8] Phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae), are insects which caused the Great French Wine Blight that devastated European viticulture in the 19th century.

Similarly, adelgids also feed on plant phloem. Adelgids are sometimes described as aphids, but more properly as classified as aphid-like insects, because they have no cauda or cornicles.[3]

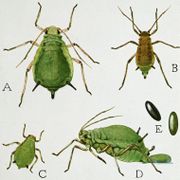

Anatomy

Most aphids have soft bodies, which may be green, black, brown, pink or almost colourless. Aphids have antennae with as many as six segments.[3] Aphids feed themselves through sucking mouthparts called stylets, enclosed in a sheath called a rostrum, which is formed from modifications of the mandible and maxilla of the insect mouthparts.[9] They have long, thin legs and two-jointed, two-clawed tarsi.

Most aphids have a pair of cornicles (or "siphunculi"), abdominal tubes through which they exude droplets of a quick-hardening defensive fluid[9] containing triacylglycerols, called cornicle wax. Other defensive compounds can also be produced by some types of aphids.[3]

Aphids have a tail-like protrustion called a "cauda" above their rectal apertures. They have two compound eyes, and an ocular tubercle behind and above each eye, made up of three lenses (called triommatidia).[10][11]

When host plant quality becomes poor or conditions become crowded, some aphid species produce winged offspring, "alates", that can disperse to other food sources. The mouthparts or eyes are smaller or missing in some species and forms.[3]

Diet

Many aphid species are monophagous (that is, they feed on only one plant species). Others, like the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae), feed on hundreds of plant species across many families.

Aphids passively feed on sap of phloem vessels in plants, as do many of their fellow members of Hemiptera such as scale insects and cicadas. Once a phloem vessel is punctured, the sap, which is under high pressure, is forced into the aphid's food canal. Occasionally, aphids also ingest xylem sap, which is a more dilute diet than phloem sap as the concentration of sugars and amino acids are 1% of those in the phloem.[12][13] Xylem sap is under negative hydrostatic pressure and requires active sucking , suggesting an important role in aphid physiology.[14] As xylem sap ingestion has been observed following a dehydration period, it was suspected that aphids consume xylem sap to replenish their water balance; the consumption of the dilute sap of xylem permitting aphids to rehydrate.[15] However, recent data showed that aphids consume more xylem sap than expected and that they notably do so when they are not dehydrated and when their fecundity decreases.[16] This suggests that aphids, and potentially, all the phloem-sap feeding species of the order Hemiptera, consume xylem sap for another reason than replenishing water balance. It was suggested that xylem sap consumption is related to osmoregulation.[16]

Plant sap is an unbalanced diet for aphids as it lacks essential amino acids, which aphids, like all animals, cannot synthesize, and possesses a high osmotic pressure due to its high sucrose concentration.[13][17] Essential amino acids are provided to aphids by bacterial endosymbionts, harboured in special cells, bacteriocytes.[18] These symbionts recycle the metabolic waste of their host, glutamate, into essential amino acids.[19][20] High osmotic pressure in the stomach, caused by high sucrose concentration, can lead to water transfer from the hemolymph to the stomach, thus resulting in hyperosmotic stress and eventually to the death of the insect. Aphids avoid this fate by osmoregulating through several processes. Sucrose concentration is directly reduced by assimilating sucrose toward metabolism and by synthesizing oligosaccharides from several sucrose molecules, thus reducing the solute concentration and consequently the osmotic pressure.[21][22] Oligasaccharides are then excreted through honeydew, explaining its high sugar concentrations, which can then be used by other animals such as ants. Furthermore, water is transferred from the hindgut, where omostic pressure has already been reduced, to the stomach to dilute stomach content.[23] Eventually, aphids consume xylem sap to dilute the stomach osmotic pressure.[16] All these processes function synergetically, and enable aphids to feed on high sucrose concentration plant sap as well as to adapt to varying sucrose concentrations.

As they feed, aphids often transmit plant viruses to the plants, such as to potatoes, cereals, sugarbeets and citrus plants.[9] These viruses can sometimes kill the plants.

Symbioses

Ant mutualism

Some species of ants "farm" aphids, protecting them on the plants they eat, eating the honeydew that the aphids release from the terminations of their alimentary canals. This is a "mutualistic relationship".

These "dairying ants" "milk" the aphids by stroking them with their antennae.[24][25] Therefore, sometimes aphids are called "ant cows".

Some farming ant species gather and store the aphid eggs in their nests over the winter. In the spring, the ants carry the newly hatched aphids back to the plants. Some species of dairying ants (such as the European yellow meadow ant, Lasius flavus)[26] manage large "herds" of aphids that feed on roots of plants in the ant colony. Queens that are leaving to start a new colony take an aphid egg to find a new herd of underground aphids in the new colony. These farming ants protect the aphids by fighting off aphid predators.[25]

An interesting variation in ant-aphid relationships involves Lycaenid butterflies (such as the Sievers blue butterfly and the Japanese copper butterfly) and the Myrmica ants. For example, Niphanda fusca butterflies lay eggs on plants where ants tend herds of aphids. The eggs hatch as caterpillars which feed on the aphids. The ants do not defend the aphids from the caterpillars, but carry the caterpillars to their nest. In the nest, the ants feed the caterpillars, which produce honeydew for the ants. When the caterpillars reach full size, they crawl to the colony entrance and form cocoons. After two weeks, butterflies emerge and take flight.[27]

Some bees in coniferous forests also collect aphid honeydew to make "forest honey".[9]

Bacterial endosymbiosis

Endosymbiosis with micro-organism is common in insects, with more than 10% of insect species relying upon intracellular bacteria for their development and survival [28] Aphids harbour a vertically transmitted (from parent to its offspring) obligate symbiosis with Buchnera aphidicola (Buchner) (Proteobacteria: Enterobacteriaceae), referred to as the primary symbiont, which is located inside specialized cells, the bacteriocytes.[29] The original contamination occurred in a common ancestor 160 to 280 million years ago and has enabled aphids to exploit a new ecological niche, phloem-sap feeding on vascular plants. Buchnera aphidicola provides its host with essential amino acids, which are present in low concentrations in plant sap. The stable intracellular conditions as well as the bottleneck effect experienced during the transmission of a few bacteria from the mother to each nymph increase the probability of transmission of mutations and gene deletions.[30][31] As a result the size of the B. aphidicola genome is greatly reduced, compared to its putative ancestor.[32] Despite the apparent loss of transcription factors in the reduced genome, gene expression is highly regulated, as shown by the 10-fold variation in expression levels between different genes under normal conditions.[33] Buchnera aphidicola gene transcription, although not well understood, is thought to be regulated by a small number of global transcriptional regulators and/or through nutrient supplies from the aphid host.

Some aphid colonies also harbour other bacterial symbionts, referred to as secondary symbionts due to their facultative status. They are vertically transmitted, although some studies demonstrated the possibility of horizontal transmission (from one lineage to another and possibly from one species to another). [34][35] So far, the role of only some of the secondary symbionts has been described; Regiella insecticola plays a role in defining the host-plant range [36][37], Hamiltonella defensa provides resistance to parasitoids [38], and Serratia symbiotica prevents the deleterious effects of heat.[39]

Unique ability to synthesize carotenoids

Some species of aphids have acquired the ability to synthesize red carotenoids, by horizontal gene transfer from fungi. This allows otherwise green aphids to be colored red. Aphids are the only known member of the animal kingdom with the ability to synthesize carotenoids.[40]

Reproduction

Some aphid species have unusual and complex reproductive adaptations, while others have fairly simple reproduction. Adaptations include having both sexual and asexual reproduction, creation of eggs or live nymphs and switches between woody and herbaceous types of host plant at different times of the year.[3][41]

Many aphids undergo cyclical parthenogenesis. In the spring and summer, mostly or only females are present in the population. The overwintering eggs that hatch in the spring result in females, called fundatrices. Reproduction is typically parthenogenetic and viviparous. Females undergo a modified meiosis that results in eggs that are genetically identical to their mother (parthenogenetic). The embryos develop within the mothers' ovarioles, which then give live birth to first instar female nymphs (viviparous). The offspring resemble their parent in every way except size, and are called virginoparae.

This process iterates throughout the summer, producing multiple generations that typically live 20 to 40 days. Thus one female hatched in spring may produce many billions of descendants. For example, some species of cabbage aphids (like Brevicoryne brassicae) can produce up to 41 generations of females.

In autumn, aphids undergo sexual, oviparous reproduction. A change in photoperiod and temperature, or perhaps a lower food quantity or quality, causes females to parthenogenetically produce sexual females and males. The males are genetically identical to their mothers except that they have one less sex chromosome. These sexual aphids may lack wings or even mouthparts.[3] Sexual females and males mate, and females lay eggs that develop outside the mother. The eggs endure the winter and emerge as winged or wingless females the following spring. This is, for example, the life cycle of the rose aphid (Macrosiphum rosae, or less commonly Aphis rosae), which may be considered typical of the family. However in warm environments, such as in the tropics or in a greenhouse, aphids may go on reproducing asexually for many years.[9]

Some species produce winged females in the summer, sometimes in response to low food quality or quantity. The winged females migrate to start new colonies on a new plant, often of quite a different kind. For example, the apple aphid (Aphis Mali), after producing many generations of wingless females on its typical food-plant, gives rise to winged forms which fly away and settle on grass or corn-stalks.

Some aphids have telescoping generations. That is, the parthenogenetic, viviparous female has a daughter within her, who is already parthenogenetically producing her own daughter. Thus a female's diet can affect the body size and birth rate of more than two generations (daughters and granddaughters).[42][43]

Evolution

Aphids probably appeared around 280 million years ago, in the early Permian period. They probably fed on plants like Cordaitales or Cycadophyta. The oldest known aphid fossil is of the species Triassoaphis cubitus Evans from the Triassic.[44] The number of species was small, but increased considerably with the appearance of angiosperms 160 million years ago. Angiosperms allowed aphids to specialize. Organs like the cornicles did not appear until the Cretaceous period.

Threats

Aphids are soft-bodied, and have a wide variety of insect predators. Aphids also are often infected by bacteria, viruses and fungi. Aphids are affected by the weather, such as precipitation,[45] temperature[46] and wind.[47]

Insects that attack aphids include predatory lady bugs (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) (ladybirds in the UK), hoverfly larvae (Diptera: Syrphidae), parasitic wasps, aphid midge larvae, aphid lions, crab spiders[5] and lacewings (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae).

Fungi that attack aphids include Neozygites fresenii, Entomophthora, Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae and entomopathogenic fungi like Lecanicillium lecanii. Aphids brush against the microscopic spores. These spores stick to the aphid, germinate and penetrate the aphid's skin. The fungus grows in the aphid hemolymph (i.e., the counterpart of blood for aphids). After about 3 days, the aphid dies and the fungus releases more spores into the air. Infected aphids are covered with a woolly mass that progressively grows thicker until the aphid is obscured. Often the visible fungus is not the type of fungus that killed the aphid, but a secondary fungus.[45]

Aphids can be easily killed by unfavorable weather, such as late spring freezes.[48] Excessive heat kills the symbiotic bacteria that some aphids depend on, which makes the aphids infertile.[49] Rain prevents winged aphids from dispersing, and knocks aphids off plants and thus kills them from the impact or by starvation.[45][50][51] However, Ken Ostlie, an entomologist with the University of Minnesota Extension Service, suggests that rain should not be relied on for aphid control.[52]

Defenses

Aphids are soft-bodied, and have little protection from predators and diseases. Some species of aphid interact with plant tissues forming a gall, an abnormal swelling of plant tissue. Aphids can live inside the gall, which provides protection from predators and the elements. A number of galling aphid species are known to produce specialised "soldier" forms, sterile nymphs with defensive features which defend the gall from invasion.[9][54] For example, Alexander's horned aphids are a type of soldier aphid that has a hard exoskeleton and pincer-like mouthparts.[55] Infestation of a variety of Chinese trees by Chinese sumac aphids (Melaphis chinensis Bell) can create a "Chinese gall" which is valued as a commercial product. As "Galla Chinensis", Chinese galls are used in Chinese medicine to treat coughs, diarrhea, night sweats, dysentry and to stop intestinal and uterine bleeding. Chinese galls are also an important source of tannins.[9]

Some species of aphid, known as "woolly aphids" (Eriosomatinae), excrete a "fluffy wax coating" for protection.[9]

The cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae) stores and releases chemicals that produce a violent chemical reaction and strong mustard oil smell to repel predators.

It was common at one time to suggest that the cornicles were the source of the honeydew, and this was even included in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary[56] and the 2008 edition of the World Book Encyclopedia.[57]. In fact, honeydew secretions are produced from the anus of the aphid[58], while cornicles mostly produce defensive chemicals such as waxes. There also is evidence of cornicle wax attracting aphid predators in some cases.[59] Aphids are also known to defend themselves from attack by parasitoid wasps by kicking.

Effects on plants

Plants exhibiting aphid damage can have a variety of symptoms, such as decreased growth rates, mottled leaves, yellowing, stunted growth, curled leaves, browning, wilting, low yields and death. The removal of sap creates a lack of vigour in the plant, and aphid saliva is toxic to plants. Aphids frequently transmit disease-causing organisms like plant viruses to their hosts. The green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) is a vector for more than 110 plant viruses. Cotton aphids (Aphis gossypii) often infect sugarcane, papaya and groundnuts with viruses.[3] Aphids contributed to the spread of late blight (Phytophthora infestans) among potatoes in the Great Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s.[60]

The cherry aphid or black cherry aphid, Myzus cerasi, is responsible for some leaf curl of cherry trees. This can easily be distinguished from 'leaf curl' caused by Taphrina fungus species due to the presence of aphids beneath the leaves.

The coating of plants with honeydew can contribute to the spread of fungi which can damage plants.[61][62][63] Honeydew produced by aphids has been observed to reduce the effectiveness of fungicides as well.[64]

A hypothesis that insect feeding may improve plant fitness was floated in the mid-1970s by Owen and Wiegert. It was felt that the excess honeydew would nourish soil micro-organisms, including nitrogen fixers. In a nitrogen poor environment, this could provide an advantage to an infested plant over a noninfested plant. However, this does not appear to be supported by the observational evidence.[65]

The damage of plants, and in particular commercial crops, has resulted in large amounts of resources and efforts being spent attempting to control the activities of aphids.[3]

Control of aphids

There are various insecticides that can be used to control aphids. Nowadays, there are many plant extracts and plant products that are eco-friendly and control aphids as effectively as chemical insecticides. Shreth et al. suggested use of Neem products and Lantana products to protect plants against aphids.[66]

Alternatively, biological control can be used, this involves using a natural predator, such as lacewings to control the population of aphids. The predator is introduced as eggs or larvae which then develop by eating aphids, bringing down aphid population. The adult lacewings survive on pollen.

Integrated pest management of various species of aphids can be achieved using biological insecticides based on microbes such as Beauveria bassiana or Paecilomyces fumosoroseus.

Synthesized neuropeptide analogues are another form of biological control is being explored by researchers at the Agricultural Research Service. Neuropeptide is a chemical signal that aphids use to regulate and control body functions such as digestion, respiration, and water intake. Researchers want to alter the molecular structure of neuropeptide so that it cannot be broken down by other enzymes, therefore disrupting the body functions that the chemical controls. In experimental tests, one neuropeptide mimic killed 90-100% of the aphids within three days.[67] The neuropeptide mimic’s rate of mortality is comparable to commercial insecticides; however, the mimic must be thoroughly tested before it can ever be used as a effective biological agent. [2]

See also

- Aeroplankton

- Pineapple gall

- Economic entomology

References

- Monograph of the British Aphides, Volumes I-IV, George Bowdler Buckton, Ray Society, 1876-1883.

- ↑ Not to be confused with "jumping plant lice"

- ↑ (McGavin, George C. (1993). Bugs of the World. Facts on File. p. 86. http://factsonfile.com.)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Bugs of the World, George C. McGavin, Facts on File, 1993, ISBN 0816027374

- ↑ Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press. pp. 6–9. ISBN 978–0–313–33922–6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Photo of crab spider eating Aphis asclepiadis aphids on common milkweed, Anurag Agrawal, Phytophagy Laboratory, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Department of Entomology at Cornell University.

- ↑ Courtney, Pip (October 30, 2005). "Scientist battles lettuce aphid". Landline, Australian Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.abc.net.au/landline/content/2005/s1493620.htm. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ↑ Aphid Ecology - An optimization approach, Second Edition, A.F.G. Dixon, Springer; 2nd ed. edition (1997), ISBN 0412741806

- ↑ Biology and Management of Grape Phylloxera, Jeffrey Granett, M. Andrew Walker,Laszlo Kocsis, and Amir D. Omer, Annual Review of Entomology, Vol. 46: 387-412, January 2001, doi 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.387

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Aphid, Henry G. Stroyan, McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, 8th Edition, 1997, ISBN 0-07-911504-7

- ↑ Molecular Studies of the Salivary Glands of the Pea Aphid, Acyrthosiphon Pisum (Harris), Navdeep S. Mutti, PhD Thesis, Kansas State University, 2006.

- ↑ Aphid Ecology, A. F. G. Dixon, Chapman and Hall, 1998, ISBN 0412741806

- ↑ Spiller, N. J., Koenders, L. & Tjallingii, W. F. (1990) Xylem ingestion by aphids — a strategy for maintaining water balance. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 55:101-104

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Fisher, D. B. 2000. Long distance transport, pp. 730-784. In B. B. Buchanan and Gruissem [eds.], Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, USA.

- ↑ Malone, M., R. Watson, and J. Pritchard. 1999. The spittlebug Philaenus spumarius feeds from mature xylem at the full hydraulic tension of the transpiration stream. New Phytologist 143: 261-271.

- ↑ Powell, G., and J. Hardie. 2002. Xylem ingestion by winged aphids. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 104: 103-108.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Pompon, J., D. Quiring, P. Giordanengo, and Y. Pelletier. 2010. Role of xylem consumption on osmoregulation in Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas). Journal of Insect Physiology 56: 610-615.

- ↑ Dadd, R. H., and T. E. Mittler. 1965. Studies on the artificial feeding of the aphid Myzus persicae (Sulzer)-III. Some major nutritional requirements. Journal of Insect Physiology 11: 717-743.

- ↑ Buchner, P. 1965. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms. Interscience.

- ↑ Whitehead, L. F., and A. E. Douglas. 1993. A metabolic study of Buchnera, the intracellular bacterial symbionts of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Journal of General Microbiology 139: 821-826.

- ↑ Febvay, G., I. Liadouze, J. Guillaud, and G. Bonnot. 1995. Analysis of energetic amino acid metabolism in Acyrthosiphon pisum: A multidimensional approach to amino acid metabolism in aphids. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 29: 45-69.

- ↑ Ashford, D. A., W. A. Smith, and A. E. Douglas. 2000. Living on a high sugar diet: The fate of sucrose ingested by a phloem-feeding insect, the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Journal of Insect Physiology 46: 335-341.

- ↑ Wilkinson, T. L., D. A. Ashford, J. Pritchard, and A. E. Douglas. 1997. Honeydew sugars and osmoregulation in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Journal of Experimental Biology 200: 2137-2143.

- ↑ Shakesby, A. J., I. S. Wallace, H. V. Isaacs, J. Pritchard, D. M. Roberts, and A. E. Douglas. 2009. A water-specific aquaporin involved in aphid osmoregulation. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 39: 1-10.

- ↑ There are also dairying ants that "milk" mealybugs and other insects.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ant, Linda M. Hooper-Bui, World Book Encyclopedia, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7166-0108-1

- ↑ Insects of the World, Anthony Wootton, Blandford, Cassell Plc, 1984, reprinted 1999, ISBN 0713723661

- ↑ pages 78 and 79 of Insects and Spiders, Time-Life Books, ISBN 0809496879

- ↑ Baumann, P., N. A. Moran, and L. Baumann. 2000. Bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of insects. The Prokaryotes (Online)

- ↑ Douglas, A E (1998). "Nutritional interctions in insect-microbial symbioses: Aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera". Annual Review of Entomology 43: 17[][]8. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.17. ISSN 00664170. PMID 15012383.

- ↑ Pérez-Brocal, V., R. Gil, S. Ramos, A. Lamelas, M. Postigo, J. M. Michelena, F. J. Silva, A. Moya, and A. Latorre. 2006. A small microbial genome: The end of a long symbiotic relationship? Science 314: 312-313.

- ↑ Mira, A., and N. A. Moran. 2002. Estimating population size and transmission bottlenecks in maternally transmitted endosymbiotic bacteria. Microbial Ecology 44: 137-143.

- ↑ Shigenobu, S., H. Watanabe, M. Hattori, Y. Sakaki, and H. Ishikawa. 2000. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature 407: 81-86.

- ↑ Viñuelas, J., F. Calevro, D. Remond, J. Bernillon, Y. Rahbé, G. Febvay, J. M. Fayard, and H. Charles. 2007. Conservation of the links between gene transcription and chromosomal organization in the highly reduced genome of Buchnera aphidicola. BMC Genomics 8.

- ↑ Tsuchida, T., R. Koga, X. Y. Meng, T. Matsumoto, and T. Fukatsu. 2005. Characterization of a facultative endosymbiotic bacterium of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Microbial Ecology 49: 126-133.

- ↑ Sakurai, M., R. Koga, T. Tsuchida, X. Y. Meng, and T. Fukatsu. 2005. Rickettsia symbiont in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum: Novel cellular tropism, effect on host fitness, and interaction with the essential symbiont Buchnera. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71: 4069-4075.

- ↑ Ferrari, J., C. Scarborough, and H. Godfray. 2007. Genetic variation in the effect of a facultative symbiont on host-plant use by pea aphids. Oecologia 153: 323-329.

- ↑ Simon, J. C., S. Carré, M. Boutin, N. Prunier-Leterme, B. Sabater-Mun, A. Latorre, and R. Bournoville. 2003. Host-based divergence in populations of the pea aphid: insights from nuclear markers and the prevalence of facultative symbionts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 270: 1703-1712.

- ↑ Oliver, K. M., N. A. Moran, and M. S. Hunter. 2006. Costs and benefits of a superinfection of facultative symbionts in aphids. Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society 273: 1273-1280.

- ↑ Burke, G., O. Fiehn, and N. Moran. 2009. Effects of facultative symbionts and heat stress on the metabolome of pea aphids. ISME Journal.

- ↑ N.A. Moran1 and T. Jarvik. Lateral Transfer of Genes from Fungi Underlies Carotenoid Production in Aphids. Science, 30 April 2010: Vol. 328. no. 5978, pp. 624 - 627 DOI: 10.1126/science.1187113 Abstract [1] accessed April 30, 2010.]

- ↑ About 10% of aphid species produce generations that alternate between woody and herbaceous plants (page 87 of Bugs of the World, George C. McGavin, Facts on File, 1993).

- ↑ Effect of nitrogen fertilization on Aphis gossypii (Homoptera: Aphididae): variation in size, color, and reproduction, E. Nevo and M. Coll, J. Econ. Entomol. 94: 27-32, 2001.

- ↑ Effect of nitrogen fertilizer on the intrinsic rate of increase of the rusty plum aphid, Hysteroneura setariae (Thomas) (Homoptera: Aphididae) on rice (Oryza sativa L.), G. C. Jahn, L. P. Almazan, and J. Pacia, Environmental Entomology 34 (4): 938-943, 2005.

- ↑ Acropyga and Azteca Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with Scale Insects (Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea): 20 Million Years of Intimate Symbiosis, Christine Johnson, Dant Agosti, Jacques H. Delabie, Klaus Dumpert, D.J. Williams, Michael von Tschirnhaus and Ulrich Maschwitz, American Museum Novitates, June 22, 2001.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Early Season Aphid and Thrips Populations, Gerald E. Brust, University of Maryland, College Park College of Agriculture and Natural Resources News Article, June 22, 2006

- ↑ Some Effects of Fluctuating Temperatures on Metabolism, Development, and Rate of Population Growth in the Cabbage Aphid, Brevicoryne Brassicae, K. P. Lamb, Ecology, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Oct., 1961), pp. 740-745

- ↑ Abundance of Aphids on Cereals from Before 1973 to 1977, Margaret G. Jones, The Journal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Apr., 1979), pp. 1-22

- ↑ Soybean Aphid, A New Beginning for 2007, Christian Krupke, John Obermeyer, and Robert O[][]eil, Pest and Crop, May 11, 2007 - Issue 7, Purdue Extension Service.

- ↑ Why Some Aphids Can't Stand The Heat, Science Daily, April 23, 2007.

- ↑ Population Dynamics of the Cabbage Aphid, Brevicoryne brassicae (L.), R. D. Hughes, The Journal of Animal Ecology, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Oct., 1963), pp. 393-424

- ↑ Stable Age Distributions of Lucerne Aphid Populations in SE-Tasmania, S. Suwanbutr, page 38-43, Thammasat International Journal of Science and Technology, Vol 1, No. 5, 1996

- ↑ Spider Mites, Aphids and Rain Complicating Spray Decisions in Soybean, Ken Ostlie, Minnesota Crop eNews, University of Minnesota Extension Service, August 3, 2006

- ↑ The fourteen-spotted lady beetles are also known as "P-14 lady beetles", or propylea quatuordecimpunctata.

- ↑ Aoki, S. (1977) Colophina clematis (Homoptera, Pemphigidae), an aphid species with soldiers. Kontyu 45, 276[][]82

- ↑ page 144 of Insects and Spiders, Time-Life Books, ISBN 0809496879

- ↑ Defence by Smear: Supercooling in the Cornicle Wax of Aphids, John S. Edwards, Letters to Nature, Nature, 211, 73 - 74, 02 July 1966; doi:10.1038/211073a0

- ↑ Aphid, Candace Martinson, World Book Encyclopedia, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7166-0108-1

- ↑ Mutualism between ants and honeydew producing homoptera. MJ Way. Annual Review of Entomology

- ↑ Kairomonal effect of an aphid cornicle secretion onLysiphlebus testaceipes (Cresson) (Hymenoptera: Aphidiidae), Tessa R. Grasswitz and Timothy D. Paine, Journal of Insect Behavior, Springer Netherlands, ISSN 0892-7553 (Print) 1572-8889 (Online), Issue Volume 5, Number 4 / July, 1992, DOI 10.1007/BF01058190

- ↑ page 61 of The Most Extreme Bugs, Catherine Nichols, Forward by Kevin Mohs and Ian McGee, Jossey-Bass, John Wiley and Sons, 2007, ISBN 9780787986636

- ↑ Sooty mold fungus growing on honeydew deposited on lower sugarcane leaves by yellow sugarcane aphids, Sipha flava (Forbes), University of Florida

- ↑ Sooty mold, Daniel H. Gillman, University of Massachusetts Extension, Fall 2005

- ↑ Scorias spongiosa, the beech aphid poop-eater, Hannah T. Reynolds and Tom Volk, Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month, University of Wisconsin–La Crosse, September 2007

- ↑ Interaction between phyllosphere yeasts, aphid honeydew and fungicide effectiveness in wheat under field conditions, J. Dika and J. A. Van Pelt, Plant pathology, vol. 41, no6, pp. 661-675 (1 p.), 1992, ISSN 0032-0862 CODEN PLPAAD

- ↑ Aphid Honeydew: A re-appraisal of the hypothesis of Owen and Wiegert, Dhurpad Choudhury, Oikos, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Oct., 1985), pp. 287-290

- ↑ page 11-13 of Laboratory Evaluation of Certain Cow Urine Extract of Indigenous Plants Against Mustard Aphid, Lipaphis erysimi (Kaltenbach) Infesting Cabbage, Chongtham Narajyot Shreth, Kh. Ibohal and S. John William, Hexapoda, 2009

- ↑ "Algae: Using a Pest’s Chemical Signals to Control It". USDA Agricultural Research Service. May 17, 2010. http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/pr/2010/100517.htm.

External links

- Aphids of southeastern U.S. woody ornamental

- Acyrthosiphon pisum at MetaPathogen: facts, life cycle, life cycle image

- Agricultural Research Service Sequenced Genome of Pea Aphid

- Insect Olfaction of Plant Odour: Colorado Potato Beetle and Aphid Studies

On the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site:

- Aphis gossypii, melon or aphid

- Aphis nerii, oleander aphid

- Hyadaphis coriandri, corianderaphid

- Longistigma caryae, giant bark aphid

- Myzus persicae, green peach aphid

- Sarucallis kahawaluokalani, crapemyrtle aphid

- Shivaphis celti, an Asian woolly hackberry aphid

- Toxoptera citricida, brown citrus aphid

- Asain Wooly Hackberry Aphid - Center for Invasive Species Research