Anti-gravity

In physical cosmology, astronomy and celestial mechanics, anti-gravity is the idea of creating a place or object that is free from the force of gravity. It does not refer to the lack of weight under gravity experienced in free fall or orbit, nor to balancing the force of gravity with some other force, such as electromagnetism or aerodynamic lift.

Instead, anti-gravity requires that the fundamental causes of the force of gravity be made either not present or not applicable to the place or object through some kind of technological intervention. Anti-gravity is a recurring concept in science fiction, particularly in the context of spacecraft propulsion. The concept was first introduced formally as "Cavorite" in H. G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon, and has been a favorite item of imaginary technology since that day.

In the first mathematically accurate description of gravity, Newton's law of universal gravitation, gravity was an external force transmitted by unknown means. However in the early part of the 20th century Newton's model was replaced by the more general and complete description known as general relativity. In general relativity, gravity is not a force in the traditional sense of the word, but the result of the geometry of space itself. These geometrical solutions always cause attractive "forces". Under general relativity, anti-gravity is highly unlikely, except under contrived circumstances that are regarded as unlikely or impossible. The term "anti-gravity" is also sometimes used to refer to hypothetical reactionless propulsion drives based on certain solutions to general relativity, although these do not oppose gravity as such.

There are numerous newer theories that add onto general relativity or replace it outright, and some of these appear to allow anti-gravity-like solutions. However, according to the current generally accepted physical theories and according to the some directions of physical research, it is considered by some unlikely that anti-gravity is possible.[1][2][3]

The terminology "anti-gravity" is often used in popular culture as a colloquialism to refer to devices that look as if they reverse gravity even though they operate through other means. Lifters, which fly in the air due to electromagnetic fields, are an example of these "antigravity craft".[4][5]

Contents |

Hypothetical solutions

Gravity shields

One might consider the results of placing such a substance under one-half of a wheel on a shaft. The side of the wheel above the substance would have no weight, while the other side would. This would cause the wheel to continually "fall" toward the side above the plate. This motion could be harnessed to produce power for free, a clear violation of the first law of thermodynamics. More generally, it follows from Gauss's law that static inverse-square fields (such as Earth's gravitational field) cannot be blocked (magnetism is static, but is inverse-cube). Under general relativity, the entire concept is something of a non-sequitur.

In 1948 successful businessman Roger Babson (founder of Babson College) formed the Gravity Research Foundation to study ways to reduce the effects of gravity.[6] Their efforts were initially somewhat "crankish", but they held occasional conferences that drew such people as Clarence Birdseye of frozen-food fame and Igor Sikorsky, inventor of the helicopter. Over time the Foundation turned its attention away from trying to control gravity, to simply better understanding it. The Foundation disappeared some time after Babson's death in 1967. However, it continues to run an essay award, offering prizes of up to $5,000. As of 2007, it is still administered out of Wellesley, Massachusetts by George Rideout, Jr., son of the foundation's original director. Recent winners include California astrophysicist George F. Smoot, who later won the 2006 Nobel Prize in physics.

General relativity research in the 1950s

General relativity was introduced in the 1910s, but development of the theory was greatly slowed by a lack of suitable mathematical tools. Some of these were introduced in the 1950s, and by the 1960s a flowering of general relativity was underway that later became known as the golden age of general relativity. Although it appeared that anti-gravity was outlawed under general relativity, there were a number of efforts to study potential solutions that allowed anti-gravity-type effects.

It is claimed the US Air Force also ran a study effort throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s.[7] Former Lieutenant Colonel Ansel Talbert wrote two series of newspaper articles claiming that most of the major aviation firms had started gravity control propulsion research in the 1950s. However there is little outside confirmation of these stories, and since they take place in the midst of the policy by press release era, it is not clear how much weight these stories should be given.

It is known that there were serious efforts underway at the Glenn L. Martin Company, who formed the Research Institute for Advance Study.[8][9] Major newspapers announced the contract that had been made between theoretical physicist Burkhard Heim and the Glenn L. Martin Company. Other private sector efforts to master the understanding of gravitation was the creation of the Institute for Field Physics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in 1956 by Gravity Research Foundation trustee, Agnew H. Bahnson.

Military support for anti-gravity projects was terminated by the Mansfield Amendment of 1973, which restricted Department of Defense spending to only the areas of scientific research with explicit military applications. The Mansfield Amendment was passed specifically to end long-running projects that had little to show for their efforts.

Negative mass

Under general relativity, gravity is the result of following a spatial geometry (change in the normal shape of space) caused by local mass-energy. This theory holds that it is the altered shape of space, deformed by massive objects, that causes 'gravity', which is actually a property of deformed space rather than being a true force. Although the equations cannot produce a "negative geometry" normally, it is possible to do so using a "negative mass". The same equations do not, of themselves, rule out the existence of negative mass.

Both general relativity and Newtonian gravity appear to predict that negative mass would produce a repulsive gravitational field. In particular, Sir Hermann Bondi proposed in 1957 that negative gravitational mass, combined with negative inertial mass, would comply with the strong equivalence principle of general relativity theory and the Newtonian laws of conservation of linear momentum and energy. Bondi's proof yielded singularity free solutions for the relativity equations.[10] In July 1988, Robert L. Forward presented a paper at the AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE 24th Joint Propulsion Conference that proposed a Bondi negative gravitational mass propulsion system.[11]

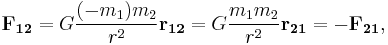

Every point mass attracts every other point mass by a force pointing along the line intersecting both points. The force is proportional to the product of the two masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the point masses:

where:

is the magnitude of the gravitational force between the two point masses,

is the magnitude of the gravitational force between the two point masses,- G is the gravitational constant,

- |m1| >0 is the (negative) mass of the first point mass, the minus is put out to show negative force, m1 is actually <0

- m2 >0 is the mass of the second point mass,

- r is the distance between the two point masses.

Bondi pointed out that a negative mass will fall toward (and not away from) "normal" matter, since although the gravitational force is repulsive, the negative mass (according to Newton's law, F=ma) responds by accelerating in the opposite of the direction of the force. Normal mass, on the other hand, will fall away from the negative matter. He noted that two identical masses, one positive and one negative, placed near each other will therefore self-accelerate in the direction of the line between them, with the negative mass chasing after the positive mass.[10] Notice that because the negative mass acquires negative kinetic energy, the total energy of the accelerating masses remains at zero. Forward pointed out that the self-acceleration effect is due to the negative inertial mass, and could be seen induced without the gravititational forces between the particles.[11]

The Standard Model of particle physics, which describes all presently known forms of matter, does not include negative mass. Although cosmological dark matter may consist of particles outside the Standard Model whose nature is unknown, their mass is ostensibly known - since they were postulated from their gravitational effects on surrounding objects, which implies their mass is positive. (The proposed cosmological dark energy, on the other hand, is more complicated, since according to general relativity the effects of both its energy density and its negative pressure contribute to its gravitational effect.)

Fifth force

Under general relativity any form of energy couples with spacetime to create the geometries that cause gravity. A longstanding question was whether or not these same equations applied to antimatter. The issue was considered solved in 1960 with the development of CPT symmetry, which demonstrated that antimatter follows the same laws of physics as "normal" matter, and therefore has positive energy content and also causes (and reacts to) gravity like normal matter.

For much of the later quarter of the 20th century, the physics community has been involved in an attempt to produce a unified field theory, a single physical theory that explains the four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces. Scientists have made progress in unifying the three quantum forces, but gravity has remained "the problem" in every attempt. This has not stopped any number of such attempts being made, however.

Generally these attempts tried to "quantize gravity" by positing a particle, the graviton, that carried gravity in the same way that photons (light) carry electromagnetism. Simple attempts along this direction all failed, however, leading to more complex examples that attempted to account for these problems. Two of these, supersymmetry and the relativity related supergravity, both required the existence of an extremely weak "fifth force" carried by a graviphoton, which coupled together several "loose ends" in quantum field theory, in an organized manner. As a side effect, both theories also all but required that antimatter be affected by this fifth force in a way similar to anti-gravity, dictating repulsion away from mass. Several experiments were carried out in the 1990s to measure this effect, but none yielded positive results.[12]

General-relativistic "warp drives"

There are solutions of the field equations of general relativity which describe "warp drives" (such as the famous Alcubierre metric) and stable, traversable wormholes. This by itself is not significant, since any spacetime geometry is a solution of the field equations for some configuration of the stress-energy tensor field (see exact solutions in general relativity). General relativity does not constrain the geometry of spacetime unless outside constraints are placed on the stress-energy tensor. Warp-drive and traversable-wormhole geometries are well-behaved in most areas, but require regions of exotic matter; thus they are excluded as solutions if the stress-energy tensor is limited to known forms of matter (including dark matter and dark energy).

Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program

During the close of the twentieth century NASA provided funding for the Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program (BPP) from 1996 through 2002. This program studied a number of "far out" designs for space propulsion that were not receiving funding through normal university or commercial channels. Anti-gravity-like concepts were investigated under the name "diametric drive". The work of the BPP program continues in the independent, non-NASA affiliated Tau Zero Foundation.

Empirical claims and commercial efforts

Anti-gravity devices are a common invention in the "alt" field, often requiring a completely new physics framework in order to work. Most of these devices rather obviously do not work, and are often parts of grander conspiracy theories. However there have also been a number of commercial attempts to build such devices as well, and a small number of reports of anti-gravity-like effects in the scientific literature. As of 2007, none of the examples that follow are accepted as genuine, reproducible examples of practically applicable anti-gravity, at least by the larger physics community.

Gyroscopic devices

Gyroscopes produce a force when twisted that operates "out of plane" and can appear to lift themselves against gravity. Although this force is well understood to be illusory, even under Newtonian models, it has nevertheless generated numerous claims of anti-gravity devices and any number of patented devices. None of these devices have ever been demonstrated to work under controlled conditions, and have often become the subject of conspiracy theories as a result. A famous example is that of Professor Eric Laithwaite of Imperial College, London, in the 1974 address to the Royal Institution.

Perhaps the best known example is a series of patents issued to Henry William Wallace, an engineer at GE Aerospace in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and GE Re-Entry Systems in Philadelphia. He constructed devices that rapidly spun disks of brass, a material made up largely of elements with a total half-integer nuclear spin.[13] He claimed that by rapidly rotating a disk of such material, the nuclear spin became aligned, and as a result created a "gravitomagnetic" field in a fashion similar to the magnetic field created by the Barnett effect.

Hayasaka and Takeuchi had reported weight decreases along the axis of a right spinning gyroscope.[14] Tests of their claims by Nitschke and Wilmath yielded null results.[15] A few years later, recommendations were made to conduct further tests.[16]

Provatidis and Tsiriggakis have proposed a novel gyroscope equipped by couples of rotating mass particles that draw only the upper (or lower) 180 degrees of a circle, thus producing net impulse per full revolution. This is achieved by transforming the previously used circular orbit into a figure-eight-shaped path (symbol of infinity) of variable curvature that entirely lies on the surface of a hemisphere.[17] Moreover, it was claimed that the spinning of the entire mechanism, in conjunction with the resonance of the centrifugal force through two servomotors, produces antigravity propulsion towards the axis of symmetry of the aforementioned hemisphere.[18]

Thomas Townsend Brown's gravitator

During the 1920s Thomas Townsend Brown, a high-voltage experimenter, produced a device he called the "gravitator" which he claimed used an unknown force to produce anti-gravity effects by applying high voltages to materials with high dielectric constants. Although it was claimed that the device operated outside of working mass, Brown abandoned this work and moved on to produce a series of successful high-voltage devices in the following years.

The Biefeld-Brown effect nevertheless lives on. A 1956 analysis by the Gravity Research Group and by a technical writer, under the pen name of Intel (1956), claimed the Biefeld-Brown effect was the primary theory tested by the aerospace firms in the 1950s, although it should be noted that "Intel" is an unreliable witness in this respect. It has remained a constant theme in the UFO field, and has recently been a topic of some discussion in this field under the name lifters. There appears to be a general understanding that the lifters require a working fluid, air specifically (ion wind), and that they do not demonstrate new physics.

Gravitoelectric coupling

The Russian researcher Eugene Podkletnov claims to have discovered experimenting with superconductors in 1995, that a fast rotating superconductor reduces the gravitational effect. Many studies have attempted to reproduce Podkletnov's experiment, always to no results.[19][20][21][22]

In 1989, Ning Li, of the University of Alabama in Huntsville theoretically demonstrated how a time dependent magnetic field could cause the spins of the lattice ions in a superconductor to generate detectable gravitomagnetic and gravitoelectric fields. In 1999, Li and her team appeared in Popular Mechanics, claiming to have constructed a working prototype to generate what she described as "AC Gravity." No further evidence of this prototype has been offered.[23]

Recent progression

The Institute for Gravity Research of the Göde Scientific Foundation has tried to reproduce different experiments which allegedly show an antigravity effect. All attempts to observe an antigravity effect have been unsuccessful. The foundation has offered a reward of one million euros[24] for a reproducible antigravity experiment.

Tajmar et al. (2006 & 2007 & 2008)

A paper by Martin Tajmar et al. in 2006 claims detection of an artificial gravitational field around a rotating superconductor, proportional to the angular acceleration of the superconductor.[25] A subsequent paper claims to explain the phenomenon in terms of the nonzero cosmological constant.[26]

In July 2007, Graham et al. of the Canterbury Ring Laser Group, New Zealand, reported results from an attempt to test the same effect with a larger rotating superconductor. They report no indication of any effect within the measurement accuracy of the experiment. Given the conditions of the experiment, the Canterbury group conclude that if any such 'Tajmar' effect exists, it is at least 22 times smaller than predicted by Tajmar in 2006.[27] However, the last sentence of their paper states: "Our experimental results do not have the sensitivity to either confirm or refute these recent results [from 2007]"[28].

Conventional effects that mimic anti-gravity effects

- Magnetic levitation suspends an object against gravity by use of electromagnetic forces. While visually impressive, gravitation itself functions normally in such devices. Various alleged anti-gravity devices may in reality work by electromagnetism.

- A tidal force causes objects to move along diverging paths near a massive body (such as a planet or star), producing effects that seem like repulsion or disruptive forces when observed locally. This is not anti-gravity. In Newtonian mechanics, the tidal force is the effect of the larger object's gravitational force being different at the differing locations of the diverging bodies. Equivalently, in Einsteinian gravity, the tidal force is the effect of the diverging bodies following different paths in the negatively curved spacetime around the larger body.

- Large amounts of normal matter can be used to produce a gravitational field that compensates for the effects of another gravitational field, though the entire assembly will still be attracted to the source of the larger field. Physicist Robert L. Forward proposed using lumps of degenerate matter to locally compensate for the tidal forces near a neutron star.

- Ionocraft, or sometimes referred to as "Lifters" have been claimed to defy gravity, but in fact they use accelerated ions which have been stripped from the air around them to produce thrust. The thrust produced by one of these toys is not enough to lift its own power supply. Specifically, a special type of electrohydrodynamic thruster uses the Biefeld–Brown effect to hover.

See also

- Gravitational interaction of antimatter

- Gravitational induction

- Artificial gravity

- Burkhard Heim

- Exotic matter

- Heim Theory

- Searl Effect Generator

- Hutchison effect

- Dean drive

- The spindizzy drive in the science fiction novels of James Blish

- Electrostatic levitation

- Magnetic levitation

- Casimir effect

- Apergy

- Viktor Grebennikov

- Clinostat

Coral Castle: The Mystey of Ed Leddskalnin and His American Stonehenge

References

- ↑ Peskin, M and Schroeder, D. ;An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory (Westview Press, 1995) [ISBN 0-201-50397-2]

- ↑ Wald, Robert M. (1984). General Relativity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-87033-2.

- ↑ Polchinski, Joseph (1998). String Theory, Cambridge University Press. A modern textbook

- ↑ Thompson, Clive (August 2003). "The Antigravity Underground". Wired. http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/11.08/pwr_antigravity.html. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ↑ "On the Verge of Antigravity". About.com. http://paranormal.about.com/library/weekly/aa081902a.htm. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ↑ Mooallem, J. (2007, October). A curious attraction. Harper's Magazine, 315(1889), pp. 84-91.

- ↑ Goldberg, J. M. (1992). US air force support of general relativity: 1956-1972. In, J. Eisenstaedt & A. J. Kox (Ed.), Studies in the History of General Relativity, Volume 3 Boston, Massachusetts: Center for Einstein Studies. ISBN 0-8176-3479-7

- ↑ Mallan, L. (1958). Space satellites (How to book 364). Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, pp. 9-10, 137, 139. LCCN 58-001060

- ↑ Clarke, A. C. (1957, December). The conquest of gravity, Holiday, 22(6), 62

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bondi, H. (1957, July). Negative mass in general relativity. Reviews of Modern Physics, 29(3), 423-428.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Forward, R. L. (1990, Jan.-Feb.), "Negative matter propulsion," Journal of Propulsion and Power, Vol. 6 (1), pp. 28-37; see also commentary Landis, G.A. (1991) "Comments on Negative Mass Propulsion," 'Journal of Propulsion and Power, Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 304.

- ↑ Supergravity and the Unification of the Laws of Physics, by Daniel Z. Freedman and Peter van Nieuwenhuizen, Scientific American, February 1978

- ↑ METHOD AND APPARATUS FOR GENERATING A SECONDARY GRAVITATIONAL FORCE FIELD

- ↑ Hayasaka, H. and Takeuchi, S. (1989). Phys. Rev. Lett., 63, 2701-2704

- ↑ Nitschke, J. M., and Wilmath, P. A. (1990). Phys. Rev. Lett., 64(18), 2115-2116

- ↑ Iwanaga, N. (1999). Reviews of some field propulsion methods from the general relativistic standpoint.AIP Conference Proceedings, 458, 1015-1059.

- ↑ Provatidis, Christopher, G. (2009). A novel mechanism to produce figure-eight-shaped closed curves in the three-dimensional space, 3rd International Conference on Experiments/Process/System Modeling/Simulation & Optimization (3rd IC-EpsMsO), Athens, 8-11 July

- ↑ Tsiriggakis, V. Th. and Provatidis C. G. (2008). Antigravity Mechanism, US Patent Application No.61/110,307 (Filing date: Oct. 31, 2008); also at http://www.tsiriggakis.gr/sm.html; also: Provatidis, C., and Tsiriggakis, V., A new concept and design aspects of an ‘antigravity’ propulsion mechanism based on inertial forces, Proceedings of 46th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Nashville, TN, 25-28 July 2010.

- ↑ Li, N., Noever, D., Robertson, T., Koczor, R., and Brantley, W., "Static Test for a Gravitational Force Coupled to Type II YBCO Superconductors," Physica C, 281, 260-267, (1997).

- ↑ Woods, C., Cooke, S., Helme, J., and Caldwell, C., "Gravity Modification by High Temperature Superconductors," Joint Propulsion Conference, AIAA 2001-3363, (2001).

- ↑ Hathaway, G., Cleveland, B., and Bao, Y., "Gravity Modification Experiment using a Rotating Superconducting Disc and Radio Frequency Fields," Physica C, 385, 488-500, (2003).

- ↑ Tajmar, M., and de Matos, C.J., "Gravitomagnetic Field of a Rotating Superconductor and of a Rotating Superfluid," Physica C, 385(4), 551-554, (2003).

- ↑ Taming Gravity - Popular Mechanics at www.popularmechanics.com

- ↑ Institute of Gravity Research - Antigravity at www.gravitation.org

- ↑ M. Tajmar, F. Plesescu, K. Marhold, C.J. de Matos: Experimental Detection of the Gravitomagnetic London Moment

- ↑ M. Tajmar, F. Plesescu, B. Seifert, K. Marhold: Measurement of Gravitomagnetic and Acceleration Fields Around Rotating Superconductors

- ↑ Graham, R.D.; Hurst, R.B.; Thirkettle, R.J.; Rowe, C.H.; Butler, P.H. (July 2007). "Experiment to Detect Frame Dragging in a Lead Superconductor". http://www.ringlaser.org.nz/papers/SuperFrameDragging2007.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-19. (Submitted to Physica C)

- ↑ M. Tajmar, F. Plesescu, B. Seifert, R. Schnitzer, I. Vasiljevich, Search for framedragging in the vicinity of spinning superconductors, in: proceedings of the 18th International Conference on General Relativity & Gravitation, Sydney, 2007.

- Cady, W. M. (1952, September 15). "Thomas Townsend Brown: Electro-Gravity Device" (File 24-185). Pasadena, CA: Office of Naval Research. Public access to the report was authorized on October 1, 1952.

- Li, N., & Torr, D. (1991). Physical Review, 43D, 457.

- Li, N., & Torr, D. (1992a). Physical Review, 46B, 5489.

- Li, N., & Torr, D. (1992b). Bulletin of the American Physical Society, 37, 441.

External links

- Responding to Mechanical Antigravity, a NASA paper debunking a wide variety of gyroscopic (and related) devices

- Göde Scientific Foundation