Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics to animal or non-living things, phenomena, material states and objects or abstract concepts. Examples include animals and plants and forces of nature such as winds, rain or the sun depicted as creatures with human motivations, and/or the abilities to reason and converse. The term derives from the combination of the Greek ἄνθρωπος (ánthrōpos), "human" and μορφή (morphē), "shape" or "form".

It is strongly associated with art and storytelling where it has ancient roots. Most cultures possess a long-standing fable tradition with anthropomorphised animals as characters that can stand as commonly recognised types of human behavior.

Contents |

Prehistory

From the beginnings of human behavioural modernity in the Upper Paleolithic, about 40,000 years ago, examples of zoomorphic (animal-shaped) works of art occur that may represent the earliest evidence we have of anthropomorphism. One of the oldest known is an ivory sculpture, the Lion man of the Hohlenstein Stadel, Germany, a human-shaped figurine with a lion's head, determined to be about 32,000 years old[1][2]

It is not possible to say what exactly these prehistoric artworks represent. A more recent example is The Sorcerer, an enigmatic cave painting from the Trois-Frères Cave, Ariège, France: the figure's significance is unknown, but it is usually interpreted as some kind of great spirit or master of the animals. In either case there is an element of anthropomorphism.

This anthropomorphic art has been linked by archaeologist Steven Mithen with the emergence of more systematic hunting practices in the Upper Paleolithic (Mithen 1998). He proposes that these are the product of a change in the architecture of the human mind, an increasing fluidity between the natural history and social intelligences, where anthropomorphism allowed hunters to empathetically identify with hunted animals and better predict their movements.[3]

In religion and mythology

In religion and mythology, anthropomorphism refers to the perception of a divine being or beings in human form, or the recognition of human qualities in these beings. Many mythologies are concerned with anthropomorphic deities who express human characteristics such as jealousy, hatred, or love. The Greek gods, such as Zeus and Apollo, were often depicted in human form exhibiting human traits. Anthropomorphism in this case is referred to as anthropotheism.[4]

Numerous sects throughout history have been called anthropomorphites attributing such things as hands and eyes to God, including a sect in Egypt in the 4th century, and a 10th-century sect, who literally interpreted Genesis 1:27: "So God created man in His own image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them."[5]

From the perspective of adherents to religions in which humans were created in the form of the divine, the phenomenon may be considered theomorphism, or the giving of divine qualities to humans.

Criticism

Some religions, scholars, and philosophers found objections to anthropomorphic deities. The Greek philosopher Xenophanes (570–480 BC) said that "the greatest god" resembles man "neither in form nor in mind."[6] Anthropomorphism of God is rejected by Judaism and Islam, which both believe that God is beyond human limits of physical comprehension. Judaism's rejection grew after the advent of Christianity until becoming codified in 13 principles of Jewish faith authored by Maimonides in the 12th Century.

Hindus do not reject the concept of God in the abstract unmanifested but note problems; Lord Krishna said in the Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 12, Verse 5, that it is much more difficult to focus on God as the unmanifested than God with form (i.e., using anthropomorphic icons (murtis), due to human beings having the need to perceive via the senses.[7]

In his book Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion, Stewart Elliott Guthrie theorizes that all religions are anthropomorphisms that originate due to the brain's tendency to detect the presence or vestiges of other humans in natural phenomena.[8]

In literature

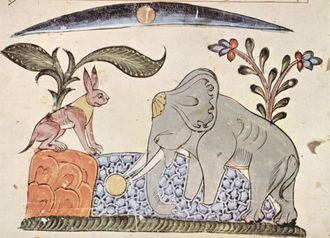

Fables

Anthropomorphism, sometimes referred to as personification, is a well established literary device from ancient times. It extends back to before Aesop's Fables[9] in 6th century BC Greece and the collections of linked fables from India, the Jataka Tales and Panchatantra, which employ anthropomorphised animals to illustrate principles of life. Many of the stereotypes of animals that are recognised today, such as the wiley fox and the proud lion, can be found in these collections. Aesop's anthropomorphisms were so familiar by the 1st century AD that they coloured the thinking of at least one philosopher:

And there is another charm about him, namely, that he puts animals in a pleasing light and makes them interesting to mankind. For after being brought up from childhood with these stories, and after being as it were nursed by them from babyhood, we acquire certain opinions of the several animals and think of some of them as royal animals, of others as silly, of others as witty, and others as innocent.

Apollonius noted that the fable was created to teach wisdom through fictions that are meant to be taken as fictions, contrasting them favourably with the poets' stories of the gods that are sometimes taken literally. Aesop, "by announcing a story which everyone knows not to be true, told the truth by the very fact that he did not claim to be relating real events."[10] The same consciousness of the fable as fiction is to be found in other examples across the world, one example being a traditional Ashanti way of beginning tales of the anthropomorphic trickster-spider Anansi: "We do not really mean, we do not really mean that what we are about to say is true. A story, a story; let it come, let it go."[11]

Fairy tales

Anthropomorphic motifs have been common in fairy tales from the earliest ancient examples set in a mythological context to the great collections of the Brothers Grimm and Perrault. The Tale of Two Brothers (Egypt, 13th century BC) features several talking cows and in Cupid and Psyche (Rome, 2nd century AD) Zephyrus, the west wind, carries Psyche away. Later an ant feels sorry for her and helps her in her quest.

Modern Literature

Building on the popularity of fables and fairy tales, specifically children's literature began to emerge in the 19th century with works such as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll, The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883) by Carlo Collodi and The Jungle Book (1894) by Rudyard Kipling, all employing anthropomorphic elements. This continued in the 20th century with many of the most popular titles having anthropomorphic characters,[12] examples being The Tales of Beatrix Potter (1901 onwards),[13] The Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis and Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) by A. A. Milne. In many of these stories the animals can be seen as representing facets of human personality and character.[14] As John Rowe Townsend remarks, discussing The Jungle Book in which the boy Mowgli must rely on his new friends the bear Baloo and the black panther Bagheera, "The world of the jungle is in fact both itself and our world as well."[14]

Consequently, this has led to a sub-culture known as Furry fandom, which promotes stories involving anthropomorphic animals and the examination and interpretation of humanity through anthropomorphism.[15]

The fantasy genre developed from mythological, fairy tale and Romance motifs[16] and characters, sometimes with anthropomorphic animals. The best-selling being The Hobbit[17] (1937) and The Lord of the Rings[18] (1954–1955), both by J. R. R. Tolkien.

In the 20th century too, the children's picture book market expanded massively.[19] Perhaps a majority of picture books have some kind of anthropomorphism,[12][20] with popular examples being The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969) by Eric Carle and The Gruffalo (1999) by Julia Donaldson.

In science

Need for objectivity

In the scientific community, using anthropomorphic language that suggests animals have intentions and emotions has been deprecated as indicating a lack of objectivity. Biologists have avoided the assumption that animals share some of the same mental, social, and emotional capacities of humans, relying instead on the strictly observable evidence.[21] Animals should be considered, as Ivan Pavlov wrote in 1927, "without any need to resort to fantastic speculations as to the existence of any possible subjective states."[22] More recently, The Oxford companion to animal behaviour (1987) advises "one is well advised to study the behaviour rather than attempting to get at any underlying emotion." [23]

Scientific method involves observations, definitions, and measurements of the subject of inquiry; empathy is not generally seen as a useful tool. While it is not unknown for scientists to lapse into anthropomorphism to make the objects of their study more humanly comprehensible or memorable, they often do it with an apology.[24][25]

Despite the impact of Charles Darwin's ideas in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (Konrad Lorenz in 1965 called him a "patron saint" of ethology)[26] ethology has generally focused on behaviour, not on emotion in animals.[26] Though in other ways Darwin was and is the epitome of science, his acceptance of anecdote and naive anthropomorphism stands out in sharp contrast to the lengths to which later scientists would go to overlook apparent mindedness, selfhood, individuality and agency:

| “ | Even insects play together, as has been described by that excellent observer, P. Huber, who saw ants chasing and pretending to bite each other, like so many puppies." | ” |

|

—Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man [27] |

||

Use of anthropomorphism

The study of great apes in their own environment has changed attitudes to anthropomorphism.[28] In the 1960s the three so-called "Leakey's Angels", Jane Goodall studying chimpanzees, Dian Fossey studying gorillas and Biruté Galdikas studying orangutangs, were all accused of "that worst of ethological sins - anthropomorphism"[29] Their descriptions of the great apes in the field have brought about a change in scientific ideas about anthropomorphism; it is now more widely accepted that empathy has an important part to play in research. As Frans de Waal writes: "To endow animals with human emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if we do not, we risk missing something fundamental, about both animals and us."[30] Alongside this has come increasing awareness of the linguistic abilities of the great apes and the recognition that they are tool-makers and have individuality and culture.

In Sports

Anthropomorphic animals are often used as mascots for sports teams or sporting events, often represented by humans in costumes.

See also

- Anthropic principle

- Anthropocentrism

- Furry Fandom

- Humanoid

- Kemono

- List of anthropomorphic personifications

- Moe anthropomorphism

- National personification

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Stereotypes of animals

- Talking animals in fiction

- Zoomorphism

- Aniconism: the contrast concept

Notes

- ↑ "Lionheaded Figurine". http://www.showcaves.com/english/explain/Archaeology/Loewenfrau.html. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ↑ Dalton, Rex (2004-01-01). "Lion Man Oldest Statue". VNN World. http://www.vnn.org/world/WD0401/WD01-8500.html. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ↑ Gardner, Howard (9 October 1997). "Thinking About Thinking". New York Review of Books. http://cogweb.ucla.edu/Abstracts/Gardner_on_Mithen.html. Retrieved 8 May 2010. "I find most convincing Mithen's claim that human intelligence lies in the capacity to make connections: through using metaphors"

- ↑ "anthropotheism". Ologies & -Isms. The Gale Group, Inc.. 2008. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Anthropotheism. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ↑

This article incorporates content from the 1728 Cyclopaedia, a publication in the public domain. Anthropomorphite.

This article incorporates content from the 1728 Cyclopaedia, a publication in the public domain. Anthropomorphite. - ↑ Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies V xiv 109.1–3

- ↑ Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, by Jeanne Fowler, pgs. 42-43, at Books.Google.com and Flipside of Hindu symbolism, by M. K. V. Narayan at pgs. 84-85 at Books.Google.com

- ↑ Guthrie, Stewart (1995). Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0195098919. http://books.google.com/books?id=dZNAQh6TuwIC&dq=Faces+in+the+Clouds:+A+New+Theory+of+Religion&printsec=frontcover&source=bn&hl=en&ei=zkIxSvGuJ6GqtgeLlYzrBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4#PPA7,M1.

- ↑ The Hawk and the Nightingale, recorded by Hesiod in his Works and Days is regarded by some as the earliest fable attributable to a literary work. See for instance Britanica. 1910. pp. 410.: "The poem also contains the earliest known fable in Greek literature"

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Philostratus, Flavius (c.210 AD). The Life of Apollonius, 5.14. Translated by F.C. Conybeare. the Loeb Classical Library (1912)

- ↑ Kwesi Yankah (1983) (PDF). The Akan Trickster Cycle: Myth or Folktale?. Trinidad University of the West Indes. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/2022/125/1/Akan_Yankah.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The top 50 children's books". The Telegraph. 22 Feb 2008. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1579457/The-top-50-childrens-books.html. Retrieved May 12, 2010. and Sophie Borland (22 Feb 2008). "Narnia triumphs over Harry Potter". The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1579456/Narnia-triumphs-over-Harry-Potter.html. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Beatrix Potter". Victoria and Albert Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/prints_books/features/potter/index.html. Retrieved 2 May 2010.: "Beatrix Potter is still one of the world's best-selling and best-loved children's authors. Potter wrote and illustrated a total of 28 books, including the 23 Tales, the 'little books' that have been translated into more than 35 languages and sold over 100 million copies."

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Gamble, Nikki; Yates, Sally (2008). Exploring Children's Literatur. Sage Publications Ltd;. pp. 224. ISBN 978-1412930130. http://books.google.com/books?id=pMRQiO4mIzQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Exploring+Children%27s+Literature&ei=HJwGTLzJNIu-ygSKzNnQBw&cd=1#v=snippet&q=Page%2089&f=false.

- ↑ Patten, Fred (2006). Furry! The World's Best Anthropomorphic Fiction. ibooks. pp. 427–436. ISBN 1-59687-319-1.

- ↑ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, p 621, ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ↑ 100 million copies sold: BBC: Tolkien's memorabilia go on sale. 18 March 2008

- ↑ 150 million sold, a 2007 estimate of copies of the full story sold, whether published as one volume, three, or some other configuration.The Toronto Star 16 April 2007

- ↑ It is estimated that the UK market for children's books was worth GBP 672m in 2004. The Value of the Children's Picture Book Market...

- ↑ Ben Myers (10 June 2008). "Why we're all animal lovers". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/booksblog/2008/jun/10/whywereallanimallovers. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ↑ Introduction to Flynn, Cliff (2008). Social Creatures: A Human and Animal Studies Reader. Lantern Books. http://www.anthropress.org/excerpt.html?session=51678f1a4141f8aadcf5fd7898cdc296&cat=&id=9781590561232&expid=534.

- ↑ Ryder, Richard. Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes Towards Speciesism. Berg, 2000, p. 6.

- ↑ Masson and McCarthy 1996, xviii

- ↑ For example: "The larval insect is, if I may be permitted to lapse for a moment into anthropomorphism, a sluggish, greedy, self-centred creature, while the adult is industrious, abstemious and highly altruistic..." Wheeler, William Morton (November 1911). "Insect parasitism and its peculiarities". Popular Science. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=0yEDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA431&dq=ethology+anthropomorphism&lr=&as_drrb_is=b&as_minm_is=1&as_miny_is=1800&as_maxm_is=1&as_maxy_is=1960&as_brr=3&ei=5hPfS7OjCofIyASmprzhCQ&cd=2#v=onepage&q=anthropomorphism&f=false.

- ↑ "When the accurate and proper use of language has entrapped a zoologist into a statement that seems to him heretical, it is quite usual to hear him apologise for speaking teleologically and he generally looks as sheepish and embarrassed about it as if his bedroom had been found full of empty whisky bottles." R.J. Pumphrey quoted in In Praise of Anthropomorphism by C. W. Hume, January 1959

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Black, J (Jun 2002). "Darwin in the world of emotions" (Free full text). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 95 (6): 311–3. doi:10.1258/jrsm.95.6.311. ISSN 0141-0768. PMID 12042386. PMC 1279921. http://www.jrsm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12042386.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1st ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 0-8014-2085-7. http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/Freeman_TheDescentofMan.html. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ Also in captivity: "A thoroughgoing attempt to avoid anthropomorphic description in the study of temperament was made over a two-year period at the Yerkes laboratories. All that resulted was an almost endless series of specific acts in which no order or meaning could be found. On the other hand, by the use of frankly anthropomorphic concepts of emotion and attitude one could quickly and easily describe the peculiarities of individual animals... Whatever the anthropomorphic terminology may seem to imply about conscious states in chimpanzee, it provides an intelligible and practical guide to behavior." Hebb, Donald O. (1946). "Emotion in man and animal: An analysis of the intuitive processes of recognition.". Psychological Review 53: 88–106.

- ↑ cited in Masson and McCarthy 1996, p9 Google books

- ↑ Frans de Waal (1997-07). "Are We in Anthropodenial?". Discover. pp. 50–53.

References

- Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff; Susan McCarthy (1996). When Elephants Weep: Emotional Lives of Animals. Vintage. pp. 272. ISBN 8-0099478911.

- Mithen, Steven (1998). The Prehistory Of The Mind: A Search for the Origins of Art, Religion and Science. Phoenix. pp. 480. ISBN 978-0753802045.