Anemia

| Anemia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

The pale hand of a woman with severe anemia (right) in comparison to the normal hand of her husband (left). |

|

| ICD-10 | D50.-D64. |

| ICD-9 | 280-285 |

| DiseasesDB | 663 |

| MedlinePlus | 000560 |

| eMedicine | med/132 emerg/808 emerg/734 |

| MeSH | D000740 |

Anemia (pronounced /əˈniːmiə/, also spelled anaemia and anæmia; from Ancient Greek ἀναιμία anaimia, meaning lack of blood) is a decrease in normal number of red blood cells (RBCs) or less than the normal quantity of hemoglobin in the blood.[1][2] However, it can include decreased oxygen-binding ability of each hemoglobin molecule due to deformity or lack in numerical development as in some other types of hemoglobin deficiency.

Because hemoglobin (found inside RBCs) normally carries oxygen from the lungs to the tissues, anemia leads to hypoxia (lack of oxygen) in organs. Because all human cells depend on oxygen for survival, varying degrees of anemia can have a wide range of clinical consequences.

Anemia is the most common disorder of the blood. There are several kinds of anemia, produced by a variety of underlying causes. Anemia can be classified in a variety of ways, based on the morphology of RBCs, underlying etiologic mechanisms, and discernible clinical spectra, to mention a few. The three main classes of anemia include excessive blood loss (acutely such as a hemorrhage or chronically through low-volume loss), excessive blood cell destruction (hemolysis) or deficient red blood cell production (ineffective hematopoiesis).

There are two major approaches: the "kinetic" approach which involves evaluating production, destruction and loss,[3] and the "morphologic" approach which groups anemia by red blood cell size. The morphologic approach uses a quickly available and cheap lab test as its starting point (the MCV). On the other hand, focusing early on the question of production may allow the clinician to more rapidly expose cases where multiple causes of anemia coexist.

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

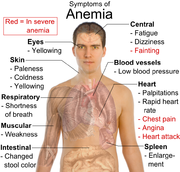

Anemia goes undetermined in many people, and symptoms can be minor or vague. The signs and symptoms can be related to the anemia itself, or the underlying cause.

Most commonly, people with anemia report non-specific symptoms of a feeling of weakness, or fatigue, general malaise and sometimes poor concentration. They may also report shortness of breath, dyspnea, on exertion. In very severe anemia, the body may compensate for the lack of oxygen carrying capability of the blood by increasing cardiac output. The patient may have symptoms related to this, such as palpitations, angina (if preexisting heart disease is present), intermittent claudication of the legs, and symptoms of heart failure.

On examination, the signs exhibited may include pallor (pale skin, mucosal linings and nail beds) but this is not a reliable sign. There may be signs of specific causes of anemia, e.g., koilonychia (in iron deficiency), jaundice (when anemia results from abnormal break down of red blood cells — in hemolytic anemia), bone deformities (found in thalassaemia major) or leg ulcers (seen in sickle cell disease).

In severe anemia, there may be signs of a hyperdynamic circulation: a fast heart rate (tachycardia), flow murmurs, and cardiac enlargement. There may be signs of heart failure.

Pica, the consumption of non-food based items such as dirt, paper, wax, grass, ice, and hair, may be a symptom of iron deficiency, although it occurs often in those who have normal levels of hemoglobin.

Chronic anemia may result in behavioral disturbances in children as a direct result of impaired neurological development in infants, and reduced scholastic performance in children of school age.

Restless legs syndrome is more common in those with iron deficiency anemia.

Less common symptoms may include swelling of the legs or arms, chronic heartburn, vague bruises, vomiting, increased sweating, and blood in stool.

Diagnosis

Generally, clinicians request complete blood counts in the first batch of blood tests in the diagnosis of an anemia. Apart from reporting the number of red blood cells and the hemoglobin level, the automatic counters also measure the size of the red blood cells by flow cytometry, which is an important tool in distinguishing between the causes of anemia. Examination of a stained blood smear using a microscope can also be helpful, and is sometimes a necessity in regions of the world where automated analysis is less accessible.

In modern counters, four parameters (RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, MCV and RDW) are measured, allowing others (hematocrit, MCH and MCHC) to be calculated, and compared to values adjusted for age and sex. Some counters estimate hematocrit from direct measurements.

| Age or gender group | Hb threshold (g/dl) | Hb threshold (mmol/l) |

|---|---|---|

| Children (0.5–5.0 yrs) | 11.0 | 6.8 |

| Children (5–12 yrs) | 11.5 | 7.1 |

| Teens (12–15 yrs) | 12.0 | 7.4 |

| Women, non-pregnant (>15yrs) | 12.0 | 7.4 |

| Women, pregnant | 11.0 | 6.8 |

| Men (>15yrs) | 13.0 | 8.1 |

Reticulocyte counts, and the "kinetic" approach to anemia, have become more common than in the past in the large medical centers of the United States and some other wealthy nations, in part because some automatic counters now have the capacity to include reticulocyte counts. A reticulocyte count is a quantitative measure of the bone marrow's production of new red blood cells. The reticulocyte production index is a calculation of the ratio between the level of anemia and the extent to which the reticulocyte count has risen in response. If the degree of anemia is significant, even a "normal" reticulocyte count actually may reflect an inadequate response.

If an automated count is not available, a reticulocyte count can be done manually following special staining of the blood film. In manual examination, activity of the bone marrow can also be gauged qualitatively by subtle changes in the numbers and the morphology of young RBCs by examination under a microscope. Newly formed RBCs are usually slightly larger than older RBCs and show polychromasia. Even where the source of blood loss is obvious, evaluation of erythropoiesis can help assess whether the bone marrow will be able to compensate for the loss, and at what rate.

When the cause is not obvious, clinicians use other tests: ESR, ferritin, serum iron, transferrin, RBC folate level, serum vitamin B12, hemoglobin electrophoresis, renal function tests (e.g. serum creatinine).

When the diagnosis remains difficult, a bone marrow examination allows direct examination of the precursors to red cells.

Classification

Production vs. destruction or loss

The "kinetic" approach to anemia yields what many argue is the most clinically relevant classification of anemia. This classification depends on evaluation of several hematological parameters, particularly the blood reticulocyte (precursor of mature RBCs) count. This then yields the classification of defects by decreased RBC production versus increased RBC destruction and/or loss. Clinical signs of loss or destruction include abnormal peripheral blood smear with signs of hemolysis; elevated LDH suggesting cell destruction; or clinical signs of bleeding, such as guiaic-positive stool, radiographic findings, or frank bleeding.

The following is a simplified schematic of this approach:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reticulocyte production index shows inadequate production response to anemia. |

|

|

|

Reticulocyte production index shows appropriate response to anemia = ongoing hemolysis or blood loss without RBC production problem. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

No clinical findings consistent with hemolysis or blood loss: pure disorder of production. |

|

Clinical findings and abnormal MCV: hemolysis or loss and chronic disorder of production*. |

|

Clinical findings and normal MCV= acute hemolysis or loss without adequate time for bone marrow production to compensate**. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Macrocytic anemia (MCV>100) |

|

Normocytic anemia (80<MCV<100) |

|

|

Microcytic anemia (MCV<80) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

* For instance, sickle cell anemia with superimposed iron deficiency; chronic gastric bleeding with B12 and folate deficiency; and other instances of anemia with more than one cause.

** Confirm by repeating reticulocyte count: ongoing combination of low reticulocyte production index, normal MCV and hemolysis or loss may be seen in bone marrow failure or anemia of chronic disease, with superimposed or related hemolysis or blood loss.

Red blood cell size

In the morphological approach, anemia is classified by the size of red blood cells; this is either done automatically or on microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear. The size is reflected in the mean corpuscular volume (MCV). If the cells are smaller than normal (under 80 fl), the anemia is said to be microcytic; if they are normal size (80–100 fl), normocytic; and if they are larger than normal (over 100 fl), the anemia is classified as macrocytic. This scheme quickly exposes some of the most common causes of anemia; for instance, a microcytic anemia is often the result of iron deficiency. In clinical workup, the MCV will be one of the first pieces of information available; so even among clinicians who consider the "kinetic" approach more useful philosophically, morphology will remain an important element of classification and diagnosis.

Here is a schematic representation of how to consider anemia with MCV as the starting point:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Macrocytic anemia (MCV>100) |

|

|

|

|

|

Normocytic anemia (MCV 80–100) |

|

|

|

|

|

Microcytic anemia (MCV<80) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

High reticulocyte count |

|

|

|

|

|

Low reticulocyte count |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other characteristics visible on the peripheral smear may provide valuable clues about a more specific diagnosis; for example, abnormal white blood cells may point to a cause in the bone marrow.

Microcytic anemia

Microcytic anemia is primarily a result of hemoglobin synthesis failure/insufficiency, which could be caused by several etiologies:

- Heme synthesis defect

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Anemia of chronic disease (more commonly presenting as normocytic anemia)

- Globin synthesis defect

- alpha-, and beta-thalassemia

- HbE syndrome

- HbC syndrome

- and various other unstable hemoglobin diseases

- Sideroblastic defect

- Hereditary sideroblastic anemia

- Acquired sideroblastic anemia, including lead toxicity

- Reversible sideroblastic anemia

Iron deficiency anemia is the most common type of anemia overall and it has many causes. RBCs often appear hypochromic (paler than usual) and microcytic (smaller than usual) when viewed with a microscope.

- Iron deficiency anemia is caused by insufficient dietary intake or absorption of iron to replace losses from menstruation or losses due to diseases.[6] Iron is an essential part of hemoglobin, and low iron levels result in decreased incorporation of hemoglobin into red blood cells. In the United States, 20% of all women of childbearing age have iron deficiency anemia, compared with only 2% of adult men. The principal cause of iron deficiency anemia in premenopausal women is blood lost during menses. Studies have shown that iron deficiency without anemia causes poor school performance and lower IQ in teenage girls. Iron deficiency is the most prevalent deficiency state on a worldwide basis. Iron deficiency is sometimes the cause of abnormal fissuring of the angular (corner) sections of the lips (angular stomatitis).

- Iron deficiency anemia can also be due to bleeding lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Faecal occult blood testing, upper endoscopy and lower endoscopy should be performed to identify bleeding lesions. In men and post-menopausal women the chances are higher that bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract could be due to colon polyp or colorectal cancer.

- Worldwide, the most common cause of iron deficiency anemia is parasitic infestation (hookworm, amebiasis, schistosomiasis and whipworm).[7]

Macrocytic anemia

- Megaloblastic anemia, the most common cause of macrocytic anemia, is due to a deficiency of either vitamin B12, folic acid (or both). Deficiency in folate and/or vitamin B12 can be due either to inadequate intake or insufficient absorption. Folate deficiency normally does not produce neurological symptoms, while B12 deficiency does.

- Pernicious anemia is caused by a lack of intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor is required to absorb vitamin B12 from food. A lack of intrinsic factor may arise from an autoimmune condition targeting the parietal cells (atrophic gastritis) that produce intrinsic factor or against intrinsic factor itself. These lead to poor absorption of vitamin B12.

- Macrocytic anemia can also be caused by removal of the functional portion of the stomach, such as during gastric bypass surgery, leading to reduced vitamin B12/folate absorption. Therefore one must always be aware of anemia following this procedure.

- Hypothyroidism

- Alcoholism commonly causes a macrocytosis, although not specifically anemia. Other types of Liver Disease can also cause macrocytosis.

- Methotrexate, zidovudine, and other drugs that inhibit DNA replication.

Macrocytic anemia can be further divided into "megaloblastic anemia" or "non-megaloblastic macrocytic anemia". The cause of megaloblastic anemia is primarily a failure of DNA synthesis with preserved RNA synthesis, which result in restricted cell division of the progenitor cells. The megaloblastic anemias often present with neutrophil hypersegmentation (6–10 lobes). The non-megaloblastic macrocytic anemias have different etiologies (i.e. there is unimpaired DNA globin synthesis,) which occur, for example in alcoholism.

In addition to the non-specific symptoms of anemia, specific features of vitamin B12 deficiency include peripheral neuropathy and subacute combined degeneration of the cord with resulting balance difficulties from posterior column spinal cord pathology.[8] Other features may include a smooth, red tongue and glossitis.

The treatment for vitamin B12-deficient anemia was first devised by William Murphy who bled dogs to make them anemic and then fed them various substances to see what (if anything) would make them healthy again. He discovered that ingesting large amounts of liver seemed to cure the disease. George Minot and George Whipple then set about to chemically isolate the curative substance and ultimately were able to isolate the vitamin B12 from the liver. All three shared the 1934 Nobel Prize in Medicine.[9]

Normocytic anemia

Normocytic anemia occurs when the overall hemoglobin levels are always decreased, but the red blood cell size (Mean corpuscular volume) remains normal. Causes include:

- Acute blood loss

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Aplastic anemia (bone marrow failure)

- Hemolytic anemia

Dimorphic anemia

When two causes of anemia act simultaneously, e.g., macrocytic hypochromic, due to hookworm infestation leading to deficiency of both iron and vitamin B12 or folic acid [10] or following a blood transfusion more than one abnormality of red cell indices may be seen. Evidence for multiple causes appears with an elevated RBC distribution width (RDW), which suggests a wider-than-normal range of red cell sizes.

Heinz body anemia

Heinz bodies form in the cytoplasm of RBCs and appear like small dark dots under the microscope. There are many causes of Heinz body anemia, and some forms can be drug induced. It is triggered in cats by eating onions[11] or acetaminophen (paracetamol). It can be triggered in dogs by ingesting onions or zinc, and in horses by ingesting dry red maple leaves.

Causes

Broadly, causes of anemia may be classified as impaired red blood cell (RBC) production, increased RBC destruction (hemolytic anemias), blood loss and fluid overload (hypervolemia). Several of these may interplay to eventually cause anemia. Indeed, the most common cause of anemia is blood loss, but this usually doesn't cause any lasting symptoms unless a relatively impaired RBC production develops because of iron deficiency.[12]

Impaired RBC production

- Disturbance of proliferation and differentiation of stem cells.

- Pure red cell aplasia[13]

- Aplastic anemia,[13] affecting all kinds of blood cells. Fanconi anemia is a hereditary disorder or defect featuring aplastic anemia and various other abnormalities.

- Anemia of renal failure,[13] by insufficient erythropoietin production

- Anemia of endocrine disorders

- Disturbance of proliferation and maturation of erythroblasts

- Pernicious anemia[13] is a form of megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency dependent on impaired absorption of vitamin B12.

- Anemia of folic acid deficiency.[13] As with vitamin B12, it causes megaloblastic anemia

- Anemia of prematurity, by diminished erythropoietin response to declining hematocrit levels, combined with blood loss from laboratory testing. It generally occurs in premature infants at 2 to 6 weeks of age.

- iron deficiency, resulting in deficient heme synthesis[13]

- thalassemias, causing deficient globin synthesis[13]

- Anemia of renal failure[13] (also causing stem cell dysfunction)

- Other mechanisms of impaired RBC production

- Myelophthisic anemia[13] or Myelophthisis is a severe type of anemia resulting from the replacement of bone marrow by other materials, such as malignant tumors or granulomas.

- Myelodysplastic syndrome[13]

- anemia of chronic inflammation[13]

Increased RBC destruction

Anemias of increased red blood cell destruction are generally classified as hemolytic anemias. These are generally featuring jaundice and elevated LDH levels.

- Intrinsic (intracorpuscular) abnormalities,[13] where there the red blood cells have defects that cause premature destruction. All of these, except paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, are hereditary genetic disorders.[14]

- Hereditary spherocytosis[13] is a hereditary defect that results in defects in the RBC cell membrane, causing the erythrocytes to be sequestered and destroyed by the spleen.

- Hereditary elliptocytosis,[13] another defect in membrane skeleton proteins

- Abetalipoproteinemia,[13] causing defects in membrane lipids

- Enzyme deficiencies

- Pyruvate kinase and hexokinase deficiencies,[13] causing defect glycolysis

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and glutathione synthetase deficiency,[13] causing increased oxidative stress

- Hemoglobinopathies

- Sickle cell anemia[13]

- Hemoglobinopathies causing unstable hemoglobins[13]

- paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria[13]

- Extrinsic (extracorpuscular) abnormalities

- Antibody-mediated

- Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia is an anemia caused by autoimmune attack against red blood cells, primarily by IgG. It is the most common of the autoimmune hemolytic diseases.[15] It can be idiopathic, that is, without any known cause, drug-associated or secondary to another disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus, or a malignancy, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)[16][16]

- Cold agglutinin hemolytic anemia is primarily mediated by IgM. It can be idiopathic[17] or result from an underlying condition.

- Rh disease,[13] one of the causes of hemolytic disease of the newborn

- Transfusion reaction to blood transfusions[13]

- Mechanical trauma to red cells

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemias, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation[13]

- Infections, including malaria[13]

- heart surgery

- Antibody-mediated

Blood loss

- Anemia of prematurity from frequent blood sampling for laboratory testing, combined with insufficient RBC production.

- Trauma[13] or surgery, causing acute blood loss

- Gastrointestinal tract lesions,[13] causing a rather chronic blood loss

- Gynecologic disturbances,[13] also generally causing chronic blood loss

Fluid overload

Fluid overload (hypervolemia) causes decreased hemoglobin concentration and apparent anemia:

- General causes of hypervolemia include excessive sodium or fluid intake, sodium or water retention and fluid shift into the intravascular space.[18]

- Anemia of pregnancy is anemia that is induced by blood volume expansion experienced in pregnancy.

Treatments

There are many different treatments for anemia and they depend on severity and cause.

Iron deficiency from nutritional causes is rare in non-menstruating adults (men and post-menopausal women). The diagnosis of iron deficiency mandates a search for potential sources of loss such as gastrointestinal bleeding from ulcers or colon cancer. Mild to moderate iron deficiency anemia is treated by oral iron supplementation with ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, or ferrous gluconate. When taking iron supplements, it is very common to experience stomach upset and/or darkening of the feces. The stomach upset can be alleviated by taking the iron with food; however, this decreases the amount of iron absorbed. Vitamin C aids in the body's ability to absorb iron, so taking oral iron supplements with orange juice is of benefit.

Vitamin supplements given orally (folic acid) or subcutaneously (vitamin B-12) will replace specific deficiencies.

In anemia of chronic disease, anemia associated with chemotherapy, or anemia associated with renal disease, some clinicians prescribe recombinant erythropoietin, epoetin alfa, to stimulate red cell production.

In severe cases of anemia, or with ongoing blood loss, a blood transfusion may be necessary.

Blood transfusions

Doctors attempt to avoid blood transfusion in general, since multiple lines of evidence point to increased adverse patient clinical outcomes with more intensive transfusion strategies. The physiological principle that reduction of oxygen delivery associated with anemia leads to adverse clinical outcomes is balanced by the finding that transfusion does not necessarily mitigate these adverse clinical outcomes.

In severe, acute bleeding, transfusions of donated blood are often lifesaving. Improvements in battlefield casualty survival is attributable, at least in part, to the recent improvements in blood banking and transfusion techniques.

Transfusion of the stable but anemic hospitalized patient has been the subject of numerous clinical trials, and transfusion is emerging as a deleterious intervention.

Four randomized controlled clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate aggressive versus conservative transfusion strategies in critically-ill patients. All four of these studies failed to find a benefit with more aggressive transfusion strategies.[19][20][21][22]

In addition, at least two retrospective studies have shown increases in adverse clinical outcomes with more aggressive transfusion strategies.[23][24]

Hyperbaric oxygen

Treatment of exceptional blood loss (anemia) is recognized as an indication for hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) by the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society.[25][26] The use of HBO is indicated when oxygen delivery to tissue is not sufficient in patients who cannot be transfused for medical or religious reasons. HBO may be used for medical reasons when threat of blood product incompatibility or concern for transmissible disease are factors.[25] The beliefs of some religions (ex: Jehovah's Witnesses) may prohibit the receipt of transfused blood products.[25]

In 2002, Van Meter reviewed the publications surrounding the use of HBO in severe anemia and found that all publications report a positive result.[27]

See also

- Human iron metabolism

- List of circulatory system conditions

References

- ↑ MedicineNet.com --> Definition of Anemia Last Editorial Review: 12/9/2000 8:31:00 AM

- ↑ merriam-webster dictionary --> anemia Retrieved on May 25, 2009

- ↑ "eMedicine – Anemia, Chronic : Article by Fredrick M Abrahamian, DO, FACEP". Emedicine.com. 2009-12-07. http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic734.htm#section~clinical. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ eMedicineHealth > anemia article Author: Saimak T. Nabili, MD, MPH. Editor: Melissa Conrad Stöppler, MD. Last Editorial Review: 12/9/2008. Retrieved on 4 April 2009

- ↑ World Health Organization (2008). Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241596657. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596657_eng.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ↑ Recommendations to Prevent and Control Iron Deficiency in the United States MMWR 1998;47 (No. RR-3) p. 5

- ↑ "Iron Deficiency Anaemia: Assessment, Prevention, and Control: A guide for programme managers" (PDF). http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/en/ida_assessment_prevention_control.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ eMedicine – Vitamin B-12 Associated Neurological Diseases : Article by Niranjan N Singh, MD, DM, DNB July 18, 2006

- ↑ "Physiology or Medicine 1934 – Presentation Speech". Nobelprize.org. 1934-12-10. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1934/press.html. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ "Dorlands Medical Dictionary". Mercksource.com. http://www.mercksource.com/pp/us/cns/cns_hl_dorlands.jspzQzpgzEzzSzppdocszSzuszSzcommonzSzdorlandszSzdorlandzSzdmd_a_37zPzhtm. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ "Onions are Toxic to Cats". Peteducation.com. http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?cls=0&cat=1763&articleid=1108. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ National Heart Lung and Blood Institute > What Causes Anemia? Retrieved on June 9, 2010

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 13.22 13.23 13.24 13.25 13.26 Table 12-1 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

- ↑ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; & Mitchell, Richard N. (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. p. 432 ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1

- ↑ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 637. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 AUTOIMMUNE HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA (AIHA) By J.L. Jenkins. The Regional Cancer Center. 2001

- ↑ Berentsen S, Beiske K, Tjønnfjord GE (October 2007). "Primary chronic cold agglutinin disease: an update on pathogenesis, clinical features and therapy". Hematology 12 (5): 361–70. doi:10.1080/10245330701445392. PMID 17891600. PMC 2409172. http://www.informaworld.com/openurl?genre=article&doi=10.1080/10245330701445392&magic=pubmed||1B69BA326FFE69C3F0A8F227DF8201D0.

- ↑ Page 62 (Fluid imbalances) in: Portable Fluids and Electrolytes (Portable Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. ISBN 1-58255-678-4.

- ↑ Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. (1999). "A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 340 (6): 409–17. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. PMID 9971864.

- ↑ Bush RL, Pevec WC, Holcroft JW (1997). "A prospective, randomized trial limiting perioperative red blood cell transfusions in vascular patients". Am. J. Surg. 174 (2): 143–8. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00073-1. PMID 9293831.

- ↑ Bracey AW, Radovancevic R, Riggs SA, et al. (1999). "Lowering the hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in coronary artery bypass procedures: effect on patient outcome". Transfusion 39 (10): 1070–7. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39101070.x. PMID 10532600.

- ↑ McIntyre LA, Fergusson DA, Hutchison JS, et al. (2006). "Effect of a liberal versus restrictive transfusion strategy on mortality in patients with moderate to severe head injury". Neurocritical care 5 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1385/NCC:5:1:4. PMID 16960287.

- ↑ Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Pearl RG, et al. (2004). "The CRIT Study: Anemia and blood transfusion in the critically ill—current clinical practice in the United States". Crit. Care Med. 32 (1): 39–52. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000104112.34142.79. PMID 14707558.

- ↑ ABC (Anemia and Blood Transfusion in Critical Care) Investigators (2002). "Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients". JAMA 288 (12): 1499–507. doi:10.1001/jama.288.12.1499. PMID 12243637.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. "Exceptional Blood Loss — Anemia". http://www.uhms.org/ResourceLibrary/Indications/ExceptionalBloodLossAnemia/tabid/277/Default.aspx. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ Hart GB, Lennon PA, Strauss MB. (1987). "Hyperbaric oxygen in exceptional acute blood-loss anemia". J. Hyperbaric Med 2 (4): 205–210. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4352. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ Van Meter KW (2005). "A systematic review of the application of hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of severe anemia: an evidence-based approach". Undersea Hyperb Med 32 (1): 61–83. PMID 15796315. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4038. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||