Amoeba (genus)

| Amoeba | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Amoebozoa |

| Phylum: | Rhizopoda |

| Order: | Tubulinida |

| Family: | Amoebidae |

| Genus: | Amoeba Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1822 |

| Species | |

|

Amoeba proteus |

|

Amoeba (sometimes amœba or ameba, plural amoebae) is a genus of protozoan.[1]

Contents |

Terminology

There are many closely related terms that can be the source of confusion:

- Amoeba is a genus that includes species such as Amoeba proteus

- Amoebidae is a family that includes the Amoeba genus, among others.

- Amoebozoa is a kingdom that includes the Amoebidae family, among others.

- Amoeboids are organisms that move by crawling. Many (but not all) Amoeboids are Amoebozoa.

History

The amoeba was first discovered by August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof in 1757.[2] Early naturalists referred to Amoeba as the Proteus animalcule after the Greek god Proteus who could change his shape. The name "amibe" was given to it by Bory de Saint-Vincent,[3] from the Greek amoibè (αμοιβή), meaning change.[4]Dientamoeba fragili was first described in 1918, and was linked to harm in humans. [5]

Anatomy

.svg.png)

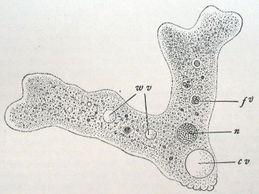

The cell's organelles and cytoplasm are enclosed by a cell membrane, obtaining its food through phagocytosis. Amoebae have a single large tubular pseudopod at the anterior end, and several secondary ones branching to the sides. The most famous species, Amoeba proteus, averages about 220-740 μm in length while moving,[6] making it a giant among amoeboids.[7] A few amoeboids belonging to different genera can grow larger, however, such as Gromia, Pelomyxa, and Chaos.

Amoebae's most recognizable features include one or more nuclei and a simple contractile vacuole to maintain osmotic equilibrium. Food enveloped by the amoeba is stored and digested in vacuoles. Amoebae, like other single-celled eukaryotic organisms, reproduce asexually via mitosis and cytokinesis, not to be confused with binary fission, which is how prokaryotes (bacteria) reproduce. In cases where the amoeba are forcibly divided, the portion that retains the nucleus will survive and form a new cell and cytoplasm, while the other portion dies. Amoebae also have no definite shape.[8]

Genome

The amoeba is remarkable for its very large genome. The species Amoeba protea has 290 billion (10^9) base pairs in its genome, while the related Polychaos dubium (formerly known as Amoeba dubia) has 670 billion base pairs. The human genome is small by contrast, with its count of 2.9 billion base pairs.[9]

Reaction to stimuli

Hypertonic and hypotonic solutions

Like most cells, amoebae are adversely affected by excessive osmotic pressure caused by extremely saline or dilute water. Amoebae will prevent the influx of salt in saline water, resulting in a net loss of water as the cell becomes isotonic with the environment, causing the cell to shrink. Placed into fresh water, amoebae will also attempt to match the concentration of the surrounding water, causing the cell to swell and sometimes burst.[10]

Amoebic cysts

In environments which are potentially lethal to the cell, an amoeba may become dormant by forming itself into a ball and secreting a protective membrane to become a microbial cyst. The cell remains in this state until it encounters more favourable conditions.[8] While in cyst form the amoeba will not replicate and may die if unable to emerge for a lengthy period of time.

Marine amoeba

Marine amoeba lack contractile vacuoles and their enzymes and organelles are not damaged by the salt water found in seas, oceans, salt swamps, salty rivers and ponds. Most are microscopic, but some can grow as large as grapes.[11]

References

- ↑ Amoeba at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Leidy, Joseph (1878). "Amoeba proteus". The American Naturalist 12 (4): 235–238. doi:10.1086/272082. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0147%28187804%2912%3A4%3C235%3AAP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-7. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ Audouin, Jean-Victor; et al (1826). Dictionnaire classique d'histoire naturelle. Rey et Gravier. pp. 5. http://books.google.com/books?id=1I8DAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA158&lpg=PA158&dq=%22bory+de+saint+vincent+jean+baptiste+genevieve+marcellin%22+amibe&source=web&ots=SCcqmYPPSy&sig=vje4JuVmdQzWrFqpXTw2UjRsgx8#PPA5,M1.

- ↑ McGrath, Kimberley; Blachford, Stacey (eds.) (2001). Gale Encyclopedia of Science Vol. 1: Aardvark-Catalyst (2nd ed.). Gale Group. ISBN 078764370X. OCLC 46337140.

- ↑ Eugene H. Johnson, Jeffrey J. Windsor, and C. Graham Clark Emerging from Obscurity: Biological, Clinical, and Diagnostic Aspects of Dientamoeba fragilis.

- ↑ "Amoeba proteus". Amoebae on the Web. http://amoeba.ifmo.ru/species/amoebidae/aprot.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ MacIver, Sutherland. "Isolation of Amoebae". The Amoebae. http://www.bms.ed.ac.uk/research/others/smaciver/Protocols/AmoebaProts/isolation_of_amoebae.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Amoeba". Scienceclarified.com. http://www.scienceclarified.com/Al-As/Amoeba.html.

- ↑ http://www.genomenewsnetwork.org/articles/02_01/Sizing_genomes.shtml

- ↑ Patterson, D.J. (1981). "Contractile vacuole complex behaviour as a diagnostic character for free living amoebae". Protistologica 17: 243–248.

- ↑ https://webspace.utexas.edu/lhc58/protist_slideshow/

External links

- Amoebae: Protists Which Move and Feed Using Pseudopodia, David Patterson (Tree of Life)

- Wikibooks: compare size of cells

- Joseph Leidy's Amoeba Plates

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||