Amide

In chemistry, an amide is usually an organic compound that contains the functional group consisting of an acyl group (R-C=O) linked to a nitrogen atom (N). The term refers both to a class of compounds and a functional group within those compounds. The term amide also refers to deprotonated form of ammonia (NH3) or an amine, often represented as anions R2N-. The remainder of this article is about the carbonyl-nitrogen sense of amide. For discussion of these "anionic amides," see the articles sodium amide and lithium diisopropylamide.

Contents |

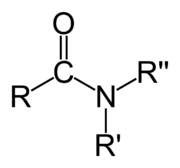

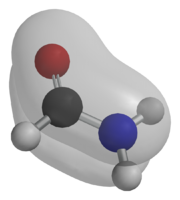

Structure and bonding

The simplest amides are derivatives of ammonia wherein one hydrogen atom has been replaced by an acyl group. The ensemble is generally represented as RC(O)NH2. Closely related and even more numerous are amides derived from primary amines (R'NH2) with the formula RC(O)NHR'. Amides are also commonly derived from secondary amines (R'RNH) with the formula RC(O)NR'R. Amide are usually regarded as derivatives of carboxylic acids in which the hydroxyl group has been replaced by an amine or ammonia.

The lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen is delocalized onto the carbonyl, thus forming a partial double bond between N the carbonyl carbon. Consequently the nitrogen in amides is not pyramidal. It is estimated that acetamide is described by resonance structure A for 62% and by B for 28%[1]

Nomenclature

In the usual nomenclature, one adds the term "amide" to the stem of the parent acid's name. Thus, the simplest amide derived from acetic acid is named acetamide (CH3CONH2). IUPAC recommends ethanamide, but this and related formal names are rarely encountered. When the amide is derived from a primary or secondary amine, the substitutents on nitrogen are indicated first in the name. Thus the amide formed from dimethylamine and acetic acid is N,N-dimethylacetamide (CH3CONMe2, where Me = CH3). Usually even this name is simplified to dimethylacetamide. Cyclic amides are called lactams; they are necessarily secondary or tertiary amides. Functional groups consisting of -P(O)NR2 and -SO2NR2 are phosphonamides and sulfonamides, respectively.

Pronunciation

Some chemists make a pronunciation distinction between the two, saying /əˈmiːd/ for the carbonyl-nitrogen compound and /ˈæmaɪd/ (![]() listen) for the anion. Others substitute one of these with /ˈæmɨd/, while still others pronounce both /ˈæmɨd/, making them homonyms.

listen) for the anion. Others substitute one of these with /ˈæmɨd/, while still others pronounce both /ˈæmɨd/, making them homonyms.

Properties

Basicity

Compared to amines, amides are very weak bases. While the conjugate acid of an amine has a pKa of about 9.5, the conjugate acid of an amide has a pKa around -0.5. Therefore amides don't have as clearly noticeable acid-base properties in water. This lack of basicity is explained by the electron-withdrawing nature of the carbonyl group where the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen is delocalized by resonance. On the other hand, amides are much stronger bases than carboxylic acids, esters, aldehydes, and ketones (conjugated acid pKa between -6 and -10). It is estimated in silico that acetamide is represented by resonance structure A for 62% and by B for 28%.[1] Resonance is largely prevented in the very strained quinuclidone.

Because of the greater electronegativity of oxygen, the carbonyl (C=O) is a stronger dipole than the N-C dipole. The presence of a C=O dipole and, to a lesser extent a N-C dipole, allows amides to act as H-bond acceptors. In primary and secondary amides, the presence of N-H dipoles allows amides to function as H-bond donors as well. Thus amides can participate in hydrogen bonding with water and other protic solvents; the oxygen and nitrogen atoms can accept hydrogen bonds from water and the N-H hydrogen atoms can donate H-bonds. As a result of interactions such as these, the water solubility of amides is greater than that of corresponding hydrocarbons.

The proton of a primary or secondary amide does not dissociate readily under normal conditions; its pKa is usually well above 15. Conversely, under extremely acidic conditions, the carbonyl oxygen can become protonated with a pKa of roughly -1.

Solubility

The solubilities of amides and esters are roughly comparable. Typically amides are less soluble than comparable amines and carboxylic acids since these compounds can both donate and accept hydrogen bonds. Tertiary amides, with the important exception of N,N-dimethylformamide, exhibit low solubility in water.

Characterization

The presence of the functional group is generally easily established, at least in small molecules. They are the most common non-basic functional group. They can be distinguished from nitro and cyano groups by their IR spectra. Amides exhibit a moderately intense νCO band near 1650 cm-1. By 1H NMR spectroscopy, CONHR signals occur at low fields. In X-ray crystallography, the C(O)N center together with the three immediately adjacent atoms characteristically define a plane.

Applications and occurrence

Amides are pervasive in nature and technology as structural materials. The amide linkage is easily formed, confers structural rigidity, and resists hydrolysis. Nylons are polyamides as are the very resilient materials Aramid, Twaron, and Kevlar. Amide linkages in a biochemical context are called peptide linkages. Amide linkages constitute a defining molecular feature of proteins. The secondary structure of which is due in part to the hydrogen bonding abilities of amides. Low molecular weight amides, such as dimethylformamide (HC(O)N(CH3)2) are common solvents. Many drugs are amides, for example penicillin and LSD.

Amide synthesis

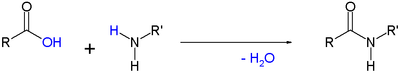

Amides are commonly formed via reactions of a carboxylic acid with an amine. Many methods are known for driving the unfavorable equilibrium to the right:

- RCO2H + R'R"NH

RC(O)NR'R" + H2O

RC(O)NR'R" + H2O

For the most part, these reactions involve "activating" the carboxylic acid and the best known method, the Schotten-Baumann reaction, which involves conversion of the acid to the acid chlorides:

| Reaction name | Substrate | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Beckmann rearrangement | cyclic ketone | reagent: hydroxylamine and acid |

| Schmidt reaction | ketones | reagent: hydrazoic acid |

| nitrile hydrolysis | nitrile | reagent: water; acid catalyst |

| Willgerodt-Kindler reaction | aryl alkyl ketones | sulfur and morpholine |

| Passerini reaction | carboxylic acid, ketone or aldehyde | |

| Ugi reaction | isocyanide, carboxylic acid, ketone, primary amine | |

| Bodroux reaction[2][3] | carboxylic acid, Grignard reagent with an aniline derivative ArNHR' | |

| Chapman rearrangement[4] | aryl imino ether | for N,N-diaryl amides. The reaction mechanism is based on a nucleophilic aromatic substitution.[5] |

| Leuckert amide synthesis [6] | isocyanate | Reaction of arene with isocyanate catalysed by aluminium trichloride, formation of aromatic amide. |

Other methods

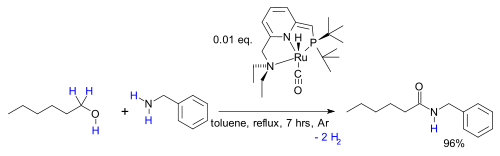

The seemingly simple direct reaction between an alcohol and an amine to an amide was not tried until 2007 when a special ruthenium-based catalyst was reported to be effective in a so-called dehydrogenative acylation:[7]

- The generation of hydrogen gas compensates for unfavorable thermodynamics. The reaction is believed to proceed by one dehydrogenation of the alcohol to the aldehyde followed by formation of a hemiaminal and the after a second dehydrogenation to the amide. Elimination of water in the hemiaminal to the imine is not observed.

Amide reactions

Amides undergo many chemical reactions, usually through an attack on the carbonyl breaking the carbonyl double bond and forming a tetrahedral intermediate. Thiols, hydroxyls and amines are all known to serve as nucleophiles. Owing to their resonance stabilization, amides are less reactive under physiological conditions than esters. Enzymes, e.g. peptidases or artificial catalysts, are known to accelerate the hydrolysis reactions. They can be hydrolysed in hot alkali, as well as in strong acidic conditions. Acidic conditions yield the carboxylic acid and the ammonium ion while basic hydrolysis yield the carboxylate ion and ammonia. Amides are also versatile precursors to many other functional groups.

| Reaction name | Product | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| dehydration | nitrile | reagent: phosphorus pentoxide |

| Hofmann rearrangement | amine with one fewer carbon atoms | reagents: bromine and sodium hydroxide |

| amide reduction) | amine | reagent: lithium aluminium hydride |

| Vilsmeier-Haack reaction | imine | POCl3, aromatic substrate, formamide |

| Nitosation | carboxylic acid (and N2) | nitrous acid (generated in situ) |

External links

- Amide synthesis (coupling reaction) - Synthetic protocols from organic-reaction.com

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Amide Resonance" Correlates with a Breadth of C-N Rotation Barriers Carl R. Kemnitz and Mark J. Loewen J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2007; 129(9) pp 2521 - 2528; (Article) doi:10.1021/ja0663024

- ↑ Bodroux F., Bull. Soc. Chim. France, 1905, 33, 831;

- ↑ Bodroux reaction at the Institute of Chemistry, Skopje, Macedonia Link

- ↑ A. W. Chapman, "CCLXIX. - Imino-aryl ethers. Part III. The molecular rearrangement of N-phenylbenziminophenyl ether", Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions, 127:1992-1998, 1925. doi:10.1039/CT9252701992

- ↑ Advanced organic Chemistry, Reactions, mechanisms and structure 3ed. Jerry March ISBN 0-471-85472-7

- ↑ Ueber einige Reaktionen der aromatischen Cyanate R. Leuckart Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft Volume 18 Issue 1, Pages 873 - 877 1885doi:10.1002/cber.188501801182

- ↑ Direct Synthesis of Amides from Alcohols and Amines with Liberation of H2 Chidambaram Gunanathan, Yehoshoa Ben-David, David Milstein Science 10 August 2007: Vol. 317. no. 5839, pp. 790 - 792 doi:10.1126/science.1145295

External links

|

||||||||