Zolpidem

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| N,N,6-Trimethyl-2-(4-methylphenyl)- imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-acetamide |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 82626-48-0 |

| ATC code | N05CF02 |

| PubChem | CID 5732 |

| DrugBank | APRD00095 |

| ChemSpider | 5530 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C19H21N3O |

| Mol. mass | 307.395 g/mol |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 70% (oral) 92% bound in plasma |

| Metabolism | Hepatic - CYP3A4 |

| Half-life | 2 to 2.9 hours |

| Excretion | 56% renal 34% fecal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | B3(AU) C(US) |

| Legal status | Schedule IV (US) Class C (UK) |

| Routes | Oral (tablet), Sublingual, Oromucosal (spray) |

| |

|

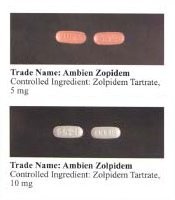

Zolpidem is a prescription medication used for the short-term treatment of insomnia, as well as some brain disorders. It is a short-acting nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic that potentiates gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter, by binding to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptors at the same location as benzodiazepines.[1] It works quickly (usually within 15 minutes) and has a short half-life (2–3 hours). Trade names of zolpidem include Adormix, Ambien, Ambien CR, Edluar, Zolpimist, Damixan, Hypnogen, Ivedal, Lioran, Myslee, Nasen, Nytamel, Sanval, Somidem, Stilnoct, Stilnox, Stilnox CR, Sucedal, Zoldem, Zolnod and Zolpihexal.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Zolpidem has not adequately demonstrated effectiveness in maintaining sleep.[8] Its hypnotic effects are similar to those of the benzodiazepine class of drugs, but it is molecularly distinct from the classical benzodiazepine molecule and is classified as an imidazopyridine. Flumazenil, a benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, which is used for benzodiazepine overdose, can also reverse zolpidem's sedative/hypnotic and memory impairing effects.[9][10]

As an anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant, the beneficial effects start to emerge at 10 and 20 times the dose required for sedation, respectively.[11] For that reason, it has never been approved for either muscle relaxation or seizure prevention. Such drastically increased doses are more inclined to induce one or more negative side-effects, including hallucinations and amnesia.

Zolpidem is one of the most common benzodiazepine related sleeping medications prescribed in the Netherlands, with a total of 582,660 prescriptions dispensed in 2008.[12] The patent in the United States on zolpidem was held by the French pharmaceutical corporation Sanofi-Aventis.[13] On April 23, 2007 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 13 generic versions of zolpidem tartrate.[14] Zolpidem is available from several generic manufacturers in the UK, as a generic from Sandoz in South Africa, TEVA in Israel, as well as from other manufacturers such as Ratiopharm (Germany).

Contents |

Indications

Insomnia

Zolpidem is approved for the short-term (usually about two to six weeks) treatment of insomnia, and it has been studied for nightly use up to six months in a single-blind trial published in 1991,[15] an open-label study lasting 180 days published in 1992 (with continued efficacy in patients who had kept taking it as of 180 days after the end of the trial),[16] and in an open-label trial lasting 179 days published in 1993.[17] Zolpidem has not proven effective in maintaining sleep and is more used for sleep initiation problems.[8]

The United States Air Force uses zolpidem as one of the hypnotics approved as "no-go pills" to help aviators and special duty personnel sleep in support of mission readiness. "Ground tests" are required prior to authorization being issued to use the medication in an operational situation.[18]

Brain injury

A case study performed at the Toulouse University Hospital using PET showed zolpidem repeatably improves brain function and mobility of a patient immobilized by akinetic mutism caused by hypoxia.[19]

Recently, zolpidem has been cited in various medical reports mainly in the United Kingdom as waking persistent vegetative state (PVS) patients, and dramatically improving the conditions of people with brain injuries.[20][21][22][23][24] Results from phase IIa trials were expected in June 2007. The trials are being conducted by Regen Therapeutics of the UK, who have a patent pending on this new use for Zolpidem.[25][26]

Coma

Zolpidem has recently been very strongly related to certain instances of patients in a minimally conscious state being brought to a fully conscious state. While it was initially given to these patients to put them to sleep, it actually brought them to a fully conscious state in which they were capable of communicating and interacting for the first time in years. SPECT and PET scans have shown that the use of the drug actually does dramatically increase the activity in areas of the brain in some patients in a minimally conscious state. Large-scale studies are currently being done to see whether it has the same universal effect on all or most patients in a minimally conscious state.[27] It may be that zolpidem's ability to stimulate the brain, particularly in the semi-comatose, may be related to one of its side-effects, which sometimes causes sleepwalking and other activity while asleep, that appears to observers to be fully conscious activity.

Miscellaneous off-label

Zolpidem is also used off-label to treat restless leg syndrome and as an antiemetic.

As is the case with many prescription sedative/hypnotic drugs, it is sometimes used by stimulant users to "come down" after the use of stimulants such as amphetamines, methamphetamine, cocaine, and MDMA (ecstasy).[28]

Side effects

Side-effects at any dose may include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Anterograde amnesia

- Hallucinations, through all physical senses, of varying intensity

- Delusions

- Altered thought patterns

- Ataxia or poor motor coordination, difficulty maintaining balance[29]

- Euphoria and/or dysphoria

- Increased appetite

- Decreased libido

- Amnesia

- Impaired judgment and reasoning

- Uninhibited extroversion in social or interpersonal settings

- Increased impulsivity

- When stopped, rebound insomnia may occur

- Headaches in some people

- Short term memory loss

Some users take zolpidem recreationally for some of these side-effects, notably sedation, hallucinations and euphoria. Zolpidem becomes addictive if taken for extended periods of time, due to drug tolerance and physical dependence or the euphoria it can sometimes produce. Under the influence of the drug, patients may take more zolpidem than is necessary, due to either forgetting that one has already taken a pill (elderly users are particularly at risk here) or knowingly taking more than the prescribed dosage. The release of AmbienCR (zolpidem tartrate extended release) in the United States renewed interest in the drug among recreational drug users.

Some users have reported unexplained sleepwalking while using zolpidem, and a few have reported driving, binge eating, sleep talking, and performing other daily tasks while sleeping. Research by Australia's National Prescribing Service found that these events mostly occur after the first dosage taken or within a few days of starting therapy.[30] Rare reports of sexual parasomnia episodes related to zolpidem intake have also been reported.[31] The sleepwalker can sometimes perform these tasks as normally as they might if they were awake. They can sometimes carry on complex conversations and respond appropriately to questions or statements so much so that the observer may believe the sleepwalker to be awake. This is similar to, but unlike, typical sleep talking, which can usually be identified easily and is characterised by incoherent speech that often has no relevance to the situation or that is so disorganised as to be completely unintelligible. A person under the influence of this medication may seem fully aware of their environment even though they are still asleep. This can bring about concerns for the safety of the sleepwalker and others. These side-effects may be related to the mechanism that also causes zolpidem to produce its hypnotic properties.[32] It is unclear whether the drug is responsible for the behavior, but a class-action lawsuit was filed against Sanofi-Aventis in March 2006 on behalf of those that reported symptoms.[33]

Residual 'hangover' effects such as sleepiness, impaired psychomotor and cognitive after nighttime administration may persist into the next day which may impair the ability of users to drive safely, increase risks of falls and hip fractures.[34]

The Sydney Morning Herald in Australia reported in 2007 that a man who fell 30 meters to his death from a high-rise unit balcony may have been sleepwalking under the influence of Stilnox. The coverage prompted over 40 readers to contact the newspaper with their own accounts of Stilnox-related automatism, and as of March 2007[update], the drug was under review by the Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee.[35]

In February 2008, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration attached a Black Box Warning to zolpidem, stating that "Zolpidem may be associated with potentially dangerous complex sleep-related behaviours which may include sleep walking, sleep driving and other bizarre behaviours. Zolpidem is not to be taken with alcohol. Caution is needed with other CNS depressant drugs. Limit use to four weeks maximum under close medical supervision."[36] This report received widespread media coverage[37] after the death of Australian student Mairead Costigan, who fell 20m from the Sydney Harbour Bridge while under the influence of Stilnox.[38]

Tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal

A review medical publication found that long term use of zolpidem is associated with drug tolerance, drug dependence, rebound insomnia and CNS related adverse effects. It was recommended that zolpidem be used for short periods of time using the lowest effective dose. Non-pharmacological treatment options however, were found to have sustained improvements in sleep quality.[39] Animal studies of the tolerance inducing properties have shown that in rodents zolpidem has less tolerance producing potential than benzodiazepines but in primates the tolerance producing potential of zolpidem was the same as that of benzodiazepines.[40] Tolerance can develop in some people to the effects of zolpidem in just a few weeks. Abrupt withdrawal of zolpidem may cause delirium, seizures or other severe effects, especially if used for prolonged periods and at high dosages.[41][42][43]

When drug tolerance and physical dependence to zolpidem has developed, treatment usually entails a gradual dose reduction over a period of months in order to minimise withdrawal symptoms which can resemble those seen during benzodiazepine withdrawal. Failing that, an alternative method which may be necessary for some patients is a switch to a benzodiazepine equivalent dose of a longer acting benzodiazepine drug such as diazepam or chlordiazepoxide followed by a gradual reduction in dosage of the long acting benzodiazepine. Sometimes for difficult to treat patients an inpatient flumazenil rapid detoxification program can be used to detox from a zolpidem drug dependence or addiction.[44]

Alcohol has cross tolerance with GABAa receptor positive modulators such as the benzodiazepines and the nonbenzodiazepine drugs. For this reason alcoholics or recovering alcoholics may be at increased risk of physical dependency on zolpidem. Also, alcoholics and drug abusers may be at increased risk of abusing and or becoming psychologically dependent on zolpidem. Zolpidem should be avoided in those with a history of Alcoholism, drug misuse, or in those with history of physical dependency or psychological dependency on sedative-hypnotic drugs.

Special precautions

Driving

Use of zolpidem may impair driving skills with a resultant increased risk of road traffic accidents. This adverse effect is not unique to zolpidem but also occurs with other hypnotic drugs. Caution should be exercised by motor vehicle drivers.[45]

Elderly

The elderly are more sensitive to the effects of hypnotics including zolpidem. Zolpidem causes an increased risk of falls and may induce cognitive adverse effects.[46]

An extensive review of the medical literature regarding the management of insomnia and the elderly found that there is considerable evidence of the effectiveness and durability of non-drug treatments for insomnia in adults of all ages and that these interventions are underutilized. Compared with the benzodiazepines, the nonbenzodiazepine (including zolpidem) sedative-hypnotics appeared to offer few, if any, significant clinical advantages in efficacy or tolerability in elderly persons. It was found that newer agents with novel mechanisms of action and improved safety profiles, such as the melatonin agonists, hold promise for the management of chronic insomnia in elderly people. Long-term use of sedative-hypnotics for insomnia lacks an evidence base and has traditionally been discouraged for reasons that include concerns about such potential adverse drug effects as cognitive impairment (anterograde amnesia), daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls. In addition, the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of these agents remain to be determined. It was concluded that more research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of treatment and the most appropriate management strategy for elderly persons with chronic insomnia.[47]

Gastrointestinal reflux disease

Taking zolpidem dramatically increases the duration of gastroesophageal reflux events, as patients are less likely to become aroused from the event and initiate a swallowing reflex. Patients suffering from gastroesophageal reflux disease had reflux events measured to be significantly longer when taking zolpidem than on placebo. (The same trend was found for reflux events in patients without GERD). This is assumed to be due to suppression of arousal during the reflux event, which would normally result in a swallowing reflex to clear gastric acid from the esophagus. Patients with GERD who take zolpidem thus experience significantly higher esophageal exposure to gastric acid, which increases the likelihood of developing esophageal cancer.[48]

Mechanism of action

Due to its selective binding, Zolpidem has very weak anxiolytic, myorelaxant and anticonvulsant properties but very strong hypnotic properties.[49] Zolpidem binds with high affinity and acts as a full agonist at the α1 containing GABAA receptors, about 10-fold lower affinity for those containing the α2 - and α3 - GABAA receptor subunits, and with no appreciable affinity for α5 subunit containing receptors.[50][51] ω1 type GABAA receptors are the α1 containing GABAA receptors and ω2 GABAA receptors are the α2, α3, α4, α5 and α6 containing GABAA receptors. ω1 GABAA receptors are primarily found in the brain whereas ω2 receptors are primarily found in the spine. Thus zolpidem has a preferential binding for the GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor complex in the brain but a low affinity for the GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor complex in the spine.[52]

Like the vast majority of benzodiazepine-like molecules, zolpidem has no affinity for α4 and α6 subunit-containing receptors.[53] Zolpidem positively modulates GABAA receptors, probably by increasing the GABAA receptor complexes apparent affinity for GABA, without affecting desensitization or peak current.[54] Zolpidem increases slow wave sleep and caused no effect on stage 2 sleep in laboratory tests.[55]

A meta-analysis of the randomised controlled clinical trials that compared benzodiazepines against Z-drugs such as zolpidem has shown that there are few consistent differences between zolpidem and benzodiazepines in terms of sleep onset latency, total sleep duration, number of awakenings, quality of sleep, adverse events, tolerance, rebound insomnia, and daytime alertness.[56]

Drug-drug interactions

Notable drug-drug interactions with the pharmacokinetics of zolpidem include the following drugs chlorpromazine, fluconazole, imipramine, itraconazole, ketoconazole, rifampicin, ritonavir. Interactions with carbamazepine and phenytoin can be expected based on their metabolic pathways but have not yet been studied. There does not appear to be any interaction between zolpidem and cimetidine and rantidine. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3253224 [57]

Overdose

An overdose of zolpidem may cause excessive sedation, pin-point pupils, depressed respiratory function, which may progress to coma and possibly death. Zolpidem combined with alcohol, opiates or other CNS depressants may be even more likely to lead to fatal overdoses. Zolpidem overdosage can be treated with the benzodiazepine receptor antagonist flumazenil, which displaces zolpidem from its binding site the benzodiazepine receptor and therefore rapidly reverses the effects of zolpidem.[58]

Detection in body fluids

Zolpidem may be quantitated in blood or plasma to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, provide evidence in an impaired driving arrest or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma zolpidem concentrations are usually in a range of 30-300 μg/L in persons receiving the drug therapeutically, 100-700 μg/L in those arrested for impaired driving and 1000-7000 μg/L in victims of acute overdosage. Analytical techniques generally involve gas or liquid chromatography.[59][60][61]

Recreational use

Zolpidem has a potential for either medical misuse when the drug is continued long term without or against medical advice, or recreational use when the drug is taken to achieve a high.[62] The transition from medical use of zolpidem to high dose addiction or drug dependence can occur when used without a doctor's recommendation to continue using it, when physiological drug tolerance leads to higher doses than the usual 5 mg or 10 mg, when consumed through insufflation or injection, or when taken for purposes other than as a sleep aid. Misuse is more prevalent in those that have been dependent on other drugs in the past, but tolerance and drug dependence can still sometimes occur in those without a history of drug dependence. Chronic users of high doses are more likely to have a severe physical dependence on the drug which may cause severe withdrawal symptoms including seizures if abrupt withdrawal from zolpidem occurs.[63]

One case history report involved a woman detoxing off a high dose of zolpidem experiencing a generalized seizure, with clinical withdrawal and dependence effects reported to be similar to the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.[64]

In the U.S., recreational use of zolpidem is becoming more common. Recreational users claim that "fighting" the effects of the drug by forcing themselves to stay awake will sometimes cause vivid visuals and a body high. Some users report decreased anxiety, mild euphoria, perceptual changes, visual distortions, and hallucinations.[65]

Zolpidem can be used to facilitate sexual assault.[66][67]

Zolpidem and other sedative hypnotic drugs are detected frequently in cases of people suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. Other drugs including the benzodiazepines and zopiclone are also found in high numbers of suspected drugged drivers. Many drivers have blood levels far exceeding the therapeutic dose range suggesting a high degree of excessive-use potential for benzodiazepines, zolpidem and zopiclone.[68] U.S. Congressman Patrick J. Kennedy says that he was using Zolpidem (Ambien) and Phenergan when caught driving erratically at 3AM.[69] "I simply do not remember getting out of bed, being pulled over by the police, or being cited for three driving infractions," Kennedy said.

See also

- Alpidem

- Imidazopyridine

- Nonbenzodiazepine

- Rebound effect

- Z-drugs

References

- ↑ Lemmer B (2007). "The sleep-wake cycle and sleeping pills". Physiol. Behav. 90 (2-3): 285–93. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.006. PMID 17049955.

- ↑ Ambien.com (2004). "AMBIEN Prescribing Information". Information About a Short-term Treatment for Insomnia - Ambien.com Home Page for Health-care Professionals. Sanofi-Synthelabo Inc. New York, NY 10016. http://www.ambien.com/hcp/index.asp. Retrieved 2005-06-27.

- ↑ Somidem product information

- ↑ STILNOX (zolpidem tartrate) PRODUCT INFORMATION Sanofi-Synthelabo Australia Pty Limited. April 15, 2004

- ↑ "sanofi-aventis : Drugs and Products - CNS - Stilnox/Ambien/Myslee". 2006-11-07. http://en.sanofi-aventis.com/group/products/p_group_products_nervous_stilnox.asp?ComponentID=1267&SourcePageID=1207#3. Retrieved 2006-11-22.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine Names". http://www.non-benzodiazepines.org.uk/benzodiazepine-names.html#Zolpidem.

- ↑ "Complete Zolpidem Tartrate Information from Drugs.com". http://www.drugs.com/ppa/zolpidem-tartrate.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rosenberg, RP. (Jan-Mar 2006). "Sleep maintenance insomnia: strengths and weaknesses of current pharmacologic therapies.". Ann Clin Psychiatry 18 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1080/10401230500464711. PMID 16517453.

- ↑ Patat A; Naef MM, van Gessel E, Forster A, Dubruc C, Rosenzweig P (October 1994). "Flumazenil antagonizes the central effects of zolpidem, an imidazopyridine hypnotic". Clin Pharmacol Ther 56 (4): 430–6. PMID 7955804.

- ↑ Wesensten NJ; Balkin TJ, Davis HQ, Belenky GL (September 1995). "Reversal of triazolam- and zolpidem-induced memory impairment by flumazenil". Psychopharmacology (Berl) 121 (2): 242–9. doi:10.1007/BF02245635. PMID 8545530.

- ↑ Depoortere H, Zivkovic B, Lloyd KG, Sanger DJ, Perrault G, Langer SZ, Bartholini G (1986). "Zolpidem, a novel nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic. I. Neuropharmacological and behavioral effects". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 237 (2): 649–58. PMID 2871178. http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/237/2/649.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ US 4382938, Kaplan J-P, George P, "Imidazo[1,2-a] pyridine derivatives and their application as pharmaceuticals", published 1983-05-10, issued 1984-07-17, assigned to Synthelabo

- ↑ "FDA Approves First Generic Versions of Ambien (Zolpidem Tartrate) for the Treatment of Insomnia". http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2007/ucm108897.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ↑ Schlich D, L'Heritier C, Coquelin JP, Attali P, Kryrein HJ (1991). "Long-term treatment of insomnia with zolpidem: a multicentre general practitioner study of 107 patients". J. Int. Med. Res. 19 (3): 271–9. PMID 1670039.

- ↑ Maarek L, Cramer P, Attali P, Coquelin JP, Morselli PL (1992). "The safety and efficacy of zolpidem in insomniac patients: a long-term open study in general practice". J. Int. Med. Res. 20 (2): 162–70. PMID 1521672.

- ↑ Kummer J, Guendel L, Linden J, Eich FX, Attali P, Coquelin JP, Kyrein HJ (1993). "Long-term polysomnographic study of the efficacy and safety of zolpidem in elderly psychiatric in-patients with insomnia". J. Int. Med. Res. 21 (4): 171–84. PMID 8112475.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Brefel-Courbon C, Payoux P, Ory F, Sommet A, Slaoui T, Raboyeau G, Lemesle B, Puel M, Montastruc JL, Demonet JF, Cardebat D (July 2007). "Clinical and imaging evidence of zolpidem effect in hypoxic encephalopathy". Ann. Neurol. 62 (1): 102–5. doi:10.1002/ana.21110. PMID 17357126.

- ↑ Clauss RP, Güldenpfennig WM, Nel HW, Sathekge MM, Venkannagari RR (2000). "Extraordinary arousal from semi-comatose state on zolpidem. A case report". S. Afr. Med. J. 90 (1): 68–72. PMID 10721397.

- ↑ "Pill 'reverses' vegetative state". BBC. 2006-05-23. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/5008744.stm. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- ↑ Pidd, Helen (2006-09-12). "Reborn". the Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/medicine/story/0,,1870279,00.html. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- ↑ "Judge rejects right-to-die plea by family". The Guardian. 2006-11-20. http://society.guardian.co.uk/health/news/0,,1952341,00.html. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- ↑ Childs, Dan (2007-03-13). "Could a Sleeping Pill 'Wake Up' Coma Patients?". ABC News. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=2947406&page=1. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ↑ "Pill 'reverses' vegetative state" BBC News, 23 May 2006, retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ↑ Pharmalicensing.com, retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ↑ Dziedzic J (September 2007). "Minimally conscious patient makes strides following deep brain stimulation". Neurology Reviews 15 (9). http://www.neurologyreviews.com/07sep/dbs.html.

- ↑ Evidente VG, Caviness JN, Adler CH (2003). "Case studies in movement disorders". Seminars in neurology 23 (3): 277–84. doi:10.1055/s-2003-814739. PMID 14722823.

- ↑ Yasui M, Kato A, Kanemasa T, Murata S, Nishitomi K, Koike K, Tai N, Shinohara S, Tokomura M, Horiuchi M, Abe K (2005). "[Pharmacological profiles of benzodiazepinergic hypnotics and correlations with receptor subtypes] [Pharmacological profiles of benzodiazepinergic hypnotics and correlations with receptor subtypes]" (in Japanese). Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi = Japanese Journal of Psychopharmacology 25 (3): 143–51. PMID 16045197.

- ↑ NPS Position Statement: Zolpidem and sleep-related behaviours (2008). Available at http://nps.org.au/news_and_media/media_releases/repository/zolpidem_stilnox_info_for_prescribers

- ↑ Schenck, CH.; Arnulf, I.; Mahowald, MW. (Jun 2007). "Sleep and sex: what can go wrong? A review of the literature on sleep related disorders and abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences.". Sleep 30 (6): 683–702. PMID 17580590.

- ↑ Dolder CR, Nelson MH (2008). "Hypnosedative-induced complex behaviours : incidence, mechanisms and management". CNS Drugs 22 (12): 1021–36. doi:10.2165/0023210-200822120-00005. PMID 18998740.

- ↑ Perchance To ... Eat?

- ↑ Vermeeren A (2004). "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS drugs 18 (5): 297–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115.

- ↑ Gilmore, Heath (2007-03-11). "Sleeping pill safety under federal review". the Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/sleeping-pill-safety-under-federal-review/2007/03/10/1173478729115.html. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- ↑ "Zolpidem ("Stilnox") - updated information - February 2008". www.tga.gov.au. http://www.tga.gov.au/alerts/stilnox2.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ "Stilnox warnings upgraded" (2008).The Sydney Morning Herald. Available at http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/stilnox-pill-warnings-upgraded/2008/08/11/1218306743431.html

- ↑ Bachl, Matt (2008). "Stilnox blamed for Harbour Bridge death". nineMSN News. Available at http://news.ninemsn.com.au/article.aspx?id=381502

- ↑ Kirkwood CK (1999). "Management of insomnia". J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 39 (5): 688–96; quiz 713–4. PMID 10533351.

- ↑ Petroski RE, Pomeroy JE, Das R (April 2006). "Indiplon is a high-affinity positive allosteric modulator with selectivity for alpha1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 317 (1): 369–77. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.096701. PMID 16399882. http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/317/1/369.

- ↑ Harter C, Piffl-Boniolo E, Rave-Schwank M (November 1999). "[Development of drug withdrawal delirium after dependence on zolpidem and zoplicone] [Development of drug withdrawal delirium after dependence on zolpidem and zoplicone]" (in German). Psychiatr Prax 26 (6): 309. PMID 10627964.

- ↑ "Hypnotic dependence: zolpidem and zopiclone too". Prescrire Int 10 (51): 15. February 2001. PMID 11503851.

- ↑ Sethi PK, Khandelwal DC (February 2005). "Zolpidem at supratherapeutic doses can cause drug abuse, dependence and withdrawal seizure" (PDF). J Assoc Physicians India 53: 139–40. PMID 15847035. http://www.japi.org/february2005/CR-139.pdf.

- ↑ Quaglio G; Lugoboni F, Fornasiero A, Lechi A, Gerra G, Mezzelani P (September 2005). "Dependence on zolpidem: two case reports of detoxification with flumazenil infusion". Int Clin Psychopharmacol 20 (5): 285–7. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000166404.41850.b4. PMID 16096519.

- ↑ Gustavsen I, Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, Engeland A, Neutel I, Mørland J (December 2008). "Road traffic accident risk related to prescriptions of the hypnotics zopiclone, zolpidem, flunitrazepam and nitrazepam". Sleep Med. 9 (8): 818–22. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.011. PMID 18226959. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1389-9457(07)00424-8.

- ↑ Antai-Otong D (August 2006). "The art of prescribing. Risks and benefits of non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists in the treatment of acute primary insomnia in older adults". Perspect Psychiatr Care 42 (3): 196–200. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00070.x. PMID 16916422. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118727940/abstract.

- ↑ Bain KT (June 2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 4 (2): 168–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- ↑ Gagliardi GS, Shah AP, Goldstein M, Denua-Rivera S, Doghramji K, Cohen S, Dimarino AJ (September 2009). "Effect of zolpidem on the sleep arousal response to nocturnal esophageal acid exposure". Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 (9): 948–52. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.026. PMID 19426833.

- ↑ Salvà P, Costa J (September 1995). "Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem. Therapeutic implications". Clin Pharmacokinet 29 (3): 142–53. doi:10.2165/00003088-199529030-00002. PMID 8521677.

- ↑ Pritchett DB, Seeburg PH (1990). "Gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor alpha 5-subunit creates novel type II benzodiazepine receptor pharmacology". J. Neurochem. 54 (5): 1802–4. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01237.x. PMID 2157817.

- ↑ Smith, AJ.; Alder, L.; Silk, J.; Adkins, C.; Fletcher, AE.; Scales, T.; Kerby, J.; Marshall, G. et al. (May 2001). "Effect of alpha subunit on allosteric modulation of ion channel function in stably expressed human recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors determined using (36)Cl ion flux." (PDF). Mol Pharmacol 59 (5): 1108–18. PMID 11306694. http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org/content/59/5/1108.full.pdf.

- ↑ Rowlett JK, Woolverton WL (November 1996). "Assessment of benzodiazepine receptor heterogeneity in vivo: apparent pA2 and pKB analyses from behavioral studies". Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 128 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1007/s002130050103. PMID 8944400. http://link.springer.de/link/service/journals/00213/bibs/6128001/61280001.htm.

- ↑ Wafford KA, Thompson SA, Thomas D, Sikela J, Wilcox AS, Whiting PJ (1996). "Functional characterization of human gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors containing the alpha 4 subunit". Mol. Pharmacol. 50 (3): 670–8. PMID 8794909. http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/50/3/670.

- ↑ Perrais D, Ropert N (1999). "Effect of zolpidem on miniature IPSCs and occupancy of postsynaptic GABAA receptors in central synapses". J. Neurosci. 19 (2): 578–88. PMID 9880578. http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/abstract/19/2/578.

- ↑ Noguchi H, Kitazumi K, Mori M, Shiba T (2004). "Electroencephalographic properties of zaleplon, a non-benzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic, in rats". J. Pharmacol. Sci. 94 (3): 246–51. doi:10.1254/jphs.94.246. PMID 15037809. "WARNING: The reference indicates that zaleplon-Sonata, not zolpidem, increases Slow-wave sleep".

- ↑ Dündar Y, Dodd S, Strobl J, Boland A, Dickson R, Walley T (2004). "Comparative efficacy of newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human psychopharmacology 19 (5): 305–22. doi:10.1002/hup.594. PMID 15252823.

- ↑ Wang JS, DeVane CL (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of the sedative hypnotics" (PDF). Psychopharmacol Bull 37 (1): 10–29. PMID 14561946. http://www.medworksmedia.com/psychopharmbulletin/pdf/12/010-029_PB%20W03_Wang_final.pdf.

- ↑ Lheureux P, Debailleul G, De Witte O, Askenasi R (1990). "Zolpidem intoxication mimicking narcotic overdose: response to flumazenil". Human & experimental toxicology 9 (2): 105–7. doi:10.1177/096032719000900209. PMID 2111156.

- ↑ Jones AW, Holmgren A, Kugelberg FC. Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results. Ther. Drug Monit. 29: 248-260, 2007.

- ↑ Gock SB, Wong SH, Nuwayhid N, Venuti SE, Kelley PD, Teggatz JR, Jentzen JM. Acute zolpidem overdose--report of two cases. J. Anal. Toxicol. 23: 559-562, 1999.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1673-1675.

- ↑ Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". J Clin Psychiatry 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- ↑ Barrero-Hernández FJ, Ruiz-Veguilla M, López-López MI, Casado-Torres A (2002). "[Epileptic seizures as a sign of abstinence from chronic consumption of zolpidem] [Epileptic seizures as a sign of abstinence from chronic consumption of zolpidem]" (in Spanish; Castilian). Rev Neurol 34 (3): 253–6. PMID 12022074.

- ↑ Cubała WJ, Landowski J (2007). "Seizure following sudden zolpidem withdrawal". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 31 (2): 539–40. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.07.009. PMID 16950552.

- ↑ "ksl.com - Ambien Abuse on Rise Among Teens". www.ksl.com. http://www.ksl.com/index.php?nid=248&sid=588181. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ PMID 17340077 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0341

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Jones AW, Holmgren A, Kugelberg FC (2007). "Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results". Therapeutic drug monitoring 29 (2): 248–60. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. PMID 17417081.

- ↑ Kennedy To Enter Drug Rehab After Car Crash; Congressman Wrecked Car Near Capitol

External links

- Joel Lamoure RPh. BScPhm.,FASCP. "How Is Zolpidem Dependence Managed?". Medscape Pharmacists Ask the Expert. WebMD. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/717142. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- "Prescription Sleep Aid AMBIEN CR". Sanofi-Aventis. http://www.ambiencr.com. Retrieved 2009-05-21. "Ambien CR official website"

- "Ambien Cr (zolpidem tartrate) Tablet, Coated". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Health & Human Services. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?id=5420. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- "Zolpidem (Ambien)". The Vaults of Erowid. 2007-07-19. http://www.erowid.org/pharms/zolpidem/zolpidem.shtml. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- Angelettie L, Kelley-Soderholm E. "Ambien Abuse". Mental Health Site. BellaOnline, Minerva WebWorks LLC. http://www.bellaonline.com/articles/art22470.asp. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- Ian Jackson. "Ambien Stories". Ambien Forum. http://www.ambienoverdose.org. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Zolpidem

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||