Allegheny Mountains

| Allegheny Mountains | |

| Range | |

View from atop Spruce Knob, the highest point in the Alleghenies.

|

|

| Country | |

|---|---|

| States | Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia |

| Part of | Ridge-and-valley Appalachians |

| Borders on | Cumberland Mountains |

| Highest point | Spruce Knob of Spruce Mountain |

| - location | Pendleton County, WV |

| - elevation | 4,863 ft (1,482.2 m) |

| - coordinates | |

| Geology | Sandstone, Quartzite |

| Orogeny | Alleghenian orogeny |

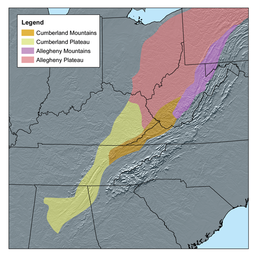

Map showing the Allegheny Mountains in purple.

|

|

The Allegheny Mountain Range (also spelled Alleghany and Allegany, pronounced /ælɨˈɡeɪni/) — informally, the Alleghenies — is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the eastern United States and Canada. It has a northeast-southwest orientation and runs for about 400 miles (640 km) from north-central Pennsylvania, through western Maryland and eastern West Virginia, to southwestern Virginia.

The Alleghenies comprise the rugged western-central portion of the Appalachians. They rise to approximately 4,862 feet (1,483 m) in northeastern West Virginia. In the east, they are dominated by a high, steep escarpment known as the Allegheny Front. In the west, they grade down into the closely associated Allegheny Plateau which extends into Ohio and Kentucky.

Contents |

Name

The name derives from the Allegheny River, which drains only a small portion of the Alleghenies in west-central Pennsylvania. The meaning of the word, which comes from the Lenape (Delaware) Indians, is not definitively known but is usually translated as "fine river". A Lenape legend tells of an ancient tribe called the "Allegewi" who lived on the river and were defeated by the Lenape.[1] Allegheny is the early French spelling (as in Allegheny River, which was once part of New France), and Allegany is the early English spelling (as in Allegany County, Maryland, a former British Colony).

The word "Allegheny" was once commonly used to refer to the whole of what are now called the Appalachian Mountains. John Norton used it (spelled variously) around 1810 to refer to the mountains in Tennessee and Georgia.[2] Around the same time, Washington Irving proposed renaming the United States either "Appalachia" or "Alleghania".[1] In 1861, Arnold Henry Guyot published the first systematic geologic study of the whole mountain range.[3] His map labeled the range as the "Alleghanies", but his book was titled On the Appalachian Mountain System. As late as 1867, John Muir — in his book A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf — used the word "Alleghanies" in referring to the southern Appalachians.

There was no general agreement about the "Appalachians" versus the "Alleghanies" until the late 19th century.[1]

Geography

Extent

From northeast to southwest, the Allegheny Mountains run about 400 miles (640 km). From west to east, at their widest, they are about 100 miles (160 km).

Although there are no official boundaries to the Allegheny Mountains region, it may be generally defined to the east by the Great Valley (locally called the Cumberland Valley in Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia); to the north by the Susquehanna River valley; and to the south by the New River valley. To the west, the Alleghenies grade down into the dissected Allegheny Plateau (of which they are sometimes considered to be a part). The westernmost ridges are considered to be the Laurel and Chestnut Ridges in Pennsylvania and Laurel and Rich Mountains in West Virginia.

The mountains to the south of the Alleghenies — the Appalachians in westernmost Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and eastern Tennessee — are the Cumberlands. The Alleghenies and the Cumberlands both constitute part of the Ridge and Valley Province of the Appalachians.

Allegheny Front and Allegheny Highlands

The eastern edge of the Alleghenies is marked by the Allegheny Front, which is also sometimes considered the eastern terminus of the Allegheny Plateau. This great escarpment roughly follows a portion of the Eastern Continental Divide in this area. A number of impressive gorges and valleys drain the Alleghenies: to the east, Smoke Hole Canyon (South Branch Potomac River) and the Shenandoah Valley, and to the west the New River Gorge and the Blackwater and Cheat Canyons. Thus, about half the precipitation falling on the Alleghenies makes its way west to the Mississippi and half goes east to Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic seaboard.

The highest ridges of the Alleghenies are just west of the Front, which has an east/west elevational change of up to 3,000 feet (910 m). Absolute elevations of the Allegheny Highlands reach nearly 5,000 feet (1,500 m), with the highest elevations in the southern part of the range. The highest point in the Allegheny Mountains is Spruce Knob (4,863 ft/1,482 m), on Spruce Mountain in West Virginia. Other notable Allegheny highpoints include Thorny Flat on Cheat Mountain (4,848 ft/1478 m), Bald Knob on Back Allegheny Mountain (4,842 ft/1476 m), and Mount Porte Crayon (4,770 ft/1,454 m), all in West Virginia; Dans Mountain (2,898 ft/883m) in Maryland, Backbone Mountain (3360 ft/1024 m), the highest point in Maryland; Mount Davis (3,213 ft/979 m), the highest point in Pennsylvania, and the second highest, Blue Knob (3,146 ft/959 m).

Development

There are very few sizable cities in the Alleghenies. The four largest are (in descending order of population): Altoona, State College, Johnstown (all in Pennsylvania) and Cumberland (in Maryland). In the 1970s and '80s, the Interstate Highway System was extended into the northern portion of the Alleghenies and this region is now serviced by a network of federal expressways — Interstates 80, 70/76 and 68. Interstate 64 also traverses the southern extremity of the range, but the Central Alleghenies (the "High Alleghenies" of eastern West Virginia) has posed special problems for highway planners owing to the region's very rugged terrain and environmental sensitivities (see Corridor H.) This region is still serviced by a rather sparse secondary highway system and remains considerably lower in population density than surrounding regions.

Protected areas

Much of the Monongahela (West Virginia), George Washington (West Virginia, Virginia) and Jefferson (Virginia) National Forests lie within the Allegheny Mountains. The Alleghenies also include a number of federally-designated wilderness areas, such as the Dolly Sods Wilderness, Laurel Fork Wilderness, and Cranberry Wilderness in West Virginia.

The mostly completed Allegheny Trail, a project of the West Virginia Scenic Trails Association since 1975, runs the length of the range within West Virginia. The northern terminus is at the Mason-Dixon Line and the southern is at the West Virginia-Virginia border on Peters Mountain.[4]

Geology

The bedrock of the Alleghenies is mostly sandstone and metamorphosed sandstone, quartzite, which is extremely resistant to weathering. Prominent beds of resistant conglomerate can be found in some areas, such as the Dolly Sods. When it weathers, it leaves behind a pure white quartzite gravel. The rock layers of the Alleghenies were formed during the Appalachian orogeny.

Because of intense freeze-thaw cycles in the higher Alleghenies, there is little native bedrock exposed in most areas. The ground surface usually rests on a massive jumble of sandstone rocks, with air space between them, that are gradually moving down-slope. The crest of the Allegheny Front is an exception, where high bluffs are often exposed.

Ecology

Flora

The High Alleghenies are noted for their forests of red spruce, balsam fir, and mountain ash, trees typically found much farther north. The forests of the entire region are now almost all second- or third-growth forests, the original trees having been removed in the late 19th and (in West Virginia) early 20th centuries. The northern Alleghennies and the Allegheny Plateau in New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio were originally covered in a mixed forest of American beech and Eastern hemlock but this too has been almost entirely removed or replanted (see Allegheny Highlands forests).

Fauna

These mountains and plateau have over twenty species of reptiles represented as lizard, skink, turtle and snake. Some of the Icterid birds visit the mountains as well as the hermit thrush and wood thrush. North American migrant birds live throughout the mountains during the warmer seasons. Occasionally, osprey and eagles can be found nesting along the streams. The hawks and owls are the most common birds of prey.

Mammals in the region include whitetail deer, chipmunk, raccoon, skunk, groundhog, opossum, weasel, field mouse, flying squirrel, cotton-tail rabbit, gray foxes, red foxes, gray squirrels, red squirrels and a cave bat to name a few. Bobcat, snowshoe hare, wild boar and black bear are also found in the forests and parks of the Alleghenies. The mink, beaver and eastern cougar (Puma concolor couguar) have become very rarily seen.

The water habitat of the Alleghenies holds 24 families of fish. Amphibian species number about twenty one. Among them are hellbenders, salamanders, toads and frogs. The Alleghenies provide habitat for about 54 species of common invertebrate. These include Gastropoda, slugs, leech, earthworms and grub worm. cave crayfish (Cambarus nerterius) live alongside a little over seven dozen cave invertebrates.[5]

History

Pre-contact Native Americans

The prehistoric people inhabiting the Allegheny Mountains emerged from the greater region's archaic and mound building cultures, particularly the Adena and Eastern Woodland peoples with a later Hopewellian influence. These Late Middle Woodland culture people have been called the Montaine (ca. A.D. 500 to 1000) culture [6][7]. Their neighbors, the woodland Buck Garden Culture, lived in the western valleys of the central Allegheny range. The Montaine sites extend from the tributaries of the upper Potomac River region south to the New River tributaries. These also were influenced by the earlier Armstrong Culture[8] of the more southwestern portions northern sub-range of the Ouasioto (Cumberland) Mountains and by the more easterly Virginia Woodland people. The Late Woodland Montaine were less influenced by Hopewellian trade from Ohio, although similarly polished stone tools have been found among the Montaine sites in the Tygart Valley.[9] Small groups of Montaine people appear to have lingered much beyond their classically defined period in parts of the most mountainous valleys.[10]

The watershed of the Monongahela River is within the northwestern Alleghenies, and it is from it that the Monongahela culture takes its name. The Godwin-Portman site (36AL39) located in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, had a possible Fort Ancient (ca. AD 850 to 1680) presence during the 15th century[11]. Washington Boro ceramics have been found on the Barton (18AG3) and Llewellyn (18AG26) sites in Maryland on the northeastern slopes of the late Susquehannock sequence. The early Monongahela (ca. AD 900 to 1630) are called the Drew Tradition in Pennsylvania. According to Richard L. George: "I believe that some of the Monongahela were of Algonquin origin.... Other scholars have suggested that Iroquoian speakers were interacting with Late Monongahela people, and additional evidence is presented to confirm this. I conclude that the archaeologically conceived term, Monongahela, likely encompasses speakers of several languages, including Siouan."[12] According to Dr Maslowski of West Virginia in 2009: "The New River Drainage and upper Potomac represents the range of the Huffman Phase (Page) hunting and gathering area or when it is found in small amounts on village sites, trade ware or Page women being assimulated into another village (tribe)." Finally, according to Prof Potter of Virginia, they [the people represented by the Huffman Phase of Page pottery] had occupied the eastern slopes of the Alleghenies on the upper Potomac to the northern, lower Shenandoah Valley region before the A.D. 1300 Luray Phase (Algonquian) peoples' "invasion". It is thought that these ancient Alleghenians were pushed from the classic Huffman Phase of the eastern slopes of the Alleghenies to the Blue Ridge Mountains in western Virginia, which was eastern Siouan territory.

In 1669, John Lederer and members of his party became the first Europeans to crest the Blue Ridge Mountains and the first to see the Shenandoah Valley and the Allegheny Mountains beyond.

Native Americans in the 17th century

The proto-historic Alleghenies can be exampled by the earliest journals of the colonists. According to Batts and Fallows' September, 1671 Expedition, they found Mehetan Indians of Mountain "Cherokee-Iroquois" mix on the New River tributaries. This journal does not identify the "Salt Village", but, that the "Mehetan" were associated with these and today thought to be "Monetons", Siouans. However, this journal does not identify the "Salt Village" below the Kanawha Falls, but, that simply the "Mehetan" were associated with these. He explained, below the "Salt Villages", a mass of hostile Indians had, implied, arrived and some believe these to be "Shanwans" of Vielles Expedition of 1692~94, ancient Shawnee. In 1669, John Lederer of Maryland for the Virginia Colony and the Tennessee Cherokee had visited the mouth of the Kanawha and reported no hostilities on the lower streams of the Alleghenies. The Mohetan representative through a Siouan translator explained to Mr Batts and Mr Fallon, Colonel Abraham Woods exploriers 1671-2, the he (Moheton Native American) could not say much about the people below the "Salt Village" because they (Mountain Cherokee) were not associated with them. The Mohetan was armed by this time of 1671 for the Mohetan Representative was given several pouches of ammunition for his and the other's weapons as a token of friendship. Somebody had already been trading within the central Alleghenies before the Virignians historical record begins in the Allegheny Mountains. Some earlier scholars found evidence these Proto-historics were either Cistercians of Spanish Ajacan Occuquan outpost on the Potomac River or Jesuits and their Kahnawake Praying Indians (Mohawk) on the Riviere de la Ronceverte. The "Kanawha Madonna" may date from this period or earlier. Where the New River breaks through Peters’ Mountain, near Pearisburg Virginia the 1671 journal mentions the "Moketans had formerly lived."

According to a number of early 17th century maps, the Messawomeake or "Mincquas" (Dutch) occupied the northern Allegheny Mountains. The "Shatteras" (an ancient Tutelo) occupied the Ouasioto Mountains and the earliest term Canaraguy (Kanawhans otherwise Canawest[13]) on the 1671 French map occupied the southerly Alleghenies. They were associated with the Allegheny "Cherokee" and Eastern Siouan as trade-movers and canoe transporters. The Calicuas, an ancient most northern Cherokee, migrated or was pushed from the Central Ohio Valley onto the north eastern slopes of the Alleghenies of the ancient Messawomeake, Iroquois tradesmen to 1630s Kent Island, by 1710 maps. Sometime before 1712, the Canawest ("Kanawhans"-"Canallaway"-"Canaragay") had moved to the upper Potomac and made a Treaty with the newly established trading post of Fort Conolloway which would become a part of western Maryland during the 1740s.

White trading posts and other settlements

Prior to European exploration and settlement, trails through the Alleghenies had been transited for many generations by American Indian tribes such as the Iroquois, Shawnee, Delaware, Catawba and others, for purposes of trade, hunting and, especially, warfare.[14] Western Virginia "Cherokee" were reported at Cherokee Falls, today's Valley Falls of the Tygart Valley.[15] Indian trader Charles Poke's trading post dates from 1731 with the Calicuas of Cherokee Falls still in the region from the previous century.

The "London Scribes" (The Crown's taxation records) vaguely mentions the colonial Alleghenian location of only a few other early colonial trading locations. A general knowledge of these few outposts are more of traditional telling of some local people. However, an example is the "Van Metre" trading house mentioned in an earlier edition of the "Wonderful West Virginia Magazine" being on the South Branches of the upper reaches of the Potomac. Another very early trading house appears on a lower Greenbrier Valley map during the earlier decades of the 18th century.

As early as 1719, new arrivals from Europe began to cross the lower Susquehanna River and settle illegally in defiance of the Board of Property in Pennsylvania, on un-warranted land of the northeastern drainage rivers of the Allegheny Mountains. Several Indian Nations requested the removal of "Maryland Intruders".[16] Some of these moved onward as territory opened up beyond the Alleghenies.

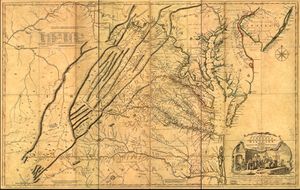

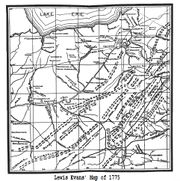

First surveys

Among the first whites to penetrate into the Allegheny Mountains were surveyors attempting to settle a dispute over the extent of lands belonging to either Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron or to the English Privy Council. An expedition of 1736 by John Savage established the location of the source of the North Branch Potomac River. An expedition ten years later by Peter Jefferson and Thomas Lewis emplaced the “Fairfax Stone” at the source and established a line of demarcation (the “Fairfax Line”) extending from the stone south-east to the headwaters of the Rappahannock River. Lewis' journal of that expedition provides a valuable view of the Allegheny country before its settlement.[17] Jefferson and Joshua Fry's "Fry-Jefferson Map" of 1751 accurately depicted the Alleghenies for the first time.

In the following decades, pioneer settlers arrived in the Alleghenies, especially during Colonial Virginia's Robert Dinwiddie era (1751–58). These included squatters by the Quit-rent Law. Some had preceded the official surveyors using a "hack on the tree and field of corn" marking land ownership approved by the Virginia Colonial Governor who had to be replaced with Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore.

First roads

Trans-Allegheny travel had been facilitated when a military trail — Braddock Road — was blazed and opened by the Ohio Company in 1751. (It followed an earlier Indian and pioneer trail known as Nemacolin's Path.) Braddock Road connected Cumberland, Maryland (the upper limit of navigation on the Potomac River) and the forks of the Ohio River (the future Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). It received its name from the British leader of the French and Indian War, General Edward Braddock, who led the ill-fated Braddock expedition four years later.[18]

In addition to the war, hunting and trading with Indians were primary motivations for white movement across the mountains. Permanent white settlement of the northern Alleghenies was facilitated by the explorations and stories of such noted Marylanders as the Indian fighter and trader Thomas Cresap (1702–90) and the backwoodsman and hunter Meshach Browning (1781–1859).[19]

The Braddock Road was superseded by the Cumberland Road (also called the National Road), one of the first major improved highways in the United States to be built by the federal government. Construction began in 1811 at Cumberland and the road reached Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia) on the Ohio River in 1818.

First railroads

Construction on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began at Baltimore in 1828; the B&O traversed the Alleghenies, changing the economy and society of the Mountains forever. The B&O had reached Martinsburg, (West) Virginia by May 1842, Hancock, (West) Virginia, by June, Cumberland, Maryland, on November 5, 1842, Piedmont, (West) Virginia on July 21, 1851 and Fairmont, Virginia on June 22, 1852. (It finally reached its Ohio River terminus at Wheeling, (West) Virginia on January 1, 1853.)

Civil War

Lying astride the Mason-Dixon Line — traditional dividing line between "North" and "South" in the eastern United States — the Alleghenies were among the areas most directly affected by the American Civil War (1861–1865). The very rugged terrain, however, was not amenable to a large-scale maneuver war and so the actions that the area witnessed were generally guerrilla in nature.

The coal and timber industries

The 20th century

Dr. Martin Luther King referenced the Allegheny Mountains in his famous "I Have a Dream" speech (1963), when he said "Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!"

Photo gallery

North Fork Mountain, West Virginia, looking south |

Blue Knob, Pennsylvania, the northernmost 3,000 footer in the Alleghenies. |

Shenandoah Mountain, at the easternmost limit of the Alleghenies. |

Laurel Mountain, West Virginia, at the westernmost limit of the Alleghenies. |

|

New River Gorge, Section of the cliff at Beauty Mountain. |

Germany Valley, a scenic upland valley of eastern West Virginia. |

The Blackwater Canyon, a rugged gorge in eastern West Virginia. |

Cheat Canyon, in Coopers Rock State Forest, northeastern West Virginia. |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Stewart, George R. (1967), Names on the Land, Boston.

- ↑ Norton, Major John (1816), The Journal of Major John Norton (Toronto: Champlain Society, Reprinted 1970)

- ↑ Guyot, Arnold, “On the Appalachian Mountain System”, American Journal of Science and Arts, Second Series, XXXI, (March 1861), 167-171.

- ↑ Rosier, George L., Compiler, Hiking Guide to the Allegheny Trail, Second edition, West Virginia Scenic Trails Association, Kingwood, W.Va., 1990.

- ↑ West Virginia DNR - Wildlife Resources, West Virginia Division of Wildlife. and http://lutra.dnr.state.wv.us/cwcp/appendix2.shtm

- ↑ McMichael, WV 1968

- ↑ Dragoo, Pa 1963

- ↑ The late Armstrong Indians existed from about 100 B.C. to 500 AD and were influenced by the Hopewellians

- ↑ McMichael, Edward V., "Introduction to West Virginia Archeology", 2nd Edition, 1968, West Virginia Archeological Society

- ↑ McMichael 1968

- ↑ THE LATE PREHISTORIC COMPONENTS AT THE GODWIN-PORTMAN SITE, 36AL39, abstract RICHARD L. GEORGE. It had several Late Prehistoric occupations. This multicomponent site was destroyed in 1979. The Pennsylvania Archaeologist; Volume 77(1), Spring 2007

- ↑ "Revisiting the Monongahela Linguistic/Cultural Affiliation Mystery", ABSTRACT by Richard L. George, Pennsylvania Archeology Society.

- ↑ Relocated Subjects of the 5 Nations, To my friend Winjack, King of the Ganawese Indians on Sasqua- hanna, "Brother : I have heard that your friends the Nanticokes are now at yr. Town upon their Journey to the five Nations. I know they are a peaceable People that live quietly amongst the English in Mary Land, and therefore I shall be glad to see them, and will be ready to do them any kindness in my power." New Castle, June 16, 1722. Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania By Pennsylvania. Provincial Council, Samuel Hazard, Pennsylvania Committee. To Colo. Juhn French, Francis Worley, & James Mitehell, Esqrs. "Whereas, the three Nations of Indians settled on the North side of the River Sasquahanuah, in His Maties Peace & under the protection of this Government, viz: The Conestogoes, The Shawanoea, & The Cawnoyes, are very much disturbed, and the Peace of thia Colony is hourly in danger of being broken by persons, who pursuing their own private gain without any regard to Justice, Have attempted & others do still threaten to Survey and take up Lauds on the South West Branch of the sd. River, right against the Towns & Settlements of the said Indians, without any Right or pretence of Authority so to do, from the Proprietor of this Province unto whom the Lands unquestionably belong." at Conestogoe, the 18th day of June, in the Eighth year of our Sovereign Lord George. Annoq. Dom. 1722. Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania By Pennsylvania. Provincial Council, Samuel Hazard, Pennsylvania Committee http://books.google.com/books?id=rEwOAAAAIAAJ&lpg=PA188&ots=gqLrLn2dB6&dq=Ganawese&pg=PA188&output=text

- ↑ Smith, J. Lawrence, The High Alleghenies: The Drama and Heritage of Three Centuries, Tornado, West Virginia: Allegheny Vistas; Illustrations by Bill Pitzer, 1982.

- ↑ Wonderful West Virginia articles "Allegeny" and Wonderfull W.Virginia September1973, Pp.30, "Valley Falls Of Old", Walter Balderson

- ↑ "AN EARLY HISTORY OF HELLAM TOWNSHIP", Kreutz Creek Valley Preservation Society, [1] (4/28/2009). Archived 2009-10-25.

- ↑ The Fairfax Line: Thomas Lewis's Journal of 1746; Footnotes and index by John Wayland, Newmarket, Virginia: The Henkel Press (1925 publication).

- ↑ Borneman, Walter R. (2007). The French and Indian War. Rutgers. ISBN 978-0060761851.

- ↑ Browning, Meshach (1859), Forty-Four Years of the Life of a Hunter; Being Reminiscences of Meshach Browning, a Maryland Hunter; Roughly Written Down by Himself, Revised and illustrated by E. Stabler. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co..

References

- McNeill, G.D. (Douglas), The Last Forest, Tales of the Allegheny Woods, n.p., 1940 (Reprinted with preface by Louise McNeill, Pocahontas Communications Cooperative Corporation, Dunmore, W.Va. and McClain Printing Company, Parsons, W.Va, 1989.)

- Core, Earl L. (1967), "Wildflowers of the Alleghenies", J. Alleghenies, 4(l):I, 2-4.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||