Portuguese language

| Portuguese | ||

|---|---|---|

| Português | ||

| Pronunciation | [puɾtuˈɡeʃ] (European), [poχtuˈɡe(j)ʃ] (BP-carioca), [poɾtuˈɡe(j)s] (BP-paulistano), [pɔhtuˈɡejs] (BP-nordestino), [poɾtuˈɡes] (BP-gaúcho)[1] |

|

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Oceania | |

| Total speakers | Native: ≈210 million [2][3] Total:~240 million[4][5] |

|

| Ranking | 5–7 | |

| Language family | Indo-European | |

| Writing system | Latin alphabet (Portuguese variant) | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

9 countries

1 dependent entity

Numerous international organisations |

|

| Regulated by | International Portuguese Language Institute; CPLP; Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazil); Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, Classe de Letras (Portugal) | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | pt | |

| ISO 639-2 | por | |

| ISO 639-3 | por | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Portuguese (português or língua portuguesa) is a Romance language that grew from the Latin descended Galician-Portuguese language that was spoken in the mediaeval Kingdom of Galicia, whose territory is now divided between northern Portugal, Galicia and Asturias. It also absorbed influences from the Romance and Arabic languages spoken in the areas that were conquered by the Portuguese reconquista. It was spread worldwide in the 15th and 16th centuries as Portugal established a colonial empire (1415–1999) that included Brazil in South America, Goa and other parts of India, Macau in China, Timor in South-East Asia and the five African countries that make up the PALOP lusophone area: Cape Verde, Guiné-Bissau, São Tomé e Príncipe, Angola and Mozambique. It was used as the exclusive lingua franca on the island of Sri Lanka for almost 350 years. During that time, many creole languages based on Portuguese also appeared around the world, in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

With over 260 million speakers, is the fifth most spoken language in the world, the most widely spoken in the southern hemisphere, and the third most spoken in the Western world. In addition to Brazil and Portugal, it is used in Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Macau, Mozambique, São Tome and Principe, East Timor and (since 2007) Equatorial Guinea, as well as in the former territories of Portuguese India (Goa, Daman, Isle of Angediva, Simbor, Gogol, Diu and Dadra and Nagar Haveli) and in small communities that were part of the Portuguese Empire in Asia as Malacca, Malaysia and East Africa as Zanzibar, Tanzania. It has official status in the European Union (EU), Mercosur (Mercosul in Portuguese), the African Union, the Organization of American States (OAS), the Latin Union, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP) and the Association of National Olympic Committees of Portuguese Official Language (ACOLOP).

Like other languages, Portuguese has experienced a historical evolution, being influenced by many other languages and dialects, as it reached the form known today. Contemporary Portuguese comprises several dialects and sub-dialects (subfalares), often very distinct, and two internationally recognized standards (European Portuguese and Brazilian Portuguese). At present, Portuguese is the only language spoken in the Western world with over a hundred million people with two official orthographies (spelling differences between English as used in various countries are not isolated but divergent spellings). This situation must be resolved by agreement (Speller 1990).

Today it is one of the world's major languages, ranked seventh according to number of native speakers (between 205 and 230 million). It is the language of about half of South America's population, even though Brazil is the only Portuguese-speaking nation in the Americas. It is also a major lingua franca in Portugal's former colonial possessions in Africa. It is an official language in nine countries (see the table on the right), also being co-official with Cantonese Chinese in Macau and Tetum in East Timor. There are sizeable communities of Portuguese speakers in various regions of North America, notably in the United States (New Jersey, New England, California and south Florida) and in Ontario, Canada (especially Toronto).

In various aspects, the system of sounds in Portuguese is more similar to the phonologies of Catalan or French than, say, those of Spanish or Italian. Nevertheless, the grammar, structure and vocabulary of the Portuguese and Spanish languages are so similar that phonetic differences do not impede intelligibility between them in any significant way. Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes once called Portuguese "the sweet language",[6] Lope de Vega referred to it as "sweet" [7] while Brazilian writer Olavo Bilac poetically described it as a última flor do Lácio, inculta e bela: "the last flower of Latium, wild and beautiful". Portuguese is also termed "the language of Camões",[8] after one of Portugal's best known literary figures, Luís Vaz de Camões.

Portuguese is also the fourth most learned language in the world, since at least 30 million students study this language. The mandatory offering of Portuguese in school curricula is observed in Uruguay,[9] and Argentina,[10] and similar legislation is being considered in Venezuela,[11] Zambia,[12] Congo,[13] Senegal,[13] Namibia,[13] Swaziland,[13] Côte d'Ivoire,[13] and South Africa.[13]

Contents |

Geographic distribution

Today, Portuguese is the official language of Angola, Brazil (190.6 million),[14] Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Portugal (10.6 million),[15] São Tomé and Príncipe and Mozambique.[16] It is also one of the official languages of East Timor (with Tetum) and the Chinese special administrative region of Macau (with Chinese). It is the language of most of the population in Portugal, Brazil, São Tomé and Príncipe and Angola. And is the most widely spoken language in Mozambique though only 6.5% are native speakers. No data is available for Cape Verde, but almost all the population is bilingual, and the monolingual population speaks Cape Verdean Creole.[17]

Small Portuguese-speaking communities subsist in former overseas colonies of Portugal such as Macau, where it is spoken by 7% of the population, and East Timor (13.6%). In addition, there are several Portuguese-based creole languages that are spoken around the world.

Uruguay gave Portuguese an equal status to Spanish in its educational system at the north border with Brazil. In the rest of the country, it is taught as an obligatory subject beginning in the 6th grade.[18]

It is also spoken by substantial immigrant communities, though not official, in Andorra, Australia,[19] France, Luxembourg, Jersey (with a statistically significant Portuguese-speaking community of approximately 10,000 people), Paraguay, Namibia, South Africa, Switzerland, Venezuela, Japan[20] and the U.S. states of California, Connecticut,[21] Florida,[22] Massachusetts, New Jersey,[23] New York[24] and Rhode Island.[25] In some parts of India, such as Goa[26] and Daman and Diu,[27] Portuguese is still spoken. There are also significant populations of Portuguese speakers in Canada (mainly concentrated in and around Toronto and Montreal),[28] Bermuda[29] and the Netherlands Antilles.

Portuguese is an official language of several international organizations. The Community of Portuguese Language Countries[16] (with the Portuguese acronym CPLP) consists of the eight independent countries that have Portuguese as an official language. It is also an official language of the European Union, accounting for 3% of its population,[30] Mercosul, the Organization of American States, the Organization of Ibero-American States, the Union of South American Nations, and the African Union (one of the working languages) and one of the official languages of other organizations. The Portuguese language is gaining popularity in Africa, Asia, and South America as a second language for study.

Portuguese and Spanish are the fastest-growing European languages after English, and according to estimates by UNESCO, the Portuguese language has the highest potential for growth as an international language in southern Africa and South America. The Portuguese-speaking African countries are expected to have a combined population of 83 million by 2050. In total, the Portuguese-speaking countries will have 335 million people by the same year. Since 1991, when Brazil signed into the economic market of Mercosul with other South American nations, such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay, there has been an increase in interest in the study of Portuguese in those South American countries. The demographic weight of Brazil in the continent will continue to strengthen the presence of the language in the region. Although in the early 21st century, after Macau was ceded to China in 1999, the use of Portuguese was in decline in Asia, it is becoming a language of opportunity there; mostly because of East Timor's boost in the number of speakers in the last five years but also because of increased Chinese diplomatic and financial ties with Portuguese-speaking countries.

In July 2007, President Teodoro Obiang Nguema announced his government's decision to establish Portuguese as Equatorial Guinea's third official language, to meet the requirements to apply for full membership of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries. This upgrading from its current Associate Observer condition would result in Equatorial Guinea being able to access several professional and academic exchange programs and the facilitation of cross-border circulation of citizens. Its application is currently being assessed by other CPLP members.[31]

In March 1994 the Bosque de Portugal (Portugal's Woods) was founded in the Brazilian city of Curitiba. The park houses the Portuguese Language Memorial, which honors the Portuguese immigrants and the countries that adopted the Portuguese language. Originally there were seven nations represented with pillars, but the independence of East Timor brought yet another pillar for that nation in 2007.

In March 2006, the Museum of the Portuguese Language, an interactive museum about the Portuguese language, was founded in São Paulo, Brazil, the city with the greatest number of Portuguese speakers in the world.

Dialects

Portuguese is a pluricentric language with two main groups of dialects, those of Brazil and those of the Old World. For historical reasons, the dialects of Africa and Asia are generally closer to those of Portugal than the Brazilian dialects, although in some aspects of their phonetics, especially the pronunciation of unstressed vowels, they resemble Brazilian Portuguese more than European Portuguese. They have not been studied as widely as European and Brazilian Portuguese.

Audio samples of some dialects of Portuguese are available below.[32] There are some differences between the areas but these are the best approximations possible. For example, the caipira dialect has some differences from the one of Minas Gerais, but in general it is very close. A good example of Brazilian Portuguese may be found in the capital city, Brasília, because of the generalized population from all parts of the country.

Angola

Angola

- Benguelense—Benguela province.

Luandense—Luanda province.

Luandense—Luanda province.- Sulista—South of Angola.

- Huambense—Huambo province.

Brazil

Brazil

- Caipira—States of São Paulo (countryside; the city of São Paulo and the eastern areas of the state have their own accent, called paulistano); southern Minas Gerais, northern Paraná, southeastern Mato Grosso do Sul.

- Cearense—Ceará.

- Baiano—Bahia.

Fluminense—Variants spoken in the states of Rio de Janeiro (excluding the city of Rio de Janeiro and its adjacent metropolitan areas, which have their own dialect, called carioca).

Fluminense—Variants spoken in the states of Rio de Janeiro (excluding the city of Rio de Janeiro and its adjacent metropolitan areas, which have their own dialect, called carioca).- Gaúcho—Rio Grande do Sul. (There are many distinct accents in Rio Grande do Sul, mainly due to the heavy influx of European immigrants of diverse origins, who have settled in colonies throughout the state.)

- Mineiro—Minas Gerais (not prevalent in the Triângulo Mineiro; includes southern and southeastern Minas Gerais; the city of Belo Horizonte has an accent of its own.).

Nordestino—northeastern states of Brazil (Pernambuco, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte have a particular way of speaking).[33]

Nordestino—northeastern states of Brazil (Pernambuco, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte have a particular way of speaking).[33]- Nortista—Amazon Basin states.

- Paulistano—Variants spoken around São Paulo city and some eastern areas of São Paulo state.

- Sertanejo—States of Goiás and Mato Grosso.

- Sulista—Variants spoken in the areas between the northern regions of Rio Grande do Sul and southern regions of São Paulo state. (The cities of Curitiba and Florianópolis have fairly distinct accents as well.)

- Carioca—Variants spoken in Rio de Janeiro City and Niteroi.

- Brasiliense—Variant only spoken in Brasília, due to many waves of immigration, attracted by the government in order to build Brasília.

Portugal

Portugal

Açoriano (Azorean)—Azores.

Açoriano (Azorean)—Azores. Alentejano—Alentejo (Alentejan Portuguese)

Alentejano—Alentejo (Alentejan Portuguese) Algarvio—Algarve (there is a particular dialect in a small part of western Algarve).

Algarvio—Algarve (there is a particular dialect in a small part of western Algarve). Alto-Minhoto—North of Braga (hinterland).

Alto-Minhoto—North of Braga (hinterland). Baixo-Beirão; Alto-Alentejano—Central Portugal (hinterland).

Baixo-Beirão; Alto-Alentejano—Central Portugal (hinterland). Beirão—Central Portugal.

Beirão—Central Portugal. Estremenho—Regions of Coimbra , Leiria and Lisbon (the Lisbon dialect has some peculiar features not shared with the one of Coimbra).

Estremenho—Regions of Coimbra , Leiria and Lisbon (the Lisbon dialect has some peculiar features not shared with the one of Coimbra). Madeirense (Madeiran)—Madeira.

Madeirense (Madeiran)—Madeira. Nortenho—Regions of Braga and Porto.

Nortenho—Regions of Braga and Porto. Transmontano—Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro.

Transmontano—Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro.- Barranquenho—Barrancos.

- Lisboeta—Lisboa.

Other countries

Cape Verde—

Cape Verde— Português cabo-verdiano (Cape Verdean Portuguese)

Português cabo-verdiano (Cape Verdean Portuguese) Daman and Diu, India—Damaense (Damanese Portuguese)

Daman and Diu, India—Damaense (Damanese Portuguese) East Timor—

East Timor— Timorense (East Timorese Portuguese)

Timorense (East Timorese Portuguese) Goa, India—Goês (Goan Portuguese)

Goa, India—Goês (Goan Portuguese) Guinea-Bissau—

Guinea-Bissau— Guineense (Guinean Portuguese)

Guineense (Guinean Portuguese) Macau—

Macau— Macaense (Macanese Portuguese)

Macaense (Macanese Portuguese) Mozambique—

Mozambique— Moçambicano (Mozambican Portuguese)

Moçambicano (Mozambican Portuguese) São Tomé and Príncipe—

São Tomé and Príncipe— Santomense (São Tomean Portuguese)

Santomense (São Tomean Portuguese) Uruguay—Dialectos Portugueses del Uruguay (DPU)

Uruguay—Dialectos Portugueses del Uruguay (DPU)

Differences between dialects are mostly of accent and vocabulary, but between the Brazilian dialects and other dialects, especially in their most colloquial forms, there can also be some grammatical differences. The Portuguese-based creoles spoken in various parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas are independent languages that should not be confused with Portuguese.

History

Arriving in the Iberian Peninsula in 216 BC, the Romans brought with them the Latin language, from which all Romance languages descend. The language was spread by arriving Roman soldiers, settlers, and merchants, who built Roman cities mostly near the settlements of previous civilizations.

| Medieval Portuguese poetry |

|---|

| Das que vejo |

| nom desejo |

| outra senhor se vós nom, |

| e desejo |

| tam sobejo, |

| mataria um leon, |

| senhor do meu coraçom: |

| fim roseta, |

| bela sobre toda fror, |

| fim roseta, |

| nom me meta |

| em tal coita voss'amor! |

| João de Lobeira (c. 1270–1330) |

Between 409 and 711 AD, as the Roman Empire collapsed in Western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula was conquered by Germanic peoples (Migration Period). The occupiers, mainly Suebi and Visigoths, quickly adopted late Roman culture and the Vulgar Latin dialects of the peninsula. After the Moorish invasion of 711, Arabic became the administrative language in the conquered regions, but most of the population continued to speak a form of Romance commonly known as Mozarabic. The influence exerted by Arabic on the Romance dialects spoken in the Christian kingdoms was small, affecting mainly their lexicon.

The earliest surviving records of a distinctively Portuguese language are administrative documents of the 9th century, still interspersed with many Latin phrases. Today this phase is known as Proto-Portuguese (between the 9th and the 12th centuries). In the first period of Old Portuguese—Galician-Portuguese Period (from the 12th to the 14th century)—the language gradually came into general use. For some time, it was the language of preference for lyric poetry in Christian Hispania, much as Occitan was the language of the poetry of the troubadours. Portugal became an independent kingdom from the Kingdom of Leon in 1139, under king Afonso I of Portugal. In 1290, king Denis of Portugal created the first Portuguese university in Lisbon (the Estudos Gerais, later moved to Coimbra) and decreed that Portuguese, then simply called the "common language" should be known as the Portuguese language and used officially.

In the second period of Old Portuguese, from the 14th to the 16th centuries, with the Portuguese discoveries, the language was taken to many regions of Asia, Africa and the Americas (nowadays, the great majority of Portuguese speakers live in Brazil, in South America). By the 16th century, it had become a lingua franca in Asia and Africa, used not only for colonial administration and trade but also for communication between local officials and Europeans of all nationalities. Its spread was helped by mixed marriages between Portuguese and local people, and by its association with Roman Catholic missionary efforts, which led to the formation of a creole language called Kristang in many parts of Asia (from the word cristão, "Christian"). The language continued to be popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. Some Portuguese-speaking Christian communities in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia preserved their language even after they were isolated from Portugal.

The end of the Old Portuguese period was marked by the publication of the Cancioneiro Geral by Garcia de Resende, in 1516. The early times of Modern Portuguese, which spans a period from the 16th century to the present day, were characterized by an increase in the number of learned words borrowed from Classical Latin and Classical Greek since the Renaissance, which greatly enriched the lexicon.

Characterization

A distinctive feature of Portuguese is that it, like Sardinian, preserved the stressed vowels of Vulgar Latin, which became diphthongs in other Romance languages; cf. Fr. pierre, Sp. piedra, It. pietra, Ro. piatră, Port. pedra, Sard. perda ("stone"), from Lat. petram; or Sp. fuego, It. fuoco, Fr. feu, Ro. foc, Port. fogo, Sard. fogu from Lat. focus ("fire"). Another characteristic of early Portuguese was the loss of intervocalic l and n, sometimes followed by the merger of the two surrounding vowels, or by the insertion of an epenthetic vowel between them: cf. Lat. salire ("to leave"), tenere ("to have"), catenam ("chain"), Sp. salir, tener, cadena, Port. sair, ter, cadeia.

When the elided consonant was n, it often nasalized the preceding vowel: cf. Lat. manum ("hand"), ranam ("frog"), bonum ("good"), Port. mão, rãa, bõo (now mão, rã, bom). This process was the source of most of the nasal diphthongs typical in Portuguese. In particular, the Latin endings -anem, -anum and -onem became -ão in most cases, cf. Lat. canem ("dog"), germanum ("brother"), rationem ("reason") with Modern Port. cão, irmão, razão, and their plurals -anes, -anos, -ones normally became -ães, -ãos, -ões, cf. cães, irmãos, razões.

Vocabulary

Most of the lexicon of Portuguese is derived from Latin. Nevertheless, because of the Moorish occupation of the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages, and the participation of Portugal in the Age of Discovery, it has adopted loanwords from all over the world.

Very few Portuguese words can be traced to the pre-Roman inhabitants of Portugal, which included the Gallaeci, Lusitanians, Celtici and Cynetes. The Phoenicians and Carthaginians, briefly present, also left some scarce traces. Some notable examples are abóbora "pumpkin" and bezerro "year-old calf", from the nearby Celtiberian language (probably through the Celtici); cerveja "beer", from Celtic; and cachorro "dog", from Basque.

In the 5th century, the Iberian Peninsula (the Roman Hispania) was conquered by the Germanic Suebi and Visigoths. As they adopted the Roman civilization and language, however, these people contributed only a few words to the lexicon, mostly related to warfare—such as espora "spur", estaca "stake", and guerra "war", from Gothic *spaúra, *stakka, and *wirro, respectively. The influence also exists in toponymic and patronymic surnames borne by Visigoth sovereigns and their descendants, and it dwells on placenames such has Ermesinde, Esposende and Resende where sinde and sende are derived from the Germanic "sinths" (military expedition) and in the case of Resende, the prefix re comes from Germanic "reths" (council).

Between the 9th and 13th centuries, Portuguese acquired about 800 words from Arabic (approx. 1,200 or more when you factor in other words also derived from Arabic) by influence of Moorish Iberia. They are often recognizable by the initial Arabic article a(l)-, and include many common words such as aldeia "village" from الضيعة alḍai`a, alface "lettuce" from الخس alkhass, armazém "warehouse" from المخزن almakhzan, and azeite "olive oil" from الزيت azzait. From Arabic came also the grammatically peculiar word oxalá إن شاء الله "hopefully". The Mozambican currency name metical was derived from the word متقال mitqāl, a unit of weight. The word Mozambique itself is from the Arabic name of sultan Muça Alebique (Musa Alibiki).

Starting in the 15th century, the Portuguese maritime explorations led to the introduction of many loanwords from Asian languages. For instance, catana "cutlass" from Japanese katana and chá "tea" from Chinese chá.

From South America came batata "potato", from Taino; ananás and abacaxi, from Tupi-Guarani naná and Tupi ibá cati, respectively (two species of pineapple), and tucano "toucan" from Guarani tucan. See List of Brazil state name etymologies, for some more examples.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, because of the role of Portugal as intermediary in the Atlantic slave trade, and the establishment of large Portuguese colonies in Angola, Mozambique, and Brazil, Portuguese got several words of African and Amerind origin, especially names for most of the animals and plants found in those territories. While those terms are mostly used in the former colonies, many became current in European Portuguese as well. From Kimbundu, for example, came kifumate → cafuné "head caress", kusula → caçula "youngest child", marimbondo "tropical wasp", and kubungula → bungular "to dance like a wizard".

Finally, it has received a steady influx of loanwords from other European languages. For example, melena "hair lock", fiambre "wet-cured ham" (in contrast with presunto "dry-cured ham" from Latin prae-exsuctus "dehydrated"), and castelhano "Castilian", from Spanish; colchete/crochê "bracket"/"crochet", paletó "jacket", batom "lipstick", and filé/filete "steak"/"slice" respectively, from French crochet, paletot, bâton, filet; macarrão "pasta", piloto "pilot", carroça "carriage", and barraca "barrack", from Italian maccherone, pilota, carrozza, baracca; and bife "steak", futebol, revólver, estoque, folclore, time from English beef, football, revolver, stock, folklore, and team.

Portuguese belongs to the West Iberian branch of the Romance languages, and it has special ties with the following members of this group:

- Mirandese, the only recognised regional language spoken in Portugal (beside Portuguese, the only official language in Portugal).

- Galician and Fala, its closest relatives. See below.

- Spanish. (See also Differences between Spanish and Portuguese)

- Leonese.

Despite the obvious lexical and grammatical similarities between Portuguese and other Romance languages, it is not mutually intelligible with them. Apart from Galician and Spanish, Portuguese speakers will usually need some formal study of basic grammar and vocabulary before attaining a reasonable level of comprehension in the other Romance languages, and vice versa.

Galician and the Fala

The closest language to Portuguese is Galician, spoken in the autonomous community of Galicia (northwestern Spain). The two were at one time a single language, known today as Galician-Portuguese, but since the political separation of Portugal from Galicia they have diverged, especially in pronunciation and vocabulary. Nevertheless, the core vocabulary and grammar of Galician are still noticeably closer to Portuguese than to those of Spanish. In particular, like Portuguese, it uses the future subjunctive, the personal infinitive, and the synthetic pluperfect (see the section on the grammar of Portuguese, below). Mutual intelligibility (estimated at 85% by R. A. Hall, Jr., 1989)[34] is very good between Galicians and northern Portuguese, but poorer between Galicians and speakers from central Portugal. For that, many renowned linguists yet consider Galician to be a dialect of the Portuguese language.

The Fala language is another descendant of Galician-Portuguese, spoken by a small number of people in the Spanish towns of Valverde del Fresno, Eljas and San Martín de Trevejo (autonomous community of Extremadura, near the border with Portugal).

Influence on other languages

Portuguese has provided loanwords to many languages, such as Indonesian, Manado Malay, Sri Lankan Tamil and Sinhalese (see Sri Lanka Indo-Portuguese), Malay, Bengali, English, Hindi, Konkani, Marathi, Tetum, Xitsonga, Papiamentu, Japanese, Lanc-Patuá(spoken in northern Brazil), Esan and Sranan Tongo (spoken in Suriname). It left a strong influence on the língua brasílica, a Tupi-Guarani language, which was the most widely spoken in Brazil until the 18th century, and on the language spoken around Sikka in Flores Island, Indonesia. In nearby Larantuka, Portuguese is used for prayers in Holy Week rituals. The Japanese-Portuguese dictionary Nippo Jisho (1603) was the first dictionary of Japanese in a European language, a product of Jesuit missionary activity in Japan. Building on the work of earlier Portuguese missionaries, the Dictionarium Anamiticum, Lusitanum et Latinum (Annamite-Portuguese-Latin dictionary) of Alexandre de Rhodes (1651) introduced the modern orthography of Vietnamese, which is based on the orthography of 17th-century Portuguese. The Romanization of Chinese was also influenced by the Portuguese language (among others), particularly regarding Chinese surnames; one example is Mei. During 1583–88 Italian Jesuits Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci created a Portuguese-Chinese dictionary—the first ever European-Chinese dictionary.[35][36]

Derived languages

Beginning in the 16th century, the extensive contacts between Portuguese travelers and settlers, African slaves, and local populations led to the appearance of many pidgins with varying amounts of Portuguese influence. As each of these pidgins became the mother tongue of succeeding generations, they evolved into fully fledged creole languages, which remained in use in many parts of Asia and Africa until the 18th century. Some Portuguese-based or Portuguese-influenced creoles are still spoken today, by over 3 million people worldwide, especially people of partial Portuguese ancestry.

Movement to make Portuguese an official language of the UN

Justifications

There is a growing number of people in the Portuguese-speaking media and the internet who are presenting the case to the CPLP and other organizations to run a debate in the Lusophone community with the purpose of bringing forward a petition to make Portuguese an official language of the United Nations.

In October 2005, during the international Convention of the Elos Club International that took place in Tavira, Portugal,[37] a petition was written and unanimously approved whose text can be found on the internet with the title Petição Para Tornar Oficial o Idioma Português na ONU. Romulo Alexandre Soares, president of the Brazil-Portugal Chamber highlights that the positioning of Brazil in the international arena as one of the emergent powers of the 21st century, the size of its population, and the presence of the language around the world provides legitimacy and justifies a petition to the UN to make the Portuguese language an official language of the UN.[38]

Challenges

Several factors detract from this campaign. The current official languages of the UN are either 1) official/dominant in many countries (English, Spanish, Arabic, and French) or 2) have several hundreds of millions of speakers (Chinese). English, Spanish, and Arabic fulfill both criteria. Portuguese is a global language in that it is the official tongue of several sovereign countries on four continents. It also has over 200 million speakers. However, it exhibits some noticeable differences when compared to the current 6 UN official languages. For example, English, French, Arabic and Spanish are each official languages of multiple states and of over half of the world's countries. In contrast, four out of every five speakers of the Portuguese-speaking world live in just one country: Brazil. In addition to Brazil, Portuguese is the official language in only 9 other sovereign states; however, English is official in 53 states, French in 29 states, Arabic in 25 states, and Spanish in 20 states.

More significantly, in each part of the world with a Portuguese-speaking country, this language is overshadowed by other powerful languages that are already official languages of the UN. For example, in the Americas, the 190 million Portuguese-speaking Brazilians are overshadowed by the most spoken languages in the Western Hemisphere: Spanish (~360 million speakers) and English (~340 million speakers). Portuguese is overshadowed to an even greater extent in Europe, the continent in which four of the six UN languages originated (English, French, Spanish, and Russian). In the European context, Portuguese is not even among the ten most spoken languages on the continent, with a number of speakers comparable to those of Czech and Bulgarian. In Africa, Portuguese is eclipsed as a continental lingua franca by English and French in countries that surround Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique. Finally in Asia, a continent with several languages that have hundreds of millions of speakers, the only sovereign state with Portuguese as an official language is East Timor, which has only a million people. While Brazilian migration has brought 300,000 fluent Portuguese speakers to Japan, Portuguese does not enjoy any official status whatsoever in that country. Therefore, while Portuguese will gain increasing importance as Brazil continues its development as a major economy, it will likely face the same hurdles that prevented Japanese and German (both languages of major global economies with millions of speakers) from becoming both international languages and official ones of the UN.

Phonology

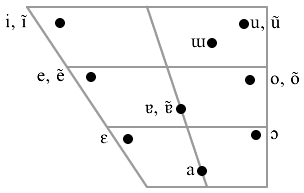

There is a maximum of 9 oral vowels and 19 consonants, though some varieties of the language have fewer phonemes (Brazilian Portuguese has 8 oral vowels). There are also five nasal vowels, which some linguists regard as allophones of the oral vowels, ten oral diphthongs, and five nasal diphthongs. In total, Brazilian Portuguese has 13 vowel phonemes.[39][40]

Vowels

To the seven vowels of Vulgar Latin, European Portuguese has added two near central vowels, one of which tends to be elided in rapid speech, like the e caduc of French (represented as either /ɯ̽/, or /ɨ/, or /ə/). The high vowels /e o/ and the low vowels /ɛ ɔ/ are four distinct phonemes, and they alternate in various forms of apophony. Like Catalan, Portuguese uses vowel quality to contrast stressed syllables with unstressed syllables: isolated vowels tend to be raised, and in some cases centralized, when unstressed. Nasal diphthongs occur mostly at the ends of words.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t̪ | d̪ | k | ɡ | ||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ʁ | |||||||||

| Approximant | j | w | ||||||||||||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||||||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||||||||||

The consonant inventory of Portuguese is fairly conservative. The medieval affricates /ts/, /dz/, /tʃ/, /dʒ/ merged with the fricatives /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, respectively, but not with each other, and there have been no other significant changes to the consonant phonemes since then. However, some notable dialectal variants and allophones have appeared, among which:

- In many regions of Brazil, /t/ and /d/ have the affricate allophones [tʃ] and [dʒ], respectively, before /i/ and /ĩ/. (Quebec French has a similar phenomenon, with alveolar affricates instead of postalveolars. Japanese is another example).

- At the end of a syllable, the phoneme /l/ has the allophone [u̯] in Brazilian Portuguese (L-vocalization).

- In many parts of Brazil and Angola, intervocalic /ɲ/ is pronounced as a nasalized palatal approximant [ȷ̃], which nasalizes the preceding vowel, so that, for instance, /ˈniɲu/ is pronounced [ˈnĩȷ̃u].

- In most of Brazil, the alveolar sibilants /s/ and /z/ occur in complementary distribution at the ends of syllables, depending on whether the consonant that follows is voiceless or voiced, as in English. But in most of Portugal and parts of Brazil, sibilants are postalveolar at the ends of syllables, /ʃ/ before voiceless consonants, and /ʒ/ before voiced consonants (in Judeo-Spanish, /s/ is often replaced with /ʃ/ at the ends of syllables, too).

- There is considerable dialectal variation in the value of the rhotic phoneme /ʁ/. See Guttural R in Portuguese, for details.

- In Portugal, the voiced stops [b d̪ ɡ] are pronounced as the corresponding voiced fricatives [β ð ɣ] between vowels.

Examples of different pronunciation

- Excerpt from the Portuguese national epic Os Lusíadas, by author Luís de Camões (I, 33)

| Original | IPA (European Portuguese) | IPA (Brazilian Portuguese) | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustentava contra ele Vénus bela, | suʃtẽˈtavɐ ˈkõtɾɐ ˈelɨ ˈvɛnuʒ ˈbɛlɐ | sustẽˈtavɐ ˈkõtɾɐ ˈeli ˈvẽnuz ˈbɛlɐ | Held against him the lovely Venus |

| Afeiçoada à gente Lusitana, | ɐfɐjsuˈada ˈʒẽtɨ luziˈtɐnɐ | afejsuˈada ˈʒẽtʃi luziˈtɐ̃nɐ | Fondly to the people of Portugal, |

| Por quantas qualidades via nela | puɾ ˈkwɐ̃tɐʃ kwɐliˈdadɨʒ ˈviɐ ˈnɛlɐ | puɾ ˈkwɐ̃tɐs kwaliˈdadʒiz ˈviɐ ˈnɛlɐ | For many qualities he saw in her |

| Da antiga tão amada sua Romana; | dãˈtiɡɐ tɐ̃w̃ ɐˈmadɐ ˈsuɐ ʁuˈmɐnɐ | dãˈtʃiɡɐ tɐ̃w̃ ɐ̃ˈmadɐ ˈsuɐ hoˈmɐ̃nɐ | From his old beloved Roman; |

| Nos fortes corações, na grande estrela, |

nuʃ ˈfɔɾtɨʃ kuɾɐˈsõȷ̃ʒ nɐ ˈɡɾɐ̃dɨʃˈtɾelɐ |

nus ˈfɔɾtʃis koɾaˈsõȷ̃z na ˈɡɾɐ̃dʒisˈtɾelɐ |

In the stout hearts, in the big star |

| Que mostraram na terra Tingitana, | kɨ muʃˈtɾaɾɐ̃w̃ nɐ ˈtɛʁɐ tĩʒiˈtɐnɐ | ki mosˈtɾaɾɐ̃w̃ na ˈtɛhɐ tʃĩʒiˈtɐ̃nɐ | That showed in the land Tingitana, |

| E na língua, na qual quando imagina, | i nɐ ˈlĩɡwɐ nɐ kwaɫ ˈkwɐ̃dw imɐˈʒinɐ | i na ˈlĩɡwɐ na kwaw ˈkwɐ̃dimaˈʒĩnɐ | And in the language, which when it is imagined |

| Com pouca corrupção crê que é a Latina. | kõ ˈpokɐ kuʁupˈsɐ̃w̃ kɾe kjɛ ɐ lɐˈtinɐ | kũ ˈpokɐ kohup(i)ˈsɐ̃w̃ kɾe kjɛ a laˈtʃĩnɐ | With little corruption, believes that it is Latin.[41] |

Grammar

A notable aspect of the grammar of Portuguese is the verb. Morphologically, more verbal inflections from classical Latin have been preserved by Portuguese than by any other major Romance language. See Romance copula, for a detailed comparison. It has also some innovations not found in other Romance languages (except Galician and the Fala):

- The present perfect has an iterative sense unique to the Galician-Portuguese language group. It denotes an action or a series of actions that began in the past and are expected to keep repeating in the future. For instance, the sentence Tenho tentado falar com ela would be translated to "I have been trying to talk to her", not "I have tried to talk to her". On the other hand, the correct translation of the question "Have you heard the latest news?" is not *Tem ouvido a última notícia?, but Ouviu a última notícia?, since no repetition is implied.[42]

- The future subjunctive tense, which was developed by medieval West Iberian Romance, but has now fallen into disuse in Spanish and Galician, is still used in vernacular Portuguese. It appears in dependent clauses that denote a condition that must be fulfilled in the future, so that the independent clause will occur. English normally employs the present tense under the same circumstances:

- Se eu for eleito presidente, mudarei a lei.

- If I am elected president, I will change the law.

- Quando fores mais velho, vais entender.

- When you grow older, you will understand.

- The personal infinitive: infinitives can inflect according to their subject in person and number, often showing who is expected to perform a certain action; cf. É melhor voltares "It is better [for you] to go back", É melhor voltarmos "It is better [for us] to go back." Perhaps for this reason, infinitive clauses replace subjunctive clauses more often in Portuguese than in other Romance languages.

Writing system

| Portugal and non-1990 Agreement countries | Brazil and 1990 Agreement countries | translation |

|---|---|---|

| direcção | direção | direction |

| óptimo | ótimo | excellent, optimal |

Portuguese is written with 23 or 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, making use of five diacritics to denote stress, vowel height, contraction, nasalization, and other sound changes (acute accent, grave accent, circumflex accent, tilde, and cedilla). Accented characters and digraphs are not counted as separate letters for collation purposes.

Spelling reforms

See also

- Portuguese literature

- Portuguese poetry

- List of Portuguese language poets

- List of international organisations which have Portuguese as an official language

- Brazilian literature

- List of Brazilian poets

- Lusophone

- Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP)

- Instituto Camões

- International Portuguese Language Institute

- Museum of the Portuguese Language

- Portuñol

- Portuguese in the United States

Notes

- ↑ In this discussion of a politician woman from Alagoas state it is possible to notice that the "r" in this position is a voiceless glottal fricative http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKoGPP0ntz0

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (2005). "Portuguese". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=por. Retrieved 2008-10-15. "Population total all countries: 177,457,180"

- ↑ "Portuguese Language". Portuguese Language. Microsoft Corporation. 2008. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761564972/Portuguese_Language.html. Retrieved 2008-10-15. "about 221 million speakers".

- ↑ Lusa angency (2008). "Portuguese". http://www.brazzilmag.com/content/view/9689/1/. Retrieved 2009-01-15. "Portuguese Total 2008"

- ↑ "Somos 240 milhões de falantes" (in Portuguese). http://diario.iol.pt/sociedade/lingua-portuguesa-portugues-ensino-governo-alunos/972503-4071.html.

- ↑ "http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/cerv/12604733118045969643624/p0000009.htm". Cervantesvirtual.com. http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/cerv/12604733118045969643624/p0000009.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ 'Encyclopedia of Literature' Joseph T. Shipley; Philosophical Library, 1946. 1188 pgs.

- ↑ Prem Poddar, Rajeev S. Patke, Lars Jensen. A historical companion to postcolonial literatures: continental Europe and its empires. Edinburgh University Press, 2008. p. 531.

- ↑ "Uruguayan government makes Portuguese mandatory." (in Portuguese). 2007-11-05. http://noticias.uol.com.br/ultnot/lusa/2007/11/05/ult611u75523.jhtm. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ↑ "Portuguese will be mandatory in high school." (in Spanish). 2009-01-21. http://portal.educ.ar/noticias/educacion-y-sociedad/el-portugues-sera-materia-obli.php. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ↑ "Portuguese language will be option in the official Venezuelan teachings." (in Portuguese). 2009-05-24. http://www.letras.etc.br/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=93:lingua-portuguesa-sera-opcao-no-ensino-oficial-venezuelano&catid=6:noticia&Itemid=13/. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ↑ "Zambia will adopt the Portuguese language in their Basic school." (in Portuguese). 2009-05-26. http://movv.org/2009/05/26/a-zambia-vai-adotar-a-lingua-portuguesa-no-seu-ensino-basico/.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 "Congo will start to teach Portuguese in schools." (in Portuguese). 2010-06-04. http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/arteelazer,congo-passara-a-ensinar-portugues-nas-escolas,561666,0.htm/. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ↑ IBGE Official website

- ↑ INE Official website

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 CPLP Official website

- ↑ See the main article Geographic distribution of Portuguese, for references.

- ↑ Uruguay recently adopted Portuguese language in its education system as an obligatory subject http://noticias.uol.com.br/ultnot/lusa/2007/11/05/ult611u75523.jhtm

- ↑ "The Portuguese-Speaking Community in Australia". Radio.sbs.com.au. http://radio.sbs.com.au/language.php?page=info&language=Portuguese. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ JAPÃO: IMIGRANTES BRASILEIROS POPULARIZAM LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA

- ↑ "Where America's Other Languages Are Spoken". Proenglish.org. http://www.proenglish.org/issues/offeng/languagepercentages.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Widely spoken but 'minor'? Portuguese seeks respect

- ↑ Hispanic Reading Room of the U.S. Library of Congress website, Twentieth-Century Arrivals from Portugal Settle in Newark, New Jersey,

- ↑ "Brazucas (Brazilians living in New York)". Nyu.edu. http://www.nyu.edu/classes/blake.map2001/brazil.html. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Hispanic Reading Room of the U.S. Library of Congress website, Whaling, Fishing, and Industrial Employment in Southeastern New England

- ↑ "Portuguese Language in Goa". Colaco.net. http://www.colaco.net/1/port.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ "The Portuguese Experience: The Case of Goa, Daman and Diu". Rjmacau.com. http://www.rjmacau.com/english/rjm1996n3/ac-mary/portuguese.html. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Multicultural Canada

- ↑ "Bermuda". World InfoZone. http://www.worldinfozone.com/country.php?country=Bermuda. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ EUROPA website Languages in the EU

- ↑ "Obiang convierte al portugués en tercer idioma oficial para entrar en la Comunidad lusófona de Naciones", Terra. 13-07-2007

- ↑ From Audio samples of the dialects of Portuguese at the Instituto Camões website.

- ↑ Note: the speaker of this sound file is from Rio, and he is talking about his experience with Nordestino and Nortista accents.

- ↑ "Ethnologue". Ethnologue. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=glg. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Yves Camus, "Jesuits' Journeys in Chinese Studies"

- ↑ "Dicionário Português-Chinês : Pu Han ci dian : Portuguese-Chinese dictionary", by Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci; edited by John W. Witek. Published 2001, Biblioteca Nacional. ISBN 972-565-298-3. Partial preview available on Google Books

- ↑ "ONU: Petição para tornar português língua oficial". Diario.iol.pt. 2005-11-17. http://diario.iol.pt/noticia.html?id=611263&div_id=4071. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Português pode ser língua oficial na ONU

- ↑ http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portugu%C3%AAs_brasileiro

- ↑ Handbook of the International Phonetic Association pg. 126–130; the reference applies to the entire section

- ↑ White, Landeg. (1997). The Lusiads—English translation. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280151-1

- ↑ Squartini, Mario (1998) Verbal Periphrases in Romance—Aspect, Actionality, and Grammaticalization ISBN 3-11-016160-5

References

General

- História da Lingua Portuguesa Instituto Camões

- A Língua Portuguesa in Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil (...)

Literature

- Poesia e Prosa Medievais, by Maria Ema Tarracha Ferreira, Ulisseia 1998, 3rd ed., ISBN 978-972-568-124-4.

- Bases Temáticas—Língua Portuguesa in Instituto Camões

- Portuguese Literature in The Catholic Encyclopedia

Phonology, orthography and grammar

- International Phonetic Association (1999) Handbook of the International Phonetic Association ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- Mateus, Maria Helena & d'Andrade, Ernesto (2000) The Phonology of Portuguese ISBN 0-19-823581-X (Excerpt available at Google Books)

- Bergström, Magnus & Reis, Neves Prontuário Ortográfico Editorial Notícias, 2004.

- A pronúncia do português europeu—European Portuguese Pronunciation

- Dialects of Portuguese at the Instituto Camões

- Audio samples of the dialects of Portugal

- Audio samples of the dialects from outside Europe

Reference dictionaries

- Antônio Houaiss (2000), Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa (228,500 entries).

- Aurélio Buarque de Holanda Ferreira, Novo Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa (1809pp)

- English-Portuguese-Chinese Dictionary (Freeware for Windows/Linux/Mac)

Linguistic studies

- Lindley Cintra, Luís F. Nova Proposta de Classificação dos Dialectos Galego-Portugueses (PDF) Boletim de Filologia, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Filológicos, 1971.

External links

- Swadesh list in English and Portuguese

- Learn Portuguese BBC

- Portuguese Language Notes BBC

- AULP—Associação das Universidades de Língua Portuguesa Portuguese Language Universities Association.

- Portuguese in East Timor an interview with Dr. Geoffrey Hull.

- ABL—Academia Brasileira de letras (em português)—(Brazilian Academy of Letters) (Portuguese)

- Free Portuguese Online Dictionary

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||