Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

- This article is about the Roman statesman and general. For the personal name, see Agrippa (praenomen). For a list of individuals with this name, see Agrippa (disambiguation).

| Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa | |

|---|---|

| 63 BC – 12 BC | |

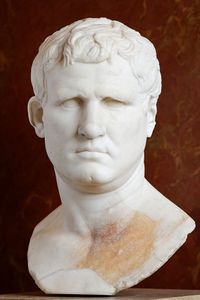

Bust of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa from the Louvre, Paris |

|

| Place of birth | Istria? Asisium? |

| Place of death | Campania |

| Allegiance | Roman Empire |

| Years of service | 45 BC – 12 BC |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held | Roman army |

| Battles/wars | Caesar's civil war Battle of Munda Battle of Mutina Battle of Philippi Battle of Actium |

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (c. 63 BC–12 BC) was a Roman statesman and general.[1] He was a close friend, son-in-law, lieutenant and defense minister to Octavian, the future emperor Caesar Augustus. He was responsible for most of Octavian’s military victories, most notably winning the naval Battle of Actium against the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII of Egypt.

He was the son-in-law of the Emperor Augustus, maternal grandfather of the Emperor Caligula, father-in-law of the Emperor Tiberius and the Emperor Claudius, and maternal great-grandfather of the Emperor Nero.

Contents |

Early life

Agrippa was born between 23 October and 23 November in 64–62 BC[2] in an uncertain location.[3] His father was perhaps called Lucius Vipsanius Agrippa. He had an elder brother whose name was also Lucius Vipsanius Agrippa, and a sister named Vipsania Polla. The family had not been prominent in Roman public life.[4] However, Agrippa was about the same age as Octavian (the future emperor Augustus), and the two were educated together and became close friends. Despite Agrippa's association with the family of Julius Caesar, his elder brother chose another side in the civil wars of the 40s BC, fighting under Cato against Caesar in Africa. When Cato's forces were defeated, Agrippa's brother was taken prisoner but freed after Octavian interceded on his behalf.[5]

It is not known whether Agrippa fought against his brother in Africa, but he probably served in Caesar's campaign of 46–45 BC against Gnaeus Pompeius, which culminated in the Battle of Munda.[6] Caesar regarded him highly enough to send him with Octavius in 45 BC to study in Apollonia with the Macedonian legions, while Caesar consolidated his power in Rome.[7] It was in the fourth month of their stay in Apollonia that the news of Julius Caesar's assassination in March 44 BC reached them. Despite the advice of Agrippa and another friend, Quintus Salvidienus Rufus, that he march on Rome with the troops from Macedonia, Octavius decided to sail to Italy with a small retinue. After his arrival, he learnt that Caesar had adopted him as his legal heir.[8] (Octavius now took over Caesar's name, but is referred to by modern historians as "Octavian" during this period.)

Rise in power

After Octavian's return to Rome, he and his supporters realized they needed the support of legions. Agrippa helped Octavian to levy troops in Campania.[9] Once Octavian had his legions, he made a pact with Mark Antony and Lepidus, legally established in 43 BC as the Second Triumvirate. Octavian and his consular colleague Quintus Pedius arranged for Caesar's assassins to be prosecuted in their absence, and Agrippa was entrusted with the case against Gaius Cassius Longinus.[10] It may have been in the same year that Agrippa began his political career, holding the position of Tribune of the Plebs, which granted him entry to the Senate.[11]

In 42 BC, Agrippa probably fought alongside Octavian and Antony in the Battle of Philippi.[12] After their return to Rome, he played a major role in Octavian's war against Lucius Antonius and Fulvia Antonia, respectively the brother and wife of Mark Antony, which began in 41 BC and ended in the capture of Perusia in 40 BC. However, Salvidienus remained Octavian's main general at this time.[13] After the Perusine war, Octavian departed for Gaul, leaving Agrippa as urban praetor in Rome with instructions to defend Italy against Sextus Pompeius, an opponent of the Triumvirate who was now occupying Sicily. In July 40, while Agrippa was occupied with the Ludi Apollinares that were the praetor's responsibility, Sextus began a raid in southern Italy. Agrippa advanced on him, forcing him to withdraw.[14] However, the Triumvirate proved unstable, and in August 40 both Sextus and Antony invaded Italy (but not in an organized alliance). Agrippa's success in retaking Sipontum from Antony helped bring an end to the conflict.[15] Agrippa was among the intermediaries through whom Antony and Octavian agreed once more upon peace. During the discussions Octavian learned that Salvidienus had offered to betray him to Antony, with the result that Salvidienus was prosecuted and either executed or committed suicide. Agrippa was now Octavian's leading general.[16]

In 39 or 38 BC, Octavian appointed Agrippa governor of Transalpine Gaul, where in 38 he put down a rising of the Aquitanians. He also fought the Germanic tribes, becoming the next Roman general to cross the Rhine after Julius Caesar. He was summoned back to Rome by Octavian to assume the consulship for 37 BC. He was well below the usual minimum age of 43, but Octavian had suffered a humiliating naval defeat against Sextus Pompey and needed his friend to oversee the preparations for further warfare. Agrippa refused the offer of a triumph for his exploits in Gaul – on the grounds, says Dio, that he thought it improper to celebrate during a time of trouble for Octavian.[17] Since Sextus Pompeius had command of the sea on the coasts of Italy, Agrippa's first care was to provide a safe harbor for his ships. He accomplished this by cutting through the strips of land which separated the Lacus Lucrinus from the sea, thus forming an outer harbor, while joining the lake Avernus to the Lucrinus to serve as an inner harbor.[18] The new harbor-complex was named Portus Julius in Octavian's honour.[19] Agrippa was also responsible for technological improvements, including larger ships and an improved form of grappling hook.[20] About this time, he married Caecilia Pomponia Attica, daughter of Cicero's friend Titus Pomponius Atticus.[21]

In 36 BC Octavian and Agrippa set sail against Sextus. The fleet was badly damaged by storms and had to withdraw; Agrippa was left in charge of the second attempt. Thanks to superior technology and training, Agrippa and his men won decisive victories at Mylae and Naulochus, destroying all but seventeen of Sextus' ships and compelling most of his forces to surrender. Octavian, with his power increased, forced the triumvir Lepidus into retirement and entered Rome in triumph.[22] Agrippa received the unprecedented honor of a naval crown decorated with the beaks of ships; as Dio remarks, this was "a decoration given to nobody before or since".[23]

Life in public service

Agrippa participated in smaller military campaigns in 35 and 34 BC, but by the autumn of 34 he had returned to Rome.[24] He rapidly set out on a campaign of public repairs and improvements, including renovation of the aqueduct known as the Aqua Marcia and an extension of its pipes to cover more of the city. Through his actions after being elected in 33 BC as one of the aediles (officials responsible for Rome's buildings and festivals), the streets were repaired and the sewers were cleaned out, while lavish public spectacles were put on.[25] Agrippa signalized his tenure of office by effecting great improvements in the city of Rome, restoring and building aqueducts, enlarging and cleansing the Cloaca Maxima, constructing baths and porticos, and laying out gardens. He also gave a stimulus to the public exhibition of works of art. It was unusual for an ex-consul to hold the lower-ranking position of aedile,[26] but Agrippa's success bore out this break with tradition. As emperor, Augustus would later boast that "he had found the city of brick but left it of marble", thanks in part to the great services provided by Agrippa under his reign.

Agrippa's father-in-law Atticus, suffering from a serious illness, committed suicide in 32 BC. According to Atticus' friend and biographer Cornelius Nepos, this decision was a cause of serious grief to Agrippa.[27]

Antony and Cleopatra

Agrippa was again called away to take command of the fleet when the war with Antony and Cleopatra broke out. He captured the strategically important city of Methone at the southwest of the Peloponnese, then sailed north, raiding the Greek coast and capturing Corcyra (modern Corfu). Octavian then brought his forces to Corcyra, occupying it as a naval base.[28] Antony drew up his ships and troops at Actium, where Octavian moved to meet him. Agrippa meanwhile defeated Antony's supporter Quintus Nasidius in a naval battle at Patrae.[29] Dio relates that as Agrippa moved to join Octavian near Actium, he encountered Gaius Sosius, one of Antony's lieutenants, who was making a surprise attack on the squadron of Lucius Tarius, a supporter of Octavian. Agrippa's unexpected arrival turned the battle around.[30]

As the decisive battle approached, according to Dio, Octavian received intelligence that Antony and Cleopatra planned to break past his naval blockade and escape. At first he wished to allow the flagships past, arguing that he could overtake them with his lighter vessels and that the other opposing ships would surrender when they saw their leaders' cowardice. Agrippa objected that Antony's ships, although larger, could outrun Octavian's if they hoisted sails, and that Octavian ought to fight now because Antony's fleet had just been struck by storms. Octavian followed his friend's advice.[31]

On September 2 31 BC, the Battle of Actium was fought. Octavian's victory, which gave him the mastery of Rome and the empire, was mainly due to Agrippa.[32] As a token of signal regard, Octavian bestowed upon him the hand of his niece Claudia Marcella Major in 28 BC. He also served a second consulship with Octavian the same year. In 27 BC, Agrippa held a third consulship with Octavian, and in that year, the senate also bestowed upon Octavian the imperial title of Augustus.

In commemoration of the Battle of Actium, Agrippa built and dedicated the building that served as the Roman Pantheon before its destruction in 80. Emperor Hadrian used Agrippa's design to build his own Pantheon, which survives in Rome. The inscription of the later building, which was built around 125, preserves the text of the inscription from Agrippa's building during his third consulship. The years following his third consulship, Agrippa spent in Gaul, reforming the provincial administration and taxation system, along with building an effective road system and aqueducts.

Late life

His friendship with Augustus seems to have been clouded by the jealousy of his brother-in-law Marcus Claudius Marcellus, which was probably fomented by the intrigues of Livia, the third wife of Augustus, who feared his influence over her husband. Traditionally it is said the result of such jealousy was that Agrippa left Rome, ostensibly to take over the governorship of eastern provinces - a sort of honorable exile, but, he only sent his legate to Syria, while he himself remained at Lesbos and governed by proxy, though he may have been on a secret mission to negotiate with the Parthians about the return of the Roman legions standards which they held.[33] On the death of Marcellus, which took place within a year of his exile, he was recalled to Rome by Augustus, who found he could not dispense with his services. However, if one places the events in the context of the crisis in 23 BC it seems unlikely that, when facing significant opposition and about to make a major political climb down, the emperor Augustus would place a man in exile in charge of the largest body of Roman troops. What is far more likely is that Agrippa's 'exile' was actually the careful political positioning of a loyal lieutenant in command of a significant army as a backup plan in case the settlement plans of 23 BC failed and Augustus needed military support.

It is said that Maecenas advised Augustus to attach Agrippa still more closely to him by making him his son-in-law. He accordingly induced him to divorce Marcella and marry his daughter Julia the Elder by 21 BC, the widow of the late Marcellus, equally celebrated for her beauty, abilities, and her shameless profligacy. In 19 BC, Agrippa was employed in putting down a rising of the Cantabrians in Hispania (Cantabrian Wars). He was appointed governor of the eastern provinces a second time in 17 BC, where his just and prudent administration won him the respect and good-will of the provincials, especially from the Jewish population. Agrippa also restored effective Roman control over the Cimmerian Chersonnese (modern-day Crimea) during his governorship.

Agrippa’s last public service was his beginning of the conquest of the upper Danube River region, which would become the Roman province of Pannonia in 13 BC. He died at Campania in 12 March of 12 BC at the age of 51. His posthumous son, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa Postumus, was named in his honor. Augustus honored his memory by a magnificent funeral and spent over a month in mourning. Augustus personally oversaw all of Agrippa's children’s educations. Although Agrippa had built a tomb for himself, Augustus had Agrippa's remains placed in Augustus' own mausoleum, according to Dio 54.28.5.

Legacy

Agrippa was also known as a writer, especially on the subject of geography. Under his supervision, Julius Caesar's dream of having a complete survey of the empire made was carried out. He constructed a circular chart, which was later engraved on marble by Augustus, and afterwards placed in the colonnade built by his sister Polla. Amongst his writings, an autobiography, now lost, is referred to.

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, along with Gaius Maecenas and Octavian, was a central person in the establishing of the Principate system of emperors, which would govern the Roman Empire up until the Crisis of the Third Century and the birth of Dominate system. His grandson Gaius is known to history as the Emperor Caligula, and his great-grandson Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus would rule as the Emperor Nero.

Marriages and issue

Agrippa had several children through his three marriages:

- By his first wife, Caecilia Attica, he had a daughter, Vipsania Agrippina, who was to be the first wife of the Emperor Tiberius, and who gave birth to a son, Drusus the Younger.

- By his second wife, Claudia Marcella Major, he had a daughter, whose name remains unknown, but likely might have been "Vipsania Marcella"

- By his third wife, Julia the Elder (daughter of Augustus), he had five children: Gaius Caesar, Julia the Younger, Lucius Caesar, Agrippina the Elder (wife of Germanicus, mother of the Emperor Caligula and Empress Agrippina the Younger), and Agrippa Postumus (a posthumous son).

Descendants

Through his numerous children, Agrippa would become ancestor to many subsequent members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, whose position he helped to attain, as well as many other reputed Romans.

- 1. Vipsania Agrippina, 36 BC-20 AD, had 8 children

- A. Drusus Julius Caesar, 13 BC-23 AD, had 3 children

- I. Julia, 5 AD-43 AD, had 4 children

- II. Tiberius Julius Caesar Nero Gemellus, 19 AD-37 AD or 38 AD, died without issue

- III. Tiberius Claudius Caesar Germanicus II Gemellus, 19 AD-23 AD, died young

- B. Gaius Asinius Polio, died 45 AD, had three children[36]

- I. Asinia Pollionis filia[37]

- II. Gaius Asinius Placentinus, born 25 AD, had 1 child

- a. Marcus Asinius Pollio Verrucosus (consul in 81 AD), 45 AD or 50 AD – after 81 AD

- III. Marcus Asinius Pollio, born 30 AD, had 1 child

- a. Marcus Asinius Atratinus (consul in 89 AD), 55 AD – after 89 AD

- C. Marcus Asinius Agrippa, died 26 AD, had 1 child

- I. Marcus Asinius Marcellus, had 1 child[38]

- a. Marcus Asinius Marcellus (consul in 104 AD)

- I. Marcus Asinius Marcellus, had 1 child[38]

- D. Gnaeus Asinius Saloninus, died 22 AD

- E. Servius Asinius Celer[39][40], died before mid-47 AD, had 1 child

- a. Asinia Agrippina

- F. Lucius Asinius Gallus[41]

- G. Gnaeus Asinius[42]

- H. Asinia, had 1 child

- a. Pomponia Graecina, had 1 child

- i. Aulus Plautius, died without issue (murdered by Emperor Nero)

- a. Pomponia Graecina, had 1 child

- A. Drusus Julius Caesar, 13 BC-23 AD, had 3 children

- 2. Vipsania Marcella, born 27 BC, possibly had 1 child

- A. a son[43]

- 3. Gaius Caesar, 20 BC – 4 AD, died without issue

- 4. Julia the Younger, 19 BC – 28 AD, had 2 children

- A. Aemilia Lepida (fiancee of Claudius), 4 BC – 53 AD, had 5 children

- I. Marcus Junius Silanus Torquatus, 14 AD – 54 AD, had 1 child

- a. Lucius Junius Silanus Torquatus the younger, 50 – 66, died young

- II. Junia Calvina, 15 AD – 79 AD, died without issue

- III. Decimus Junius Silanus Torquatus, died 64 AD without issue

- IV. Lucius Junius Silanus Torquatus the elder, d. 49 without issue

- V. Junia Lepida, c. 18 AD – 65 AD, had 2 children

- a. Cassia Longina, c. 35 AD – ?, had 2 children

- i. Domitia Corbula, had 1 child

- i. unknown son

- ii. Domitia Longina, c. 53 AD – 130 AD, wife of Domitian

- i. Domitia Corbula, had 1 child

- b. Cassius Lepidus, born c. 55 AD, 1 child

- i. Cassia Lepida, born c. 80 AD; had 1 child

- i. Julia Cassia Alexandria, had 1 child

- i. Gaius Avidius Cassius, c. 130 AD – 175 AD; had 4 children

- i. Avidius Heliodorus

- ii. Avidius Maecianus

- iii. Avidia Alexandria

- iv. Volusia Laodice, born c. 165 AD, had 1 child[44]

- i. Tineia, born c. 195 AD, had 1 child

- i. Lucius Clodius Tineius Pupienus Bassus, c. 220 AD – aft. 250 AD, had 1 child

- i. Marcus Tineius Ovinius Castus Pulcher, b. 240 AD

- i. Lucius Clodius Tineius Pupienus Bassus, c. 220 AD – aft. 250 AD, had 1 child

- i. Tineia, born c. 195 AD, had 1 child

- i. Gaius Avidius Cassius, c. 130 AD – 175 AD; had 4 children

- i. Julia Cassia Alexandria, had 1 child

- i. Cassia Lepida, born c. 80 AD; had 1 child

- a. Cassia Longina, c. 35 AD – ?, had 2 children

- I. Marcus Junius Silanus Torquatus, 14 AD – 54 AD, had 1 child

- B. Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, 6 AD – 39 AD, died without issue

- A. Aemilia Lepida (fiancee of Claudius), 4 BC – 53 AD, had 5 children

- 5. Lucius Caesar, 17 BC – 2 AD, died without issue

- 6. Agrippina the Elder, 14 BC – 33 AD, had 6 children

- A. Nero Caesar, 6 AD - 30 AD, died without issue

- B. Drusus Caesar, 7 AD - 33 AD, died without issue

- C. Caligula, 12 AD - 41 AD, had 1 child

- I. Julia Drusilla, 39 AD - 41 AD, died young

- D. Agrippina the Younger, 15 AD - 59 AD, had 1 child

- I. Nero, 37 AD - 68 AD, had 1 child

- a. Claudia Augusta, 63 AD - 63 AD, died young

- I. Nero, 37 AD - 68 AD, had 1 child

- E. Julia Drusilla, 16 AD - 38 AD, died without issue

- F. Julia Livilla, 18 AD - 42 AD, died without issue

- 7. Agrippa Postumus, 12 BC – 14 AD, died without issue

Agrippa in popular culture

Drama

Marcus Agrippa, a highly fictionalised character based on Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa's early life, is part of the BBC-HBO-RAI television series Rome. He is played by Allen Leech. The series creates a romantic relationship between Agrippa and Octavian's sister Octavia Minor, for which there is no historical evidence.

A fictionalised version of Agrippa in his later life played a prominent role in the celebrated 1976 BBC Television series I, Claudius. Agrippa was portrayed as a much older man, though he would have only been 39 years old at the time of the first episode (24/23 BC). He was played by John Paul. Agrippa is also one of the principal characters in the British/Italian joint project Imperium: Augustus featuring flashbacks between Augustus and Julia about Agrippa, which shows him in his youth on serving in Caesar's army up until his victory at Actium and the defeat of Cleopatra. He is portrayed by Ken Duken.

Agrippa appears in several of the Cleopatra films. He is normally portrayed as an old man rather than a young one. Among the people to portray him are Philip Locke, Alan Rowe and Andrew Keir.

Literature

Agrippa is a character in William Shakespeare's play Antony and Cleopatra and also a main character in the early part of Robert Graves novel I, Claudius. He is a main character in the later two novels of Colleen McCullough's Masters of Rome series. He is also a featured character of prominence and importance in the historical fiction novel Cleopatra's Daughter by Michelle Moran.

See also

- Julio-Claudian family tree

Notes

- ↑ Plate, William (1867). "Agrippa, Marcus Vipsanius". In Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 77–80. http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-bio/0086.html

- ↑ Dio 54.28.3 places Agrippa's death in late March of 12 BC, while Pliny the Elder 7.46 states that he died "in his fifty-first year". Depending on whether Pliny meant that Agrippa was aged 50 or 51 at his death, this gives a date of birth between March 64 and March 62. A calendar from Cyprus or Syria includes a month named after Agrippa beginning on November 1, which may reflect the month of his birth. See Reinhold, pp. 2–4; Roddaz, pp. 23–26.

- ↑ Reinhold, p. 9; Roddaz, p. 23.

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus 2.96, 127.

- ↑ Nicolaus of Damascus, Life of Augustus 7.

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Augustus 94.12.

- ↑ Nicolaus of Damascus, Life of Augustus 16–17; Velleius Paterculus 2.59.5.

- ↑ Nicolaus of Damascus, Life of Augustus 31. It has been speculated that Agrippa was among the negotiators who won over Antony's Macedonian legions to Octavian, but there is no direct evidence for this; see Reinhold, p. 16.

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus 2.69.5; Plutarch, Life of Brutus 27.4.

- ↑ Mentioned only by Servius auctus on Virgil, Aeneid 8.682, but a necessary preliminary to his position as urban praetor in 40 BC. Roddaz (p. 41) favours the 43 BC date.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder 7.148 cites him as an authority for Octavian's illness on the occasion.

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 17–20.

- ↑ Dio 48.20; Reinhold, p. 22.

- ↑ Dio 48.28; Reinhold, p. 23.

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Dio 48.49; Reinhold, pp. 25–29. Agrippa's youth is noted by Lendering, "From Philippi to Actium".

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 29–32.

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Augustus 16.1.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 2.106, 118–119; Reinhold, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 37–42.

- ↑ Dio 49.14.3.

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Dio 49.42–43.

- ↑ Lendering, "From Philippi to Actium".

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos, Life of Atticus 21–22.

- ↑ Orosius, History Against the Pagans 6.19.6–7; Dio 50.11.1–12.3; Reinhold, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Dio 50.13.5.

- ↑ Dio 50.14.1–2; cf. Velleius Paterculus 2.84.2 ("Agrippa ... before the final conflict had twice defeated the fleet of the enemy"). Dio is wrong to say that Sosius was killed, since he in fact fought at and survived the Battle of Actium (Reinhold, p. 54 n. 14; Roddaz, p. 163 n. 140).

- ↑ Dio 50.31.1–3.

- ↑ Reinhold, pp. 57–58; Roddaz, pp. 178–181.

- ↑ David Magie, The Mission of Agrippa to the Orient in 23 BC, Classical Philology, Vol. 3, No. 2(Apr., 1908), pp. 145-152

- ↑ Their names are unknown, but it is known that all of them were killed by Nero, thus descent from this line is extinct

- ↑ Sir Ronald Syme claims that Sergius Octavius Laenas Pontianus, consul in 131 under Emperor Hadrian, set up a dedication to his grandmother, Rubellia Bassa.

- ↑ Gaius Asinius M.f. Tucurianus, Proconsul in Sardinia]] c. 115, was also supposedly one of his descendants, although through which line is unclear.

- ↑ Mentioned on an inscription from Tusculum

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals XII.64 and XIV.40

- ↑ Consul suffectus in 38 AD

- ↑ Seneca, The Pumpkinification of Claudius

- ↑ Cassius Dio (60.27.5)

- ↑ Mentioned in the records of the townsfolk of Puteoli, to whom he was a patron

- ↑ ^ a b R. Syme, The Augustan Aristocraty, Oxford, 1986, p. 125.

- ↑ http://wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=bernd-jansen&id=I34858

References

- Lendering, Jona. "Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa". Livius. http://www.livius.org/vi-vr/vipsanius/agrippa.html. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- Metello, Manuel Dejante Pinto de Magalhães Arnao; and João Carlos Metello de Nápoles (1998) (in Portuguese). Metellos de Portugal, Brasil e Roma. Lisboa: Edição Nova Arrancada. ISBN 9728369182.

- Reinhold, Meyer (1933). Marcus Agrippa: A Biography. Geneva: W. F. Humphrey Press.

- Roddaz, Jean-Michel (1984) (in French). Marcus Agrippa. Rome: École Française de Rome. ISBN 2-7283-0000-0.

Further reading

- Geoffrey Mottershead, The Constructions of Marcus Agrippa in the West, University of Melbourne, 2005

- Augustus' Funeral Oration for Agrippa

- Marcus Agrippa, article in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

| Preceded by Appius Claudius Pulcher and Gaius Norbanus Flaccus |

Consul of the Roman Republic with Lucius Caninius Gallus 37 BC |

Succeeded by Marcus Cocceius Nerva and Lucius Gellius Publicola |

| Preceded by Augustus and Sextus Appuleius |

Consul of the Roman Empire with Augustus 28 BC - 27 BC |

Succeeded by Augustus and Titus Statilius Taurus |