Acid

| Acids and bases |

|---|

| Acid dissociation constant Acid-base extraction Acid-base reaction Dissociation constant Acidity function Buffer solutions pH Proton affinity Self-ionization of water |

| Acid types |

| Brønsted · Lewis · Mineral Organic · Strong Superacids · Weak |

| Base types |

| Brønsted · Lewis · Organic Strong · Superbases Non-nucleophilic · Weak |

An acid (from the Latin acidus/acēre meaning sour[1]) in common usage is a substance that tastes sour, reacts with metals and carbonates, turns blue litmus paper red, and has a pH less than 7.0 in its standard state. Examples include acetic acid (in vinegar) and sulfuric acid (used in car batteries). Acid/base reactions differ from redox reactions in that there is no change in oxidation state. Acids can occur in solid, liquid or gaseous form, depending on the temperature. They can exist as pure substances or in solution. Chemicals or substances having the property of an acid are said to be acidic.

Contents |

Definitions and concepts

Modern definitions are concerned with the fundamental chemical reactions common to all acids.

Arrhenius acids

The Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius attributed the properties of acidity to hydrogen in 1884. An Arrhenius acid is a substance that increases the concentration of the hydronium ion, H3O+, when dissolved in water. This definition stems from the equilibrium dissociation of water into hydronium and hydroxide (OH−) ions:[2]

- H2O(l) + H2O(l)

H3O+(aq) + OH−(aq)

H3O+(aq) + OH−(aq)

In pure water the majority of molecules exist as H2O, but a small number of molecules are constantly dissociating and re-associating. Pure water is neutral with respect to acidity or basicity because the concentration of hydroxide ions is always equal to the concentration of hydronium ions. An Arrhenius base is a molecule which increases the concentration of the hydroxide ion when dissolved in water. Note that chemists often write H+(aq) and refer to the hydrogen ion when describing acid-base reactions but the free hydrogen nucleus, a proton, does not exist alone in water, it exists as the hydronium ion, H3O+.

Brønsted acids

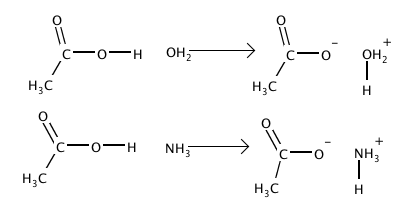

While the Arrhenius concept is useful for describing many reactions, it is also quite limited in its scope. In 1923 chemists Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and Thomas Martin Lowry independently recognized that acid-base reactions involve the transfer of a proton. A Brønsted-Lowry acid (or simply Brønsted acid) is a species that donates a proton to a Brønsted-Lowry base.[2] Brønsted-Lowry acid-base theory has several advantages over Arrhenius theory. Consider the following reactions of acetic acid (CH3COOH), the organic acid that gives vinegar its characteristic taste:

Both theories easily describe the first reaction: CH3COOH acts as an Arrhenius acid because it acts as a source of H3O+ when dissolved in water, and it acts as a Brønsted acid by donating a proton to water. In the second example CH3COOH undergoes the same transformation, in this case donating a proton to ammonia (NH3), but cannot be described using the Arrhenius definition of an acid because the reaction does not produce hydronium. Brønsted-Lowry theory can also be used to describe molecular compounds, whereas Arrhenius acids must be ionic compounds. Hydrogen chloride (HCl) and ammonia combine under several different conditions to form ammonium chloride, NH4Cl. In aqueous solution HCl behaves as hydrochloric acid and exists as hydronium and chloride ions. The following reactions illustrate the limitations of Arrhenius's definition:

- 1.) H3O+(aq) + Cl−(aq) + NH3 → Cl−(aq) + NH4+(aq)

- 2.) HCl(benzene) + NH3(benzene) → NH4Cl(s)

- 3.) HCl(g) + NH3(g) → NH4Cl(s)

As with the acetic acid reactions, both definitions work for the first example, where water is the solvent and hydronium ion is formed. The next two reactions do not involve the formation of ions but are still proton transfer reactions. In the second reaction hydrogen chloride and ammonia (dissolved in benzene) react to form solid ammonium chloride in a benzene solvent and in the third gaseous HCl and NH3 combine to form the solid.

Lewis acids

A third concept was proposed by Gilbert N. Lewis which includes reactions with acid-base characteristics that do not involve a proton transfer. A Lewis acid is a species that accepts a pair of electrons from another species; in other words, it is an electron pair acceptor.[2] Brønsted acid-base reactions are proton transfer reactions while Lewis acid-base reactions are electron pair transfers. All Brønsted acids are also Lewis acids, but not all Lewis acids are Brønsted acids. Contrast the following reactions which could be described in terms of acid-base chemistry.

In the first reaction a fluoride ion, F−, gives up an electron pair to boron trifluoride to form the product tetrafluoroborate. Fluoride "loses" a pair of valence electrons because the electrons shared in the B—F bond are located in the region of space between the two atomic nuclei and are therefore more distant from the fluoride nucleus than they are in the lone fluoride ion. BF3 is a Lewis acid because it accepts the electron pair from fluoride. This reaction cannot be described in terms of Brønsted theory because there is no proton transfer. The second reaction can be described using either theory. A proton is transferred from an unspecified Brønsted acid to ammonia, a Brønsted base; alternatively, ammonia acts as a Lewis base and transfers a lone pair of electrons to form a bond with a hydrogen ion. The species that gains the electron pair is the Lewis acid; for example, the oxygen atom in H3O+ gains a pair of electrons when one of the H—O bonds is broken and the electrons shared in the bond become localized on oxygen. Depending on the context, a Lewis acid may also be described as an oxidizer or an electrophile.

The Brønsted-Lowry definition is the most widely used definition; unless otherwise specified acid-base reactions are assumed to involve the transfer of a proton (H+) from an acid to a base.

Dissociation and equilibrium

Reactions of acids are often generalized in the form HA ![]() H+ + A−, where HA represents the acid and A− is the conjugate base. Acid-base conjugate pairs differ by one proton, and can be interconverted by the addition or removal of a proton (protonation and deprotonation, respectively). Note that the acid can be the charged species and the conjugate base can be neutral in which case the generalized reaction scheme could be written as HA+

H+ + A−, where HA represents the acid and A− is the conjugate base. Acid-base conjugate pairs differ by one proton, and can be interconverted by the addition or removal of a proton (protonation and deprotonation, respectively). Note that the acid can be the charged species and the conjugate base can be neutral in which case the generalized reaction scheme could be written as HA+ ![]() H+ + A. In solution there exists an equilibrium between the acid and its conjugate base. The equilibrium constant K is an expression of the equilibrium concentrations of the molecules or the ions in solution. Brackets indicate concentration, such that [H2O] means the concentration of H2O. The acid dissociation constant Ka is generally used in the context of acid-base reactions. The numerical value of Ka is equal to the concentration of the products divided by the concentration of the reactants, where the reactant is the acid (HA) and the products are the conjugate base and H+.

H+ + A. In solution there exists an equilibrium between the acid and its conjugate base. The equilibrium constant K is an expression of the equilibrium concentrations of the molecules or the ions in solution. Brackets indicate concentration, such that [H2O] means the concentration of H2O. The acid dissociation constant Ka is generally used in the context of acid-base reactions. The numerical value of Ka is equal to the concentration of the products divided by the concentration of the reactants, where the reactant is the acid (HA) and the products are the conjugate base and H+.

The stronger of two acids will have a higher Ka than the weaker acid; the ratio of hydrogen ions to acid will be higher for the stronger acid as the stronger acid has a greater tendency to lose its proton. Because the range of possible values for Ka spans many orders of magnitude, a more manageable constant, pKa is more frequently used, where pKa = -log10 Ka. Stronger acids have a smaller pKa than weaker acids. Experimentally determined pKa at 25°C in aqueous solution are often quoted in textbooks and reference material.

Nomenclature

In the classical naming system, acids are named according to their anions. That ionic suffix is dropped and replaced with a new suffix (and sometimes prefix), according to the table below. For example, HCl has chloride as its anion, so the -ide suffix makes it take the form hydrochloric acid. In the IUPAC naming system, "aqueous" is simply added to the name of the ionic compound. Thus, for hydrogen chloride, the IUPAC name would be aqueous hydrogen chloride. The prefix "hydro-" is added only if the acid is made up of just hydrogen and one other element.

Classical naming system:

| Anion prefix | Anion suffix | Acid prefix | Acid suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| per | ate | per | ic acid | perchloric acid (HClO4) |

| ate | ic acid | chloric acid (HClO3) | ||

| ite | ous acid | chlorous acid (HClO2) | ||

| hypo | ite | hypo | ous acid | hypochlorous acid (HClO) |

| ide | hydro | ic acid | hydrochloric acid (HCl) |

Acid strength

The strength of an acid refers to its ability or tendency to lose a proton. A strong acid is one that completely dissociates in water; in other words, one mole of a strong acid HA dissolves in water yielding one mole of H+ and one mole of the conjugate base, A−, and none of the protonated acid HA. In contrast a weak acid only partially dissociates and at equilibrium both the acid and the conjugate base are in solution. Examples of strong acids are hydrochloric acid (HCl), hydroiodic acid (HI), hydrobromic acid (HBr), perchloric acid (HClO4), nitric acid (HNO3) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4). In water each of these essentially ionizes 100%. The stronger an acid is, the more easily it loses a proton, H+. Two key factors that contribute to the ease of deprotonation are the polarity of the H—A bond and the size of atom A, which determines the strength of the H—A bond. Acid strengths are also often discussed in terms of the stability of the conjugate base.

Stronger acids have a higher Ka and a lower pKa than weaker acids.

Sulfonic acids, which are organic oxyacids, are a class of strong acids. A common example is toluenesulfonic acid (tosylic acid). Unlike sulfuric acid itself, sulfonic acids can be solids. In fact, polystyrene functionalized into polystyrene sulfonate is a solid strongly acidic plastic that is filterable.

Superacids are acids stronger than 100% sulfuric acid. Examples of superacids are fluoroantimonic acid, magic acid and perchloric acid. Superacids can permanently protonate water to give ionic, crystalline hydronium "salts". They can also quantitatively stabilize carbocations.

Polarity and the inductive effect

Polarity refers to the distribution of electrons in a bond, the region of space between two atomic nuclei where a pair of electrons is shared. When two atoms have roughly the same electronegativity (ability to attract electrons) the electrons are shared evenly and spend equal time on either end of the bond. When there is a significant difference in electronegativities of two bonded atoms, the electrons spend more time near the nucleus of the more electronegative element and an electrical dipole, or separation of charges, occurs, such that there is a partial negative charge localized on the electronegative element and a partial positive charge on the electropositive element. Hydrogen is an electropositive element and accumulates a slightly positive charge when it is bonded to an electronegative element such as oxygen or bromine. As the electron density on hydrogen decreases it is more easily abstracted, in other words, it is more acidic. Moving from left to right across a row on the periodic table elements become more electronegative (excluding the noble gases), and the strength of the binary acid formed by the element increases accordingly:

| Formula | Name | pKa[3] |

|---|---|---|

| HF | hydrofluoric acid | 3.17 |

| H2O | water | 15.7 |

| NH3 | ammonia | 38 |

| CH4 | methane | 48 |

The electronegative element need not be directly bonded to the acidic hydrogen to increase its acidity. An electronegative atom can pull electron density out of an acidic bond through the inductive effect. The electron-withdrawing ability diminishes quickly as the electronegative atom moves away from the acidic bond. The effect is illustrated by the following series of halogenated butanoic acids. Chlorine is more electronegative than bromine and therefore has a stronger effect. The hydrogen atom bonded to the oxygen is the acidic hydrogen. Butanoic acid is a carboxylic acid.

| Structure | Name | pKa[4] |

|---|---|---|

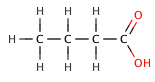

|

butanoic acid | ≈4.8 |

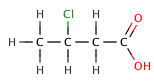

|

4-chlorobutanoic acid | 4.5 |

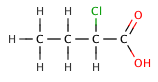

|

3-chlorobutanoic acid | ≈4.0 |

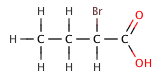

|

2-bromobutanoic acid | 2.93 |

|

2-chlorobutanoic acid | 2.86 |

As the chlorine atom moves further away from the acidic O—H bond, its effect diminishes. When the chlorine atom is just one carbon removed from the carboxylic acid group the acidity of the compound increases significantly, compared to butanoic acid (a.k.a. butyric acid). However, when the chlorine atom is separated by several bonds the effect is much smaller. Bromine is much more electronegative than either carbon or hydrogen, but not as electronegative as chlorine, so the pKa of 2-bromobutanoic acid is slightly greater than the pKa of 2-chlorobutanoic acid.

The number of electronegative atoms adjacent an acidic bond also affects acid strength. Oxoacids have the general formula HOX where X can be any atom and may or may not share bonds to other atoms. Increasing the number of electronegative atoms or groups on atom X decreases the electron density in the acidic bond, making the loss of the proton easier. Perchloric acid is a very strong acid (pKa ≈ -8) and completely dissociates in water. Its chemical formula is HClO4 and it comprises a central chlorine atom with three chlorine-oxygen double bonds (Cl=O) and one chlorine-oxygen single bond (Cl—O). The singly bonded oxygen bears an extremely acidic hydrogen atom which is easily abstracted. In contrast, chloric acid (HClO3) is a weaker acid, though still quite strong (pKa = -1.0), while chlorous acid (HClO2, pKa = +2.0) and hypochlorous acid (HClO, pKa = +7.53) acids are weak acids.[5]

Carboxylic acids are organic acids that contain an acidic hydroxyl group and a carbonyl (C=O bond). Carboxylic acids can be reduced to the corresponding alcohol; the replacement of an electronegative oxygen atom with two electropositive hydrogens yields a product which is essentially non-acidic. The reduction of acetic acid to ethanol using LiAlH4 (lithium aluminium hydride or LAH) and ether is an example of such a reaction.

The pKa for ethanol is 16, compared to 4.76 for acetic acid.[4][6]

Atomic radius and bond strength

Another factor that contributes to the ability of an acid to lose a proton is the strength of the bond between the acidic hydrogen and the atom that bears it. This, in turn, is dependent on the size of the atoms sharing the bond. For an acid HA, as the size of atom A increases, the strength of the bond decreases, meaning that it is more easily broken, and the strength of the acid increases. Bond strength is a measure of how much energy it takes to break a bond. In other words, it takes less energy to break the bond as atom A grows larger, and the proton is more easily removed by a base. This partially explains why hydrofluoric acid is considered a weak acid while the other hydrohalic acids (HCl, HBr, HI) are strong acids. Although fluorine is more electronegative than the other halogens, its atomic radius is also much smaller, so it shares a stronger bond with hydrogen. Moving down a column on the periodic table atoms become less electronegative but also significantly larger, and the size of the atom tends to dominate its acidity when sharing a bond to hydrogen. Hydrogen sulfide, H2S, is a stronger acid than water, even though oxygen is more electronegative than sulfur. Just as with the halogens, this is because sulfur is larger than oxygen and the H—S bond is more easily broken than the H—O bond.

Chemical characteristics

Monoprotic acids

Monoprotic acids are those acids that are able to donate one proton per molecule during the process of dissociation (sometimes called ionization) as shown below (symbolized by HA):

-

-

-

-

- HA(aq) + H2O(l)

H3O+(aq) + A−(aq) Ka

H3O+(aq) + A−(aq) Ka

- HA(aq) + H2O(l)

-

-

-

Common examples of monoprotic acids in mineral acids include hydrochloric acid (HCl) and nitric acid (HNO3). On the other hand, for organic acids the term mainly indicates the presence of one carboxyl group and sometimes these acids are known as monocarboxylic acid. Examples in organic acids include formic acid (HCOOH), acetic acid (CH3COOH) and benzoic acid (C6H5COOH).

Polyprotic acids

Polyprotic acids, also known as polybasic acids, are able to donate more than one proton per acid molecule, in contrast to monoprotic acids that only donate one proton per molecule. Specific types of polyprotic acids have more specific names, such as diprotic acid (two potential protons to donate) and triprotic acid (three potential protons to donate).

A diprotic acid (here symbolized by H2A) can undergo one or two dissociations depending on the pH. Each dissociation has its own dissociation constant, Ka1 and Ka2.

-

-

-

-

- H2A(aq) + H2O(l)

H3O+(aq) + HA−(aq) Ka1

H3O+(aq) + HA−(aq) Ka1

- H2A(aq) + H2O(l)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- HA−(aq) + H2O(l)

H3O+(aq) + A2−(aq) Ka2

H3O+(aq) + A2−(aq) Ka2

- HA−(aq) + H2O(l)

-

-

-

The first dissociation constant is typically greater than the second; i.e., Ka1 > Ka2. For example, sulfuric acid (H2SO4) can donate one proton to form the bisulfate anion (HSO4−), for which Ka1 is very large; then it can donate a second proton to form the sulfate anion (SO42-), wherein the Ka2 is intermediate strength. The large Ka1 for the first dissociation makes sulfuric a strong acid. In a similar manner, the weak unstable carbonic acid (H2CO3) can lose one proton to form bicarbonate anion (HCO3−) and lose a second to form carbonate anion (CO32-). Both Ka values are small, but Ka1 > Ka2 .

A triprotic acid (H3A) can undergo one, two, or three dissociations and has three dissociation constants, where Ka1 > Ka2 > Ka3.

-

-

-

-

- H3A(aq) + H2O(l)

H3O+(aq) + H2A−(aq) Ka1

H3O+(aq) + H2A−(aq) Ka1

- H3A(aq) + H2O(l)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- H2A−(aq) + H2O(l)

H3O+(aq) + HA2−(aq) Ka2

H3O+(aq) + HA2−(aq) Ka2

- H2A−(aq) + H2O(l)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- HA2−(aq) + H2O(l)

H3O+(aq) + A3−(aq) Ka3

H3O+(aq) + A3−(aq) Ka3

- HA2−(aq) + H2O(l)

-

-

-

An inorganic example of a triprotic acid is orthophosphoric acid (H3PO4), usually just called phosphoric acid. All three protons can be successively lost to yield H2PO4−, then HPO42-, and finally PO43-, the orthophosphate ion, usually just called phosphate. An organic example of a triprotic acid is citric acid, which can successively lose three protons to finally form the citrate ion. Even though the positions of the protons on the original molecule may be equivalent, the successive Ka values will differ since it is energetically less favorable to lose a proton if the conjugate base is more negatively charged.

Although the subsequent loss of each hydrogen ion is less favorable, all of the conjugate bases are present in solution. The fractional concentration, α (alpha), for each species can be calculated. For example, a generic diprotic acid will generate 3 species in solution: H2A, HA-, and A2-. The fractional concentrations can be calculated as below when given either the pH (which can be converted to the [H+]) or the concentrations of the acid with all its conjugate bases:

![\alpha_{H_2 A}={{[H^+]^2} \over {[H^+]^2 + [H^+]K_1 + K_1 K_2}}= {{[H_2 A]} \over {[H_2 A]+[HA^-]+[A^{2-} ]}}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/c4be07c3e960151c5bd3aaed1c6a51db.png)

![\alpha_{HA^- }={{[H^+]K_1} \over {[H^+]^2 + [H^+]K_1 + K_1 K_2}}= {{[HA^-]} \over {[H_2 A]+[HA^-]+[A^{2-} ]}}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/fbdbd30122251efd5ddbec41e624c4aa.png)

![\alpha_{A^{2-}}={{K_1 K_2} \over {[H^+]^2 + [H^+]K_1 + K_1 K_2}}= {{[A^{2-} ]} \over {[H_2 A]+[HA^-]+[A^{2-} ]}}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/f6ac8632c237011599f300e62d916859.png)

A pattern is observed in the above equations and can be expanded to the general n -protic acid that has been deprotonated i -times:

![\alpha_{H_{n-i} A^{i-} }= {{[H^+ ]^{n-i} \displaystyle \prod_{j=0}^{i}K_j} \over { \displaystyle \sum_{i=0}^n \Big[ [H^+ ]^{n-i} \displaystyle \prod_{j=0}^{i}K_j} \Big] }](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/25c0640716e27ce3151ce86c1d2beb21.png) where K0 = 1 and the other K-terms are the dissociation constants for the acid.

where K0 = 1 and the other K-terms are the dissociation constants for the acid.

Neutralization

Neutralization is the reaction between an acid and a base, producing a salt and neutralized base; for example, hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide form sodium chloride and water:

-

- HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) → H2O(l) + NaCl(aq)

Neutralization is the basis of titration, where a pH indicator shows equivalence point when the equivalent number of moles of a base have been added to an acid. It is often wrongly assumed that neutralization should result in a solution with pH 7.0, which is only the case with similar acid and base strengths during a reaction.

Neutralization with a base weaker than the acid results in a weakly acidic salt. An example is the weakly acidic ammonium chloride, which is produced from the strong acid hydrogen chloride and the weak base ammonia. Conversely, neutralizing a weak acid with a strong base gives a weakly basic salt, e.g. sodium fluoride from hydrogen fluoride and sodium hydroxide.

Weak acid/weak base equilibria

In order to lose a proton, it is necessary that the pH of the system rise above the pKa of the protonated acid. The decreased concentration of H+ in that basic solution shifts the equilibrium towards the conjugate base form (the deprotonated form of the acid). In lower-pH (more acidic) solutions, there is a high enough H+ concentration in the solution to cause the acid to remain in its protonated form, or to protonate its conjugate base (the deprotonated form).

Solutions of weak acids and salts of their conjugate bases form buffer solutions.

Applications of acids

There are numerous uses for acids. Acids are often used to remove rust and other corrosion from metals in a process known as pickling. They may be used as an electrolyte in a wet cell battery, such as sulfuric acid in a car battery.

Strong acids, sulfuric acid in particular, are widely used in mineral processing. For example, phosphate minerals react with sulfuric acid to produce phosphoric acid for the production of phosphate fertilizers, and zinc is produced by dissolving zinc oxide into sulfuric acid, purifying the solution and electrowinning.

In the chemical industry, acids react in neutralization reactions to produce salts. For example, nitric acid reacts with ammonia to produce ammonium nitrate, a fertilizer. Additionally, carboxylic acids can be esterified with alcohols, to produce esters.

Acids are used as additives to drinks and foods, as they alter their taste and serve as preservatives. Phosphoric acid, for example, is a component of cola drinks.Acetic acid is used in day to day life as vinegar. Carbonic acid is an important part of some cola drinks and soda. Citric acid is used as a preservative in sauces and pickles.

Tartaric acid is an important component of some commonly used foods like unripened mangoes and tamarind. Natural fruits & vegetables also contain acids. Oxalic acid is present in tomatoes and spinach. Citric acid is present in oranges, lemon and other citrus fruits.

Ascorbic acid is an essential vitamin required in our body and is present in such foods as amla, lemon, citrus fruits, and guava.

Certain acids are used as drugs. Acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) is used as a pain killer and for bringing down fevers.

Acids play very important roles in the human body. The hydrochloric acid present in our stomach aids in digestion by breaking down large and complex food molecules. Amino acids are required for synthesis of proteins required for growth and repair of our body tissues. Fatty acids are also required for growth and repair of body tissues. Nucleic acids are important for the manufacturing of DNA, RNA and transmission of characters to offspring through genes. Carbonic acid is important for maintenance of pH equilibrium in the body.

Acid catalysis

Acids are used as catalysts in industrial and organic chemistry; for example, sulfuric acid is used in very large quantities in the alkylation process to produce gasoline. Strong acids, such as sulfuric, phosphoric and hydrochloric acids also effect dehydration and condensation reactions. In biochemistry, many enzymes employ acid catalysis.[7]

Biological occurrence

Many biologically important molecules are acids. Nucleic acids, which contain acidic phosphate groups, include DNA and RNA. Nucleic acids contain the genetic code that determines many of an organism's characteristics, and is passed from parents to offspring. DNA contains the chemical blueprint for the synthesis of proteins which are made up of amino acid subunits. Cell membranes contain fatty acid esters such as phospholipids.

An α-amino acid has a central carbon (the α or alpha carbon) which is covalently bonded to a carboxyl group (thus they are carboxylic acids), an amino group, a hydrogen atom and a variable group. The variable group, also called the R group or side chain, determines the identity and many of the properties of the a specific amino acid. In glycine, the simplest amino acid, the R group is a hydrogen atom, but in all other amino acids it is contains one or more carbon atoms bonded to hydrogens, and may contain other elements such as sulfur, oxygen or nitrogen. With the exception of glycine, naturally occurring amino acids are chiral and almost invariably occur in the L-configuration. Peptidoglycan, found in some bacterial cell walls contains some D-amino acids. At physiological pH, typically around 7, free amino acids exist in a charged form, where the acidic carboxyl group (-COOH) loses a proton (-COO−) and the basic amine group (-NH2) gains a proton (-NH3+). The entire molecule has a net neutral charge and is a zwitterion, with the exception of amino acids with basic or acidic side chains. Aspartic acid, for example, possesses one protonated amine and two deprotonated carboxyl groups, for a net charge of -1 at physiological pH.

Fatty acids and fatty acid derivatives are another group of carboxylic acids that play a significant role in biology. These contain long hydrocarbon chains and a carboxylic acid group on one end. The cell membrane of nearly all organisms is primarily made up of a phospholipid bilayer, a micelle of hydrophobic fatty acid esters with polar, hydrophilic phosphate "head" groups. Membranes contain additional components, some of which can participate in acid-base reactions.

In humans and many other animals, hydrochloric acid is a part of the gastric acid secreted within the stomach to help hydrolyze proteins and polysaccharides, as well as converting the inactive pro-enzyme, pepsinogen into the enzyme, pepsin. Some organisms produce acids for defense; for example, ants produce formic acid.

Acid-base equilibrium plays a critical role in regulating mammalian breathing. Oxygen gas (O2) drives cellular respiration, the process by which animals release the chemical potential energy stored in food, producing carbon dioxide (CO2) as a byproduct. Oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged in the lungs, and the body responds to changing energy demands by adjusting the rate of ventilation. For example, during periods of exertion the body rapidly breaks down stored carbohydrates and fat, releasing CO2 into the blood stream. In aqueous solutions such as blood CO2 exists in equilibrium with carbonic acid and bicarbonate ion.

- CO2 + H2O

H2CO3

H2CO3  H+ + HCO3−

H+ + HCO3−

It is the decrease in pH that signals the brain to breath faster and deeper, expelling the excess CO2 and resupplying the cells with O2.

Cell membranes are generally impermeable to charged or large, polar molecules because of the lipophilic fatty acyl chains comprising their interior. Many biologically important molecules, including a number of pharmaceutical agents, are organic weak acids which can cross the membrane in their protonated, uncharged form but not in their charged form (i.e. as the conjugate base). For this reason the activity of many drugs can be enhanced or inhibited by the use of antacids or acidic foods. The charged form, however, is often more soluble in blood and cytosol, both aqueous environments. When the extracellular environment is more acidic than the neutral pH within the cell, certain acids will exist in their neutral form and will be membrane soluble, allowing them to cross the phospholipid bilayer. Acids that lose a proton at the intracellular pH will exist in their soluble, charged form and are thus able to diffuse through the cytosol to their target. Ibuprofen, aspirin and penicillin are examples of drugs that are weak acids.

Common acids

Mineral acids

- Hydrogen halides and their solutions: hydrochloric acid (HCl), hydrobromic acid (HBr), hydroiodic acid (HI)

- Halogen oxoacids: hypochloric acid, chloric acid, perchloric acid, periodic acid and corresponding compounds for bromine and iodine

- Sulfuric acid (H2SO4)

- Fluorosulfuric acid

- Nitric acid (HNO3)

- Phosphoric acid (H3PO4)

- Fluoroantimonic acid

- Fluoroboric acid

- Hexafluorophosphoric acid

- Chromic acid (H2CrO4)

- Boric acid (H3BO3)

Sulfonic acids

- Methanesulfonic acid (or mesylic acid, CH3SO3H)

- Ethanesulfonic acid (or esylic acid, CH3CH2SO3H)

- Benzenesulfonic acid (or besylic acid, C6H5SO3H)

- p-Toluenesulfonic acid (or tosylic acid, CH3C6H4SO3H)

- Trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (or triflic acid, CF3SO3H)

Carboxylic acids

- Acetic acid

- Citric acid

- Formic acid

- Gluconic acid

- Lactic acid

- Oxalic acid

- Tartaric acid

Vinylogous carboxylic acids

- Ascorbic acid

- Meldrum's acid

Nucleic acids

- Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)

- Ribonucleic acid (RNA)

See also

- Chemistry

- Acid value

- Acid salt

- Base

- Basic salt

- Binary acid

- Hard and soft acids and bases (HSAB theory)

- Vitriol

- Acid-base extraction

- Environment

- Acid rain

- Ocean acidification

- Acid sulfate soil

References

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary: acid

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ebbing, D.D., & Gammon, S. D. (2005). General chemistry (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0618511776

- ↑ pKa's of Inorganic and Oxo-Acids

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Section 8: Electrolytes, Electromotive forces and Chemical Equilibrium

- ↑ pKa values for HClOn from Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0130399137.

- ↑ pKa Data Compiled by R. Williams

- ↑ Voet, Judith G.; Voet, Donald (2004). Biochemistry. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. pp. 496-500. ISBN 9780471193500.

- Listing of strengths of common acids and bases

- Zumdahl, Chemistry, 4th Edition.

- Ebbing, D.D., & Gammon, S. D. (2005). General chemistry (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0618511776

- Pavia, D.L., Lampman, G.M., & Kriz, G.S. (2004). Organic chemistry volume 1: Organic chemistry 351. Mason, OH: Cenage Learning. ISBN 9780759342724

External links

- Science Aid: Acids and Bases Information for High School students

- Curtipot: Acid-Base equilibria diagrams, pH calculation and titration curves simulation and analysis - freeware

- A summary of the Properties of Acids for the beginning chemistry student

- The UN ECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution

![K_a = \frac{[\mbox{H}^+] [\mbox{A}^-]}{[\mbox{HA}]}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/11cd97f7029fe8c80b6b3ed221b3ce0c.png)