MP3

| Filename extension | .mp3[1] |

|---|---|

| Internet media type | audio/mpeg,[2] audio/MPA,[3] audio/mpa-robust[4] |

| Initial release | 1993[5] |

| Type of format | Audio compression format, audio file format |

| Standard(s) | ISO/IEC 11172-3,[5] ISO/IEC 13818-3[6] |

MPEG-1 or MPEG-2 Audio Layer 3 (or III),[4] more commonly referred to as MP3, is a patented digital audio encoding format using a form of lossy data compression. It is a common audio format for consumer audio storage, as well as a de facto standard of digital audio compression for the transfer and playback of music on digital audio players.

MP3 is an audio-specific format that was designed by the Moving Picture Experts Group as part of its MPEG-1 standard and later extended in MPEG-2 standard. The first MPEG subgroup - Audio group was formed by several teams of engineers at Fraunhofer IIS, University of Hannover, AT&T-Bell Labs, Thomson-Brandt, CCETT, and others.[7] MPEG-1 Audio (MPEG-1 Part 3), which included MPEG-1 Audio Layer I, II and III was approved as a committee draft of ISO/IEC standard in 1991,[8][9] finalised in 1992[10] and published in 1993 (ISO/IEC 11172-3:1993[5]). Backwards compatible MPEG-2 Audio (MPEG-2 Part 3) with additional bit rates and sample rates was published in 1995 (ISO/IEC 13818-3:1995).[6][11]

The use in MP3 of a lossy compression algorithm is designed to greatly reduce the amount of data required to represent the audio recording and still sound like a faithful reproduction of the original uncompressed audio for most listeners. An MP3 file that is created using the setting of 128 kbit/s will result in a file that is about 11 times smaller[note 1] than the CD file created from the original audio source. An MP3 file can also be constructed at higher or lower bit rates, with higher or lower resulting quality.

The compression works by reducing accuracy of certain parts of sound that are deemed beyond the auditory resolution ability of most people. This method is commonly referred to as perceptual coding.[13] It uses psychoacoustic models to discard or reduce precision of components less audible to human hearing, and then records the remaining information in an efficient manner.

This technique is often presented as relatively conceptually similar to the principles used by JPEG, an image compression format. The specific algorithms, however, are rather different: JPEG uses a built-in vision model that is very widely tuned (as is necessary for images), while MP3 uses a complex, precise masking model that is much more signal dependent.

Contents |

History

Development

The MP3 lossy audio data compression algorithm takes advantage of a perceptual limitation of human hearing called auditory masking. In 1894, Alfred Marshall Mayer reported that a tone could be rendered inaudible by another tone of lower frequency.[14] In 1959, Richard Ehmer described a complete set of auditory curves regarding this phenomenon.[15] Ernst Terhardt et al. created an algorithm describing auditory masking with high accuracy.[16] This work added to a variety of reports from authors dating back to Fletcher, and to the work that initially determined critical ratios and critical bandwidths.

The psychoacoustic masking codec was first proposed in 1979, apparently independently, by Manfred R. Schroeder, et al.[17] from AT&T-Bell Labs in Murray Hill, NJ, and M. A. Krasner[18] both in the United States. Krasner was the first to publish and to produce hardware for speech (not usable as music bit compression), but the publication of his results as a relatively obscure Lincoln Laboratory Technical Report did not immediately influence the mainstream of psychoacoustic codec development. Manfred Schroeder was already a well-known and revered figure in the worldwide community of acoustical and electrical engineers, but his paper was not much noticed, since it described negative results due to the particular nature of speech and the linear predictive coding (LPC) gain present in speech. Both Krasner and Schroeder built upon the work performed by Eberhard F. Zwicker in the areas of tuning and masking of critical bands,[19][20] that in turn built on the fundamental research in the area from Bell Labs of Harvey Fletcher and his collaborators.[21] A wide variety of (mostly perceptual) audio compression algorithms were reported in IEEE's refereed Journal on Selected Areas in Communications.[22] That journal reported in February 1988 on a wide range of established, working audio bit compression technologies, some of them using auditory masking as part of their fundamental design, and several showing real-time hardware implementations.

The immediate predecessors of MP3 were "Optimum Coding in the Frequency Domain" (OCF),[23] and Perceptual Transform Coding (PXFM).[24] These two codecs, along with block-switching contributions from Thomson-Brandt, were merged into a codec called ASPEC, which was submitted to MPEG, and which won the quality competition, but that was mistakenly rejected as too complex to implement. The first practical implementation of an audio perceptual coder (OCF) in hardware (Krasner's hardware was too cumbersome and slow for practical use), was an implementation of a psychoacoustic transform coder based on Motorola 56000 DSP chips.

MP3 is directly descended from OCF and PXFM. MP3 represents the outcome of the collaboration of Karlheinz Brandenburg, working as a postdoc at AT&T-Bell Labs with James D. (JJ) Johnston of AT&T-Bell Labs, collaborating with the Fraunhofer Society for Integrated Circuits, Erlangen, with relatively minor contributions from the MP2 branch of psychoacoustic sub-band coders.

MPEG-1 Audio Layer 2 encoding began as the Digital Audio Broadcast (DAB) project managed by Egon Meier-Engelen of the Deutsche Forschungs- und Versuchsanstalt für Luft- und Raumfahrt (later on called Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt, German Aerospace Center) in Germany. The European Community financed this project, commonly known as EU-147 (or Eureka 147), from 1987 to 1994 as a part of the EUREKA research program. MUSICAM Audio Coding was developed as part of the Eureka 147 project and has been subject to the standardization process within the ISO/Moving Pictures Expert Group (MPEG).

As a doctoral student at Germany's University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Karlheinz Brandenburg began working on digital music compression in the early 1980s, focusing on how people perceive music. He completed his doctoral work in 1989 and became an assistant professor at Erlangen-Nuremberg. While there, he continued to work on music compression with scientists at the Fraunhofer Society (in 1993 he joined the staff of the Fraunhofer Institute).[25]

Standardization

In 1991, there were only two proposals available that could be completely assessed for an MPEG audio standard: Musicam (Masking pattern adapted Universal Subband Integrated Coding And Multiplexing) (a.k.a. MUSICAM) and ASPEC (Adaptive Spectral Perceptual Entropy Coding). The Musicam technique, as proposed by Philips (The Netherlands), CCETT (France) and Institut für Rundfunktechnik (Germany) was chosen due to its simplicity and error robustness, as well as its low computational power associated with the encoding of high quality compressed audio.[26] The Musicam format, based on sub-band coding, was the basis of the MPEG Audio compression format (sampling rates, structure of frames, headers, number of samples per frame).

Much of its technology and ideas were incorporated into the definition of ISO MPEG Audio Layer I and Layer II and the filter bank alone into Layer III (MP3) format as part of the computationally inefficient hybrid filter bank. Under the chairmanship of Professor Musmann (University of Hannover) the editing of the standard was made under the responsibilities of Leon van de Kerkhof (Layer I) and Gerhard Stoll (Layer II).

ASPEC was the joint proposal of AT&T Bell Laboratories, Thomson Consumer Electronics, Fraunhofer Society and CNET.[27] It provided the highest coding efficiency.

A working group consisting of Leon van de Kerkhof (The Netherlands), Gerhard Stoll (Germany), Leonardo Chiariglione (Italy), Yves-François Dehery (France), Karlheinz Brandenburg (Germany) and James D. Johnston (USA) took ideas from ASPEC, integrated the filter bank from Layer 2, added some of their own ideas and created MP3, which was designed to achieve the same quality at 128 kbit/s as MP2 at 192 kbit/s.

All algorithms for MPEG-1 Audio Layer I, II and III were approved in 1991[8][9] and finalized in 1992[10] as part of MPEG-1, the first standard suite by MPEG, which resulted in the international standard ISO/IEC 11172-3 (a.k.a. MPEG-1 Audio or MPEG-1 Part 3), published in 1993.[5] Further work on MPEG audio[28] was finalized in 1994 as part of the second suite of MPEG standards, MPEG-2, more formally known as international standard ISO/IEC 13818-3 (a.k.a. MPEG-2 Part 3 or backwards compatible MPEG-2 Audio or MPEG-2 Audio BC[11]), originally published in 1995.[6][29] MPEG-2 Part 3 (ISO/IEC 13818-3) defined additional bit rates and sample rates for MPEG-1 Audio Layer I, II and III. The new sampling rates are exactly half that of those originally defined for MPEG-1 Audio. MPEG-2 Part 3 also enhanced MPEG-1's audio by allowing the coding of audio programs with more than two channels, up to 5.1 multichannel.[28] There is also MPEG-2.5 audio, a proprietary unofficial extension developed by Fraunhofer IIS. It enables MP3 to work satisfactorily at very low bitrates and added lower sampling frequencies.[30][31] MPEG-2.5 was not developed by MPEG and was never approved as an international standard.

| Version | International Standard[*] | First public release date (First edition) | Latest public release date (edition) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPEG-1 Audio Layer III | ISO/IEC 11172-3 (MPEG-1 Part 3) | 1993 | |

| MPEG-2 Audio Layer III | ISO/IEC 13818-3 (MPEG-2 Part 3) | 1995 | 1998 |

| MPEG-2.5 Audio Layer III | nonstandard, proprietary |

- Note: The ISO standard ISO/IEC 11172-3 (a.k.a. MPEG-1 Audio) defined three formats: the MPEG-1 Audio Layer I, Layer II and Layer III. The ISO standard ISO/IEC 13818-3 (a.k.a. MPEG-2 Audio) defined extended version of the MPEG-1 Audio - MPEG-2 Audio Layer I, Layer II and Layer III. MPEG-2 Audio (MPEG-2 Part 3) should not be confused with MPEG-2 AAC (MPEG-2 Part 7 - ISO/IEC 13818-7).[11]

Compression efficiency of encoders is typically defined by the bit rate, because compression ratio depends on the bit depth and sampling rate of the input signal. Nevertheless, compression ratios are often published. They may use the Compact Disc (CD) parameters as references (44.1 kHz, 2 channels at 16 bits per channel or 2×16 bit), or sometimes the Digital Audio Tape (DAT) SP parameters (48 kHz, 2×16 bit). Compression ratios with this latter reference are higher, which demonstrates the problem with use of the term compression ratio for lossy encoders.

Karlheinz Brandenburg used a CD recording of Suzanne Vega's song "Tom's Diner" to assess and refine the MP3 compression algorithm. This song was chosen because of its nearly monophonic nature and wide spectral content, making it easier to hear imperfections in the compression format during playbacks. Some jokingly refer to Suzanne Vega as "The mother of MP3".[33] Some more critical audio excerpts (glockenspiel, triangle, accordion, etc.) were taken from the EBU V3/SQAM reference compact disc and have been used by professional sound engineers to assess the subjective quality of the MPEG Audio formats. This particular track has an interesting property in that the two channels are almost, but not completely, the same, leading to a case where Binaural Masking Level Depression causes spatial unmasking of noise artifacts unless the encoder properly recognizes the situation and applies corrections similar to those detailed in the MPEG-2 AAC psychoacoustic model.

Going public

A reference simulation software implementation, written in the C language and later known as ISO 11172-5, was developed (in 1991-1996) by the members of the ISO MPEG Audio committee in order to produce bit compliant MPEG Audio files (Layer 1, Layer 2, Layer 3). It was approved as a committee draft of ISO/IEC technical report in March 1994 and printed as document CD 11172-5 in April 1994.[34] It was approved as a draft technical report (DTR/DIS) in November 1994,[35] finalised in 1996 and published as international standard ISO/IEC TR 11172-5:1998 in 1998.[36] The reference software in C language was later published as a freely available ISO standard.[37] Working in non-real time on a number of operating systems, it was able to demonstrate the first real time hardware decoding (DSP based) of compressed audio. Some other real time implementation of MPEG Audio encoders were available for the purpose of digital broadcasting (radio DAB, television DVB) towards consumer receivers and set top boxes.

On July 7, 1994, the Fraunhofer Society released the first software MP3 encoder called l3enc.[38] The filename extension .mp3 was chosen by the Fraunhofer team on July 14, 1995 (previously, the files had been named .bit).[1] With the first real-time software MP3 player Winplay3 (released September 9, 1995) many people were able to encode and play back MP3 files on their PCs. Because of the relatively small hard drives back in that time (~ 500-1000 MB) lossy compression was essential to store non-instrument based (see tracker and MIDI) music for playback on computer.

Internet

From the second half of 1994 through the late 1990s, MP3 files began to spread on the Internet. The popularity of MP3s began to rise rapidly with the advent of Nullsoft's audio player Winamp, released in 1997. In 1998, the first portable solid state digital audio player MPMan, developed by SaeHan Information Systems which is headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, was released and the Rio PMP300 was sold afterwards, despite legal suppression efforts by the RIAA.[39]

In November 1997, the website mp3.com was offering thousands of MP3s created by independent artists for free.[39] The small size of MP3 files enabled widespread peer-to-peer file sharing of music ripped from CDs, which would have previously been nearly impossible. The first large peer-to-peer filesharing network, Napster, was launched in 1999.

In 1996, the song ‘Until it sleeps’ by Metallica became the first track to be illegally copied from CD, encoded as an MP3, and made available on the Internet by a user operating under the nickname ‘NetFrack’.[40] The ease of creating and sharing MP3s resulted in widespread copyright infringement. Major record companies argue that this free sharing of music reduces sales, and call it "music piracy". They reacted by pursuing lawsuits against Napster (which was eventually shut down and later sold) and against individual users who engaged in file sharing.

Despite the popularity of the MP3 format, online music retailers often use other proprietary formats that are encrypted or obfuscated in order to make it difficult to use purchased music files in ways not specifically authorized by the record companies. Attempting to control the use of files in this way is known as Digital Rights Management. Record companies argue that this is necessary to prevent the files from being made available on peer-to-peer file sharing networks. This has other side effects, though, such as preventing users from playing back their purchased music on different types of devices. However, the audio content of these files can usually be converted into an unencrypted format. For instance, users are often allowed to burn files to audio CD, which requires conversion to an unencrypted audio format.

Unauthorized MP3 file sharing continues on next-generation peer-to-peer networks. Some authorized services, such as Beatport, Bleep, Juno Records, eMusic, Zune Marketplace, Walmart.com, and Amazon.com sell unrestricted music in the MP3 format.

Encoding audio

The MPEG-1 standard does not include a precise specification for an MP3 encoder, but does provide example psychoacoustic models, rate loop, and the like in the non-normative part of the original standard.[41] At present, these suggested implementations are quite dated. Implementers of the standard were supposed to devise their own algorithms suitable for removing parts of the information from the audio input. As a result, there are many different MP3 encoders available, each producing files of differing quality. Comparisons are widely available, so it is easy for a prospective user of an encoder to research the best choice. It must be kept in mind that an encoder that is proficient at encoding at higher bit rates (such as LAME) is not necessarily as good at lower bit rates.

During encoding, 576 time-domain samples are taken and are transformed to 576 frequency-domain samples. If there is a transient, 192 samples are taken instead of 576. This is done to limit the temporal spread of quantization noise accompanying the transient. (See psychoacoustics.)

Decoding audio

Decoding, on the other hand, is carefully defined in the standard. Most decoders are "bitstream compliant", which means that the decompressed output – that they produce from a given MP3 file – will be the same, within a specified degree of rounding tolerance, as the output specified mathematically in the ISO/IEC standard document (ISO/IEC 11172-3). Therefore, comparison of decoders is usually based on how computationally efficient they are (i.e., how much memory or CPU time they use in the decoding process).

Audio quality

When performing lossy audio encoding, such as creating an MP3 file, there is a trade-off between the amount of space used and the sound quality of the result. Typically, the creator is allowed to set a bit rate, which specifies how many kilobits the file may use per second of audio. The higher the bit rate, the larger the compressed file will be, and, generally, the closer it will sound to the original file.

With too low a bit rate, compression artifacts (i.e. sounds that were not present in the original recording) may be audible in the reproduction. Some audio is hard to compress because of its randomness and sharp attacks. When this type of audio is compressed, artifacts such as ringing or pre-echo are usually heard. A sample of applause compressed with a relatively low bit rate provides a good example of compression artifacts.

Besides the bit rate of an encoded piece of audio, the quality of MP3 files also depends on the quality of the encoder itself, and the difficulty of the signal being encoded. As the MP3 standard allows quite a bit of freedom with encoding algorithms, different encoders may feature quite different quality, even with identical bit rates. As an example, in a public listening test featuring two different MP3 encoders at about 128 kbit/s,[42] one scored 3.66 on a 1–5 scale, while the other scored only 2.22.

Quality is dependent on the choice of encoder and encoding parameters.[43] However, in 1998, MP3 at 128 kbit/s was providing lower quality than AAC at 96 kbit/s.[44]

The simplest type of MP3 file uses one bit rate for the entire file — this is known as Constant Bit Rate (CBR) encoding. Using a constant bit rate makes encoding simpler and faster. However, it is also possible to create files where the bit rate changes throughout the file. These are known as Variable Bit Rate (VBR) files. The idea behind this is that, in any piece of audio, some parts will be much easier to compress, such as silence or music containing only a few instruments, while others will be more difficult to compress. So, the overall quality of the file may be increased by using a lower bit rate for the less complex passages and a higher one for the more complex parts. With some encoders, it is possible to specify a given quality, and the encoder will vary the bit rate accordingly. Users who know a particular "quality setting" that is transparent to their ears can use this value when encoding all of their music, and not need to worry about performing personal listening tests on each piece of music to determine the correct bit rate.

Perceived quality can be influenced by listening environment (ambient noise), listener attention, and listener training and in most cases by listener audio equipment (such as sound cards, speakers and headphones).

A test given to new students by Stanford University Music Professor Jonathan Berger showed that student preference for MP3 quality music has risen each year. Berger said the students seem to prefer the 'sizzle' sounds that MP3s bring to music.[45] Others have reached the same conclusion, and some record producers have begun to mix music specifically to be heard on iPods and mobile phones.[46]

Bit rate

Several bit rates are specified in the MPEG-1 Audio Layer III standard: 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 80, 96, 112, 128, 160, 192, 224, 256 and 320 kbit/s, and the available sampling frequencies are 32, 44.1 and 48 kHz.[31] Additional extensions were defined in MPEG-2 Audio Layer III: bit rates 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 80, 96, 112, 128, 144, 160 kbit/s and sampling frequencies 16, 22.05 and 24 kHz.[31] Although MP3 can be used with data rates in the range between 8 kbit/s and 320 kbit/s, it is not recommended to use data rates below 80 kbit/s for mono and 160 kbit/s for stereo audio. For very low data rates, MPEG-4 Audio compression formats are more suitable than MP3.[30]

A sample rate of 44.1 kHz is almost always used, because this is also used for CD audio, the main source used for creating MP3 files. A greater variety of bit rates are used on the Internet. The rate of 128 kbit/s is the most common, offering adequate audio quality in a relatively small space. As Internet bandwidth availability and hard drive sizes have increased, higher bit rates like 160 and 192 kbit/s have increased in popularity.

Uncompressed audio as stored on an audio-CD has a bit rate of 1,411.2 kbit/s,[note 2] so the bitrates 128, 160 and 192 kbit/s represent compression ratios of approximately 11:1, 9:1 and 7:1 respectively.

Non-standard bit rates up to 640 kbit/s can be achieved with the LAME encoder and the freeformat option, although few MP3 players can play those files. According to the ISO standard, decoders are only required to be able to decode streams up to 320 kbit/s.[47]

| MPEG-1 Audio Layer III |

MPEG-2 Audio Layer III |

nonstandard proprietary MPEG-2.5 Audio Layer III |

|---|---|---|

| - | 8 | 8 |

| - | 16 | 16 |

| - | 24 | 24 |

| 32 | 32 | 32 |

| 40 | 40 | 40 |

| 48 | 48 | 48 |

| 56 | 56 | 56 |

| 64 | 64 | 64 |

| 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 96 | 96 | 96 |

| 112 | 112 | 112 |

| 128 | 128 | 128 |

| - | 144 | 144 |

| 160 | 160 | 160 |

| 192 | - | - |

| 224 | - | - |

| 256 | - | - |

| 320 | - | - |

| MPEG-1 Audio Layer III |

MPEG-2 Audio Layer III |

nonstandard proprietary MPEG-2.5 Audio Layer III |

|---|---|---|

| - | - | 8000 Hz |

| - | - | 11025 Hz |

| - | - | 12000 Hz |

| - | 16000 Hz | - |

| - | 22050 Hz | - |

| - | 24000 Hz | - |

| 32000 Hz | - | - |

| 44100 Hz | - | - |

| 48000 Hz | - | - |

VBR

MPEG audio may use variable bitrate (VBR), accomplished via bitrate switching on a per-frame basis, but only layer III decoders must support it.[31][49][50][51] VBR is used when the goal is to achieve a fixed level of quality. The final file size of a VBR encoding is less predictable than with constant bitrate. Average bitrate is VBR implemented as a compromise between the two – the bitrate is allowed to vary for more consistent quality, but is controlled to remain near an average value chosen by the user, for predictable file sizes. Although technically an MP3 decoder must support VBR to be standards compliant, historically some decoders have bugs with VBR decoding, particularly before VBR encoders became widespread.

Layer III audio can also use a "bit reservoir", a partially full frame's ability to hold part of the next frame's audio data, allowing temporary changes in effective bitrate, even in a constant bitrate stream.[31][49]

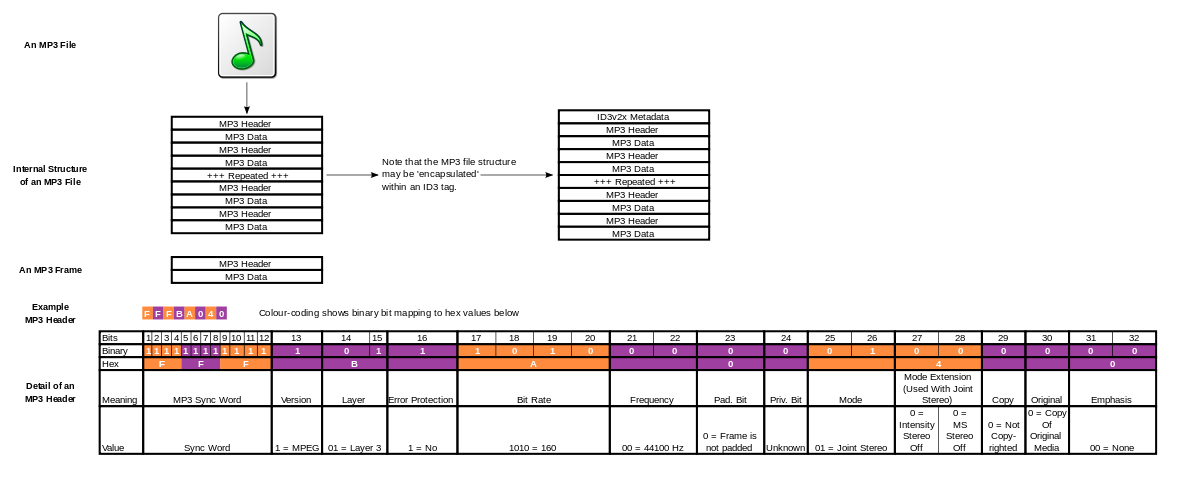

File structure

An MP3 file is made up of multiple MP3 frames, which consist of a header and a data block. This sequence of frames is called an elementary stream. Frames are not independent items ("byte reservoir") and therefore cannot be extracted on arbitrary frame boundaries. The MP3 Data blocks contain the (compressed) audio information in terms of frequencies and amplitudes. The diagram shows that the MP3 Header consists of a sync word, which is used to identify the beginning of a valid frame. This is followed by a bit indicating that this is the MPEG standard and two bits that indicate that layer 3 is used; hence MPEG-1 Audio Layer 3 or MP3. After this, the values will differ, depending on the MP3 file. ISO/IEC 11172-3 defines the range of values for each section of the header along with the specification of the header. Most MP3 files today contain ID3 metadata, which precedes or follows the MP3 frames; as noted in the diagram.

Design limitations

There are several limitations inherent to the MP3 format that cannot be overcome by any MP3 encoder. Newer audio compression formats such as Vorbis, WMA Pro and AAC are generally void of these limitations.[52]

In technical terms, MP3 is limited in the following ways:

- Time resolution can be too low for highly transient signals and may cause smearing of percussive sounds.

- Due to the tree structure of the filter bank, pre-echo problems are made worse, as the combined impulse response of the two filter banks does not, and cannot, provide an optimum solution in time/frequency resolution.

- The combining of the two filter banks' outputs creates aliasing problems that must be handled partially by the "aliasing compensation" stage; however, that creates excess energy to be coded in the frequency domain, thereby decreasing coding efficiency.

- Frequency resolution is limited by the small long block window size, which decreases coding efficiency.

- There is no scale factor band for frequencies above 15.5/15.8 kHz.

- Joint stereo is done only on a frame-to-frame basis.

- Internal handling of the bit reservoir increases encoding delay.

- Encoder/decoder overall delay is not defined, which means there is no official provision for gapless playback. However, some encoders such as LAME can attach additional metadata that will allow players that can handle it to deliver seamless playback.

- The data stream can contain an optional checksum, but the checksum only protects the header data, not the audio data.

ID3 and other tags

- Main articles: ID3 and APEv2 tag

A "tag" in an audio file is a section of the file that contains metadata such as the title, artist, album, track number or other information about the file's contents. The MP3 standards don't define tag formats for MP3 files, nor is there a standard container format that would support metadata and obviate the need for tags.

However, several de facto standards for tag formats exist. As of 2010, the most widespread are ID3v1 and ID3v2, and the more recently introduced APEv2. These tags are normally embedded at the beginning or end of MP3 files, separate from the actual MP3 frame data. MP3 decoders normally either read info from the tags, or just treat them as ignorable, non-MP3 junk data.

Playing & editing software often contains tag editing functionality, but there are also tag editor applications dedicated to the purpose.

Aside from metadata pertaining to the audio content, tags may also be used for DRM.

Volume normalization

Since volume levels of different audio sources can vary greatly, it is sometimes desirable to adjust the playback volume of audio files such that a consistent average volume is perceived. The idea is to control the average volume across multiple files, not the volume peaks in a single file. This gain normalization, while similar in purpose, is distinct from dynamic range compression (DRC), which is a form of normalization used in audio mastering. Gain normalization may defeat the intent of recording artists and audio engineers who deliberately set the volume levels of the audio they recorded.

A few standards for storing the average volume of an MP3 file in its metadata tags, enabling a specially designed player to automatically adjust the overall playback volume for each file, have been proposed. A popular and widely implemented such proposal is "Replay Gain", which is not MP3-specific. When used in MP3s, it is stored differently by different encoders, and as of 2008, Replay Gain-aware players don't yet support all formats.

Licensing and patent issues

Many organizations have claimed ownership of patents related to MP3 decoding or encoding. These claims have led to a number of legal threats and actions from a variety of sources, resulting in uncertainty about which patents must be licensed in order to create MP3 products without committing patent infringement in countries that allow software patents.

The various MP3-related patents expire on dates ranging from 2007 to 2017 in the U.S.[53] The initial near-complete MPEG-1 standard (parts 1, 2 and 3) was publicly available in December 6, 1991 as ISO CD 11172.[54][55] In the United States, patents cannot claim inventions that were already publicly disclosed more than a year prior to the filing date, but for patents filed prior to June 8, 1995, submarine patents made it possible to extend the effective lifetime of a patent through application extensions. Patents filed for anything disclosed in ISO CD 11172 a year or more after its publication are questionable; if only the known MP3 patents filed by December 1992 are considered, then MP3 decoding may be patent free in the US by December 2012.[56]

Thomson Consumer Electronics claims to control MP3 licensing of the Layer 3 patents in many countries, including the United States, Japan, Canada and EU countries.[57] Thomson has been actively enforcing these patents.

MP3 license revenues generated about €100 million for the Fraunhofer Society in 2005.[58]

In September 1998, the Fraunhofer Institute sent a letter to several developers of MP3 software stating that a license was required to "distribute and/or sell decoders and/or encoders". The letter claimed that unlicensed products "infringe the patent rights of Fraunhofer and Thomson. To make, sell and/or distribute products using the [MPEG Layer-3] standard and thus our patents, you need to obtain a license under these patents from us."[59]

However, there exist both free and/or proprietary alternatives, with free formats such as Vorbis, AAC, and others. Microsoft's usage of its own proprietary Windows Media format allows it to avoid licensing issues associated with these patents by avoiding usage of the MP3 format entirely. Until the key patents expire, unlicensed encoders and players could be infringing in countries where the patents are valid.

In spite of the patent restrictions, the perpetuation of the MP3 format continues. The reasons for this appear to be the network effects caused by:

- familiarity with the format

- the large quantity of music now available in the MP3 format

- the wide variety of existing software and hardware that takes advantage of the file format and doesn't support the alternatives

- the lack of DRM restrictions, which makes MP3 files easy to edit, copy and play in different portable digital players (Samsung, Apple, Creative, etc.)

- the majority of home users not knowing or not caring about the patents' existence and often not considering such legal issues when choosing their music format for personal use

Additionally, patent holders declined to enforce license fees on free and open source decoders, which allows many free MP3 decoders to develop.[60] Thus, while patent fees have been an issue for companies that attempt to use MP3, they have not meaningfully impacted personal use.

Sisvel S.p.A. and its U.S. subsidiary Audio MPEG, Inc. previously sued Thomson for patent infringement on MP3 technology,[61] but those disputes were resolved in November 2005 with Sisvel granting Thomson a license to their patents. Motorola also recently signed with Audio MPEG to license MP3-related patents.

In September 2006, German officials seized MP3 players from SanDisk's booth at the IFA show in Berlin after an Italian patents firm won an injunction on behalf of Sisvel against SanDisk in a dispute over licensing rights. The injunction was later reversed by a Berlin judge,[62] but that reversal was in turn blocked the same day by another judge from the same court, "bringing the Patent Wild West to Germany" in the words of one commentator.[63]

In February 2007, Texas MP3 Technologies sued Apple, Samsung Electronics and Sandisk in eastern Texas federal court, claiming infringement of a portable MP3 player patent that Texas MP3 said it had been assigned. Apple and Sandisk both settled the claims against them in January 2009.[64] Samsung settled as well.[65]

Alcatel-Lucent has asserted several MP3 coding and compression patents, allegedly inherited from AT&T-Bell Labs, in litigation of its own. In November 2006 (prior to the companies' merger), Alcatel sued Microsoft for allegedly infringing seven patents. On February 23, 2007, a San Diego jury awarded Alcatel-Lucent US $1.52 billion in damages for infringement of two of them.[66] The court subsequently tossed the award, however, finding that one patent had not been infringed and that the other was not even owned by Alcatel-Lucent; it was co-owned by AT&T and Fraunhofer, who had licensed it to Microsoft, the judge ruled.[67] That defense judgment was upheld on appeal in 2008.[68]

Alternative technologies

Many other lossy and lossless audio codecs exist. Among these, mp3PRO, AAC, and MP2 are all members of the same technological family as MP3 and depend on roughly similar psychoacoustic models. The Fraunhofer Gesellschaft owns many of the basic patents underlying these codecs as well, with others held by Dolby Labs, Sony, Thomson Consumer Electronics, and AT&T. In addition, there is also the open source file format Vorbis that has been available free of charge and without any known patent restrictions.

See also

|

|

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Happy Birthday MP3!". Fraunhofer IIS. 2005-07-12. http://www.iis.fraunhofer.de/EN/pr/Presse/pressemitteilungen_2005/20050712_PM_MP3.jsp. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ "The audio/mpeg Media Type - RFC 3003". IETF. November 2000. http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3003. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ↑ "MIME Type Registration of RTP Payload Formats - RFC 3555". IETF. July 2003. http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3555#page-24. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "A More Loss-Tolerant RTP Payload Format for MP3 Audio - RFC 5219". IETF. February 2008. http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5219. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "ISO/IEC 11172-3:1993 - Information technology -- Coding of moving pictures and associated audio for digital storage media at up to about 1,5 Mbit/s -- Part 3: Audio". ISO. 1993. http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=22412. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "ISO/IEC 13818-3:1995 - Information technology -- Generic coding of moving pictures and associated audio information -- Part 3: Audio". ISO. 1995. http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_ics/catalogue_detail_ics.htm?csnumber=22991. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ Chiariglione, Leonardo (2009-09-06). "Riding the Media Bits - MPEG's first Steps". http://ride.chiariglione.org/MPEG's_1st_steps.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 ISO (November 1991). "MPEG Press Release, Kurihama, November 1991". ISO. http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/meetings/kurihama91/kurihama_press.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 ISO (November 1991). "CD 11172-3 - CODING OF MOVING PICTURES AND ASSOCIATED AUDIO FOR DIGITAL STORAGE MEDIA AT UP TO ABOUT 1.5 MBIT/s Part 3 AUDIO" (DOC). neuron2.net. http://neuron2.net/library/mpeg1/MPGAUDIO.DOC. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 ISO (1992-11-06). "MPEG Press Release, London, 6 November 1992". chiariglione.org. http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/meetings/london/london_press.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 ISO (1998-10). "MPEG Audio FAQ Version 9 - MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 BC". ISO. http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/faq/mp1-aud/mp1-aud.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ "CD Audio Facts". Mediatechnics. http://www.mediatechnics.com/cdaudio.htm.

- ↑ Jayant, Nikil; Johnston, James; Safranek, Robert (October 1993). "Signal Compression Based on Models of Human Perception". Proceedings of the IEEE 81 (10): 1385–1422. doi:10.1109/5.241504.

- ↑ Mayer, Alfred Marshall (1894). "Researches in Acoustics". London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine 37: 259–288.

- ↑ Ehmer, Richard H. (1959). "Masking by Tones Vs Noise Bands". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 31: 1253. doi:10.1121/1.1907853.

- ↑ Terhardt, E.; Stoll, G.; Seewann, M. (March 1982). "Algorithm for Extraction of Pitch and Pitch Salience from Complex Tonal Signals". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 71: 679. doi:10.1121/1.387544.

- ↑ Schroeder, M.R.; Atal, B.S.; Hall, J.L. (December 1979). "Optimizing Digital Speech Coders by Exploiting Masking Properties of the Human Ear". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 66: 1647. doi:10.1121/1.383662.

- ↑ Krasner, M. A. (18 June 1979). Digital Encoding of Speech and Audio Signals Based on the Perceptual Requirements of the Auditory System. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/16011.

- ↑ Zwicker, E. F. (1974). "On the Psycho-acoustical Equivalent of Tuning Curves". Proceedings of the Symposium on Psychophysical Models and Physiological Facts in Hearing; held at Tuzing, Oberbayern, April 22–26, 1974.

- ↑ Zwicker, Eberhard; Feldtkeller, Richard (1999) [1967]. Das Ohr als Nachrichtenempfänger [The Ear as a Communication Receiver]. Trans. by Hannes Müsch, Søren Buus, and Mary Florentine. http://asa.aip.org/books/ear.html.

- ↑ Fletcher, Harvey (1995). Speech and Hearing in Communication. Acoustical Society of America. ISBN 1563963930.

- ↑ "Voice Coding for Communications". IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 6 (2). February 1988.

- ↑ Brandenburg, Karlheinz; Seitzer, Dieter (3–6 November 1988). "OCF: Coding High Quality Audio with Data Rates of 64 kbit/s". 85th Convention of Audio Engineering Society. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=4721.

- ↑ Johnston, James D. (February 1988). "Transform Coding of Audio Signals Using Perceptual Noise Criteria". IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 6 (2): 314–323. doi:10.1109/49.608.

- ↑ Ewing, Jack (5 March 2007). "How MP3 Was Born". BusinessWeek. http://www.businessweek.com/globalbiz/content/mar2007/gb20070305_707122.htm. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ International Organization for Standardization (September 1990). "Status report of ISO MPEG". Press release. http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/meetings/santa_clara90/santa_clara_press.htm.

- ↑ "AES E-Library - Aspec-Adaptive Spectral Entropy Coding of High Quality Music Signals". 1991. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=5682. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 International Organization for Standardization (1993-04-02). "Press Release - Adopted at 22nd WG11 meeting". Press release. http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/meetings/sydney93/sydney_press.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ↑ Brandenburg, Karlheinz; Bosi, Marina (February 1997). "Overview of MPEG Audio: Current and Future Standards for Low-Bit-Rate Audio Coding". Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 45 (1/2): 4–21. http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=7871. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 "MP3 technical details (MPEG-2 and MPEG-2.5)". Fraunhofer IIS. September 2007. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080124200925/http://www.iis.fraunhofer.de/EN/bf/amm/projects/mp3/index.jsp.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 Supurovic, Predrag (22 December 1999). "MPEG Audio Frame Header". http://www.mpgedit.org/mpgedit/mpeg_format/mpeghdr.htm. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 (ZIP) ISO/IEC 13818-3:1994(E) - Information Technology - Generic Coding of Moving Pictures and Associated Audio: Audio, 1994-11-11, http://www.mp3-tech.org/programmer/docs/iso13818-3.zip, retrieved 2010-08-04

- ↑ "Fun Facts: Music". The Official Community of Suzanne Vega. http://www.suzannevega.com/music-facts/.

- ↑ MPEG (1994-03-25). "Press Release - Approved at 26th meeting (Paris)". http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/meetings/paris94/paris_press.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ↑ MPEG (1994-11-11). "Press Release - Approved at 29th meeting". http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/meetings/singapore94/singapore_press.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ↑ ISO. "ISO/IEC TR 11172-5:1998 - Information technology -- Coding of moving pictures and associated audio for digital storage media at up to about 1,5 Mbit/s -- Part 5: Software simulation". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=25029. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ↑ (ZIP) ISO/IEC TR 11172-5:1998 - Information technology -- Coding of moving pictures and associated audio for digital storage media at up to about 1,5 Mbit/s -- Part 5: Software simulation (Reference Software), http://standards.iso.org/ittf/PubliclyAvailableStandards/c025029_ISO_IEC_TR_11172-5_1998(E)_Software_Simulation.zip, retrieved 2010-08-05

- ↑ "MP3 Todays Technology". Lots of Informative Information about Music. 2005. http://www.513rocks.com/MP3_Todays_Technology_158.shtml.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Schubert, Ruth (10 February 1999). "Tech-savvy Getting Music For A Song; Industry Frustrated That Internet Makes Free Music Simple". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/archives/1999/9902100013.asp. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ↑ "The MP3, its origins, and its impact". Assorted Material Blog. 27 April 2009. http://johnnyryan.wordpress.com/2009/04/27/the-mp3-its-origins-and-its-impact/. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ "ISO/IEC 11172-3:1993/Cor 1:1996". International Organization for Standardization. 2006. http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=25371. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ Amorim, Roberto (3 August 2003). "Results of 128 kbit/s Extension Public Listening Test". http://www.rjamorim.com/test/128extension/results.html. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ Mares, Sebastian (December 2005). "Results of the public multiformat listening test @ 128 kbps". http://www.listening-tests.info/mf-128-1/results.htm. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ Meares, David; Watanabe, Kaoru; Scheirer, Eric (February 1998) (PDF). Report on the MPEG-2 AAC Stereo Verification Tests. International Organisation for Standardisation. http://david.weekly.org/audio/iso-aac.pdf. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ Dougherty, Dale (1 March 2009). "The Sizzling Sound of Music". O'Reilly Radar. http://radar.oreilly.com/2009/03/the-sizzling-sound-of-music.html.

- ↑ Spence, Nick (5 March 2009). "iPod generation prefer MP3 fidelity to CD". Computer Dealer News. http://www.itbusiness.ca/it/client/en/cdn/News.asp?id=52299.

- ↑ Bouvigne, Gabriel (28 November 2006). "freeformat at 640 kbit/s and foobar2000, possibilities?". http://www.hydrogenaudio.org/forums/index.php?s=&showtopic=38808&view=findpost&p=452751. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ↑ "Guide to command line options (in CVS)". http://lame.cvs.sourceforge.net/viewvc/lame/lame/USAGE. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "GPSYCHO – Variable Bit Rate". LAME MP3 Encoder. http://lame.sourceforge.net/vbr.php. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "TwoLAME: MPEG Audio Layer II VBR". http://www.twolame.org/doc/vbr.html. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ ISO MPEG Audio Subgroup. "MPEG Audio FAQ Version 9: MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 BC". http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/faq/mp1-aud/mp1-aud.htm#15. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ Brandenburg, Karlheinz (1999). "MP3 and AAC Explained" (PDF). http://www.telos-systems.com/techtalk/hosted/Brandenburg_mp3_aac.pdf.

- ↑ "A Big List of MP3 Patents (and supposed expiration dates)". tunequest. 26 February 2007. http://www.tunequest.org/a-big-list-of-mp3-patents/20070226/.

- ↑ Berkeley.edu

- ↑ Berkeley.edu

- ↑ Cogliati, Josh (20 July 2008). "Patent Status of MPEG-1, H.261 and MPEG-2". Kuro5hin. http://www.kuro5hin.org/story/2008/7/18/232618/312.

- ↑ "Acoustic Data Compression – MP3 Base Patent". Foundation for a Free Information Infrastructure. 15 January 2005. http://eupat.ffii.org/patents/samples/ep287578/index.en.html. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ Kistenfeger, Muzinée (July 2007). "The Fraunhofer Society (Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft, FhG)". British Consulate-General Munich. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071213035617/http://www.britischebotschaft.de/en/embassy/r&t/notes/rt-fs005_Fraunhofer.html. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ "Early MP3 Patent Enforcement". Chilling Effects Clearinghouse. 1 September 1998. http://www.chillingeffects.org/patent/notice.cgi?NoticeID=464. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ Moody, Glyn (15 June 2007). "Should We Fight for Ogg Vorbis?". Linux Journal. Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070617132646/http://www.linuxjournal.com/node/1000238. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ↑ "Audio MPEG and Sisvel: Thomson sued for patent infringement in Europe and the United States - MP3 players stopped by customs". ZDNet India. 6 October 2005. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071011105618/http://zdnetindia.com/news/pressreleases/stories/128960.html. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ Ogg, Erica (7 September 2006). "SanDisk MP3 seizure order overturned". CNET News. http://news.com.com/2100-1047_3-6113326.html. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ "Sisvel brings Patent Wild West into Germany". IPEG blog. 7 September 2006. http://ipgeek.blogspot.com/2006/09/sisvels-brings-patent-wild-west-into.html. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ↑ "Apple, SanDisk Settle Texas MP3 Patent Spat". IP Law360. 26 January 2009. http://www.law360.com/registrations/user_registration?article_id=84475. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Baker Botts LLP Professionals: Lisa Catherine Kelly - Representative Engagements". Baker Botts LLP. http://www.bakerbotts.com/lawyers/detail.aspx?id=2aa26940-06f4-44a3-865e-12b66912eed5. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Microsoft faces $1.5bn MP3 payout". BBC News. 22 February 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6388273.stm. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ "Microsoft wins reversal of MP3 patent decision". CNET. 6 August 2007. http://news.cnet.com/8301-10784_3-9755745-7.html. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit Decision" (PDF). 25 September 2008. http://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/opinions/07-1546.pdf.

External links

- MP3-history.com, The Story of MP3 — How MP3 was invented, by Fraunhofer IIS

- MPEG.chiariglione.org, MPEG Official Web site

- Wiki.HydrogenAudio.org, MP3

- RFC 3119, A More Loss-Tolerant RTP Payload Format for MP3 Audio

- RFC 3003, The audio/mpeg Media Type

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||