e (mathematical constant)

The mathematical constant e is the unique real number such that the function ex has the same value as the slope of the tangent line, for all values of x.[1] More generally, the only functions equal to their own derivatives are of the form Cex, where C is a constant.[2] The function ex so defined is called the exponential function, and its inverse is the natural logarithm, or logarithm to base e. The number e is also commonly defined as the base of the natural logarithm (using an integral to define the latter), as the limit of a certain sequence, or as the sum of a certain series (see representations of e, below).

The number e is one of the most important numbers in mathematics,[3] alongside the additive and multiplicative identities 0 and 1, the constant π, and the imaginary unit i.

The number e is sometimes called Euler's number after the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler. (e is not to be confused with γ – the Euler–Mascheroni constant, sometimes called simply Euler's constant.)

Since e is transcendental, and therefore irrational, its value cannot be given exactly as a finite or eventually repeating decimal. The numerical value of e truncated to 20 decimal places is

- 2.71828 18284 59045 23536….

|

Contents |

History

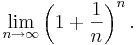

The first references to the constant were published in 1618 in the table of an appendix of a work on logarithms by John Napier.[4] However, this did not contain the constant itself, but simply a list of natural logarithms calculated from the constant. It is assumed that the table was written by William Oughtred. The "discovery" of the constant itself is credited to Jacob Bernoulli, who attempted to find the value of the following expression (which is in fact e):

The first known use of the constant, represented by the letter b, was in correspondence from Gottfried Leibniz to Christiaan Huygens in 1690 and 1691. Leonhard Euler started to use the letter e for the constant in 1727, and the first use of e in a publication was Euler's Mechanica (1736). While in the subsequent years some researchers used the letter c, e was more common and eventually became the standard.

The exact reasons for the use of the letter e are unknown, but it may be because it is the first letter of the word exponential. Another possibility is that Euler used it because it was the first vowel after a, which he was already using for another number, but his reason for using vowels is unknown.

Applications

The compound-interest problem

Jacob Bernoulli discovered this constant by studying a question about compound interest.

One simple example is an account that starts with $1.00 and pays 100% interest per year. If the interest is credited once, at the end of the year, the value is $2.00; but if the interest is computed and added twice in the year, the $1 is multiplied by 1.5 twice, yielding $1.00×1.5² = $2.25. Compounding quarterly yields $1.00×1.254 = $2.4414…, and compounding monthly yields $1.00×(1.0833…)12 = $2.613035….

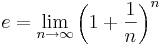

Bernoulli noticed that this sequence approaches a limit (the force of interest) for more and smaller compounding intervals. Compounding weekly yields $2.692597…, while compounding daily yields $2.714567…, just two cents more. Using n as the number of compounding intervals, with interest of 1/n in each interval, the limit for large n is the number that came to be known as e; with continuous compounding, the account value will reach $2.7182818…. More generally, an account that starts at $1, and yields (1+R) dollars at simple interest, will yield eR dollars with continuous compounding.

Bernoulli trials

The number e itself also has applications to probability theory, where it arises in a way not obviously related to exponential growth. Suppose that a gambler plays a slot machine that pays out with a probability of one in n and plays it n times. Then, for large n (such as a million) the probability that the gambler will win nothing at all is (approximately) 1⁄e.

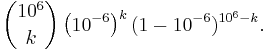

This is an example of a Bernoulli trials process. Each time the gambler plays the slots, there is a one in one million chance of winning. Playing one million times is modelled by the binomial distribution, which is closely related to the binomial theorem. The probability of winning k times out of a million trials is;

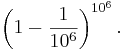

In particular, the probability of winning zero times (k=0) is

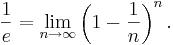

This is very close to the following limit for 1⁄e:

Derangements

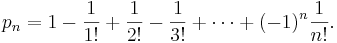

Another application of e, also discovered in part by Jacob Bernoulli along with Pierre Raymond de Montmort is in the problem of derangements, also known as the hat check problem.[5] Here n guests are invited to a party, and at the door each guest checks his hat with the butler who then places them into labeled boxes. But the butler does not know the name of the guests, and so must put them into boxes selected at random. The problem of de Montmort is: what is the probability that none of the hats gets put into the right box. The answer is:

As the number n of guests tends to infinity, pn approaches 1⁄e. Furthermore, the number of ways the hats can be placed into the boxes so that none of the hats is in the right box is exactly n! ⁄e, rounded to the nearest integer.[6]

Asymptotics

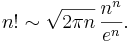

The number e occurs naturally in connection with many problems involving asymptotics. A prominent example is Stirling's formula for the asymptotics of the factorial function, in which both the numbers e and π enter:

A particular consequence of this is

e in calculus

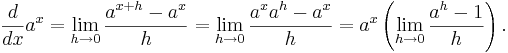

The principal motivation for introducing the number e, particularly in calculus, is to perform differential and integral calculus with exponential functions and logarithms.[7] A general exponential function y=ax has derivative given as the limit:

The limit on the right-hand side is independent of the variable x: it depends only on the base a. When the base is e, this limit is equal to one, and so e is symbolically defined by the equation:

Consequently, the exponential function with base e is particularly suited to doing calculus. Choosing e, as opposed to some other number, as the base of the exponential function makes calculations involving the derivative much simpler.

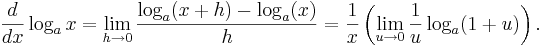

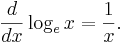

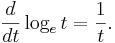

Another motivation comes from considering the base-a logarithm.[8] Considering the definition of the derivative of logax as the limit:

Once again, there is an undetermined limit which depends only on the base a, and if that base is e, the limit is one. So symbolically,

The logarithm in this special base is called the natural logarithm (often represented as "ln"), and it also behaves well under differentiation since there is no undetermined limit to carry through the calculations.

There are thus two ways in which to select a special number a=e. One way is to set the derivative of the exponential function ax to ax. The other way is to set the derivative of the base a logarithm to 1/x. In each case, one arrives at a convenient choice of base for doing calculus. In fact, these two bases are actually the same, the number e.

Alternative characterizations

- See also: Representations of e

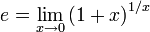

Other characterizations of e are also possible: one is as the limit of a sequence, another is as the sum of an infinite series, and still others rely on integral calculus. So far, the following two (equivalent) properties have been introduced:

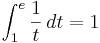

1. The number e is the unique positive real number such that

2. The number e is the unique positive real number such that

The following three characterizations can be proven equivalent:

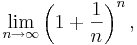

3. The number e is the limit

Similarly:

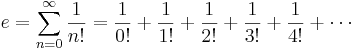

4. The number e is the sum of the infinite series

where n! is the factorial of n.

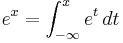

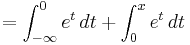

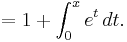

5. The number e is the unique positive real number such that

.

.

Properties

Calculus

As in the motivation, the exponential function f(x) = ex is important in part because it is the unique nontrivial function (up to multiplication by a constant) which is its own derivative

and therefore its own antiderivative as well:

Exponential-like functions

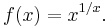

The number x = e is where the global maximum occurs for the function:

More generally, x = n√e is where the global maximum occurs for the function

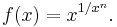

The infinite tetration

converges only if e−e ≤ x ≤ e1/e, due to a theorem of Leonhard Euler.

Number theory

The real number e is irrational (see proof that e is irrational), and furthermore is transcendental (Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem). It was the first number to be proved transcendental without having been specifically constructed for this purpose (compare with Liouville number); the proof was given by Charles Hermite in 1873. It is conjectured to be normal.

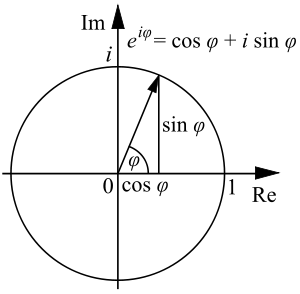

Complex numbers

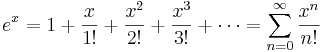

The exponential function ex may be written as a Taylor series

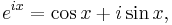

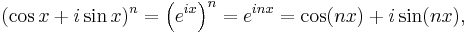

Because this series keeps many important properties for ex even when x is complex, it is commonly used to extend the definition of ex to the complex numbers. This, with the Taylor series for sin and cos x, allows one to derive Euler's formula:

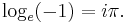

which holds for all x. The special case with x = π is known as Euler's identity:

Consequently,

from which it follows that, in the principal branch of the logarithm,

Furthermore, using the laws for exponentiation,

which is de Moivre's formula.

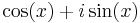

The case,

is commonly referred to as Cis(x).

Differential equations

The general function

is the solution to the differential equation:

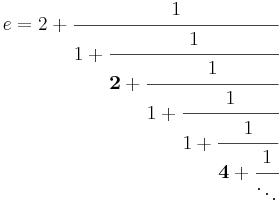

Representations

The number e can be represented as a real number in a variety of ways: as an infinite series, an infinite product, a continued fraction, or a limit of a sequence. The chief among these representations, particularly in introductory calculus courses is the limit

given above, as well as the series

given by evaluating the above power series for ex at x=1.

Still other less common representations are also available. For instance, e can be represented as an infinite simple continued fraction:

Or, in a more compact form (sequence A003417 in OEIS):

which can be written more harmoniously by allowing zero:[9]

Many other series, sequence, continued fraction, and infinite product representations of e have also been developed.

Stochastic representations

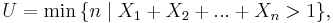

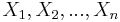

In addition to the deterministic analytical expressions for representation of e, as described above, there are some stochastic protocols for estimation of e. In one such protocol, random samples  of size n from the uniform distribution on (0, 1) are used to approximate e. If

of size n from the uniform distribution on (0, 1) are used to approximate e. If

then the expectation of U is e:  .[10][11] Thus sample averages of U variables will approximate e.

.[10][11] Thus sample averages of U variables will approximate e.

Known digits

The number of known digits of e has increased dramatically during the last decades. This is due both to the increase of performance of computers as well as to algorithmic improvements.[12][13]

| Date | Decimal digits | Computation performed by |

|---|---|---|

| 1748 | 18[14] | Leonhard Euler |

| 1853 | 137 | William Shanks |

| 1871 | 205 | William Shanks |

| 1884 | 346 | J. M. Boorman |

| 1946 | 808 | ? |

| 1949 | 2,010 | John von Neumann (on the ENIAC) |

| 1961 | 100,265 | Daniel Shanks & John W. Wrench |

| 1981 | 116,000 | Steve Wozniak (on the Apple II[15]) |

| 1994 | 10,000,000 | Robert Nemiroff & Jerry Bonnell |

| May 1997 | 18,199,978 | Patrick Demichel |

| August 1997 | 20,000,000 | Birger Seifert |

| September 1997 | 50,000,817 | Patrick Demichel |

| February 1999 | 200,000,579 | Sebastian Wedeniwski |

| October 1999 | 869,894,101 | Sebastian Wedeniwski |

| November 21 1999 | 1,250,000,000 | Xavier Gourdon |

| July 10 2000 | 2,147,483,648 | Shigeru Kondo & Xavier Gourdon |

| July 16 2000 | 3,221,225,472 | Colin Martin & Xavier Gourdon |

| August 2 2000 | 6,442,450,944 | Shigeru Kondo & Xavier Gourdon |

| August 16 2000 | 12,884,901,000 | Shigeru Kondo & Xavier Gourdon |

| August 21 2003 | 25,100,000,000 | Shigeru Kondo & Xavier Gourdon |

| September 18 2003 | 50,100,000,000 | Shigeru Kondo & Xavier Gourdon |

| April 27 2007 | 100,000,000,000 | Shigeru Kondo & Steve Pagliarulo |

In computer culture

In contemporary internet culture, individuals and organizations frequently pay homage to the number e.

For example, in the IPO filing for Google, in 2004, rather than a typical round-number amount of money, the company announced its intention to raise $2,718,281,828, which is e billion dollars to the nearest dollar. Google was also responsible for a mysterious billboard[16] that appeared in the heart of Silicon Valley, and later in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Seattle, Washington; and Austin, Texas. It read {first 10-digit prime found in consecutive digits of e}.com (now defunct). Solving this problem and visiting the advertised web site led to an even more difficult problem to solve, which in turn leads to Google Labs where the visitor is invited to submit a resume.[17] The first 10-digit prime in e is 7427466391, which starts as late as at the 99th digit.[18] (A random stream of digits has a 98.4% chance of starting a 10-digit prime sooner.)

In another instance, the eminent computer scientist Donald Knuth let the version numbers of his program METAFONT approach e. The versions are 2, 2.7, 2.71, 2.718, and so forth.

Notes

- ↑ Keisler, H.J. Derivatives of Exponential Functions and the Number e

- ↑ Keisler, H.J. General Solution of First Order Differential Equation

- ↑ Howard Whitley Eves (1969). An Introduction to the History of Mathematics. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. http://books.google.com/books?id=LIsuAAAAIAAJ&q=%22important+numbers+in+mathematics%22&dq=%22important+numbers+in+mathematics%22&pgis=1.

- ↑ O'Connor, J.J., and Roberson, E.F.; The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive: "The number e"; University of St Andrews Scotland (2001)

- ↑ Grinstead, C.M. and Snell, J.L. Introduction to probability theory (published online under the GFDL), p. 85.

- ↑ Knuth (1997) The Art of Computer Programming Volume I, Addison-Wesley, p. 183.

- ↑ See, for instance, Kline, M. (1998) Calculus: An intuitive and physical approach, Dover, section 12.3 "The Derived Functions of Logarithmic Functions."

- ↑ This is the approach taken by Klein (1998).

- ↑ Hofstadter, D. R., "Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought" Basic Books (1995)

- ↑ Russell, K. G. (1991) Estimating the Value of e by Simulation The American Statistician, Vol. 45, No. 1. (Feb., 1991), pp. 66-68.

- ↑ Dinov, ID (2007) Estimating e using SOCR simulation, SOCR Hands-on Activities (retrieved December 26, 2007).

- ↑ Sebah, P. and Gourdon, X.; The constant e and its computation

- ↑ Gourdon, X.; Reported large computations with PiFast

- ↑ New Scientist 21st July 2007 p.40

- ↑ Byte Magazine Vol 6, Issue 6 (June 1981) p.392) "The Impossible Dream: Computing e to 116,000 places with a Personal Computer"

- ↑ First 10-digit prime found in consecutive digits of e - Brain Tags

- ↑ Shea, Andrea. "Google Entices Job-Searchers with Math Puzzle", NPR. Retrieved on 2007-06-09.

- ↑ Kazmierczak, Marcus (2004-07-29). "Math : Google Labs Problems". mkaz.com. Retrieved on 2007-06-09.

References

- Maor, Eli; e: The Story of a Number, ISBN 0-691-05854-7

External links

- The number e to 1 million places and 2 and 5 million places

- Earliest Uses of Symbols for Constants

- e the EXPONENTIAL - the Magic Number of GROWTH - Keith Tognetti, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia

- An Intuitive Guide To Exponential Functions & e

- "The story of e", by Robin Wilson at Gresham College, 28 February 2007 (available for audio and video download)

- Class Library for Numbers (part of the GiNaC distribution) includes example code for computing e to arbitrary precision.

- The SOCR resource provides a hands-on activity and an interactive Java applet (Uniform E-Estimate Experiment) for computing e using a simulation based on uniform distribution.

![e = \lim_{n\to\infty} \frac{n}{\sqrt[n]{n!}}.](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/9c678d256067a90ef02d482bac3daa8f.png)

![e = [[2; 1, \textbf{2}, 1, 1, \textbf{4}, 1, 1, \textbf{6}, 1, 1, \textbf{8}, 1, \ldots,1, \textbf{2n}, 1,\ldots]], \,](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/d5bf248824a983d083b159a0c72f1bee.png)

![e = [[ 1 , \textbf{0} , 1 , 1, \textbf{2}, 1, 1, \textbf{4}, 1 , 1 , \textbf{6}, 1, \ldots]]. \,](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/08e936b155dac0a6c51c43dee64c429b.png)