.NET Framework

| Developed by | Microsoft |

|---|---|

| Latest release | 3.5.30729.1 (3.5 SP1) / 11 August 2008 |

| OS | Windows NT 4.0, Windows 98 and above |

| Type | System platform |

| License | MS-EULA, BCL under Microsoft Reference License[1] |

| Website | http://www.microsoft.com/net/ |

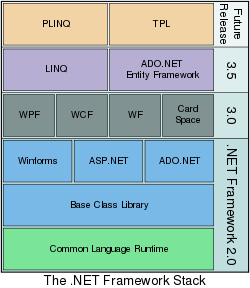

The Microsoft .NET Framework is a software technology that is available with several Microsoft Windows operating systems. It includes a large library of pre-coded solutions to common programming problems and a virtual machine that manages the execution of programs written specifically for the framework. The .NET Framework is a key Microsoft offering and is intended to be used by most new applications created for the Windows platform.

The pre-coded solutions that form the framework's Base Class Library cover a large range of programming needs in a number of areas, including user interface, data access, database connectivity, cryptography, web application development, numeric algorithms, and network communications. The class library is used by programmers, who combine it with their own code to produce applications.

Programs written for the .NET Framework execute in a software environment that manages the program's runtime requirements. Also part of the .NET Framework, this runtime environment is known as the Common Language Runtime (CLR). The CLR provides the appearance of an application virtual machine so that programmers need not consider the capabilities of the specific CPU that will execute the program. The CLR also provides other important services such as security, memory management, and exception handling. The class library and the CLR together compose the .NET Framework.

Version 3.0 of the .NET Framework is included with Windows Server 2008 and Windows Vista. The current version of the framework can also be installed on Windows XP and the Windows Server 2003 family of operating systems.[2] A reduced "Compact" version of the .NET Framework is also available on Windows Mobile platforms, including smartphones.

Contents |

Principal design features

- Interoperability

- Because interaction between new and older applications is commonly required, the .NET Framework provides means to access functionality that is implemented in programs that execute outside the .NET environment. Access to COM components is provided in the System.Runtime.InteropServices and System.EnterpriseServices namespaces of the framework; access to other functionality is provided using the P/Invoke feature.

- Common Runtime Engine

- The Common Language Runtime (CLR) is the virtual machine component of the .NET framework. All .NET programs execute under the supervision of the CLR, guaranteeing certain properties and behaviors in the areas of memory management, security, and exception handling.

- Base Class Library

- The Base Class Library (BCL), part of the Framework Class Library (FCL), is a library of functionality available to all languages using the .NET Framework. The BCL provides classes which encapsulate a number of common functions, including file reading and writing, graphic rendering, database interaction and XML document manipulation.

- Simplified Deployment

- Installation of computer software must be carefully managed to ensure that it does not interfere with previously installed software, and that it conforms to security requirements. The .NET framework includes design features and tools that help address these requirements.

- Security

- The design is meant to address some of the vulnerabilities, such as buffer overflows, that have been exploited by malicious software. Additionally, .NET provides a common security model for all applications.

- Portability

- The design of the .NET Framework allows it to theoretically be platform agnostic, and thus cross-platform compatible. That is, a program written to use the framework should run without change on any type of system for which the framework is implemented. Microsoft's commercial implementations of the framework cover Windows, Windows CE, and the Xbox 360.[3] In addition, Microsoft submits the specifications for the Common Language Infrastructure (which includes the core class libraries, Common Type System, and the Common Intermediate Language),[4][5][6] the C# language,[7] and the C++/CLI language[8] to both ECMA and the ISO, making them available as open standards. This makes it possible for third parties to create compatible implementations of the framework and its languages on other platforms.

Architecture

Common Language Infrastructure

The core aspects of the .NET framework lie within the Common Language Infrastructure, or CLI. The purpose of the CLI is to provide a language-neutral platform for application development and execution, including functions for exception handling, garbage collection, security, and interoperability. Microsoft's implementation of the CLI is called the Common Language Runtime or CLR.

Assemblies

The intermediate CIL code is housed in .NET assemblies. As mandated by specification, assemblies are stored in the Portable Executable (PE) format, common on the Windows platform for all DLL and EXE files. The assembly consists of one or more files, one of which must contain the manifest, which has the metadata for the assembly. The complete name of an assembly (not to be confused with the filename on disk) contains its simple text name, version number, culture, and public key token. The public key token is a unique hash generated when the assembly is compiled, thus two assemblies with the same public key token are guaranteed to be identical from the point of view of the framework. A private key can also be specified known only to the creator of the assembly and can be used for strong naming and to guarantee that the assembly is from the same author when a new version of the assembly is compiled (required to add an assembly to the Global Assembly Cache).

Metadata

All CLI is self-describing through .NET metadata. The CLR checks the metadata to ensure that the correct method is called. Metadata is usually generated by language compilers but developers can create their own metadata through custom attributes. Metadata contains information about the assembly, and is also used to implement the reflective programming capabilities of .NET Framework.

Security

.NET has its own security mechanism with two general features: Code Access Security (CAS), and validation and verification. Code Access Security is based on evidence that is associated with a specific assembly. Typically the evidence is the source of the assembly (whether it is installed on the local machine or has been downloaded from the intranet or Internet). Code Access Security uses evidence to determine the permissions granted to the code. Other code can demand that calling code is granted a specified permission. The demand causes the CLR to perform a call stack walk: every assembly of each method in the call stack is checked for the required permission; if any assembly is not granted the permission a security exception is thrown.

When an assembly is loaded the CLR performs various tests. Two such tests are validation and verification. During validation the CLR checks that the assembly contains valid metadata and CIL, and whether the internal tables are correct. Verification is not so exact. The verification mechanism checks to see if the code does anything that is 'unsafe'. The algorithm used is quite conservative; hence occasionally code that is 'safe' does not pass. Unsafe code will only be executed if the assembly has the 'skip verification' permission, which generally means code that is installed on the local machine.

.NET Framework uses appdomains as a mechanism for isolating code running in a process. Appdomains can be created and code loaded into or unloaded from them independent of other appdomains. This helps increase the fault tolerance of the application, as faults or crashes in one appdomain do not affect rest of the application. Appdomains can also be configured independently with different security privileges. This can help increase the security of the application by isolating potentially unsafe code. The developer, however, has to split the application into subdomains; it is not done by the CLR.

Class library

| Namespaces in the BCL[9] |

|---|

| System |

| System. CodeDom |

| System. Collections |

| System. Diagnostics |

| System. Globalization |

| System. IO |

| System. Resources |

| System. Text |

| System. Text.RegularExpressions |

- See also: Base Class Library and Framework Class Library

Microsoft .NET Framework includes a set of standard class libraries. The class library is organized in a hierarchy of namespaces. Most of the built in APIs are part of either System.* or Microsoft.* namespaces. It encapsulates a large number of common functions, such as file reading and writing, graphic rendering, database interaction, and XML document manipulation, among others. The .NET class libraries are available to all .NET languages. The .NET Framework class library is divided into two parts: the Base Class Library and the Framework Class Library.

The Base Class Library (BCL) includes a small subset of the entire class library and is the core set of classes that serve as the basic API of the Common Language Runtime.[9] The classes in mscorlib.dll and some of the classes in System.dll and System.core.dll are considered to be a part of the BCL. The BCL classes are available in both .NET Framework as well as its alternative implementations including .NET Compact Framework, Microsoft Silverlight and Mono.

The Framework Class Library (FCL) is a superset of the BCL classes and refers to the entire class library that ships with .NET Framework. It includes an expanded set of libraries, including WinForms, ADO.NET, ASP.NET, Language Integrated Query, Windows Presentation Foundation, Windows Communication Foundation among others. The FCL is much larger in scope than standard libraries for languages like C++, and comparable in scope to the standard libraries of Java.

Memory management

The .NET Framework CLR frees the developer from the burden of managing memory (allocating and freeing up when done); instead it does the memory management itself. To this end, the memory allocated to instantiations of .NET types (objects) is done contiguously[10] from the managed heap, a pool of memory managed by the CLR. As long as there exists a reference to an object, which might be either a direct reference to an object or via a graph of objects, the object is considered to be in use by the CLR. When there is no reference to an object, and it cannot be reached or used, it becomes garbage. However, it still holds on to the memory allocated to it. .NET Framework includes a garbage collector which runs periodically, on a separate thread from the application's thread, that enumerates all the unusable objects and reclaims the memory allocated to them.

The .NET Garbage Collector (GC) is a non-deterministic, compacting, mark-and-sweep garbage collector. The GC runs only when a certain amount of memory has been used or there is enough pressure for memory on the system. Since it is not guaranteed when the conditions to reclaim memory are reached, the GC runs are non-deterministic. Each .NET application has a set of roots, which are pointers to objects on the managed heap (managed objects). These include references to static objects and objects defined as local variables or method parameters currently in scope, as well as objects referred to by CPU registers.[10] When the GC runs, it pauses the application, and for each object referred to in the root, it recursively enumerates all the objects reachable from the root objects and marks them as reachable. It uses .NET metadata and reflection to discover the objects encapsulated by an object, and then recursively walk them. It then enumerates all the objects on the heap (which were initially allocated contiguously) using reflection. All objects not marked as reachable are garbage.[10] This is the mark phase.[11] Since the memory held by garbage is not of any consequence, it is considered free space. However, this leaves chunks of free space between objects which were initially contiguous. The objects are then compacted together, by using memcpy[11] to copy them over to the free space to make them contiguous again.[10] Any reference to an object invalidated by moving the object is updated to reflect the new location by the GC.[11] The application is resumed after the garbage collection is over.

The GC used by .NET Framework is actually generational.[12] Objects are assigned a generation; newly created objects belong to Generation 0. The objects that survive a garbage collection are tagged as Generation 1, and the Generation 1 objects that survive another collection are Generation 2 objects. The .NET Framework uses up to Generation 2 objects.[12] Higher generation objects are garbage collected less frequently than lower generation objects. This helps increase the efficiency of garbage collection, as older objects tend to have a larger lifetime than newer objects.[12] Thus, by removing older (and thus more likely to survive a collection) objects from the scope of a collection run, fewer objects need to be checked and compacted.[12]

Standardization and licensing

In August 2000, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, and Intel worked to standardize CLI and the C# programming language. By December 2001, both were ratified ECMA standards (ECMA 335 and ECMA 334). ISO followed in April 2003 - the current version of the ISO standards are ISO/IEC 23271:2006 and ISO/IEC 23270:2006.[13][14]

While Microsoft and their partners hold patents for the CLI and C#, ECMA and ISO require that all patents essential to implementation be made available under "reasonable and non-discriminatory terms". In addition to meeting these terms, the companies have agreed to make the patents available royalty-free.

However, this does not apply for the part of the .NET Framework which is not covered by the ECMA/ISO standard, which includes Windows Forms, ADO.NET, and ASP.NET. Patents that Microsoft holds in these areas may deter non-Microsoft implementations of the full framework.

On 3 October 2007, Microsoft announced that much of the source code for the .NET Framework Base Class Library (including ASP.NET, ADO.NET, and Windows Presentation Foundation) was to have been made available with the final release of Visual Studio 2008 towards the end of 2007 under the shared source Microsoft Reference License.[1] The source code for other libraries including Windows Communication Foundation (WCF), Windows Workflow Foundation (WF), and Language Integrated Query (LINQ) were to be added in future releases. Being released under the non Open-source Microsoft Reference License means this source code is made available for debugging purpose only, primarily to support integrated debugging of the BCL in Visual Studio.

Versions

Microsoft started development on the .NET Framework in the late 1990s originally under the name of Next Generation Windows Services (NGWS). By late 2000 the first beta versions of .NET 1.0 were released.[15]

| Version | Version Number | Release Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.0.3705.0 | 2002-01-05 |

| 1.1 | 1.1.4322.573 | 2003-04-01 |

| 2.0 | 2.0.50727.42 | 2005-11-07 |

| 3.0 | 3.0.4506.30 | 2006-11-06 |

| 3.5 | 3.5.21022.8 | 2007-11-09 |

A more complete listing of the releases of the .NET Framework may be found on the .NET Framework version list.

.NET Framework 1.0

This is the first release of the .NET Framework, released on 13 February 2002 and available for Windows 98, NT 4.0, 2000, and XP. Mainstream support by Microsoft for this version ended 10 July 2007, and extended support ends 14 July 2009.[16]

.NET Framework 1.1

This is the first major .NET Framework upgrade. It is available on its own as a redistributable package or in a software development kit, and was published on 3 April 2003. It is also part of the second release of Microsoft Visual Studio .NET (released as Visual Studio .NET 2003). This is the first version of the .NET Framework to be included as part of the Windows operating system, shipping with Windows Server 2003. Mainstream support for .NET Framework 1.1 ended on 14 October 2008, and extended support ends on 8 October 2013. Since .NET 1.1 is a component of Windows Server 2003, extended support for .NET 1.1 on Server 2003 will run out with that of the OS - currently 30 June 2013.

Changes in 1.1 on comparison with 1.0

- Built-in support for mobile ASP.NET controls. Previously available as an add-on for .NET Framework, now part of the framework.

- Security changes - enable Windows Forms assemblies to execute in a semi-trusted manner from the Internet, and enable Code Access Security in ASP.NET applications.

- Built-in support for ODBC and Oracle databases. Previously available as an add-on for .NET Framework 1.0, now part of the framework.

- .NET Compact Framework - a version of the .NET Framework for small devices.

- Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) support.

- Numerous API changes.

.NET Framework 2.0

Released with Visual Studio 2005, Microsoft SQL Server 2005, and BizTalk 2006.

- The 2.0 Redistributable Package can be downloaded for free from Microsoft, and was published on 2006-01-22.

- The 2.0 Software Development Kit (SDK) can be downloaded for free from Microsoft.

- It is included as part of Visual Studio 2005 and Microsoft SQL Server 2005.

- Version 2.0 is the last version with support for Windows 2000, Windows 98 and Windows Me.

- It shipped with Windows Server 2003 R2 (not installed by default).

Changes in 2.0 on comparison with 1.1

- Numerous API changes.

- A new hosting API for native applications wishing to host an instance of the .NET runtime. The new API gives a fine grain control on the behavior of the runtime with regards to multithreading, memory allocation, assembly loading and more (detailed reference). It was initially developed to efficiently host the runtime in Microsoft SQL Server, which implements its own scheduler and memory manager.

- Full 64-bit support for both the x64 and the IA64 hardware platforms.

- Language support for generics built directly into the .NET CLR.

- Many additional and improved ASP.NET web controls.

- New data controls with declarative data binding.

- New personalization features for ASP.NET, such as support for themes, skins and webparts.

- .NET Micro Framework - a version of the .NET Framework related to the Smart Personal Objects Technology initiative.

.NET Framework 3.0

.NET Framework 3.0, formerly called WinFX,[17] includes a new set of managed code APIs that are an integral part of Windows Vista and Windows Server 2008 operating systems. It is also available for Windows XP SP2 and Windows Server 2003 as a download. There are no major architectural changes included with this release; .NET Framework 3.0 uses the Common Language Runtime of .NET Framework 2.0.[18] Unlike the previous major .NET releases there was no .NET Compact Framework release made as a counterpart of this version.

.NET Framework 3.0 consists of four major new components:

- Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF), formerly code-named Avalon; a new user interface subsystem and API based on XML and vector graphics, which uses 3D computer graphics hardware and Direct3D technologies. See WPF SDK for developer articles and documentation on WPF.

- Windows Communication Foundation (WCF), formerly code-named Indigo; a service-oriented messaging system which allows programs to interoperate locally or remotely similar to web services.

- Windows Workflow Foundation (WF) allows for building of task automation and integrated transactions using workflows.

- Windows CardSpace, formerly code-named InfoCard; a software component which securely stores a person's digital identities and provides a unified interface for choosing the identity for a particular transaction, such as logging in to a website.

.NET Framework 3.5

Version 3.5 of the .NET Framework was released on 19 November 2007, but it is not included with Windows Server 2008. As with .NET Framework 3.0, version 3.5 uses the CLR of version 2.0. In addition, it installs .NET Framework 2.0 SP1, .NET Framework 2.0 SP2 (with 3.5 SP1) and .NET Framework 3.0 SP1, which adds some methods and properties to the BCL classes in version 2.0 which are required for version 3.5 features such as Language Integrated Query (LINQ). These changes do not affect applications written for version 2.0, however.[19]

As with previous versions, a new .NET Compact Framework 3.5 was released in tandem with this update in order to provide support for additional features on Windows Mobile and Windows Embedded CE devices.

The source code of the Base Class Library in this version has been partially released (for debugging reference only) under the Microsoft Reference Source License.[1]

Changes since version 3.0

- New language features in C# 3.0 and VB.NET 9.0 compiler

- Adds support for expression trees and lambda methods

- Extension methods

- Expression trees to represent high-level source code at runtime.[20]

- Anonymous types with static type inference

- Language Integrated Query (LINQ) along with its various providers

- LINQ to Objects

- LINQ to XML

- LINQ to SQL

- Paging support for ADO.NET

- ADO.NET synchronization API to synchronize local caches and server side datastores

- Asynchronous network I/O API[20]

- Peer-to-peer networking stack, including a managed PNRP resolver[21]

- Managed wrappers for Windows Management Instrumentation and Active Directory APIs[22]

- Enhanced WCF and WF runtimes, which let WCF work with POX and JSON data, and also expose WF workflows as WCF services.[23] WCF services can be made stateful using the WF persistence model.[20]

- Support for HTTP pipelining and syndication feeds.[23]

- ASP.NET AJAX is included

- New

System.CodeDomnamespace.

Service Pack 1

The .NET Framework 3.5 Service Pack 1 was released on August 11, 2008. This release adds new functionality and provides performance improvements in certain conditions,[24] especially with WPF where 20-45% improvements are expected. Two new data service components have been added, the ADO.NET Entity Framework and ADO.NET Data Services. Two new assemblies for web development, System.Web.Abstraction and System.Web.Routing, have been added; these are used in the upcoming ASP.NET MVC Framework and, reportedly, will be utilized in the future release of ASP.NET Forms applications. Service Pack 1 is included with SQL Server 2008 and Visual Studio 2008 Service Pack 1.

There is also a new variant of the .NET Framework, called the ".NET Framework Client Profile", which is 86% smaller than the full framework and only installs components relevant to desktop applications.[25]

.NET Framework 4.0

Microsoft announced the .NET Framework 4.0 on September 29, 2008. While full details about its feature set have yet to be released, some general information regarding the company's plans have been made public. One focus of this release is to improve support for parallel computing, which target multi-core or distributed systems.[26] To this end, they plan to include technologies like PLINQ (Parallel LINQ),[27] a parallel implementation of the LINQ engine, and Task Parallel Library, which exposes parallel constructs via method calls.[28] Microsoft has also stated that they plan to support a subset of the .NET Framework and ASP.NET with the "Server Core" variant of Windows Server 2008's successor.[29]

.NET vs. Java and Java EE

- See also: Comparison of the Java and .NET platforms and Comparison of C# and Java

The CLI and .NET languages such as C# and VB have many similarities to Sun's JVM and Java. They are strong competitors. Both are based on a virtual machine model that hides the details of the computer hardware on which their programs run. Both use their own intermediate byte-code, Microsoft calling theirs Common Intermediate Language (CIL; formerly MSIL) and Sun Java bytecode. On .NET the byte-code is always compiled before execution, either Just In Time (JIT) or in advance of execution using the ngen.exe utility. With Java the byte-code is either interpreted, compiled in advance, or compiled JIT. Both provide extensive class libraries that address many common programming requirements and address many security issues that are present in other approaches. The namespaces provided in the .NET Framework closely resemble the platform packages in the Java EE API Specification in style and invocation.

.NET in its complete form (Microsoft's implementation) is only available on Windows platforms and partially available on Linux and Macintosh,[30][31][32] whereas Java is fully available on many platforms.[33] From its beginning .NET has supported multiple programming languages and at its core remains platform agnostic and standardized so that other vendors can implement it on other platforms (although Microsoft's implementation only targets Windows, Windows CE, and Xbox platforms). The Java platform was initially built to support only the Java language on many operating system platforms under the slogan "Write once, run anywhere." Other programming languages have been implemented on the Java Virtual Machine[34] but are less widely used (see JVM languages).

Sun's reference implementation of Java (including the class library, the compiler, the virtual machine, and the various tools associated with the Java Platform) is open source under the GNU GPL license with Classpath exception.[35] The source code for the .NET framework base class library is available under the Microsoft Reference License. [36] [37]

The third-party Mono Project, sponsored by Novell, has been developing an open source implementation of the ECMA standards that define the .NET Framework, as well as most of the other non-ECMA standardized libraries in Microsoft's .NET. The Mono implementation is meant to run on Linux, Solaris, Mac OS X, BSD, HP-UX, and Windows platforms. Mono includes the CLR, the class libraries, and compilers for C# and VB.NET. The current version supports all the APIs in version 2.0 of Microsoft's .NET. Full support exists for c# 3.0 LINQ to Objects and LINQ to Xml. [38]

Criticism

Some concerns and criticism relating to .NET include:

- Applications running in a managed environment such as the Microsoft framework's CLR or Java's JVM tend to require more system resources than similar applications that access machine resources more directly. Some applications, however, have been shown to perform better in .NET than in their native version. This could be due to the runtime optimizations made possible by such an environment, the use of relatively well-performing functions in the .NET framework, just-in-time compilation of managed code, or other aspects of the CLR.[39][40]

- As JIT languages can be more easily reverse-engineered than native code to algorithms used by an application there is concern over possible loss of trade secrets and the bypassing of license control mechanisms. Many obfuscation techniques already developed can help to prevent this; Microsoft's Visual Studio 2005 (and newer) includes such a tool.

- In a managed environment such as the Microsoft framework's CLR or typical Java JVMs the regularly occurring garbage collection for reclaiming memory suspends execution of the application for an unpredictable lapse of time (typically no more than a few milliseconds, but in memory-constrained systems can be much longer). This makes such environments unsuitable for some applications such as those that must respond to events with predictable timing (see real-time computing).

- Since the framework is not pre-installed on older versions of Windows an application that requires it must verify that it is present, and if it is not, guide the user to install it. This requirement may deter some from using the application.

- Newer versions of the framework (3.5 and up) are not pre-installed on any versions of the Windows operating system. Some developers have expressed concerns about the large size (around 54 MB for end-users with .NET 3.0 and 197 MB with .NET 3.5) and reliability of .NET framework runtime installers for end-users. The first service pack for version 3.5 mitigates this concern by offering a lighter-weight client-only subset of the full .NET Framework.

- The .NET framework currently does not provide support for calling Streaming SIMD Extensions (SSE) via managed code. Streaming SIMD Extensions has been available since the introduction of the Pentium III.

Alternative implementations

The Microsoft .NET Framework is the predominant implementation of .NET technologies. Other implementations for parts of the framework exist. Since the runtime engine is described by an ECMA/ISO specification, other implementations of it are unencumbered by copyright issues. It is more difficult to develop alternatives to the base class library (BCL), which is not described by an open standard, and may be subject to copyright restrictions. Additionally, parts of the BCL have Windows-specific functionality and behavior, so implementation on non-Windows platforms can be problematic.

Some alternative implementations of parts of the framework are listed here.

- Microsoft's Shared Source Common Language Infrastructure is a non-free shared source implementation of the CLR component of the .NET Framework. However, the last version only runs on Microsoft Windows XP SP2, and does not contain all features of version 2.0 of the .NET Framework.

- Portable.NET (part of DotGNU) provides an implementation of the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI), portions of the .NET Base Class Library (BCL), and a C# compiler. It supports a variety of CPUs and operating systems.

- Mono is an implementation of the CLI and portions of the .NET Base Class Library (BCL), and provides additional functionality. It is dual-licensed under free software and proprietary software licenses. Mono is being developed by Novell, Inc. It includes support for ASP.NET, ADO.NET, and evolving support for Windows Forms libraries. It also includes a C# compiler, and a VB.NET compiler is in pre-beta form.

- CrossNet is an implementation of the CLI and portions of the .NET Base Class Library (BCL). It is free software. It parses .NET assemblies and generates unmanaged C++ code that can be compiled and linked within any ANSI C++ application on any platform.

- .NET for Symbian .NET Compact Framework implementation for Symbian (S60)

See also

- Comparison of the Java and .NET platforms

- Common Language Infrastructure (CLI Languages)

- Mono (software)

- COM Interop

- Components and libraries

- Base Class Library

- ADO.NET

- ASP.NET

- Silverlight

- Microsoft Enterprise Library - A collection of supplemental libraries for .NET.

- Web Services Enhancements

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Scott Guthrie. "Releasing the Source Code for the NET Framework". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ Microsoft. "Microsoft .NET Framework 3.5 Administrator Deployment Guide". Retrieved on 2008-06-26.

- ↑ Microsoft has also previously released implementations of .NET 1.0 that could run on some Unix-based platforms such as FreeBSD and Mac OS X, but license restrictions limited these to educational use only, and they are no more available since .NET 1.1

- ↑ "ECMA 335 - Standard ECMA-335 Common Language Infrastructure (CLI)". ECMA (2006-06-01). Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ ISO/IEC 23271:2006

- ↑ "Technical Report TR/84 Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) - Information Derived from Partition IV XML File". ECMA (2006-06-01).

- ↑ "ECMA-334 C# Language Specification". ECMA (2006-06-01).

- ↑ "Standard ECMA-372 C++/CLI Language Specification". ECMA (2005-12-01).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Base Class Library". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Garbage Collection: Automatic Memory Management in the Microsoft .NET Framework". Archived from the original on 2007-07-03. Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Garbage collection in .NET". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "Garbage Collection—Part 2: Automatic Memory Management in the Microsoft .NET Framework". Archived from the original on 2007-06-26. Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ ISO/IEC 23271:2006 - Information technology - Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) Partitions I to VI

- ↑ ISO/IEC 23270:2006 - Information technology - Programming languages - C#

- ↑ "Framework Versions".

- ↑ "Microsoft Product Lifecycle Search". Microsoft. Retrieved on 2008-01-25.

- ↑ WinFX name change announcement

- ↑ ".NET Framework 3.0 Versioning and Deployment Q&A". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ "Catching RedBits differences in .NET 2.0 and .NET 2.0SP1". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "What's New in the .NET Framework 3.5". Retrieved on 2008-03-31.

- ↑ Kevin Hoffman. "Orcas' Hidden Gem - The managed PNRP stack". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ ".NET Framework 3.5". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Matt Winkle. "WCF and WF in "Orcas"". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ "Visual Studio 2008 Service Pack 1 and .NET Framework 3.5 Service Pack 1". Retrieved on 2008-09-07.

- ↑ Justin Van Patten (May 21, 2008). ".NET Framework Client Profile". BCL Team Blog. MSDN Blogs. Retrieved on 2008-09-30.

- ↑ S. Somasegar. "The world of multi and many cores". Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ "Parallel LINQ: Running Queries On Multi-Core Processors". Retrieved on 2008-06-02.

- ↑ "Parallel Performance: Optimize Managed Code For Multi-Core Machines". Retrieved on 2008-06-02.

- ↑ "PDC2008 Sessions Overview". Microsoft (28 May 2008). Retrieved on 2008-05-28.

- ↑ .Net Framework 1.0 Redistributable Requirements MSDN, Accessed 22 April 2007

- ↑ .Net Framework 1.1 Redistributable Requirements MSDN, Accessed 22 April 2007

- ↑ .Net Framework 2.0 Redistributable Requirements MSDN, Accessed 22 April 2007

- ↑ JRE 5.0 Installation Notes Sun Developer Network, Access 22 April 2007

- ↑ "Languages for the Java VM". Retrieved on 2008-07-07.

- ↑ "Free and Open Source Java". Sun.com. Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ "Releasing the source code for the .Net framework libraries". Scott Guthrie - Microsoft.

- ↑ "Microsoft Reference License". Microsoft.

- ↑ "FAQ: General". Mono (2006-12-20). Retrieved on 2008-06-01.

- ↑ The PHP Language Compiler for the .NET Framework

- ↑ "IronPython: A fast Python implementation for .NET and Mono". Archived from the original on 2004-04-16.

ASP.Net By Vinay Rajgure

External links

- Microsoft .NET new logo and branding

- .NET Framework Developer Center

- .NET Framework Tutorial

- Windows Vista Developer Center

- BCL Team Blog

- Interview on Channel 9 with Jason Zander, general manager of the .NET Framework team, about .NET Fx 3.5; streaming wmv file.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||