Zidovudine

|

|

|

|

|

Zidovudine

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

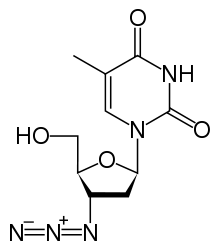

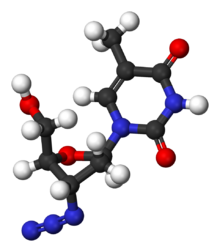

| 1-[(2R,4S,5S)-4-azido-5-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]- 5-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | J05 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C10H13N5O4 |

| Mol. mass | 267.242 g/mol |

| SMILES | & |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | near complete absoprtion, following first-pass metabolism systemic availability 65% (range 52 to 75%) |

| Protein binding | 30 to 38% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Half life | 0.5 to 3 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. |

C(US) |

| Legal status | |

| Routes | Oral |

Zidovudine (INN) or azidothymidine (AZT) (also called ZDV) is a nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), a type of antiretroviral drug. It was the first approved treatment for HIV. It is also sold under the names Retrovir and Retrovis, and as an ingredient in Combivir and Trizivir. It is an analog of thymidine.

Contents |

History

Zidovudine was the first drug approved for the treatment of AIDS and HIV infection. Jerome Horwitz of Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute and Wayne State University School of Medicine first synthesized AZT in 1964, under a US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant. AZT was originally intended to treat cancer, but was shelved after it proved ineffective in treating cancer in mice.[1]

In February 1985, Samuel Broder, Hiroaki Mitsuya, and Robert Yarchoan, three scientists in the National Cancer Institute (NCI), collaborating with Janet Rideout and several other scientists at Burroughs Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline), started working on it as an AIDS drug. After showing that this drug was an effective agent against HIV in vitro, the NCI team conducted the initial phase 1 clinical trial that provided evidence that it could increase CD4 counts in AIDS patients.

A placebo-controlled randomized trial of AZT was subsequently conducted by Burroughs-Wellcome, in which it was shown that AZT could prolong the life of patients with AIDS.[2] Burroughs Wellcome Co. filed for a patent on AZT in 1985. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug (via the then-new FDA accelerated approval system) for use against HIV, AIDS, and AIDS Related Complex (ARC, a now-defunct medical term for pre-AIDS illness) on March 20 1987, and then as a preventive treatment in 1990. It was initially administered in much higher dosages than today, typically 400 mg every four hours (even at night). However, the unavailability at that time of alternatives to treat AIDS affected the risk/benefit ratio, with the certain toxicity of HIV infection outweighing the risk of drug toxicity. One of AZT's side effects includes anemia, a common complaint in early trials.

Modern treatment regimens typically use lower dosages (e.g. 300 mg) two times a day. As of 1996, AZT, like other antiretroviral drugs, is almost always used as part of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). That is, it is combined with other drugs in order to prevent mutation of HIV into an AZT-resistant form.[3][4]

The crystal structure of AZT was reported by Alan Howie (Aberdeen University) in 1988.[5] In the solid state AZT forms a hydrogen bond network.

Prophylaxis

AZT may be used in combination with other antiretroviral medications to substantially reduce the risk of HIV infection following a significant exposure to the virus (such as a needle-stick injury involving blood or body fluids from an individual known to be infected with HIV).[6]

AZT is also recommended as part of a regimen to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV during pregnancy, labor and delivery.[7] With no treatment, approximately 25% of infants whose mothers are infected with HIV will become infected. AZT has been shown to reduce this risk to approximately 8% when given in a three-part regimen during pregnancy, delivery and to the infant for 6 weeks after birth.[8] Use of appropriate combinations of antiretroviral medications, cesarean section and avoidance of breast feeding can further reduce mother-child transmission of HIV to 1-2%.

Side effects

Common side effects of AZT include nausea, headache, changes in body fat, and discoloration of fingernails and toenails. More severe side effects include anemia and bone marrow suppression, which can be overcome using erythropoietin or darbepoetin treatments.23 These unwanted side effects might be caused by the sensitivity of the γ-DNA polymerase in the cell mitochondria. AZT has been shown to work additively or synergistically with many antiviral agents such as acyclovir and interferon; however, ribavirin decreases the antiviral effect of AZT. Drugs that inhibit hepatic glucuronidation, such as indomethacin, acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) and trimethoprim, decrease the elimination rate and increase the toxicity.[9]

Viral resistance

AZT does not destroy the HIV infection, but only delays the progression of the disease and the replication of virus, even at very high doses. During prolonged AZT treatment HIV has the ability to gain an increased resistance to AZT by mutation of the reverse transcriptase. A study showed that AZT could not impede the resumption of virus production, and eventually cells treated with AZT produced viruses as much as the untreated cells. To slow the development of resistance, physicians generally recommend that AZT be given in combination with another reverse transcriptase inhibitor and an antiretroviral from another group, such as a protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Mode of action

Like other reverse transcriptase inhibitors, AZT works by inhibiting the action of reverse transcriptase, the enzyme that HIV uses to make a DNA copy of its RNA. Reverse transcription is necessary for production of the viral double-stranded DNA, which is subsequently spliced into the genetic material of a target cell (where it is called a provirus).[10][11][12]

The azido group increases the lipophilic nature of AZT, allowing it to cross cell membranes easily by diffusion and thereby also to cross the blood-brain barrier. Cellular enzymes convert AZT into the effective 5'-triphosphate form. Studies have shown that the termination of the formed DNA chains is the specific factor in the inhibitory effect.

The triphosphate form also has some ability to inhibit cellular DNA polymerase, which is used by normal cells as part of cell division.[13][14][15] However, AZT has a 100- to 300-fold greater affinity for the HIV reverse transcriptase, as compared to the human DNA polymerase, accounting for its selective antiviral activity.[16] A special kind of cellular DNA polymerase that replicates the DNA in mitochondria is relatively more sensitive to inhibition by AZT, and this accounts for certain toxicities such as damage to cardiac and other muscles (also called myositis).[17][18][19][20][21]

Patent issues

AZT has been the target of some controversy due to the nature of the patent process.[22]

In 1991, Public Citizen filed a lawsuit claiming that the AZT/Zidovudine patent was invalid. The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled in 1992 in favour of Burroughs Wellcome, the licensee of the patent.[23] The court ruled that the challenge of the citizen group was not the correct approach to evaluate the underlying validity of the patent which was already being litigated in another suit. [24] In 2002, another lawsuit was filed over the patent by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

However, the patent expired in 2005 (placing AZT in the public domain), allowing other drug companies to manufacture and market generic AZT without having to pay GlaxoSmithKline any royalties. The U.S. FDA has since approved four generic forms of AZT for sale in the U.S.

Footnotes

- ↑ A Failure Led to Drug Against AIDS. Published in the New York Times on September 20 1986; accessed March 17 2008.

- ↑ Fischl MA, Richman DD, Grieco MH, Gottlieb MS, Volberding PA, Laskin OL, Leedom JM, Groopman JE, Mildvan D, Schooley RT, et al (1987). "The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.". N Engl J Med 317 (4): 185–91. PMID 3299089.

- ↑ De Clercq E (1994). "HIV resistance to reverse transcriptase inhibitors.". Biochem Pharmacol 47 (2): 155–69. doi:. PMID 7508227.

- ↑ Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Broder S (1988). "AIDS therapies.". Sci Am 259 (4): 110–9. PMID 3072667.

- ↑ Dr. Alan Howie. "Dr Alan Howie". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved on 2006-01-18.

- ↑ "Updated U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HIV". Retrieved on 2006-03-29.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health". Retrieved on 2006-03-29.

- ↑ Connor E, Sperling R, Gelber R, Kiselev P, Scott G, O'Sullivan M, VanDyke R, Bey M, Shearer W, Jacobson R (1994). "Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group.". N Engl J Med 331 (18): 1173–80. doi:. PMID 7935654.

- ↑ "ZIDOVUDINE (AZT) - ORAL (Retrovir) side effects, medical uses, and drug interactions". MedicineNet. Retrieved on 2006-01-09.

- ↑ Mitsuya H, Yarchoan R, Broder S (1990). "Molecular targets for AIDS therapy.". Science 249 (4976): 1533–44. doi:. PMID 1699273.

- ↑ Mitsuya H, Weinhold K, Furman P, St Clair M, Lehrman S, Gallo R, Bolognesi D, Barry D, Broder S (1985). "3'-Azido-3'-deoxythymidine (BW A509U): an antiviral agent that inhibits the infectivity and cytopathic effect of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus in vitro.". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82 (20): 7096–100. doi:. PMID 2413459. http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=2413459.

- ↑ Yarchoan R, Klecker R, Weinhold K, Markham P, Lyerly H, Durack D, Gelmann E, Lehrman S, Blum R, Barry D (1986). "Administration of 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, an inhibitor of HTLV-III/LAV replication, to patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex.". Lancet 1 (8481): 575–80. doi:. PMID 2869302.

- ↑ Furman P, Fyfe J, St Clair M, Weinhold K, Rideout J, Freeman G, Lehrman S, Bolognesi D, Broder S, Mitsuya H (1986). "Phosphorylation of 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine and selective interaction of the 5'-triphosphate with human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase.". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83 (21): 8333–7. doi:. PMID 2430286.

- ↑ Mitsuya H, Weinhold K, Furman P, St Clair M, Lehrman S, Gallo R, Bolognesi D, Barry D, Broder S (1985). "3'-Azido-3'-deoxythymidine (BW A509U): an antiviral agent that inhibits the infectivity and cytopathic effect of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus in vitro.". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82 (20): 7096–100. doi:. PMID 2413459.

- ↑ Plessinger M, Miller R (1999). "Effects of zidovudine (AZT) and dideoxyinosine (ddI) on human trophoblast cells.". Reprod Toxicol 13 (6): 537–46. doi:. PMID 10613402.

- ↑ Mitsuya H, Weinhold KJ, Furman PA, et al: 3'-azido-3;-deoxythymidine (BW A509U): an antiviral agent that inhibits the infectivity and cytopathic effect of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus in vitro. Med Sci 1985; 82:7096-7100.

- ↑ Collins M, Sondel N, Cesar D, Hellerstein M (2004). "Effect of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on mitochondrial DNA synthesis in rats and humans.". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 37 (1): 1132–9. doi:. PMID 15319672.

- ↑ Parker W, White E, Shaddix S, Ross L, Buckheit R, Germany J, Secrist J, Vince R, Shannon W (1991). "Mechanism of inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and human DNA polymerases alpha, beta, and gamma by the 5'-triphosphates of carbovir, 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, 2',3'-dideoxyguanosine and 3'-deoxythymidine. A novel RNA template for the evaluation of antiretroviral drugs.". J Biol Chem 266 (3): 1754–62. PMID 1703154.

- ↑ Rang H.P., Dale M.M., Ritter J.M. (1995). Pharmacology (3rd edition ed.). Pearson Professional Ltd.

- ↑ Balzarini J, Naesens L, Aquaro S, Knispel T, Perno C, De Clercq E, Meier C (1999). "Intracellular metabolism of CycloSaligenyl 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine monophosphate, a prodrug of 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine).". Mol Pharmacol 56 (6): 1354–61. PMID 10570065. http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/56/6/1354.

- ↑ Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Myers C, Broder S (1989). "Clinical pharmacology of 3'-azido-2',3'-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine) and related dideoxynucleosides.". N Engl J Med 321 (11): 726–38. PMID 2671731.

- ↑ The Best Democracy Money Can Buy by Greg Palast (2002)

- ↑ People with Aids Health Group v. Burroughs Wellcome Co., 1992 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 578

- ↑ US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. "Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Laboratories, 40 F.3d 1223 (Fed. Cir. 1994)". University of Houston -- Health Law and Policy Institute. Retrieved on 2007-02-28.

- Katzung, Bertram G. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 10th edition. New York: McGraw, Hill Lange Medical, 2007, pp.536-541

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||